Abstract

Background

Although airway hyper-responsiveness is one of the characteristics of asthma. bronchial hyper-responsiveness has also been observed to some degree in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD). Moreover, several reports have demonstrated that a number of patients have both COPD and asthma. The methacholine bronchial challenge test (MCT) is a widely used method for the detecting and quantifying the airway hyper-responsiveness, and is one of the diagnostic tools in asthma. However, the significance of MCT in differentiating asthma or COPD combined with asthma from pure COPD has not been defined. The aim of this study was to determine the role of MCT in differentiating asthma from pure COPD.

Method

This study was performed prospectively and was composed of one hundred eleven patients who had undergone MCT at Chonbuk National University Hospital. Sixty-five asthma patients and 23 COPD patients were enrolled and their MCT data were analyzed and compared with the results of a control group.

Result

The positive rates of MCT were 65%, 30%, and 9% in the asthma, COPD, and control groups, respectively. The mean PC20 values of the asthma, COPD, and control groups were 8.1±1.16 mg/mL, 16.9±2.21 mg/mL, and 22.0±1.47 mg/mL, respectively. The sensitivity, specificity, positive predictive value, and negative predictive value of MCT for diagnosing asthma were 65%, 84%, 81%, and 69%, respectively. The sensitivity, specificity, positive predictive value, and negative predictive value of MCT (ed note: please check this as I believe that these values correspond to the one PC20 value. Please check my changes.) at the new cut-off points of PC20 ≤ 16 mg/ml, were 80%, 75%, 78%, and 78%, respectively.

Figures and Tables

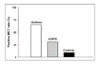

| Figure 1Positive rates of MCT in subjects with asthma or COPD and in control group. MCT positive rate of the asthma, COPD, and contol group were 65%, 30%, and 9%, respectively. |

| Figure 2PC20 values in subjects with asthma or COPD and in control group. Each solid black bar indicates mean value of each group. |

| Figure 3Mean values of PC20 in subjects with asthma or COPD and in control group. The mean value of asthma, 8.1±1.2 mg/ml, is lower than others significantly (P<0.05). |

| Figure 5The differences of sensitivity, specificity, negative predictive value, and positive predictive of MCT for diagnosis of asthama at different cut-off point, PC20≤16 mg/ml, from usual cut-off value, PC20≤8.0 mg/mL. |

References

1. National Collaborating Centre for Chronic Conditions. National clinical guideline on management of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease in adult in primary and secondary care. Thorax. 2004. 59:Suppl. 1–232.

2. Grootendorst DC, Rabe KF. Mecahnisms of bronchial hyperreactivity in asthmaand chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Proc Am Thorac Soc. 2004. 1:77–87.

3. Burney PG, Britton JR, Chinn S, Tattersfield AE, Papacosta AO, Kelson MC, et al. Descriptive epidemiology of bronchial reactivity in an adult population: results from a community study. Thorax. 1987. 42:38–44.

4. Britton J, Pavord I, Richards K, Knox A, Wisniewski A, Wahedna I, et al. Factors influencing the occurrence of airway hyperreactivity in the general population: the importance of atopy and airway caliber. Eur Respir J. 1994. 7:881–887.

5. Woolcock AJ, Peat JK, Salome CM, Yan K, Anderson SD, Schoeffel RE, et al. Prevalence of bronchial hyperresponsiveness and asthma in a rural adult population. Thorax. 1987. 42:361–368.

6. Ernst P, Ghezzo H, Becklake MR. Risk factors for bronchial hyperresponsiveness in late childhood and early adolescence. Eur Respir J. 2002. 20:635–639.

7. Trigg CJ, Manolitsas ND, Wang J, Calderon MA, McAuley A, Jordan SE, et al. Placebo-controlled immunopathologic study of four months of inhaled corticosteroids in asthma. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 1994. 150:17–22.

8. Tashkin DP, Altos MD, Bleecker ER, Connett JE, Kanner RE, Lee WW, et al. The lung health study: airway responsiveness to inhaledmethacholin in smokers with mild to moderate airflow limitation. Am Rev Respir Dis. 1992. 145:301–310.

9. Crapo RO, Casaburi R, Coates AL, Enright PL, Hankinson JL, Irvin CG, et al. Guidelines for methacholine and exercise challenge testing-1999: this official statement of the American thoracic society was adopted by the ATS board of directors, July 1999. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2000. 161:309–329.

10. Sparrow D, O'Connor G, Colton T, Barry CL, Weiss ST. The relationship of nonspecific bronchial responsiveness to the occurrence of respiratory symptoms and decreased levels of pulmonary function: the Normative Aging Study. Am Rev Respir Dis. 1987. 135:1255–1260.

11. Taylor RG, Joyce H, Holland F, Pride NB. Bronhcial reactivity to inhaled histamine and annual rate of decline in FEV1 in male smokers and ex-smoker. Thorax. 1985. 40:9–16.

12. Rhee YG, In BH, Lee YD, Lee YC, Lee HB. Prevalence of combined bronchial asthma with COPD in patients with moderate to severe air flow limitation. Tuberc Respir Dis. 2003. 54:386–394.

13. Sciurba FC. Physiologic similarities and differences between COPD and asthma. Chest. 2004. 126:2 Suppl. 117S–124S.

14. Mannino DM, Gagnon RC, Petty TL, Lydick E. Obstructive lung disease and low lung function in adults in the United States: data from the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey, 1988-1994. Arch Intern Med. 2000. 160:1683–1689.

15. Fabbri LM, Romagnoli M, Caorbetta L, Casoni G, Busljetic K, Turato G, et al. Differences in airway inflammation in patients with fixed airflow obstruction due to asthma or chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2003. 167:418–424.

16. Oh SH, Hong CS, Lee HC, Huh KB, Lee WY, Lee SY. Evaluation of clinical significance of methacholine challenge test in asthma, allergic rhinitis, and chest symptom patients. Korean J Med. 1985. 29:599–605.

17. Fish JE. Middleton E, editor. Bronchial provocation testing. Allergy: principles and practice. 1993. 4th ed. St.Louis: Mosby-Year Book.

18. Ramsdell JW, Nachtwey FJ, Moser KM. Bronchial hyperreactivity in chronic obstructive bronchitis. Am Rev Respir Dis. 1982. 126:829–832.

19. Bahous J, Cartier A, Ouimet G, Pineau L, Malo JL. Nonallergic bronchial hyperexcitability in chronic bronchitis. Am Rev REspir Dis. 1984. 129:216–220.

20. Yan K, Salome CM, Woolcock AJ. Prevalence and nature of bronchial hyperresponsiveness in subjects with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Am Rev Respir Dis. 1985. 132:25–29.

21. Verma VK, Cockcroft DW, Dosman JA. Airway responsiveness to inhaled histamine in chronic obstructive airway disease: chronic bronchitis versus emphysema. Chest. 1988. 94:457–461.

22. Rijcken B, Schouten JP, Weiss ST, Rosner B, de Vries K, van der Lende R. Long term-variability of bronchial responsiveness to histamine in a random population sample of adults. Am Rev Respir Dis. 1993. 148:944–949.

23. Perpina M, pellicer C, de Diego A, Compte L, Macian V. Diagnostic value of the bronchial provocation test with methacholine in asthma: a Bayesian analysis approach. Chest. 1993. 104:149–154.

PDF

PDF ePub

ePub Citation

Citation Print

Print

XML Download

XML Download