Abstract

Objective

To investigate the relationship between serum creatine kinase (CK) level and pulmonary function in Duchenne muscular dystrophy (DMD).

Methods

A total of 202 patients with DMD admitted to the Department of Rehabilitation Medicine, Gangnam Severance Hospital were enrolled from January 1, 1999 to March 31, 2015. Seventeen patients were excluded. Data collected from the 185 patients included age, height, weight, body mass index, pulmonary function tests including forced vital capacity (FVC), peak cough flow, maximal expiratory pressure (MEP), and maximal inspiratory pressure (MIP), and laboratory measurements (serum level of CK, CK-MB, troponin-T, and B-type natriuretic peptide). FVC, MEP, and MIP were expressed as percentages of predicted normal values.

Go to :

Duchenne muscular dystrophy (DMD) is an X-linked recessive inherited, neuromuscular disorder affecting one in 4,700 live male births [1]. It is characterized by progressive and severe muscle deterioration resulting from a lack of dystrophin, which provides structural stability to the muscle cell membrane [2].

The increased permeability of the sarcolemma leads to the release of creatine kinase (CK) from muscle fibers. Therefore, an increased level of serum CK is the hallmark of muscle damage. In patients with DMD, CK is markedly elevated compared with the normal range, which has diagnostic value. Furthermore, maximum serum CK activity is usually observed from 2 to 5 years of age in DMD, and progressively decreases as the disease progresses [3]. The decreasing rate of serum CK level has a stronger correlation with the progression of the dystrophic process than age [3].

Most patients with DMD die from respiratory failure and its resulting complications. Abundant research indicates that pulmonary functions in patients with DMD monotonically decline as they grow older due to dystrophic changes that occur in the respiratory musculature [4567]. However, whether the serum CK level can reflect pulmonary function is unknown.

The aim of this study was to investigate serum CK variability with age in a large group of patients with DMD, and to determine the relationship between serum CK level and pulmonary function in DMD.

Go to :

The study was conducted on the patients with DMD who were admitted to Gangnam Severance Hospital and had pulmonary function tests performed from January 1, 1999 to March 31, 2015. The majority of these patients had been monitored for many years. The diagnosis was made on the basis of clinical evaluation with genetic study or muscle biopsy. The exclusion criteria were patients whose clinical condition was not good enough to measure exact pulmonary function due to medical problems, and lack of testing for routine blood chemistry, including serum CK level. A retrospective analysis of the medical records of the patients was conducted.

Anthropometric variables including body weight (kg) and height (cm), were measured. Body mass index (BMI, kg/m2) was calculated as body weight divided by the square of height. Serum levels of CK (normal range, 35–232 U/L), CK-MB (normal range, 0–6.73 µg/L), troponin-T (Tn-T; normal range, 0.003–0.014 µg/L), and B-type natriuretic peptide (BNP; normal range, 0–100 pg/mL) were measured on the day of admission.

Pulmonary functions including respiratory muscle strength were evaluated by two physicians or a physician and research physical therapist. Forced vital capacity (FVC) was measured in the sitting and supine positions using a hand-held spirometer (Micro Spirometer; Micro Medical Ltd., Rochester, Kent, UK). Peak cough flow (PCF) was measured using an Assess Peak Flow Meter (Philips Respironics, Guildford, UK). The highest values of FVC and PCF were selected from at least three attempts. Maximal expiratory pressure (MEP) and maximal inspiratory pressure (MIP), reflecting the strength of respiratory muscles, were measured by a MicroRPM respiratory pressure meter (Micro Medical Ltd.) in the sitting position. Maximal values for MEP and MIP were selected from at least three attempts. FVC, MEP, and MIP were expressed as percentages of predicted normal values [8910].

Statistical evaluations were assessed using IBM SPSS Statistics ver. 20 (IBM, Armonk, NY, USA). The descriptive statistics are presented with mean±standard deviation (SD) and range for all parameters. Because this study is based on the assumption that serum CK level reflects respiratory muscle degeneration, advanced statistical analysis was conducted only for the serum CK level, except for the other variables. Pearson correlation coefficients were calculated to assess possible linear relationships between the respiratory variables and serum CK level. Simple linear regression analysis was performed to identify the influence of clinical parameters, including serum CK level, on the respiratory parameters, the dependent variables. Subsequently, to identify parameters that significantly contributed to pulmonary function, the variables of p<0.05 by simple regression analysis were included in multiple regression analysis. Due to the multicollinearity of weight, height, and BMI, only height was included in the model. All tests were two-sided and p<0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Go to :

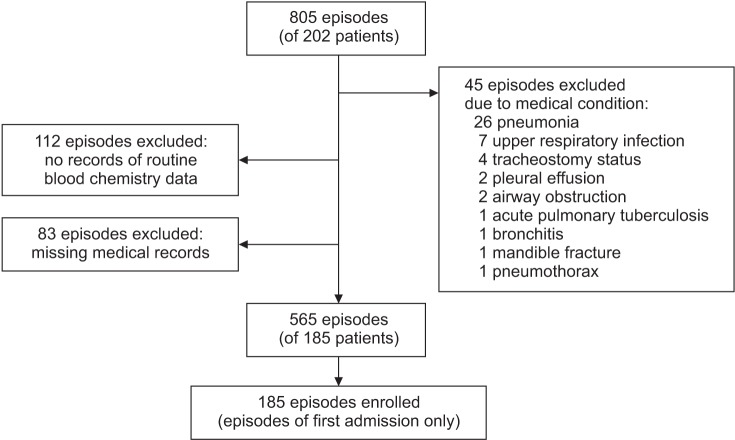

During the study period, 202 patients with DMD were admitted to Gangnam Severance Hospital, and the total number of repeated admission episodes was 805. Forty-five episodes when the patients' clinical conditions were not good enough to measure exact pulmonary function were excluded (these included pneumonia in 26 patients, upper respiratory infection in 7 patients, pleural effusion in 2 patients, bronchitis in 1 patient, pneumothorax in 1 patient, mandible fracture in 1 patient, airway obstruction in 2 patients, acute pulmonary tuberculosis in 1 patient, and tracheostomy tube insertion status in 4 patients). In addition, 112 episodes when the patients were not tested for routine blood chemistry, including serum CK level, were excluded, as were 83 episodes of patients whose medical records were missing. The remaining 185 patients (565 repeated episodes) were included for data analysis (Fig. 1). For statistical analysis, only the first admission episode was used in this study.

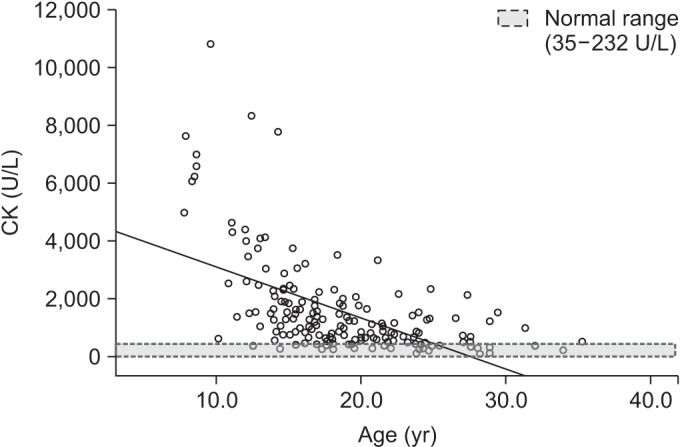

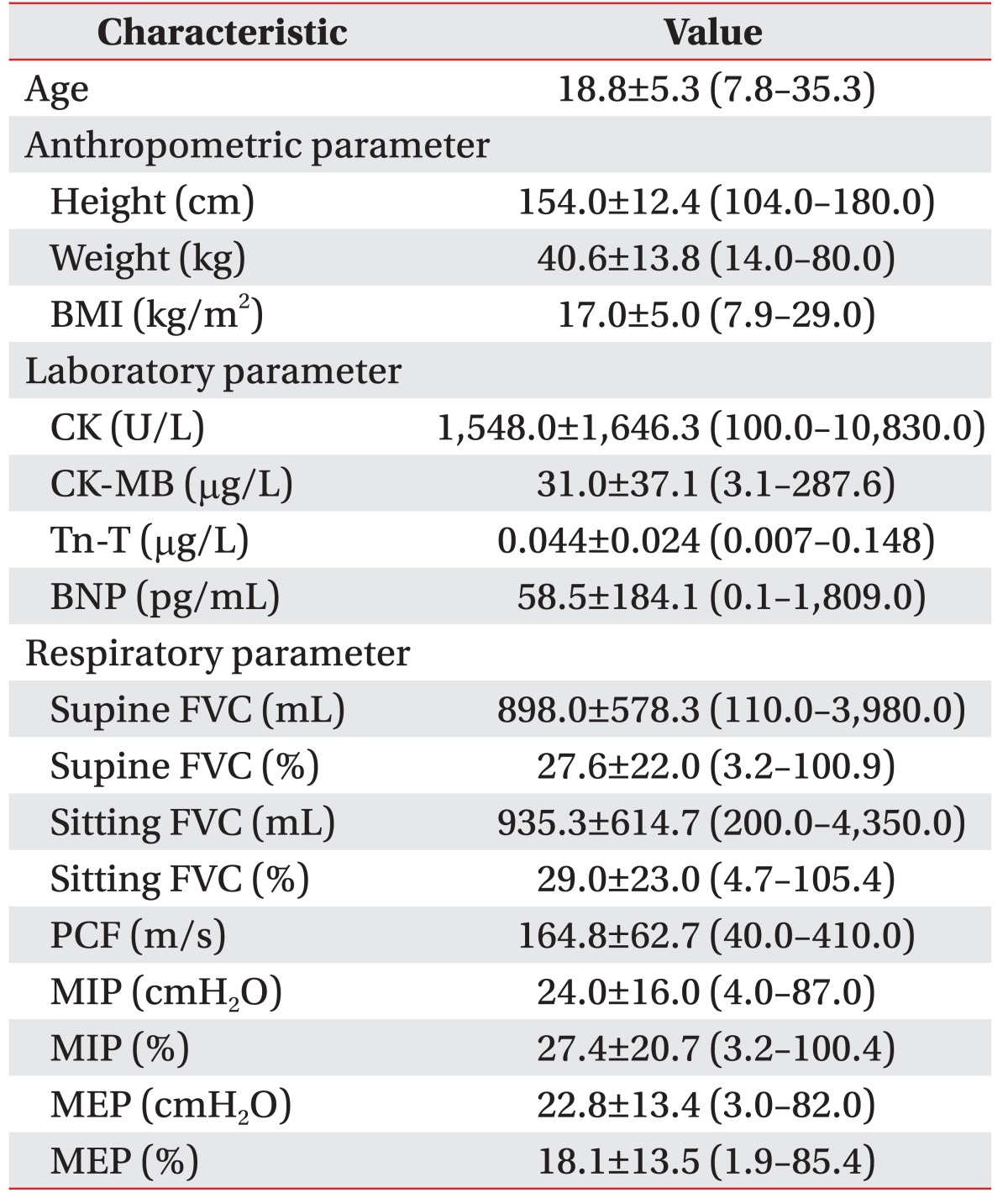

The mean age of 185 patients was 18.8±5.3 years (evenly distributed age of 7.8–35.3 years). The mean BMI was 17.0±5.0 kg/m2. The mean serum CK level was 1,547.9±1,646.2 U/L (Table 1). Furthermore, serum CK level progressively decreased with age. However, serum CK activities were elevated above normal even in the oldest group. Moreover, the serum CK level was maximally elevated to a level 46.7 times higher than the normal value (Fig. 2). The rate of decrease per year for serum CK level transformed by Napierian logarithm value was 10%. The mean serum levels of CK-MB and Tn-T were elevated above normal, and the mean BNP level was within normal range.

Mean±SD values of respiratory parameters were as follows: sitting FVC, 935.3±614.7 mL and 29.0%±23.0%; supine FVC, 898.0±578.3 mL and 27.6%±22.0%; PCF, 164.8±62.7 m/s; MIP, 24.0±16.0 cmH2O and 27.4%±20.7%; and MEP, 22.8±13.4 cmH2O and 18.1%±13.5%. The clinical parameters of the patients are summarized in Table 1.

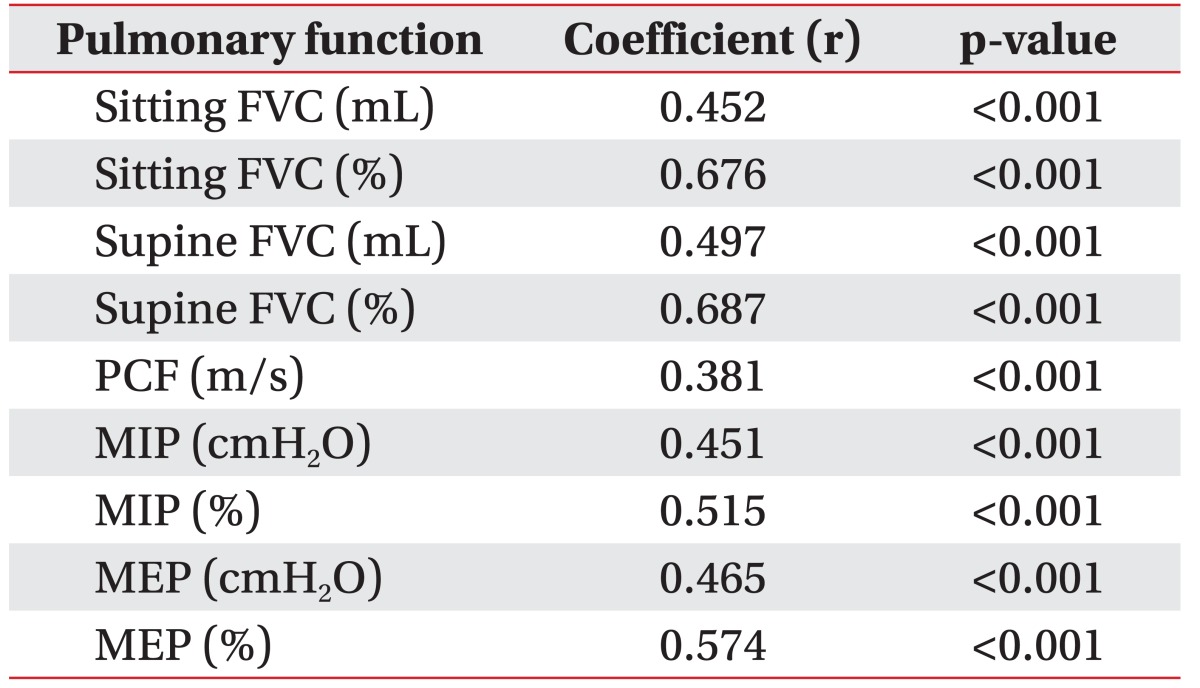

Serum CK level and all respiratory parameters were significantly correlated. This was particularly true for sitting FVC (%), supine FVC (%), MIP (%), and MEP (%) where there was strong positive relationship demonstrated by Pearson correlation coefficient values of 0.676 (p<0.001), 0.687 (p<0.001), 0.515 (p<0.001), and 0.574 (p<0.001), respectively (Table 2).

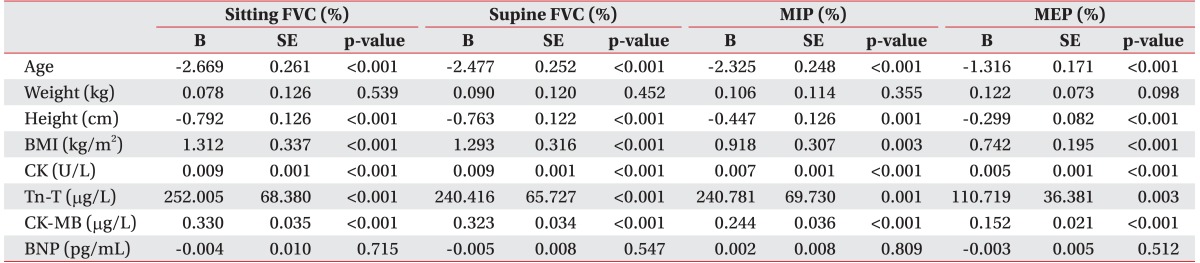

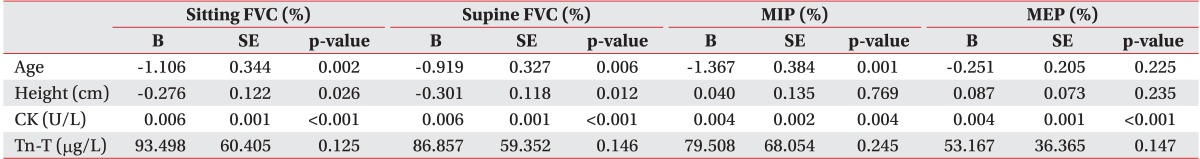

A multivariate regression model was used to identify the combination of variables that best predicted respiratory variables of interest. Prior to that, simple regression analysis was conducted to choose the variables using a multivariate regression model. Simple linear regression analysis showed that many variables were associated with sitting and supine FVC (%): age, height, BMI, Tn-T, CK, and CK-MB. A multivariate regression model was built using age, height, BMI, Tn-T, and CK as potential predictors. Because of a strong linear correlation with CK (Pearson coefficient=0.920, p<0.001), CK-MB was excluded from the multivariate regression model. Strong correlation was observed for CK, age, and BMI, followed by height (Tables 3, 4).

Go to :

In DMD serum CK is extremely elevated (10–100 times the normal level since birth), and the maximum activities of serum CK are observed from 2 to 5 years of age [3]. Consistent with this, we observed maximally elevated serum CK levels at 46.7 times higher than the normal levels. Furthermore, we observed the serum CK levels from 7.8 to 35.3 years of age in these patients. This is important because clinical parameters of patients with DMD aged over 20 years, and particularly over 30, are rarely reported. The Napierian logarithm value of serum CK level was used to assess the rate of decrease per year for serum CK for comparison with previous results [3]. The rate of decrease per year for serum CK level was 10%, which is lower than 18% [3] and 20% [3]. This may be due to the overall increase in life expectancy of patients that benefited from the advances in therapies including noninvasive ventilators.

The main finding from our study is that the serum CK levels were strongly correlated with FVC (%), MIP (%), and MEP (%), showing the strongest correlation with FVC (%). Most patients with DMD die from respiratory failure or conditions associated with it. However, pulmonary functions are the only known prognostic markers for patients with DMD [11]. Previous studies have suggested that pulmonary functions monotonically decline with age [4567]. However, other factors other than age that predict pulmonary functions have not been discovered. Furthermore, no studies have revealed a direct relationship between pulmonary function and serum CK in patients with DMD.

Increased serum CK activities reflect muscle degeneration. However, the serum CK level is extremely variable and ranges from normal to a fairly marked elevation; thus, it could be considered that disease severity is not closely associated with the serum CK level. Nevertheless, a few studies have been successful in elucidating the importance of serum CK. A previous study revealed that serum CK level is valuable in discriminating between DMD and other hereditary types of muscular dystrophy, and could be a more sensitive indicator of DMD than other clinical examinations [12]. In addition, declined serum CK level has been more strongly correlated with the Vignos scale age in patients with DMD, where serum CK levels represent the functional level of patients more accurately than their age [3]. The collective results indicate that the Vigno scale and pulmonary functions are correlated.

Interpretation of serum CK levels in patients with DMD could be promising in these aspects. Even though spirometry is a sensitive indicator of residual respiratory muscle function, it is not reliable in poorly cooperative patients and for some medical conditions affecting the lung parenchyma or airway. Considering this, measuring serum CK levels could be an alternative method, directly reflecting the residual respiratory muscle function even in the aforementioned conditions. Moreover, new treatments for dystrophic diseases that focus on restoring dystrophin in the skeletal muscle have been developed recently. Primary outcomes for these studies were dystrophin expression, motility, and life expectancy [13141516]. One study assessed the efficacy of the injection by comparing serum CK levels before and after intravenous gentamicin in boys with a nonsense mutation. Serum CK level declined with the use of the drug, indicating efficacy [16]. Serum CK could be an inexpensive, simple, and strong indicator assessing the success of therapeutic trials, particularly for pulmonary functions.

The limitation of this study is that only first hospitalization episodes were analyzed and used for the purpose of statistical applications. Further studies that focus on the parameter changes in each patient are required.

In conclusion, the serum CK activities were elevated above normal even in the oldest DMD group. Therefore, CK is a reliable screening test even in patients with advanced DMD. Serum CK was linearly associated with sitting and supine FVC (%), MIP (%), and MEP (%) in patients with DMD. Thus, serum CK is a strong predictor for pulmonary function in patients with DMD. Further studies are needed to clarify whether serum CK has an impact on pulmonary function so that pharmacological and newly developed genetic interventions can be assessed.

Go to :

References

1. Helderman-van den Enden AT, Madan K, Breuning MH, van der Hout AH, Bakker E, de Die-Smulders CE, et al. An urgent need for a change in policy revealed by a study on prenatal testing for Duchenne muscular dystrophy. Eur J Hum Genet. 2013; 21:21–26. PMID: 22669413.

2. Deconinck N, Dan B. Pathophysiology of Duchenne muscular dystrophy: current hypotheses. Pediatr Neurol. 2007; 36:1–7. PMID: 17162189.

3. Zatz M, Rapaport D, Vainzof M, Passos-Bueno MR, Bortolini ER, Pavanello Rde C, et al. Serum creatine-kinase (CK) and pyruvate-kinase (PK) activities in Duchenne (DMD) as compared with Becker (BMD) muscular dystrophy. J Neurol Sci. 1991; 102:190–196. PMID: 2072118.

4. Inkley SR, Oldenburg FC, Vignos PJ Jr. Pulmonary function in Duchenne muscular dystrophy related to stage of disease. Am J Med. 1974; 56:297–306. PMID: 4813648.

5. Hapke EJ, Meek JC, Jacobs J. Pulmonary function in progressive muscular dystrophy. Chest. 1972; 61:41–47. PMID: 5049500.

6. Rideau Y, Jankowski LW, Grellet J. Respiratory function in the muscular dystrophies. Muscle Nerve. 1981; 4:155–164. PMID: 7207506.

7. Hahn A, Bach JR, Delaubier A, Renardel-Irani A, Guillou C, Rideau Y. Clinical implications of maximal respiratory pressure determinations for individuals with Duchenne muscular dystrophy. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 1997; 78:1–6. PMID: 9014949.

8. Morris JF, Koski A, Johnson LC. Spirometric standards for healthy nonsmoking adults. Am Rev Respir Dis. 1971; 103:57–67. PMID: 5540840.

9. Polgar G, Promadhat V. Pulmonary function testing in children: techniques and standards. Philadelphia: Saunders;1971.

10. Wilson SH, Cooke NT, Edwards RH, Spiro SG. Predicted normal values for maximal respiratory pressures in Caucasian adults and children. Thorax. 1984; 39:535–538. PMID: 6463933.

11. Phillips MF, Quinlivan RC, Edwards RH, Calverley PM. Changes in spirometry over time as a prognostic marker in patients with Duchenne muscular dystrophy. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2001; 164:2191–2194. PMID: 11751186.

12. Pearce JM, Pennington RJ, Walton JN. Serum enzyme studies in muscle disease. II: Serum creatine kinase activity in muscular dystrophy and in other myopathic and neuropathic disorders. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 1964; 27:96–99. PMID: 14167093.

13. Haas M, Vlcek V, Balabanov P, Salmonson T, Bakchine S, Markey G, et al. European Medicines Agency review of ataluren for the treatment of ambulant patients aged 5 years and older with Duchenne muscular dystrophy resulting from a nonsense mutation in the dystrophin gene. Neuromuscul Disord. 2015; 25:5–13. PMID: 25497400.

14. Finkel RS, Flanigan KM, Wong B, Bonnemann C, Sampson J, Sweeney HL, et al. Phase 2a study of ataluren-mediated dystrophin production in patients with nonsense mutation Duchenne muscular dystrophy. PLoS One. 2013; 8:e81302. PMID: 24349052.

15. Bushby K, Finkel R, Wong B, Barohn R, Campbell C, Comi GP, et al. Ataluren treatment of patients with nonsense mutation dystrophinopathy. Muscle Nerve. 2014; 50:477–487. PMID: 25042182.

16. Malik V, Rodino-Klapac LR, Viollet L, Wall C, King W, Al-Dahhak R, et al. Gentamicin-induced readthrough of stop codons in Duchenne muscular dystrophy. Ann Neurol. 2010; 67:771–780. PMID: 20517938.

Go to :

PDF

PDF ePub

ePub Citation

Citation Print

Print

XML Download

XML Download