Abstract

Erdheim-Chester disease (ECD) is a proliferative non-Langerhans cell histiocytosis of multiple organs. This is a rare disease of unknown etiology with a high mortality. We present the case report of a 26-year-old man diagnosed with ECD. He was referred to our hospital with elevated levels of aminotransferases. Although the diagnosis was uncertain, the patient was lost to follow up at that time. One year later, the patient returned to the hospital with generalized edema. Although a specific bone lesion was not found, the patient was experiencing the following: glomerulonephritis, aplastic anemia, hepatitis, and lung involvement. A lung biopsy was performed: the immunohistochemical stain were positive for CD68 and negative for S-100 protein and CD1a. We diagnosed as the patient as havinf ECD. Approximately 50% of ECD cases present with extraskeletal involvement. ECD should be considered as part of the differential diagnosis when multiple organs are involved.

Erdheim-Chester disease (ECD) is a rare disease with distinct clinicopathologic and radiographic features and unknown etiology. In 1930, William Chester and his mentor, the Viennese pathologist Erdheim first described two patients with a distinctive form of lipoid granulomatosis that they regarded as different from other histiocytic disorders, particularly Hand-Schuller-Christian and Niemann-Pick diseases1,2.

In 1972, Jaffe reported a similar case and named this disease after Erdheim and Chester. ECD is caused by xanthogranulomatous infiltration of numerous foamy non-Langerhans' cell, lipid-laden histiocytes. It has nearly diagnostic radiological changes characterized by bilateral osteosclerosis that involves the long bone metaphyses and diaphyses symmetrically but spares the epiphyses3-5.

The most common sites involved are the distal femur, proximal tibia and fibula5. The clinical spectrum ranges from focal bone lesions to multisystemic, life threatening involvement of the visceral organs. The disease may also affect the central nervous system, heart, pericardium, lungs, kidney, retroperitoneal and retro-orbital tissue. The disease is classically described as presenting in middle age (mean age of 53 years) with bone pain from generalized involvement of the long bones and affecting males over the age of 40. As there is no established treatment, ECD has a mortality rate of 60%. Pulmonary involvement is uncommon in ECD but the prognosis is grave and the treatment is difficult6. We describe a case of ECD that had hepatitis, glomerulonephritis, aplastic anemia and pulmonary involvement.

A 26-year-old Korean man was referred to Chungnam national university hospistal in February 2005 with elevated Aspartate Aminotransferase (AST) and Alanine Aminotransferase (ALT). The value was 192 IU/mL and 202 IU/mL. He had nonspecific symptoms and signs. Hepatitis B core Antibody (Ab), hepatitis A Ab, hepatitis B surface antigen and Ab, anti HCV, antinuclear Ab, anti smooth muscle Ab and anti mitochondria Ab were negative. Liver and gallbladder sonography finding was nonspecific.

After one more visit, he did not visit the hospital.

January 2006, he presented with general edema especially face, both legs for 3 months. Physical examination showed pretibial pitting edema and coarse crackles in the lungs. Urinalysis showed proteinuria 3+, many RBC per high power field. BUN and creatinine were within normal limit. AST and ALT were 127 IU/mL and 91 IU/mL respectively. Kidney sonographic image was nonspecific and kidney biopsy showed diffuse thickening of capillary wall with focal endocapillary proliferation. Some tufts are segmentally sclerotic or show segmental hyalinosis. Ultrastuctural finding showed diffuse endocapillary proliferation, associated with mesangial and subendothelial electron-dense deposits. The glomerular basement membranes are normal thickness, but occasionally thickened (Figure 1).

Liver biopsy showed chronic hepatitis with mild lobular activity, mild porto-periportal activity and periportal fibrosis (Figure 2). His body weight decreased from 68 kg to 65 kg and generalized edema improved with diuretics. He discharged and planned to visit nephrology and hepatology departments.

His complete blood count (CBC) was within normal limit at January 2006 but CBC was abnoraml at follow up labaratory data. March 2007, hemoglobin, white blood cell, absolute neutrophil count and platelet counts were 9.7 g/dL, 1,770/mm3, 1,000/mm3 and 112,000/mm3 respectively. Bone marrow aspiration was performed and the result showed cellularity was less than 5%, aplastic anemia. CBC was checked regularly and there were no specific changes.

October 2007, he complained of generalized edema and dyspnea on exercise. Chest radiology showed multifocal nodular consolidation with air bronchogram and multifocal patchy ground glass opacity on mainly both lower lobe, right middle lobe, lingular division and associated subtle prominent interlobular septal thickening (Figure 3). Pulmonary function testing showed moderate restrictive pattern with forced expiratory volume at one second (FEV1) of 2.25 L (54% predicted), FEV1/forced vital capacity (FVC) of 73%. Echocardiography showed concentric left ventricular hypertrophy and moderate resting pulmonary hypertension.

Liver scan showed severe hepatic dysfunction, huge hepatosplenomegaly. Abdominal sonography showed hepatosplenomegaly, large amount of ascites.

He did not complaint of bone pain. Although bone scan showed increased radionuclide uptake to the whole bones, skeletal radiography showed no sclerotic or mixed sclerotic/lytic lesions of the metaphyseal and diaphyseal regions.

Treatment was started with antibiotics and diuretics but the patient deteriorated clinically and chest radiology showed progressive bilateral interstitial marking. The cause of general edema and interstitial lung disease remained unknown and open lung biopsy was performed.

Open lung biopsy from right middle lobe showed pleural and perivascular histiocytic infiltration (Figure 4). The Immunohistochemical stains showed positive for CD68 and negative for S-100 protein and CD1a (Figure 5). Those means the histiocyte were not originated from the Largerhans cell. We diagnosed him as ECD.

At that time he was treated with steroid pulse therapy (methylprednisolone, 1 g/day for 3 days). He was given prednisolone (60 mg/day) and cyclophosphamide (100 mg/day) after steroid pulse therapy.

But his general condition did not improved. We managed him with mechanical ventilatory support. On day 38 from admission, he died of repiratory failure due to progression of interstitial lung disease.

ECD is a very rare, non-Langerhans cell histiocytic, infiltrative disorder that primarily involves bone marrow and multiple other organ systems.

Histologically, ECD differs from Langerhans cell histiocytosis (LCH) in a number of ways. Unlike LCH, ECD does not stain positive for S-100 or CD-1a, and electron microscopy of cell cytoplasm does not disclose Birbeck granules. Tissue samples show xanthomatous or xanthogranulomatous infiltration by lipid-laden or foamy histiocytes, and are usually surrounded by fibrosis1.

Although Langerhans cell histiocytosis is generally a childhood disease, ECD affects adults in the fourth and fifth decades of life and has a male predominance2.

Bone pain is the most common initial clinical symptom. The histiocytic process begins in the skeletal system, primarily affecting the long bones of the appendicular skeleton. Bilateral and symmetrical cortical osteosclerosis of the metaphyses and diaphyses of the long bones with sparing of the epiphyses is pathognomonic for ECD5.

Our case had no bone problem. There are typical radiographical and pathological features, which can lead to the diagnosis, but the clinical spectrum shows a broad variation. In one article, the skeleton is involved in 70~80% of all cases7. And in their review of 59 reported cases by Veyssier-Belot et al8 that suggested that ECD, 10 case were not reported the bone involvement. The absence of defined criteria for the diagnosis of ECD is a factor contributing to this controversy. Although our patient lacked the most frequently occurring involovment of bone, the result of immunohistochemical stain and multiple organ manifestation were compatible with ECD.

ECD affects numerous organ systems with neurologic, orbital, pulmonary, cardiova- scular, lymphatic, and renal manifestations9-12.

Pulmonary and renal impairments often contribute to the death of patients with ECD. Dyspnea is the most common pulmonary symptom and infiltration of the interstitial spaces and the pleura can be seen on chest CT. Chest CT finding of ECD is nonspecific but usually has diffuse thickening of interlobular septal line and peribronchial fibrosis, centrilobular opacity and glass ground opacity (Table 1)2-6,13. CT findings of our patient coincide with other case reports. Histological changes in the lungs include infiltration of lipid-laden macrophages and granulomatous lesions with fibrosis13,14.

The prognosis for survival is usually poor and dependent on the extent of visceral involvement. Unfortunately, treatment strategies have been limited to attempts at combining immunosuppression and chemotherapy. The delay in the diagnosis may have in some way constributed to his unfortuneate outcome. But some case reports informed that patients improved after corticosteroid or cyclophosphamide therapy5,15.

In our case, he was diagnosed to late stage of interstitial lung disease due to ECD by open lung biopsy and he also had history of hepatitis, glomerulonephritis and aplastic anemia. Our patient had extensive organ involvement with characteristic histological features (mononuclear infiltrate consisting of lipid laden, foamy histiocytes that stain positive for CD68) but the typical skeletal complaints were lacking.

In the patient with extensive organ involvement, clinician should be aware of ECD and a histological and immunohistochemical examination is crucial for the diagnosis of ECD.

Figures and Tables

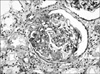

Figure 1

Kidney biopsy of the patient show diffuse thickening of capillary wall with focal endocapillary proliferation (H&E stain, ×400).

Figure 2

Liver biopsy of the patient show chronic hepatitis with mild lobular activity, mild porto-periportal activity and periportal fibrosis (Masson's trichrome stain, ×400).

Figure 3

Chest PA on hospital day and Chest HRCT of the patient. Chest radiology show multifocal nodular consolidation and patchy ground glass opacity with air bronchogram and interlobular septal thickening.

Figure 4

Lung biopsy of the patient show expansion of visceral pleura. And microscopic finding demonstrates aggregation of histiocytes and fibrosis in interlobular septa and perivascular area (H&E stain, ×100).

References

1. Furmanczyk PS, Bruckner JD, Gillespy T 3rd, Rubin BP. An unusual case of Erdheim-Chester disease with features of Langerhans cell histiocytosis. Skeletal Radiol. 2007. 36:885–889.

2. Chung JH, Park MS, Shin DH, Choe KO, Kim SK, Chang J, et al. Pulmonary involvement in Erdheim-Chester disease. Respirology. 2005. 10:389–392.

3. Adem C, Hélie O, Lévêque C, Taillia H, Cordoliani YS. Case 78: Erdheim-Chester disease with central nervous system involvement. Radiology. 2005. 234:111–115.

4. Al-Quran S, Reith J, Bradley J, Rimsza L. Erdheim-Chester disease: case report, PCR-based analysis of clonality, and review of literature. Mod Pathol. 2002. 15:666–672.

5. Matsui K, Nagata Y, Hiraoka M. Radiotherapy for Erdheim-Chester disease. Int J Clin Oncol. 2007. 12:238–241.

6. Krüger S, Krop C, Wibmer T, Pauls S, Mottaghy FM, Schumann C, et al. Erdheim-chester disease: a rare cause of interstitial lung disease. Med Klin (Munich). 2006. 101:573–576.

7. Spyridonidis TJ, Giannakenas C, Barla P, Apostolopoulos DJ. Erdheim-Chester disease: a rare syndrome with a characteristic bone scintigraphy pattern. Ann Nucl Med. 2008. 22:323–326.

8. Veyssier-Belot C, Cacoub P, Caparros-Lefebvre D, Wechsler J, Brun B, Remy M, et al. Erdheim-Chester disease: clinical and radiologic characteristics of 59 cases. Medicine (Baltimore). 1996. 75:157–169.

9. Lau WW, Chan E, Chan CW. Orbital involvement in Erdheim-Chester disease. Hong Kong Med J. 2007. 13:238–240.

10. Garg T, Chander R, Gupta T, Mendiratta V, Jain M. Erdheim-Chester disease with cutaneous features in an Indian patient. Skinmed. 2008. 7:103–106.

11. Loddenkemper K, Hoyer B, Loddenkemper C, Hermann KG, Rogalla P, Förster G, et al. A case of Erdheim-Chester disease initially mistaken for Ormond's disease. Nat Clin Pract Rheumatol. 2008. 4:50–55.

12. Dinkar AD, Spadigam A, Sahai S. Oral radiographic and clinico-pathologic presentation of Erdheim-Chester disease: a case report. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod. 2007. 103:e79–e85.

13. Egan AJ, Boardman LA, Tazelaar HD, Swensen SJ, Jett JR, Yousem SA, et al. Erdheim-Chester disease: clinical, radiologic, and histopathologic findings in five patients with interstitial lung disease. Am J Surg Pathol. 1999. 23:17–26.

14. Dickson BC, Pethe V, Chung CT, Howarth DJ, Bilbao JM, Fornasier VL, et al. Systemic Erdheim-Chester disease. Virchows Arch. 2008. 452:221–227.

15. Yano S, Kobayashi K, Kato K, Tokuda Y, Ikeda T, Takeyama H. A case of Erdheim-Chester disease effectively treated by cyclophosphamide and prednisolone. Nihon Kokyuki Gakkai Zasshi. 2007. 45:43–48.

PDF

PDF ePub

ePub Citation

Citation Print

Print

XML Download

XML Download