Tuberculosis is a contagious bacterial disease that primarily involves the lungs and infrequently, intense systemic dissemination from the rupture of a Mycobacterium tuberculosis-laden focus into a vascular channel results in miliary tuberculosis.

Miliary tuberculosis accounts for about 1-2% of all cases of tuberculosis and about 8% of all forms of extrapulmonary tuberculosis in immunocompetent individuals1,2. It usually occurs in HIV infection, malignancy, immunosuppressive therapy, chronic renal failure, malnutrition, and chronic alcoholism3.

We observed an unusual form of miliary tuberculosis who presented with multiorgan involvement including liver, spleen, kidney, meninges, and brain in immunocompetent patient.

An 18-year old girl was admitted to the hospital because of 2 weeks history of dry cough, fever, and headache. She was a healthy high school student and went on a fast 2 months ago. Clinical examination revealed a obese, slightly tachypneic patient with blood pressure of 110/70 mm Hg, temperature of 37.3℃, heart rate of 104 beats/min, and respiratory rate of 26 breaths/min. She appeared ill but examination of the lung and heart was unremarkable. Abdominal examination revealed tenderness in right upper region without hepatosplenomegaly and left costovertebral tenderness. She also had neck stiffness upon neck flexion.

Laboratory data revealed the following: WBC count, 10,230/mm3 with neutrophil, 87% and lymphocyte, 9%; hemoglobin, 12.7 g/dl; hematocrit 36.8%; albumin, 3.7 g/dl; AST, 48 IU/L; ALT, 51 IU/L; alkaline phosphatase 157 IU/L; total bilirubin, 2.3 mg/dl with direct bilirubin, 1.1 mg/dl. A urinalysis showed 2 + protein, 0 to 1 RBCs, and 2 to 3 WBCs per high-power field. Arterial blood gas analysis showed a pH of 7.51; PaCO2, 27.4 mm Hg; PaO2, 74.4 mm Hg; and oxygen saturation, 96.4% while she was breathing ambient air. Tuberculin skin test and HIV serology were negative. Fundus examination was unremarkable.

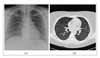

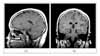

Chest X ray (Figure 1A) and high-resolution thorax computed tomography (Figure 1B) were interpreted as a positive evidence for miliary tuberculosis. Abdominal CT (Figure 2) showed multiorgan involvement including liver, spleen, and kidney: ill defined enhancing lesion in liver; a peripheral wedge shaped low attenuation in upper area of spleen; an ill defined low attenuation in lower area of left kidney. Magnetic resonance imaging (Figure 3) of brain revealed multiple small enhancing nodules in cerebral hemispheres, right cerebellar hemisphere, left basal ganglia, brain stem, and letomeningeal enhancement of right parietal lone.

A lumbar puncture was performed. Cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) examination showed 300 WBC/mm3 with 80% neutrophils and 20% lymphocytes, protein 57 mg/dl, glucose 41 mg/dl, and raised ADA level 9 IU/L. Sputum, CSF, and urine smears for Mycobacteria were negative. Her parent refused to have invasive biopsy procedure.

The patient was promptly started empirically on antituberculous therapy, with isoniazid, rifampin, ethambutol, pyrazinamide and combined with dexamethasone tapered over six weeks for meningitis. At a 2-month follow up, she had improved with gradual resolution of constitutional symptoms and fine infiltrations on chest radiography. Culture of sputum, CSF, and blood were negative for Mycobacterium tuberculosis. But Mycobacterium tuberculosis was isolated only in a urine culture.

At 5 months after antituberculous treatment she was well. Repeated abdomen CT revealed resolution of previous abnormal findings in liver, but an increase in the size of spleen with multiple hypoattenuating lesions of spleen and both kidney. Follow up Brain MRI also showed aggravating nodules in frontotemporal area with improving of previous nodules in cerebral and cerebellar hemisphere. She was referred to another teaching hospital for further evaluation. US-guided aspiration of spleen was then performed instead of more invasive brain biopsy. Histological result was characterized by caseating granulomatous inflammation consistent with tuberculosis. She continued to improve on the same antituberculous treatment, which was stopped after 12 months.

Miliary tuberculosis is a potentially lethal form of tuberculosis resulting from massive hematogenous dissemination of Mycobacterium tuberculosis bacilli. At autopsy, organs with high blood flow are frequently affected in miliary tuberculosis: spleen, liver, lungs, bone marrow, kidneys, and adrenals.

Clinical manifestations of miliary tuberculosis are nonspecific and protean, depending on the predominant site of involvement. Fever, night sweats, anorexia, weakness, and weight loss are presenting symptoms in the majority of cases. At times, patients have a cough and other respiratory symptoms due to pulmonary involvement as well as abdominal symptoms. Physical findings include hepatomegaly, splenomegaly, and lymphadenopathy.

Hepatic granulomas are present in more than 90 percent of patients with miliary tuberculosis, approximately 70 percent of those with extrapulmonary tuberculosis4. Serum aminotransferases may be minimally elevated and jaundice is rare. Splenic involvement is very rare and is usually associated with miliary dissemination, and involvement of the liver is quite frequent5,6. CT image of splenic tuberculosis usually demonstrates small multiple hypoattenuating lesions and splenomegaly7. Final diagnosis was made by laparotomy, although CT guided splenic puncture is becoming a more ideal and popular method nowadays8.

Tuberculosis of the urinary tract is easily overlooked. Suspicions of tuberculosis are aroused only when there is no response to the usual antibacterial agents or when urine examination reveals pyuria in the absence of a positive culture on routine media9. The kidney is frequently involved in miliary tuberculosis where blood-borne miliary tubercles are seen throughout the renal substance, most noticeably in the cortex. Organisms can be usually demonstrated microscopically within these lesions but sometimes are difficult to find. Renal function is not usually compromised in these patients9.

Central nervous system(CNS) disease such as meningitis or tuberculoma is suggested clinically in 15 to 20 percent of patients10. In a study, all 20 patients with miliary tuberculosis had meningitis and on MRI 7 patients had miliary tuberculoma11. The prognosis of miliary tuberculosis is linked to age, immune status and multiorgan involvement but CNS involvement has been reported as an independent predictor of mortality.

Treatment guidelines state that 6 months of treatment adequate in miliary tuberculosis12. In the presence of associated tuberculosis meningitis, treatment needs to be given for at least 12 months12. Adjunctive corticosteroid treatment may be beneficial in miliary tuberculosis with tuberculosis meningitis, large pericardial or pleural effusion13.

On follow up abdominal CT and brain MRI in the presented case, aggravating findings of spleen, kidney, and brain lesion were thought to be a transient paradoxical worsening of tuberculosis. Discussion concerning the mechanism of this entity is still controversial. The most likely explanation is interplay between the host's immune responses and the direct effects of mycobacterial products14. Antituberculous drugs cause destruction of mycobacterial structures and liberation of bacillary proteins that provoke a delayed hypersensitivity immune reaction. In accordance with the previously reported cases in literature, we also believe in that CNS tuberculoma enlargement does not necessitate changes in the administered antituberculous drugs, but requires prolonged treatment15.

Figures and Tables

| Figure 1(A) Chest Radiograph shows fine nodular opacites bilaterally. (B) High Resolution CT shows numerous fine and discrete nodules bilaterally in a random distribution. |

References

1. Rieder HL, Snider DE Jr, Cauthen GM. Extrapulmonary tuberculosis in the United States. Am Rev Respir Dis. 1990. 141:347–351.

2. Long R, O'Connor R, Palayew M, Hershfield E, Manfreda J. Disseminated tuberculosis with and without a miliary pattern on chest radiograph: a clinical-pathologic-radiologic correlation. Int J Tuberc Lung Dis. 1997. 1:52–58.

3. Hill AR, Premkumar S, Brustein S, Vaidya K, Powell S, Li PW, et al. Disseminated tuberculosis in the acquired immunodeficiency syndrome era. Am Rev Respir Dis. 1991. 144:1164–1170.

4. Klatskin G. Hepatic granulomata: problems in interpretation. Mt Sinai J Med. 1977. 44:798–812.

5. Jain A, Sharma AK, Kar P, Chaturvedi KU. Isolated splenic tuberculosis. J Assoc Physicians India. 1993. 41:605–606.

6. Gulati MS, Sarma D, Paul SB. CT appearances in abdominal tuberculosis. A pictorial essay. Clin Imaging. 1999. 23:51–59.

7. Radin DR. Intraabdominal Mycobacterium tuberculosis vs Mycobacterium avium-intracellulare infections in patients with AIDS: distinction based on CT findings. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 1991. 156:487–491.

8. Adil A, Chikhaoui N, Ousehal A, Kadiri R. Splenic tuberculosis. Apropos of 12 cases. Ann Radiol (Paris). 1995. 38:403–407.

9. Eastwood JB, Corbishley CM, Grange JM. Tuberculosis and the kidney. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2001. 12:1307–1314.

10. Maartens G, Willcox PA, Benatar SR. Miliary tuberculosis: rapid diagnosis, hematologic abnormalities, and outcome in 109 treated adults. Am J Med. 1990. 89:291–296.

11. Kalita J, Misra UK, Ranjan P. Tuberculous meningitis with pulmonary miliary tuberculosis: a clinicoradiological study. Neurol India. 2004. 52:194–196.

12. Blumberg HM, Burman WJ, Chaisson RE, Daley CL, Etkind SC, Friedman LN, et al. American Thoracic Society/Centers for Disease Control and Prevention/Infectious Diseases Society of America: treatment of tuberculosis. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2003. 167:603–662.

13. Baker SK, Glassroth J. Rom WN, Garay SM, editors. Miliary tuberculosis. Tuberculosis. 2004. Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins;427–444.

14. Afghani B, Lieberman JM. Paradoxical enlargement or development of intracranial tuberculomas during therapy: case report and review. Clin Infec Dis. 1994. 19:1092–1099.

15. Hejazi N, Hassler W. Multiple intracranial tuberculomas with atypical response to tuberculostatic chemotheraphy: literature review and a case report. Infection. 1997. 25:233–239.

PDF

PDF ePub

ePub Citation

Citation Print

Print

XML Download

XML Download