Abstract

Thiamine (vitamin B1) serves as an important cofactor in body metabolism and energy production. It is related with the biosynthesis of neurotransmitters and the production of substances used in defense against oxidant stress. Thus, a lack of thiamine affects several organ systems, in particular the cardiovascular and nervous system. The cardiac insufficiency caused by thiamine deficiency is known as cardiac beriberi, with this condition resulting from unbalanced nutrition and chronic excessive alcohol intake. Given that the disease is now very rare in developed nations such as Korea, it is frequently missed by cardiologists, with potentially fatal consequences. Herein, we present a case study in order to draw attention to cardiac beriberi. We believe that this case will be helpful for young cardiologists, reminding them of the importance of this forgotten but memorable disease.

Thiamine, or vitamin B1, is a water-soluble vitamin with a biologically active form known as thiamine pyrophosphate, which plays a critical role in carbohydrate metabolism and produces essential glucoses for energy by acting as coenzyme.1)2) Thiamine deficiency (TD), or beriberi disease, generally refers to the lack of this active form. TD renders pyruvate and some amino acids unavailable in many systems, with the cardiovascular system being particularly vulnerable. Prior studies have demonstrated that TD exerts an unfavorable effect on cardiac contractility in the long term, which can clinically manifest as heart failure.3-5) As clinically evident TD is now very rare in the developed countries and most patients have no symptoms or signs, its diagnosis is commonly missed without any suspicion.6)7) However, when there is an undernourished dietary history and chronic alcohol intake, physicians can reasonably suspect this disease. The severity of potential outcomes if it is left untreated makes it essential for cardiologists to have an understanding of this condition and its optimal treatment.

We herein present one case of cardiac beriberi in which optimal and timely treatment induced dramatic improvement in left ventricular (LV) systolic function.

A 72-year-old female presented at our emergency department with 1-week febrile sense, progressive dyspnea, and generalized edema. A few days prior to this presentation, she had experienced several loose stools with intermittent abdominal pain localized to the right upper quadrant for four months.

She denied smoking or using illicit drug use, but confessed excessive and protracted alcohol consumption and a dietary pattern restricted to intake of only carbohydrates; specifically, eating only cookies without any intake of essential nutrients.

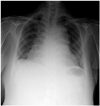

On admission, she appeared to be chronically ill-looking, but alert with mild hyperventilation. Her vital signs were a blood pressure of 134/95 mm Hg, heart rate of 83 beats/min, and body temperature of 36.5℃. Peripheral oxygen saturation was approximately 100% without oxygen supplementation despite subjective dyspneic complaint. She had icteric sclera without evidence of anemia on physical examination. Her neck veins were not distended, and irregular heartbeats without a murmur were auscultated. A normal breathing sound was heard on whole lung field. There was a tender, enlarged and palpable liver below the right costal margin, but shifting dullness or visualized distended veins on the abdominal wall were not observed. The spleen was not palpable. Both lower extremities were warm to touch and showed minimal edema in a symmetrical fashion. Neurologic examination revealed no abnormalities. Electrocardiography demonstrated revealed premature atrial contraction with nonspecific ST-T segment change (Fig. 1). Her chest X-ray showed cardiomegaly with mild pulmonary congestion and pleural effusion (Fig. 2). Laboratory parameters included mild elevations in the level of liver enzymes, total bilirubin, and high sensitive-C reactive protein (hs-CRP); aspartate transaminase (AST) 44 IU/L (0-40), alanine transaminase (ALT) 64 IU/L (0-40), total bilirubin 1.7 mg/dL (0.2-1.2), and hs-CRP 0.7 mg/dL (<0.5). Results of the initial arterial blood gas analysis, electrolyte levels, thyroid function test and cardiac enzymes like creatinine kinase (CK), CK-MB, and troponin-I were all within the normal range. For further cardiac evaluation, echocardiogram and cardiac magnetic resonance imaging (CMR) were performed. Transthoracic echocardiography showed LV global hypokinesia with severe reduction in LV systolic function (as demonstrated by an LV ejection fraction of 20%), and dilated LV cavity (as shown by an LV end-diastolic dimension of 70 mm). In addition, functional mitral/tricuspid regurgitation in association with a moderate degree of pulmonary hypertension (estimated systolic pulmonary artery pressure of 60 mm Hg), and small amount of pericardial effusion were noted (Fig. 3A and B). The CMR result allowed the exclusion of ischemic cardiomyopathy on the basis of the absence of myocardial delayed enhancement (Fig. 4) and the lack of evidence of myocardial perfusion abnormality.

Based on the patient's history of excessive alcohol consumption in combination with nutritional insufficiency, as well as cardiac imaging findings suggestive of dilated cardiomyopathy, cardiac beriberi was highly suspected. Intravenous thiamine administration was initiated for the next seven days, which was subsequently switched to oral vitamin B complex. With thiamine supplementation, the patient's condition steadily and gradually improved. Liver enzymes and total bilirubin were restored to normal levels a week later, and she was given permission to leave hospital two weeks after admission.

Follow-up echocardiography performed six months later revealed that her cardiac condition had dramatically improved: LV end-diastolic dimension decreased from 70 mm to 61 mm with a concomitant increase in LV ejection fraction to 43%, systolic pulmonary artery pressure was significantly decreased to 38 mm Hg, and the pericardial effusion that was present before the initiation of treatment was gone (Fig. 3C and D). The patient's subjective complaints of dyspnea and generalized edema were also no longer present.

Cardiac beriberi has been repeatedly reported for centuries all over the world, although it is very rare in the contemporary era, especially in developed countries.6) Many studies have emphasized the need for clinical suspicion of cardiac beriberi in patients with heart failure presenting with high risk clinical conditions, because in such cases the appropriate replacement of thiamine can to a large extent prevent devastating consequences and significantly improve cardiac function. Currently, the diagnosis of this disease depends on the following three factors: 1) clinical symptoms related to heart failure and a characteristic history of dietary inadequacy in combination with excessive alcohol intake, 2) exclusion of other etiologic types of heart disease, and 3) therapeutic response to thiamine administration.1) Although the diagnostic process seems rather to be straightforward, it is frequently difficult to draw a definite conclusion of cardiac beriberi because the clinical manifestations are not usually pathognomonic.8)9) Even with the support of sophisticated, contemporary cardiac imaging modalities like echocardiography and CMR, the diagnosis of cardiac beriberi is commonly missed. Thanks to its easy, rapid, and noninvasive nature, transthoracic echocardiography is considered the imaging modality of choice in the initial as well as the follow-up evaluation of a variety of cardiomyopathies. However, the echocardiographic findings for cardiac beriberi are very similar to those for other forms of dilated cardiomyopathy, i.e., a reduction in LV systolic function and LV enlargement with or without valvular regurgitation. As such, we cannot establish a diagnosis of cardiac beriberi based exclusively on echocardiography.8)10) Notably, there have been several recent studies suggesting the potential role of CMR in diagnosis,11)12) on the basis that cardiac beriberi has been reported to have characteristic CMR findings such as a decrement in LV ejection fraction with LV enlargement, global LV hypokinetic motion, and increased T2 signal intensity due to myocardial edema.11) However, myocardial edema, apart from LV systolic dysfunction, is not a specific finding for cardiac beriberi. Besides this, myocardial edema may not always be present in cardiac beriberi, as was true in the present case. Rather than for diagnosis confirmation, CMR can be used to exclude the possibility of ischemic cardiomyopathy without relying on invasive coronary angiography. Given the lack of pathognomonic findings in echocardiography and CMR, the need for thorough history taking cannot be overemphasized. It was through the history of alcohol abuse and insufficient dietary nutritional intake that cardiac beriberi could be diagnosed in our patient.

We did not place an order for laboratory confirmation of TD. Blood levels of thiamine pyruvate, alpha-ketoglutarate, lactate, glyoxylate or urinary excretion of thiamine and its metabolites may be measured to support and confirm the diagnosis, and the scarcity of any of these may help to confirm the diagnosis of beriberi.13) However, measurement of these chemicals is time- and cost-consuming, and may also cause delays in diagnosis and treatment. Thus, for these clinical reasons, thiamine replacement as a therapeutic trial is considered the most feasible approach. If the patient responds to this empirical thiamine replacement favorably, it is safe to conclude that the heart failure is attributable to TD. This approach is further supported by the non-toxic nature of thiamine, even at high blood levels.

Hepatic dysfunction can be present in cardiac beriberi, with this usually manifesting as mild elevation of AST and ALT levels. Chronic alcohol intake itself and/or ischemic hepatitis secondary to decreased perfusion caused by decreased LV systolic function can account for these laboratory abnormalities being observed.14)

In conclusion, cardiac beriberi secondary to TD is not straightforward to diagnose because of its nonspecific symptoms and signs. Therefore, a conglomeration of findings from careful history taking, physical examinations, and contemporary cardiac imaging modalities should form the basis for correct and early diagnosis of cardiac beriberi, which will significantly contribute to the initiation of time-dependent proper treatment. Although this condition is now relatively infrequent in the developed world, cardiologists should still take into account cardiac beriberi as a potential diagnosis in patients with LV systolic dysfunction and heart failure.

Figures and Tables

Fig. 1

Electrocardiography (ECG). ECG on admission revealed premature atrial contraction with nonspecific ST-T change.

Fig. 3

Transthoracic echocardiography. A: dilated LV cavity and depressed systolic function (Initial). B: moderate to severe functional MR and TR (Initial). C: improved LV size and heart function (6 months later). D: mild MR (6 months later). LV: left ventricule, MR: mitral regurgitation, TR: tricuspid regurgitation.

References

1. Jones RH Jr. Beriberi heart disease. Circulation. 1959; 19:275–283.

2. Astudillo L, Degano B, Madaule S, et al. Development of beriberi heart disease 20 years after gastrojejunostomy. Am J Med. 2003; 115:157–158.

3. Cappelli V, Bottinelli R, Polla B, Reggiani C. Altered contractile properties of rat cardiac muscle during experimental thiamine deficiency and food deprivation. J Mol Cell Cardiol. 1990; 22:1095–1106.

4. Sriram K, Manzanares W, Joseph K. Thiamine in nutrition therapy. Nutr Clin Pract. 2012; 27:41–50.

5. Wooley JA. Characteristics of thiamin and its relevance to the management of heart failure. Nutr Clin Pract. 2008; 23:487–493.

6. Yang JD, Acharya K, Evans M, Marsh JD, Beland S. Beriberi disease: is it still present in the United States? Am J Med. 2012; 125:e5.

7. Towbin A, Inge TH, Garcia VF, et al. Beriberi after gastric bypass surgery in adolescence. J Pediatr. 2004; 145:263–267.

8. Rao SN, Chandak GR. Cardiac beriberi: often a missed diagnosis. J Trop Pediatr. 2010; 56:284–285.

9. Naidoo DP, Gathiram V, Sadhabiriss A, Hassen F. Clinical diagnosis of cardiac beriberi. S Afr Med J. 1990; 77:125–127.

10. Lahey WJ, Arst DB, Silver M, Kleeman CR, Kunkel P. Physiologic observations on a case of beriberi heart disease, with a note on the acute effects of thiamine. Am J Med. 1953; 14:248–255.

11. Essa E, Velez MR, Smith S, Giri S, Raman SV, Gumina RJ. Cardiovascular magnetic resonance in wet beriberi. J Cardiovasc Magn Reson. 2011; 13:41.

12. Voigt A, Elgeti T, Durmus T, et al. Cardiac magnetic resonance imaging in dilated cardiomyopathy in adults--towards identification of myocardial inflammation. Eur Radiol. 2011; 21:925–935.

13. Lu J, Frank EL. Rapid HPLC measurement of thiamine and its phosphate esters in whole blood. Clin Chem. 2008; 54:901–906.

14. Naidoo DP. Beriberi heart disease in Durban. A retrospective study. S Afr Med J. 1987; 72:241–244.

PDF

PDF ePub

ePub Citation

Citation Print

Print

XML Download

XML Download