Abstract

Background

Although the prevalence of tuberculosis infections (PTBI) is one of the basic epidemiologic indices, no survey has been carried out since 1995 because the nation-wide tuberculosis prevalence survey was changed to a surveillance system. Subjects without a BCG scar are examined in a tuberculin survey. However, it is very difficult to select these subjects under high vaccination coverage. It is important to evaluate the impact of BCG vaccinations on the tuberculin response and estimate the PTBI regardless of the BCG vaccination status.

Methods

A nation-wide, school-based cross-sectional tuberculin survey was carried out among first graders in elementary school in 2006. A total of 5,148 children in 40 schools were selected by quota sampling. Tuberculin testing with 0.1 ml of two tuberculin units of PPD RT23 was carried out on 4,018 children. The maximum transverse diameter of induration was measured 48 to 72 hours later. The presence of a BCG scar was checked separately.

Results

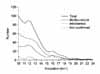

There were no BCG scars in 6.3% of the subjects. The mean induration size of tuberculin testing was 3.7±4.4 mm, which included 1,882 (46.8%) subjects with an induration size of 0 mm. The PTBI was 10.9% (439 subjects) using a cut-off point of ≥10 mm (conventional method). The annual risk of tuberculosis infections (ARTI) was 1.9% when the mean age of the subjects was assumed to be 6 years. There was no difference in the PTBI according to the presence or absence of a BCG scar [11.2% vs 7.6% (OR: 1.54, 95% CI: 0.98~2.43)]. Using a mirror image technique with 16 mm as the cut-off point, the PTBI and ARTI had decreased to 2.4% and 0.4% respectively.

Figures and Tables

References

1. Bleiker MA. The annual tuberculosis infection rate, the tuberculin survey and the tuberculin test. Bull Int Union Tuberc Lung Dis. 1991. 66:53–56.

2. Farhat M, Greenaway C, Pai M, Menzies D. False-positive tuberculin skin tests: what is the absolute effect of BCG and non-tuberculous mycobacteria? Int J Tuberc Lung Dis. 2006. 10:1192–1204.

3. The Ministry of Health and Welfare, The Korean National Tuberculosis Association. Report on the 7th National tuberculosis prevalence survey. 1996. Seoul, Republic of Korea: The Korean National Tuberculosis Association.

4. Gopi PG, Subramani R, Nataraj T, Narayanan PR. Impact of BCG vaccination on tuberculin surveys to estimate the annual risk of tuberculosis infection in south India. Indian J Med Res. 2006. 124:71–76.

5. American Thoracic Society. Tuberculin skin test. Am Rev Respir Dis. 1981. 124:356–363.

6. Leung CC, Yew WW, Tam CM, Chan CK, Chang KC, Law WS, et al. Tuberculin response in BCG vaccinated schoolchildren and the estimation of annual risk of infection in Hong Kong. Thorax. 2005. 60:124–129.

7. Arnadottir T, Rieder HL, Trébucq A, Waaler HT. Guidelines for conducting tuberculin skin test surveys in high prevalence countries. Tuber Lung Dis. 1996. 77:Suppl 1. 1–19.

8. Menzies D. What does tuberculin reactivity after bacille Calmette-Guén vaccination tell us? Clin Infect Dis. 2000. 31:S71–S74.

9. Chadha VK, Jagannatha PS, Kumar P. Can BCG-vaccinated children be included in tuberculin surveys to estimate the annual risk of tuberculous infection in India? Int J Tuberc Lung Dis. 2004. 8:1437–1442.

10. Al-Jahdali H, Memish ZA, Menzies D. The utility and interpretation of tuberculin skin tests in the Middle East. Am J Infect Control. 2005. 33:151–156.

11. Smeja C, Brassard P. Tuberculosis infection in an Aboriginal (First Nations) population of Canada. Int J Tuberc Lung Dis. 2000. 4:925–930.

12. Wang L, Turner MO, Elwood RK, Schulzer M, FitzGerald JM. A meta-analysis of the effect of Bacille Calmette Guerin vaccination on tuberculin skin test measurements. Thorax. 2002. 57:804–809.

13. The Ministry of Health and Social Affairs, The Korean National Tuberculosis Association. Report on the 6th National tuberculosis prevalence survey. 1991. Seoul, Republic of Korea: The Korean National Tuberculosis Association.

14. Gopi PG, Subramani R, Santha T, Kumaran PP, Kumaraswami V, Narayanan PR. Relationship of ARTI to incidence and prevalence of tuberculosis in a district of south India. Int J Tuberc Lung Dis. 2006. 10:115–117.

15. Harada N. Characteristics of a diagnostic method of tuberculosis infection based on whole blood interferon-gamma assay. Kekkaku. 2006. 81:681–686.

PDF

PDF ePub

ePub Citation

Citation Print

Print

XML Download

XML Download