Abstract

Background

Pulmonary paragonimiasis is a subacute to chronic inflammatory disease of the lung caused by lung flukes that result in prolonged inflammation and mechanical injury to the bronchi. However, there are few reports on the bronchoscopic findings of pulmonary paragonimiasis. This report describes the bronchoscopic findings of pulmonary paragonimiasis.

Methods

The bronchosocpic findings of 30 patients (20 males, median age 50 years) with pulmonary paragonimiasis between May 1995 and December 2007 were reviewed retrospectively.

Results

The diagnoses were based on a positive serologic test results for Paragonimus-specific antibodies in 13 patients (43%), or the detection of Paragonimus eggs in the sputum, bronchial washing fluid, or lung biopsy specimens in 17 patients (57%). The bronchoscopic examinations revealed endobronchial lesions in 17 patients (57%), which were located within the segmental bronchi in 10 patients (59%), lobar bronchi in 6 patients (35%) and main bronchi in 1 patient (6%). The bronchoscopic characteristics of endobronchial lesions were edematous swelling of the mucosa (16/17, 94%) and mucosal nodularity (4/17, 24%), accompanied by bronchial stenosis in 16 patients (94%). Paragonimus eggs were detected in the bronchial washing fluid of 9 out of the 17 patients with endobronchial lesions. The bronchial mucosal biopsy specimens showed evidence of chronic inflammation with eosinophilic infiltration in 6 out of 11 patients (55%). However, no adult fluke or ova were found in the bronchial tissue.

Pulmonary paragonimiasis is a food-borne parasitic disease of the lung caused by infection with Paragonimus westermani lung flukes, or other species in the genus Paragonimus1,2. Infection in humans occurs by ingestion of raw or incompletely cooked freshwater crab or crayfish infected with lung fluke metacercaria. These metacercariae pass through the intestinal wall, peritoneal cavity, diaphragm, and pleural cavity to finally enter the lung parenchyma, where they mature to adult flukes1,2. In a study of experimentally-induced pulmonary paragonimiasis, the juvenile worms tented and settled adjacent to the small airways, forming worm cysts1. These worm cysts commonly communicated with a bronchiole or bronchus, resulting in prolonged bronchial inflammation and mechanical injury to the airway3,4. Although bronchoscopy is not usually required to diagnose pulmonary paragonimiasis2, use of this technique has resulted in successful diagnosis on occasion3,4. However, few reports of the bronchoscopic findings of pulmonary paragonimiasis exist.

In South Korea, an area where P. westermani is endemic, although the incidence of the disease has recently decreased5,6, we have continued to observe clinical cases of pulmonary paragonimiasis with clinical features distinct from past cases3. Many of the patients in such cases underwent a bronchoscopy for the evaluation of hemoptysis or for a presumptive lung cancer work-up, as reported previously4,5. The purpose of this study was to describe the bronchoscopic findings of pulmonary paragonimiasis.

Thirty patients (20 males and 10 females, median age 50 years [interquartile range, IQR 45~59 years]) with pulmonary paragonimiasis who underwent bronchoscopy for airway evaluation at Samsung Medical Center, Seoul, Korea, between May 1995 and December 2007 were included. The clinical data of 13 out of 30 patients were included in an article published in 20053. Internal Review Board approval was obtained for the chart review, and informed consent was waived due to the retrospective nature of the study. The diagnoses were based on positive serologic test results for Paragonimus-specific antibody, or on the detection of characteristic Paragonimus eggs in sputum, bronchial washing, or lung biopsy specimens. Cytologic examinations were performed on sputum and bronchial washing fluid from all patients. The enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) test, an immunoserologic test for Paragonimus-specific IgG antibody, was performed on samples from 23 (77%) patients. Lung biopsies were performed in 18 (60%) patients. As a result, the diagnosis was confirmed serologically in 23 (77%) patients, histopathologically in 17 (57%) patients, or both. Ten (33%) patients had positive results for both ELISA test and the presence of Paragonimus eggs in cytologic or pathologic specimens.

Patient medical records were reviewed for clinical data including symptoms, history of eating raw or undercooked freshwater crab or crayfish, laboratory tests, and reasons for performing bronchoscopy. The bronchoscopic findings of all patients were reviewed. Characteristics such as the macroscopic description of mucosal changes (i.e., swelling, nodularity, and reddening) and the localization of the endobronchial lesions were recorded. Bronchial narrowing of at least 50% of the lumen was defined as stenosis. The location of endobronchial lesions was categorized as the main, lobar, or segmental bronchus. Abnormal findings of intrapulmonary parenchymal lesions in the chest radiographs were classified as airspace consolidation, nodular, linear, or cystic opacity.

The clinical and laboratory data of the patients are summarized in Table 1. Twenty-two (73%) patients presented with respiratory symptoms, including hemoptysis (n=19, 63%), cough (n=2, 7%), or dyspnea (n=1, 3%). Eight (27%) patients were asymptomatic, but the disease was discovered by abnormal chest radiography findings during general health examinations. Sixteen (53%) patients had a history of eating freshwater crustaceans, especially freshwater crabs pickled in soybean sauce (kejang) in Korea. Thirteen (43%) patients denied eating freshwater crustaceans. In the remaining patient (3%), no dietary history was available. Leukocytosis of the peripheral blood (>10,000/µL) was seen in one (3%) patient, while the WBC counts were within normal range in the remaining 29 patients (97%). Eosinophilia (>500/µL) was detected in the peripheral blood of 21 (70%) patients, and the degree of eosinophilia was median 10% (IQR 7~15%) in these 25 patients. Abnormal findings of intrapulmonary parenchymal lesions were observed in the chest radiographs, including nodular opacity in 17 (57%), airspace consolidation in 7 (23%), cystic opacity in 3 (10%), and linear infiltration in 3 (3%) patients.

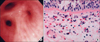

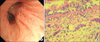

Flexible bronchoscopies were performed to evaluate hemoptysis in 19 patients (63%), for a presumptive lung cancer work-up in 9 patients (30%), and to evaluate endobronchial lesions on computed tomography in 2 (7%) patients. Bronchoscopic examinations revealed endobronchial lesions in 17 (57%) patients. The locations and appearance of endobronchial lesions are summarized in Table 2. The lesions were located within the segmental bronchi in 10 patients (59%), the lobar bronchi in 6 patients (35%), and the main bronchi in 1 patient (6%) The bronchial mucosa had a thickened, swollen, edematous appearance in 16 (94%) patients (Figure 1) and nodularity in 4 (24%) patients (Figure 2). Consequently, bronchial stenoses accompanied by mucosal changes were observed in 16 (94%) patients. Paragonimus eggs were detected in the bronchial washing fluid of 9 (53%) of 17 patients with mucosal changes on bronchoscopy. Bronchial mucosal biopsies were performed in 11 patients, and a pathologic specimen taken from the endobronchial lesion revealed chronic inflammation with eosinophilic infiltrations in six (55%) patients (Figures 1, 2). However, no adult fluke or ova were found in the bronchial tissue.

The objective of this retrospective study was to describe the bronchoscopic findings of pulmonary paragonimiasis. Endobronchial lesions were observed in 57% of patients with pulmonary paragonimiasis who had undergone bronchoscopy. The most common bronchoscopic finding was bronchial stenosis with mucosal changes. In half of the patients with endobronchial lesions, histopathologic abnormalities were also present.

In the pathogenesis of pulmonary paragonimiasis, human infection is acquired through ingestion of mertacercariae, the infective stage of the parasite. These metacercariae exist in the human duodenum and pass through the intestinal wall, peritoneal cavity, diaphragm, and pleural cavity to finally enter the lung parenchyma, where they mature to adult flukes2,7. They usually lodge near large bronchioles and bronchi, where the flukes deposit ova8. Im et al.9 reported that these lung flukes tent and settle adjacent to the small airways based on radiographic findings from 78 patients with pulmonary paragonimiasis. Furthermore, prolonged bronchial inflammation and mechanical injury of the airway by intrabronchial flukes have been observed in a study of experimentally-induced pulmonary paragonimiasis10. Therefore, inflammation of the bronchi by lung flukes may contribute to the development of mucosal changes with or without stenosis at the injured bronchi3,4.

Only a few reports have characterized endobronchial lesions in patients with pulmonary paragonimiasis. Mukae et al.4 reported bronchial stenosis in seven of nine patients (78%) who had undergone bronchoscopy. We observed bronchial stenosis with mucosal changes in 16 (53%) of 30 patients, consistent with the results of the previous study. In addition, chronic inflammation with eosinophilic infiltration was observed in 6 (55%) of 11 patients. Therefore, our results, combined with those of previous studies1,4, indicate that Paragonimus infection results in inflammation of the bronchi culminating in bronchial stenosis accompanied by mucosal changes.

Diagnosis of pulmonary paragonimiasis can be readily established in patients with typical symptoms by identifying parasite eggs in the sputum or using ELISA to detect parasite-specific IgG antibodies2. However, the diagnosis of pulmonary paragonimiasis can be challenging in patients who are asymptomatic, middle-aged, and have nodular or mass lesions on chest radiographs11,12. Therefore, bronchoscopy may be required to differentiate pulmonary paragonimiasis from other pulmonary diseases such as lung cancer or tuberculosis3,4. Only a few studies have investigated the validity of using bronchoscopy to diagnose pulmonary paragonimiasis. Mukae et al.4 reported that cytologic examination of bronchial brushing or fluid is useful for the diagnosis of pulmonary paragonimiasis. We detected Paragonimus eggs on cytologic examination of bronchial washing fluid in 53% of patients with endobronchial lesions on bronchoscopy. In addition, bronchial mucosal biopsy specimens showed evidence of chronic inflammation with eosinophilic infiltration in 55% of patients, even though no parasites or eggs were found in specimens from these patients. Therefore, a bronchoscopic examination could be useful for the diagnosis of pulmonary paragonimiasis, especially in patients who are asymptomatic, middle-aged, and have nodular or mass lesions on chest radiographs.

In conclusion, the most common bronchoscopic finding of pulmonary paragonimiasis is bronchial stenosis with mucosal changes. In such patients, a bronchial washing or biopsy may be useful for the diagnosis of pulmonary paragonimiasis.

Figures and Tables

| Figure 1Bronchoscopic appearance and histologic findings of bronchial mucosal biopsy specimens in a 44-year-old male with pulmonary paragonimiasis. (A) Fiberoptic bronchoscopy revealed bronchial stenosis that was associated with mucosal edema of the posterior segmental bronchus of the right upper lobe. (B) Photomicrograph of bronchial tissue obtained from the posterior segmental bronchus of the right upper lobe showing thickening of the basement membrane, chronic inflammation with eosinophilic infiltration, and multinucleated giant cell formation (H&E stain, ×400). |

| Figure 2Bronchoscopic appearance and histologic findings of bronchial mucosal biopsy specimens in a 55-year-old female with pulmonary paragonimiasis. (A) Fiberoptic bronchoscopy revealed mucoal nodularity on the right upper lobe. (B) Photomicrograph of bronchial tissue obtained from the right upper lobar bronchus showing thickening of the basement membrane, chronic inflammation with eosinophilic infiltration, and the presence of several multinucleated giant cells (H&E stain, ×200). |

References

1. Im JG, Kong Y, Shin YM, Yang SO, Song JG, Han MC, et al. Pulmonary paragonimiasis: clinical and experimental studies. Radiographics. 1993. 13:575–586.

2. Kagawa FT. Pulmonary paragonimiasis. Semin Respir Infect. 1997. 12:149–158.

3. Jeon K, Koh WJ, Kim H, Kwon OJ, Kim TS, Lee KS, et al. Clinical features of recently diagnosed pulmonary paragonimiasis in Korea. Chest. 2005. 128:1423–1430.

4. Mukae H, Taniguchi H, Matsumoto N, Iiboshi H, Ashitani J, Matsukura S, et al. Clinicoradiologic features of pleuropulmonary Paragonimus westermani on Kyusyu Island, Japan. Chest. 2001. 120:514–520.

5. Choi DW. Paragonimus and paragonimiasis in Korea. Korean J Parasitol. 1990. 28:Suppl. 79–102.

6. Cho SY, Kong Y, Kang SY. Epidemiology of paragonimiasis in Korea. Southeast Asian J Trop Med Public Health. 1997. 28:Suppl 1. 32–36.

7. Yokogawa M. Paragonimus and paragonimiasis. Adv Parasitol. 1969. 7:375–387.

8. Rangdaeng S, Alpert LC, Khiyami A, Cottingham K, Ramzy I. Pulmonary paragonimiasis: report of a case with diagnosis by fine needle aspiration cytology. Acta Cytol. 1992. 36:31–36.

9. Im JG, Whang HY, Kim WS, Han MC, Shim YS, Cho SY. Pleuropulmonary paragonimiasis: radiologic findings in 71 patients. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 1992. 159:39–43.

10. Diaconita G, Goldis G. Pathomorphology and pathogenesis of pulmonary paragonimiasis. Acta Morphol Acad Sci Hung. 1964. 12:315–331.

11. Yoshino I, Nawa Y, Yano T, Ichinose Y. Paragonimiasis westermani presenting as an asymptomatic nodular lesion in the lung: report of a case. Surg Today. 1998. 28:108–110.

12. Tomita M, Matsuzaki Y, Nawa Y, Onitsuka T. Pulmonary paragonimiasis referred to the department of surgery. Ann Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2000. 6:295–298.

PDF

PDF ePub

ePub Citation

Citation Print

Print

XML Download

XML Download