Abstract

The ‘equivalent-or-more-but-not-the-same-data’ provision in the Regulation on the Safety and Efficacy Evaluation of New Drug in Korea has served as the de facto data exclusivity term for any drug identical to a product subject to new drug reexamination. The legal debate that occurred between Abbott Korea and Hanmi in association with the approval of their sibutramine products, i.e., Reductil® vs. Slimmer®, showed why data exclusivity plays an important role to protect intellectual property of the innovator drug when incrementally modified drugs had to rely on the safety and efficacy data of the innovator drug for approval. The regulatory science and legal issues regarding the case of Reductil® vs Slimmer® were discussed, and the importance of data exclusivity was emphasized as a useful tool to protect intellectual property besides patent.

All the Korean regulations and other legal documents cited or used as reference in this commentary were representing the most updated versions at the time of writing the initial draft of this commentary (December, 2004) unless noted otherwise. The article numbers were changed as the regulations underwent some minor modifications since then, but the legal requirements are still the same and effective as of May, 2018.

According to Articles 5.10 and 3.2.8 of the Regulation on the Safety and Efficacy Evaluation of New Drug in Korea (the ‘Regulation’ hereafter),[1] for any identical drug product to a product subject to New Drug Reexamination (‘Reexamination’ hereafter), approval can only be granted if and only if the sponsor has the safety and efficacy data, equivalent to or more than the original data, but not the same data as the original data submitted by the innovator company when the first approval was made. Exemption from this ‘equivalent-or-more-but-not-the-same-data’ requirement can be sought only when the innovator company grants other companies to use their data, but this is highly unlikely.

This exclusivity provision was introduced in 1995 when the then Bureau of Pharmaceutical Affairs and Policies, Ministry of Health and Welfare, in Korea, which later became first the Korea Food and Drug Administration (KFDA), and then the Ministry of Food and Drug Safety (MFDS), mandated reexamination or postmarketing surveillance for certain prescription drugs (e.g., new drug of new molecular entity) for 4 or 6 years. This was to meet the requests from the United States, European Union, and Japan to extend the patent for ‘pipeline’ products (i.e., drug applications pending at the time of the Patent Act was passed in Korea in July 1987).

Sibutramine hydrochloride is the active ingredient of Reductil®, which was approved for the treatment of obesity in July 2001 in Korea. Abbott Korea Limited (‘Abbott Korea’ hereafter) was the market holder of Reductil® and it was subject to Reexamination until July 2007. Hanmi Pharmaceutical Co., Limited (‘Hanmi’ hereafter) developed a new salt of sibutramine (i.e., sibutramine mesylate, Slimmer®) and submitted the results of the phase I and III clinical trials with Slimmer®, coupled with some nonclinical data, to KFDA in an attempt to get the drug approved. Their argument was that the exclusivity provision applies only to a product ‘identical’ to a reexamination product. In other words, Hanmi contended that sibutramine mesylate or Slimmer® is not identical to sibutramine hydrochloride or Reductil® by virtue of the different salt, so they were legally entitled to seeking an approval for it even before the examination period for Reductil® ended (i.e., July, 2007) pursuant to Article 7.6 of the Regulation (data exemption provision). This data exemption provision allows the sponsor to seek an approval for a new salt or isomer of an already approved drug by submitting abridged data only (i.e., the results of clinical studies).

Prompted by Hanmi's attempt to get their Slimmer® approved, Abbott Korea requested KFDA in July 2004 clarify the regulatory issues related to the approval of a new salt of a product subject to reexamination. Responding to Abbott Korea's request, on October 15, 2004, KFDA upheld Abbott Korea's position and made clear that a new salt of a reexamination drug could not be approved unless the sponsor submitted ‘equivalent-or-more-but-not-the-same-data’ on the safety and efficacy of the drug. Based on this, Hanmi's submission was rejected by KFDA. Since then, Hanmi had to wait until July 1, 2007 when the reexamination period for Abbott Korea's Reductil® ended to have KFDA approve Slimmer®.

In the meantime, KFDA asked Jung-Il Park, an attorney at law and legal consultant to KFDA, for comments on the approval issue of a different salt of sibutramine.[2] Interestingly, Park came to the totally opposite conclusion that sibutramine mesylate could be viewed as not identical to Reductil®, therefore fully qualified for review by KFDA to get the drug approved through Article 7.6 of the Regulation. Park went even further, contending Article 5.10 of the same regulation did not conform to generally accepted legal principles, and, therefore was susceptible to being nullified or even unconstitutional. Park argued that Article 5.10 of the Regulation limited the right to seek an approval, which must have been defined by or delegated from the upper level laws (i.e., the Pharmaceutical Act or equivalents).

The objective of this commentary was to investigate and discuss the regulatory issues regarding the case of Reductil® vs Slimmer®, particularly for data exclusivity, an important tool to protect intellectual property besides patent, which has been often not well recognized though. To this end, the author approached the issues, not only from the regulatory science perspective, but also from the legal points of view as long as and to the extent that they were related to the regulatory science issues.

From the regulatory science perspective, there were at least three discussion points in the case of Reductil® vs Slimmer®: misunderstanding the legal framework of approval for non-brand-name drugs (or innovator drugs), confusion about the differences between data exclusivity and patent as intellectual property right, and role of the data exclusivity provision in the Reexamination regulation in Korea. It is critical to focus on and streamline these regulatory issues because they could invariably reveal the original legal intention codified in Articles 5.10, 3.2.8, and 7.6 of the Regulation.

In the following sections, each of those regulatory issues was analyzed in detail, and a firm regulatory background was provided and discussed. References to the history of the US FDA and other regulatory agencies in the legal framework and philosophical background of non–brand-name drug approval were frequently made. Finally, the author discussed why Park's comments on the case of Reductil® vs. Slimmer® were not appropriate.

The foremost legal premise of drug approval is that the sponsor must submit a full range of information, by which the regulatory agency can determine whether the optimal use of a drug product is reasonably guaranteed in the intended clinical settings. This information is collectively referred to as the data on the safety and efficacy of a drug. Therefore, any sponsor who wants to obtain an approval for a drug product from the regulatory agency must go through a lengthy development period, during which nonclinical and clinical studies are conducted sequentially or in parallel to compile the necessary safety and efficacy data.

Many wrongly assume that this ‘submit-your-own-full-data’ principle applies only to the approval of a brand-name drug of new molecular entity. This view was also reflected in Park's comments and a series of feature articles on the sibutramine debate and related Reexamination issues.[2] However, this view is not correct. On the contrary, generic drugs were also put to the same regulatory requirement as new drugs, particularly after the Kefauver-Harris Amendment of the Food, Drug, and Cosmetic Act (1962) mandated that drugs be proven safe and effective prior to the FDA approval.

For drugs approved before the Kefauver-Harris Amendment (i.e., prior to 1962), generic drugs could be approved by filing a so-called ‘paper’ New Drug Application (NDA). The paper NDA was based solely on published scientific or medical literature on the chemical demonstrating that it was safe. After 1962, however, even a generic drug must show that it is effective, which would not be otherwise possible unless the generic company spent time and money conducting the clinical trials. Consequently, almost 150 drugs were off-patent after 1962, for which there were no generics until 1984.[3,4,5] In other words, generic companies did not want to spend the resources to enter into the market because it was too costly.

Clearly, this was an adverse situation for patients, who had to buy expensive, brand-name drugs, even after patents had expired. To remedy this generic drug ‘lag’, the US Congress passed the Drug Price Competition and Patent Term Restoration Act in 1984, usually referred to as the Hatch-Waxman Act. The Hatch-Waxman Act was codified to facilitate the introduction of quality generic drugs by lowering the entry bar for them, simultaneously giving some incentives to the research-intensive innovator drug manufacturers, which will be addressed in more detail in the next section. In any case, the key change was that bioequivalence between a brand-name drug and a generic drug became the main criteria for the approval of the generic drug on the assumption that bioequivalence data are effective surrogates for safety and efficacy. This assumption, in fact, leads to another assumption that products approved pursuant to bioequivalence would meet the same regulatory requirements (i.e., the safety and efficacy) as innovator drugs. These assumptions hold only if the regulatory agency was allowed to refer to the safety and efficacy findings of a previously approved brand-name drug, called the Reference Listed Drug (RLD). In other words, this reliance principle is the true underlying approval mechanism of a generic drug, supported by bioequivalence.

With the dramatic success effected by the Hatch-Waxman Act (i.e., more rapid and less expensive introduction of generic drugs), the reliance principle has been expanded to the approval of certain drugs, collectively known as 505(b)(2) drugs.[6] These are products with some modifications of or differences from a previously approved brand-name drug such as different dosage form, different dosage strength, different salt of the same active ingredient, and so forth.[7] Therefore, the 505(b)(2) drug is neither a completely new product nor a generic product. Unlike generic drugs, the regulatory agency may require some clinical and/or preclinical data depending on the type of a 505(b)(2) drug. Like generic drugs, however, it requires references to an RLD so that the reliance principle is again indispensable for any 505(b)(2) drug approval.

In this regard, Hanmi's sibutramine mesylate or Slimmer® was certainly a 505(b)(2) product with Abbott Korea's Reductil® as its RLD. As a result, reliance on the safe and efficacy data of Reductil® should have been crucial for the approval of Hanmi's sibutramine mesylate regardless of new data submitted by Hanmi unless they were new proprietary data covering the whole aspects of the safety and efficacy profiles for Slimmer®.

Therefore, the principal issue in the sibutramine debate was whether it was legal for the regulatory agency to rely on the proprietary safety and efficacy data of a previously approved brand-name drug (Reductil®) to determine the approvability of a non-brand-name drug (Slimmer®). This legitimacy of data reliance could become more complicated if the innovator already requested in writing that the regulatory agency not disclose or rely on their data to approve a non-brand-name drug as in the sibutramine debate pursuant to the data protection provision in Article 72.9 of the Pharmaceutical Affairs Act.

The Hatch-Waxman Act was an unprecedented attempt to achieve two seemingly contradictory objectives: making lower-cost generic copies of approved drugs more widely available, while granting extended patent protection to innovative drug developers to ensure adequate incentives to innovate.

As described in the previous section, manufacturers of generic drugs were required to independently prove the safety and efficacy of their products before the Hatch-Waxman Act was passed in 1984. They were prohibited from using the unpublished test results of the original innovator drug, which were considered trade secrets of its manufacturer. Therefore, the Hatch-Waxman Act streamlined the process for approving generic drugs by requiring only that manufacturers demonstrate bioequivalence to an already approved brand-name drug, simultaneously allowing the FDA to rely on the proprietary safety and efficacy data of a brand-name drug.

For balance, however, some incentives were necessary to compensate for the innovation brought by research-intensive drug manufacturers. Briefly, the Hatch-Waxman Act granted a period of additional marketing exclusivity to make up for the time that a patented pipeline drug had remained in development and was used for review by the regulatory agency. This extension of patented time was why the Hatch-Waxman Act was named the Patent Term ‘Restoration’ Act. This extension, however, could not exceed 5 years, and it could be additional to the 20 years originally granted by the first issuance of a patent.

Furthermore, the Hatch-Waxman Act granted a 5-year exclusivity for new molecular entities (i.e., new drugs whose active ingredient has never been approved under NDA). This exclusivity was implemented such that, once a new molecular entity was approved, a generic drug or version was not approved for 5 years from the date of approval. In other words, the exclusivity has provided the holder of an approved new drug application with ‘limited’ protection from new competition in the marketplace for the innovation represented by its approved drug product. This limited protection precludes approval of 505(b) (2) applications or generic drugs for prescribed periods. This exclusivity is referred as ‘data exclusivity’ because it, in effect, has prohibited FDA from relying on the safety and efficacy ‘data’ of an already approved innovator drug.

Why were both patent and data exclusivity necessary? To answer this question, it is important to understand the two different intellectual property rights for innovation: patent and data exclusivity. Patent is primarily based on a balance between the incentive to develop more innovative knowledge products in the future and highly restrictive powers to the knowledge owners at present.[8] These paradoxical objectives can be achieved by disclosing the contents for which a patent is sought, but allowing only the patent holder to use, explore, manufacture, and test the patented contents. In contrast, data exclusivity has a different purpose. It promises treating proprietary data as a trade secret for a limited period in exchange for requiring that pharmaceutical companies provide data on the safety and efficacy of a new drug. Patent does not protect the integrity and confidentiality of the proprietary data. Only data exclusivity can protect and safeguard the proprietary information included in the registration files against any type of unfair commercial use. However, data exclusivity is theoretically less restrictive than patent because it does not legally prevent other companies (e.g., generic companies or competitors) from generating their own proprietary data to get approval. Therefore, patent and data exclusivity must be viewed as two separate forms of intellectual property right. Both are necessary.

It is critically important to understand that data exclusivity has to be sufficiently enough to prohibit unfair commercial use by competitors via two-layer protection: nondisclosure and nonreliance. Nondisclosure is the government's responsibility not to allow any competitors to gain access to the proprietary safety and efficacy data of a brand-name drug. Nonreliance, although less obvious than nondisclosure, aims to prevent the regulatory agency from relying on or using the proprietary information of an innovator drug to compare, judge, extrapolate, and bridge the ‘limited’ safety and efficacy data or blood levels of a non–brand-name drug for approval.

Based on the limited information found in the public domain, Hanmi appeared to have completed phase 1 and 3 clinical trials of sibutramine mesylate and tried to submit the results of those two clinical studies along with a minimal amount of animal pharmacology and stability information on their product. In other words, the whole toxicology and major pharmacology data, proof-of-concept clinical data, dose-response data, and clinical pharmacology data (e.g., pharmacokinetics, special population, and drug–drug interaction) did not appear to be included in the registration package of sibutramine mesylate or Slimmer®.

The short list of the compiled data for sibutramine mesylate could be acceptable under the drug approval system in Korea in 2004. Certainly, Article 7.10 of the Regulation provided a path for the sponsor seeking an approval of a new salt of a non-reexamination drug to submit reduced data only. However, as repeatedly emphasized in the previous sections, the main approval mechanism for sibutramine mesylate was reliance on the proprietary data of Abbott Korea that should be protected against unfair commercial use by not only nondisclosure, but nonreliance, until the reexamination period of Reductil® ended in July, 2007.

Therefore, the main regulatory issue in the case of Reductil® vs Slimmer® was data exclusivity, specifically nonreliance, not how the term ‘identical drug product’ in Article 3.2.8 of the Regulation should be defined. In fact, the exclusivity provision collectively found in Articles 3.2.8 and 5.10 of the Regulation, summarized as the ‘equivalent-or-more-but-not-the-same-data’ requirement, was nothing but what codified data exclusivity and nonreliance that the data are protected against unfair commercial use by generic or non-brand-drug competitors. This requirement is clearly stipulated in Article 39.3 of the World Trade Organization's Agreement on Trade Related aspects of Intellectual Property rights (‘TRIPs’ hereafter) as follows:

“Members, when requiring, as a condition of approving the marketing of pharmaceutical or of agricultural chemical products which utilize new chemical entities, the submission of undisclosed test or other data, the origination of which involves a considerable effort, shall protect such data against unfair commercial use. In addition, Members shall protect such data against disclosure, except where necessary to protect the public, or unless steps are taken to ensure that the data are protected against unfair commercial use”. (Article 39.3, TRIPs)

This view is crucially important because Article 72.9 of the Pharmaceutical Affairs Act appeared to define data exclusivity as nondisclosure only. However, given the primary legal framework for the approval of non-brand-name drugs (i.e., reliance on the proprietary information of an innovator drug) and the fact that this information as trade secrets must be protected against unfair commercial disclosure or reliance, the data exclusivity provision found in the Regulation, in effect, should be viewed as averting the potential loophole of the regulatory agency's unlawful reliance to the proprietary safety and efficacy data owned by the innovator to approve a non-brand-name drug during the reexamination period.

Therefore, unlike some arguments that the data exclusivity provision in the Regulation provided unfair advantage for the innovator drug manufacturers, this provision has actually prevented the Korean Government from being retaliated by other World Trade Organization member states through, for example, the US ‘Super 301’ and the EU's Trade Barriers Regulation (EC 3286/94).

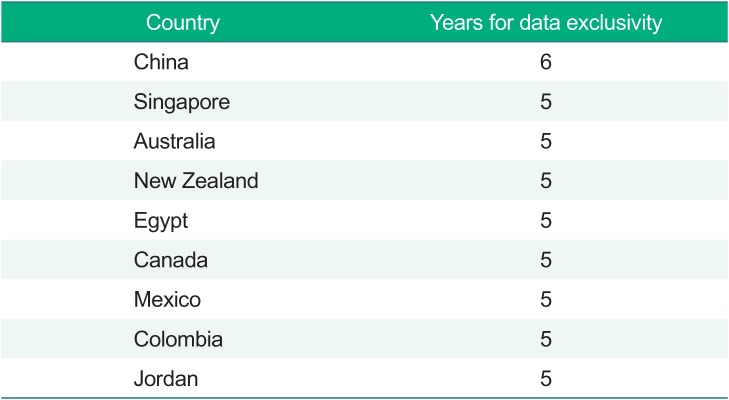

The period of data exclusivity (i.e., nonreliance) varies between different countries (Table 1).[9] For example, the United States gives 5 years of protection plus additional 3 years for the second indication (one time only), while the EU has adopted the ‘8+2+1’ formula, i.e., 8 years' data exclusivity, 2 years' marketing exclusivity, and an additional year for new indications of existing products. It is clear that the 6- or 4-years for data exclusivity through drug reexamination in Korea are not much different from the international standard.

The main points of Park's legal consult to KFDA could be summarized as follows[2]:

1) Hanmi's sibutramine mesylate is not identical to Abbott Korea's sibutramine hydrochloride. Therefore, it could be approved pursuant to Article 7.6 of the Regulation (i.e., the approval of a different salt or isomers of an already approved drug by submitting reduced amount of the safety and efficacy data) even before the reexamination period of Reductil® ended.

2) The data exemption provision in Article 7.6 of the Regulation should apply in the same manner both during and after Reexamination because its approval mechanism is to rely on the safety and efficacy data of a previously approved brand-name drug.

3) For the drug review, the regulatory agency could also refer to research papers including the safety and efficacy data different sponsors submitted.

4) The reexamination regulation in Korea is not to protect the exclusivity of brand-name drugs of research-intensive manufacturers that is not covered by the Patent Law.

5) Article 79.9 of the Pharmaceutical Affairs Act grants only data nondisclosure. Moreover, the review of a different salt of an already approved brand-name drug is necessary for the public benefit, so it does not violate the data protection provision of Article 79.9 of the Pharmaceutical Affairs Act.

6) Article 5.10 of the Regulation could be illegal or even unconstitutional because its ‘equivalent-or-more-but-not-the-same-data’ requirement provision, favoring research-intensive brand-name manufacturers, is not duly defined or properly delegated by the higher-level laws.

Of these comments, the last one—the possible unconstitutionality of Article of 5.10 of the Regulation—purely addressed the formality or hierarchy of different types of laws and regulations and their relationships. Therefore, this potential legal formality matter was not analyzed further in this commentary.

Park's comments showed that he did not fully understand the legal premise of non–brand-name drug approval (i.e., data reliance) and its ramifications in the protection of intellectual property rights, as codified in Articles 3.2.8 and 5.10 of the Regulation. For example, Park's second and third arguments were data exclusivity, and his fourth argument was also directly related to the role of the data exclusivity provision in the Reexamination regulation in Korea. These issues were already discussed in detail in the previous sections; thus, it is sufficient to comment that Park's arguments were lacking a serious understanding on the role of data exclusivity in the context of the Reexamination in Korea.

Then, what were the weaknesses found in Park's 1st and 5th arguments?

In a pure biopharmaceutical sense, Park might be correct, i.e., sibutramine mesylate is not identical to sibutramine hydrochloride. However, he was incorrect when he interpreted ‘Yoo-Hyo-Sung-Boon’ or effective moiety defined in Article 2 of the Regulation of the Review on the Applications to Manufacture or Import Drug Products and Related Products[10] is not ‘Hwal-Sung-Sung-Boon’ or active moiety because the same article defines Yoo-Hyo-Sung-Boon as a substance or mixture of substances that is expected to produce the effect of a drug product by its inherent pharmacologic action. Clearly, this definition indicates that Yoo-Hyo-Sung-Boon is sibutramine, not sibutramine hydrochloride or sibutramine mesylate, because sibutramine is the moiety that exerts its intended pharmacologic action in the body.

However, the process of defining an identical product is complicated because the Korean pharmaceutical laws do not provide a coherent and scientific definition of the terms in many cases. Furthermore, this definition issue was not as important as other issues such as data exclusivity, given that the true legal intention of Article 5.10 in the Regulation was to provide some protection mechanism against unfair commercial use of the proprietary safety and efficacy data of an innovator drug. In other words, it is not legitimate to take a word in a literal sense only because this literal interpretation would not certainly satisfy the original intention of the provision.

Furthermore, the regulatory issue could not be resolved even if Park's definition of an identical drug in the provision holds. If sibutramine mesylate was not an identical product to sibutramine hydrochloride in the regulatory perspective, then how was Hanmi going to be allowed to rely on the safety and efficacy data of what they argued were not identical to Reductil® of Abbott Korea? To put in a different way, if sibutramine mesylate was allowed to rely on the clinical and nonclinical data of sibutramine hydrochloride, the two products could not really be considered separate and nonidentical. This, in fact, was exactly the same point raised by the US Court of Appeals for the Federal Circuit that found it quite difficult to reconcile how Dr. Reddy's amlodipine maleate product could fall outside the scope of Pfizer's patent for amlodipine besylate or Novarsc® during its patent term extension, but at the same time Dr. Reddy could rely on the Novarsc® data to support its FDA approval.[11]

It is not scientifically valid or consistent to say that sibutramine mesylate is not identical to sibutramine hydrochloride while simultaneously insisting that the critical information for an optimal use of sibutramine mesylate should come from the safety and efficacy data of sibutramine hydrochloride. For example, dose-response data and clinical pharmacology data (e.g., pharmacokinetics, special population, and drug–drug interaction), which did not appear to be contained in the registration package of sibutramine mesylate, were actually the most important clinical data for prescribing practitioners. Therefore, how was it scientifically valid to report that the two products were not identical on one occasion, while insisting that the most significant information must rely on the data of a “different” product on subsequent occasions?

Park's 5th argument deserves a serious discussion. To restate his fifth argument, “the review of a different salt of an already approved brand-name drug is necessary for the public benefit, so it does not violate the data protection provision of Article 79.9 of the Pharmaceutical Affairs Act.” The author strongly believes that Park's fifth argument could inadvertently promote unconstitutional takings, and, therefore, was vulnerable to serious counter legal attacks.

An unconstitutional taking occurs when the Government or other public entities take private property for public use without just compensation. Article 23.3 of the Constitution of the Republic of Korea states: Expropriation (i.e., taking), use, or restriction of private property from public necessity and compensation therefore are governed by law. However, in such a case, just compensation must be paid.[12] For a regulatory action to be an unconstitutional taking, the action must interfere with a ‘Reasonable Investment-Backed Expectation (RIBE)’ of the property owner. Innovators, including Abbott Korea, want confidentiality (i.e., nondisclosure) and nonuse (i.e., nonreliance) of their proprietary safety and efficacy data. Therefore, nondisclosure and nonreliance are the two most important RIBEs, and these must be protected from unconstitutional takings without just compensation at least for the period that various statutory and regulatory provisions granted (e.g., 6 years for Reductil® through drug reexamination in Korea).

Moreover, takings must be limited to certain inevitable cases that satisfy ‘the principles of public necessity.’ Generally, the principles of public necessity can hold only if (1) there is a confirmed or specifically predicted public benefit, and (2) the violation can be minimized.[13] Moreover, all the legal conditions must be defined a priori by laws for a taking to be constitutional. Therefore, it cannot be said that a condition was satisfied to grant KFDA a taking of the property of Abbott Korea by disclosing or relying on the proprietary safety and efficacy data of Reductil® for the review, then approval, of Hanmi's Slimmer®. What Park argued in effect accidentally encouraged KFDA to uphold an unconstitutional taking, and this could be a detriment to any democratic nation.

The ‘equivalent-or-more-but-not-the-same-data’ provision in the Regulation on the Safety and Efficacy Evaluation of New Drug in Korea has served as the de facto data exclusivity for any drug identical to a product subject to new drug reexamination in Korea. The legal debate that occurred between Abbott Korea and Hanmi in association with the approval of their sibutramine products, i.e., Reductil® vs. Slimmer®, showed how data exclusivity could play an important role to protect intellectual property of the innovator drug when incrementally modified drugs had to rely on the safety and efficacy data of the innovator drug for approval.

Abbott Korea voluntarily withdrew Reductil® from the market in Korea on January, 2012 after MFDS recommended the drug be withdrawn after consultation with a Central Pharmaceutical Affairs Council (October, 2010).[14] The voluntary withdrawal decision was also prompted by a similar recommendation made by the US FDA. However, Hanmi's Slimmer® had remained in the market until August 4, 2017, when MFDS mandated the drug product recertificate system in Korea, resulting in the loss of marketing authorization for Slimmer®.[15]

References

1. Korea Food and Drug Administration. Regulation on the Safety and Efficacy Evaluation of New Drug. 2003. Notification 2003-17.

2. Jeon HM. Issues were raised on the legitimacy of protecting an innovator drug for which the patent has expired. Daily Pharm . 2004. 11. 17.

3. US Congress. H.R. REP. NO. 98-857, pt. 1. 1984. Accessed 28 May 2018. https://www.congress.gov/congressional-report/98th-congress/house-report/857/1.

4. Mossinghoff GJ. Overview of the Hatch-Waxman Act and Its Impact on the Drug Development Process. Food Drug Law J. 1999; 54:187–194. PMID: 11758572.

5. US Congress. H.R.3605 - Drug Price Competition and Patent Term Restoration Act of 1984. 1984. Accessed 28 May 2018. https://www.congress.gov/bill/98th-congress/house-bill/3605.

6. Food and Drug Administration HHS. Abbreviated New Drug Applications and 505(b)(2) Applications. Final rule. Fed Regist. 2016; 81:69580–69658. PMID: 27731961.

7. Food and Drug Administration, CDER. Guidance for Industry. Applications Covered by Section 505(b)(2). 10/1999. 1999. Accessed 28 May 2018. https://www.fda.gov/downloads/Drugs/Guidances/ucm079345.pdf.

8. Pugatch MP. University of Haifa ICTSD-UNCTAD Dialogue on Ensuring Policy Options for Affordable Access to Essential Medicines, Intellectual property and pharmaceutical data exclusivity in the context of innovation and market access. 2004.

9. Gorlin JJ. The Importance of Data Exclusivity. In : PhRMA Asia Managers Conference and Seminar; October 28, 2004; Shanghai, China.

10. Korea Food and Drug Administration. Regulation of the Review on the Applications to Manufacture or Import Drug Products and Related Products. 2003. 5. 09. Notification 2003-38.

11. PFIZER INC., vs. DR. REDDY'S LABORATORIES, LTD.: United States Court of Appeals for the Federal Circuit, 03-1227, -1258. 2004. 2. 27.

12. Constitution of the Republic of Korea, Article 23.3.

13. Lee MW. Structure of Article 23 of the Constitution of the Republic of Korea. Constitution Treatises. 2000; 11:323–324.

14. Ministry of Food and Drug Safety. Voluntary withdrawal of sibutramine from the market recommended. 2010. 10. 22. Accessed 28 May 2018. http://mfds.go.kr/antidrug/index.do?nMenuCode=53&boardSeq=2367&mode=view.

15. Cheon SH. Antiobesity drugs withdrawn from the market lost approval. 2017. 8. 04. Accessed 28 May 2018. http://www.biospectator.com/view/news_view.php?varAtcId=3728.

Table 1

Period of data exclusivity in selected countries

| Country | Years for data exclusivity |

|---|---|

| China | 6 |

| Singapore | 5 |

| Australia | 5 |

| New Zealand | 5 |

| Egypt | 5 |

| Canada | 5 |

| Mexico | 5 |

| Colombia | 5 |

| Jordan | 5 |

*Modified from [9].

PDF

PDF ePub

ePub Citation

Citation Print

Print

XML Download

XML Download