Abstract

Klebsiella pneumoniae (K. pneumoniae) can at times cause invasive infections, especially in patients with diabetes mellitus and a history of alcohol abuse. A 61-year-old man with diabetes mellitus and a history of alcohol abuse presented with abdominal and anal pain for two weeks. After admission, he underwent sigmoidoscopy, which revealed multiple ulcerations with yellowish exudate in the rectum and sigmoid colon. The patient was treated with ciprofloxacin and metronidazole. After one week, follow up sigmoidoscopy was performed owing to sustained fever and diarrhea. The lesions were aggravated and seemed webbed in appearance because of damage to the rectal mucosa. Abdominal computed tomography and rectal magnetic resonance imaging were performed, and showed a perianal and perirectal abscess. The patient underwent laparoscopic sigmoid colostomy and perirectal abscess incision and drainage. Extended-spectrum beta-lactamase-producing K. pneumoniae was identified in pus culture. The antibiotics were switched to ertapenem. He improved after surgery and was discharged. K. pneumoniae can cause rapid invasive infection in patients with diabetes and a history of alcohol abuse. We report the first rare case of proctitis and perianal abscess caused by invasive K. pneumoniae infection.

It is critical to treat perianal abscess with a proper selection of antibiotics as well as surgical drainage. Along with these treatments, efforts should be made to locate lesions and metastatic lesions associated with infection. Various aerobic/anaerobic strains might be responsible for perianal abscess. According to a recent study in Taiwan, Escherichia coli was the major pathogen responsible for perianal abscess in patients without a history of diabetes mellitus, whereas Klebsiella pneumoniae was found to be responsible in patients with diabetes.1

K. pneumoniae , a gram-negative short bacillus, causes invasive infections such as pneumonia and urinary tract infections, and is also known to be the major pathogen responsible for pyogenic hepatic abscess in Asia.2,3,4,5 Risk factors for invasive infections include diabetes mellitus and a history of abusive alcohol consumption.6,7,8 However, no study has been published focusing on K. pneumoniae-induced proctitis in South Korea or indeed other countries.

In the present study, we report the case of a patient with diabetes mellitus and a history of alcohol abuse, and review the relevant literature; the patient presented with severe K. pneumoniae-induced proctitis, as well as perianal abscess, and was thus treated with incision drainage and empiric antibiotics.

A 61-year-old man complained of abdominal pain and perianal pain, and was missing meals due to loss of appetite over two weeks before admission. He was hospitalized because his serum creatinine level was 5.28 mg/dL after examination at a nearby hospital. He was on medication for diabetes mellitus, which was diagnosed five years ago, and informed us that he had been drinking two bottles of Soju (Korean vodka, approximately 20% alcohol v/v) four times per week for the last 40 years. He drank particularly heavily every day over the two weeks prior to admission. Over the last 35 years, the patient had been smoking 1.5 packs of cigarettes per day.

At admission, his blood pressure, pulse, breathing rate, and body temperature were 106/68 mmHg, 100 pulse/min, 20 breaths/min, and 37.1℃, respectively. The patient had acute signs, abdominal pain, and mass lesions accompanying oppressive pain upon rectal examination. In subsequent blood tests, white blood cell count, hemoglobin, platelet count, and CRP were found to be 9,000/mm3, 12.6 g/dL, 43,000/mm3, and 23.29 mg/dL, respectively. In the biochemical analyses of serum, total protein, albumin, BUN, creatinine, total bilirubin, AST, ALT, glucose, and glycated hemoglobin were 7.5 g/dL, 3.3 g/dL, 82.2 mg/dL, 2.6 mg/dL, 2.28 mg/dL, 57 IU/L, 77 IU/L, 287 mg/dL, and 7.7%, respectively. Radiological examinations, such as abdominal CT to assess oppressive pain in abdominal and perianal areas, could not be performed owing to the elevated serum creatinine levels.

After sufficient supply of fluids, his creatinine level was normalized but he experienced a high fever (38-39℃) and diarrhea on the 4th day of hospitalization. Blood and fecal tests were performed, and ciprofloxacin (800 mg) was administered via intravenous injection. His symptoms were not alleviated, and he underwent sigmoidoscopy on the 7th day of hospitalization.

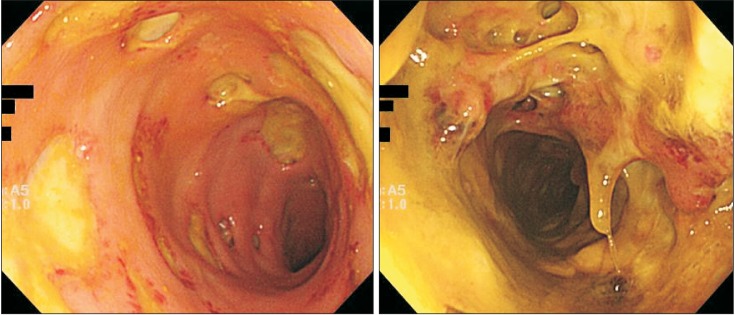

The endoscope was inserted up to the sigmoid colon (anal verge 30 cm). In the sigmoid colon, there was intestinal mucosa edema with gastric ulceration covered by yellowish exudates. Most ulcers were round-shaped and relatively deep, and their boundaries were clear and accompanied by rubefaction. In the rectum, more excessive yellowish extrudes were shown with deeper and bigger ulcerations, covering most of intestinal mucosa (Fig. 1). The bases and boundaries of the ulcerations were biopsied, and nonspecific chronic inflammation was found (Fig. 2).

In blood and stool culture tests, no strain was identified. Owing to the possibility of pseudomembranous colitis, stool culture and toxin tests were performed to check for Clostridium difficile infection, and metronidazole (1.5 g) was administered via intravenous injection. Even though the results were negative for C. difficile, and metronidazole was administrated, the patient still complained of fever and diarrhea, leading us to administer vancomycin (500 mg, orally) on the 10th day of hospitalization as an empiric prescription for a differential diagnosis of pseudomembranous colitis.

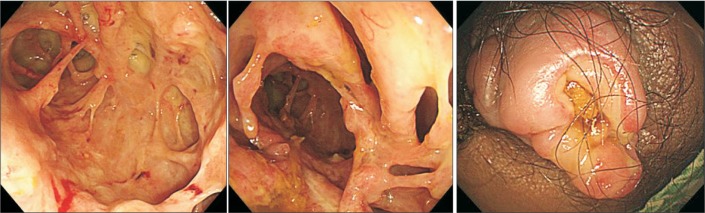

The administration of vancomycin did not alleviate his severe fever and diarrhea, and the patient therefore underwent follow up sigmoidoscopy. In the follow-up sigmoidoscopy, the lesions were found to be seriously aggravated. The entire rectum was covered with white-yellowish extrudes and the intestinal mucosa was damaged and had a spider web appearance (Fig. 3A). The intestinal mucosa was seriously damaged, and intestinal lumens were indistinguishable, making it impossible to insert the endoscope any further than the rectum. An abdominal CT scan was performed in order to monitor the range of lesions and their surroundings.

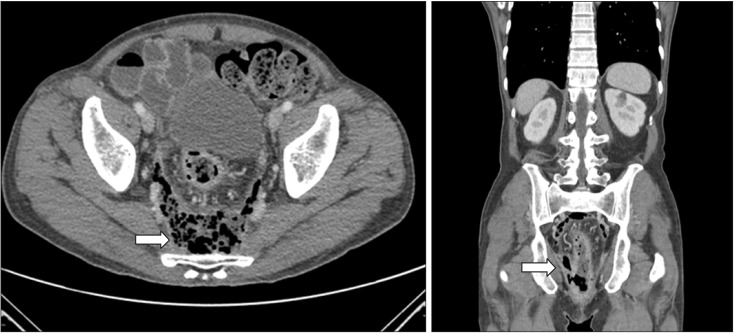

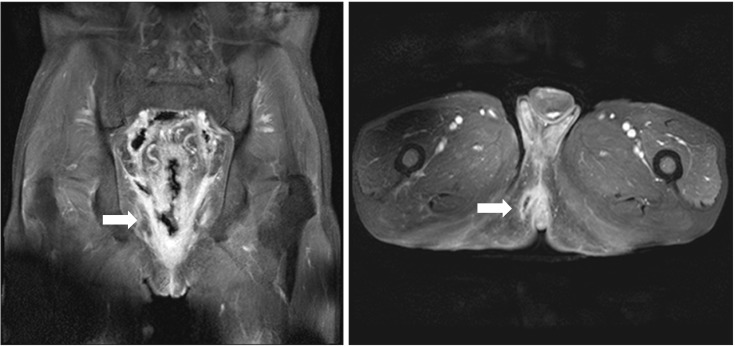

In addition, on the 15th day of hospitalization, the patient underwent rectal MRI as the mass-like lesions with oppressive pains in the anus had not improved, and an anal fistula opening accompanying ulcerations was suspected (Fig. 3B). Upon abdominal CT and rectal MRI, multiple edemas were found on the wall of the entire sigmoid colon and rectum, while the proximal colon and small intestinal walls seemed relatively normal. In and around the rectum and anus, there were abscesses accompanied by gas, rectal fistulas, and anal fistulas (Fig. 4 and 5). We deemed that internal medications would not be effective. Therefore, the patient underwent sigmoidostomy as well as perirectal abscess incision and drainage on the 16th day of hospitalization. Upon pus culture, the presence of extended-spectrum beta-lactamase producing K. pneumoniae was confirmed; therefore, the antibiotics were switched to ertapenem. Ertapenem (1 g) was administered intravenously over two weeks, and the patient was discharged on day 17 as his symptoms had improved.

According to a multi-institutional study, 21.1% of K. pneumoniae was found in the stool culture of healthy subjects. Of them, 4.9% represented serotype K1 K. pneumoniae.4

K. pneumoniae is able to form colonies in the oral cavity, skin, and intestines. K. pneumoniae can also cause invasive infections in the respiratory tract and urinary tract, and the major risk factors for such infections are excessive drinking and diabetes mellitus.9,10,11 In a recent study, it was found that K. pneumoniae was mainly responsible for perianal abscess in diabetes mellitus patients.1 Further, in another study, it was demonstrated that gram-negative strains were identified in 59% of cultures from the pharynx of chronic drinkers, of which K. pneumoniae was the most prevalent.12 Diabetes mellitus is known to impede white blood cell functions, chemotaxis, and phagocytosis, thereby increasing the risk of invasive infection.13 Drinking also increase the risks of invasive infection as it induces the dysfunction of macrophages, thymus-derived lymphocytes, and B lymphocytes, and hinders the formation of reactive oxygen species.14

The present case of a patient with diabetes mellitus and a history of alcohol abuse might be related to poor glycemic control due to daily drinking over the two weeks prior to hospitalization, thus allowing K. pneumoniae to form intestinal colonies and induce an invasive infection. In the pus culture, we were able to isolate extended-spectrum beta-lactamase-producing K. pneumoniae. This might be because general K. pneumoniae was responsible in an early stage of infection, and "superselection" occurred upon exposure to empiric antibiotics. In South Korea, invasive infections induced by K. pneumoniae commonly present with hepatic abscess, while some may cause metastatic infections too.3,15 In a study conducted in Taiwan, of 187 patients with primary liver abscess due to K. pneumoniae, 12.3% had metastatic infections.

Among the patients with metastatic lesions (23 patients), there were 14 cases (60.8%) of endophthalmitis, 10 cases (43.4%) of pulmonary abscess, six cases (26.0%) of brain abscess, five cases (21.7%) of prostate abscess, two cases (8.6%) of osteomyelitis, and one case (4.3%) of psoas abscess.16 In addition, in common with the present case, there are a few reports suggesting that K. pneumoniae can induce metastatic infections accompanying perianal abscess. For instance, Jung et al. reported that K. pneumoniae induced endogenous ophthalmitis accompanying abscess on the prostate as well as the tissue surrounding the anus. In another case, Lee et al. also reported chronic inflammatory demyelinating polyradiculopathy accompanying perianal abscess induced by K. pneumoniae.17,18 To the best of our knowledge, however, no study has been reported a case of K. pneumoniae-induced colitis/proctitis with perianal abscess in South Korea or other countries.

In the present case, empiric antibiotics did not alleviate K. pneumoniae-induced sigmoid colonic and rectal infections. Instead, the symptoms were aggravated, and fistula and abscess formed, leading us to perform surgical drainage. In a domestic study, the causative organism was identified in 40%19 of infectious colitis cases, while we were unable to isolate the causative organism in stool or blood cultures. Furthermore, it was not possible for us to find the causative organism from tissue culture or endoscopic biopsy, and empiric antibiotics were therefore provided.

Causative or accompanying lesions in the abdominal cavity were not identified because of acute renal failure present at admission, which made medical imaging tests impossible. No improvement in symptoms was found with antibiotic treatment, although renal function was improved. Therefore, abdominal contrast-enhanced CT was performed, revealing an abscess producing gas in the rectum and anus. Immediate surgical drainage was performed for the perianal abscess, and extended-spectrum beta-lactamase-producing K. pneumoniae was isolated from the abscess culture. The antibiotics were replaced with ertapenem, and proctitis and the perianal abscess subsequently improved. There are 77 serotypes of K. pneumoniae , and of these serotype K1 and K2 possess the most significant virulence and resistance to phagocytosis.20 Although we did not investigate the serotype of K. pneumoniae in this patient, it is likely that either serotype K1 or K2 K. pneumoniae induced the infections, giving rise to the rectal and perianal abscesses.

Even though infectious colitis is commonly treated with fluids and empiric antibiotics, immediate imaging examinations such as CT and MRI should be performed in situations where such antibiotics do not improve symptoms in order to diagnose complications such as fistula opening and abscess. In addition, early administration of proper antibiotics via appropriate culture tests using relevant specimens and immediate surgical means (e.g., drainage and fistulectomy) are warranted to prevent the necessity for major surgery.

The present report is the first domestic/international case report and literature review of a male patient with a history of diabetes mellitus and a history of chronic drinking treated with incision drainage and sigmoidostomy for perirectal/perianal abscess and fistula opening, as well as severe proctitis induced by K. pneumoniae infection. Early imaging tests, as well as appropriate treatments, are critical for the successful treatment of colitis that is not improved by the administration of fluids and empiric antibiotics.

References

1. Liu CK, Liu CP, Leung CH, Sun FJ. Clinical and microbiological analysis of adult perianal abscess. J Microbiol Immunol Infect. 2011; 44:204–208. PMID: 21524615.

2. Ryan KJ, Ray CG. Sherris medical microbiology: an introduction to infectious diseases. 4th ed. New York: McGraw-Hill Medical;2003.

3. Chung DR, Lee SS, Lee HR, et al. Emerging invasive liver abscess caused by K1 serotype Klebsiella pneumoniae in Korea. J Infect. 2007; 54:578–583. PMID: 17175028.

4. Chung DR, Lee H, Park MH, et al. Fecal carriage of serotype K1 Klebsiella pneumoniae ST23 strains closely related to liver abscess isolates in Koreans living in Korea. Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis. 2012; 31:481–486. PMID: 21739348.

5. Fang CT, Lai SY, Yi WC, Hsueh PR, Liu KL, Chang SC. Klebsiella pneumoniae genotype K1: an emerging pathogen that causes septic ocular or central nervous system complications from pyogenic liver abscess. Clin Infect Dis. 2007; 45:284–293. PMID: 17599305.

6. Ko WC, Paterson DL, Sagnimeni AJ, et al. Community-acquired Klebsiella pneumoniae bacteremia: global differences in clinical patterns. Emerg Infect Dis. 2002; 8:160–166. PMID: 11897067.

7. Tsay RW, Siu LK, Fung CP, Chang FY. Characteristics of bacteremia between community-acquired and nosocomial Klebsiella pneumoniae infection: risk factor for mortality and the impact of capsular serotypes as a herald for community-acquired infection. Arch Intern Med. 2002; 162:1021–1027. PMID: 11996612.

8. Lee KH, Hui KP, Tan WC, Lim TK. Klebsiella bacteraemia: a report of 101 cases from National University Hospital, Singapore. J Hosp Infect. 1994; 27:299–305. PMID: 7963472.

9. Mandell LA, Wunderink RG, Anzueto A, et al. Infectious Diseases Society of America/American Thoracic Society consensus guidelines on the management of community-acquired pneumonia in adults. Clin Infect Dis. 2007; 44(Suppl 2):S27–S72. PMID: 17278083.

10. Gaynes R, Edwards JR. Overview of nosocomial infections caused by gram-negative bacilli. Clin Infect Dis. 2005; 41:848–854. PMID: 16107985.

11. Czaja CA, Scholes D, Hooton TM, Stamm WE. Population-based epidemiologic analysis of acute pyelonephritis. Clin Infect Dis. 2007; 45:273–280. PMID: 17599303.

12. Fuxench-Lopez Z, Ramirez-Ronda CH. Pharyngeal flora in ambulatory alcoholic patients: prevalence of gram-negative bacilli. Arch Intern Med. 1978; 138:1815–1816. PMID: 363086.

13. Joshi N, Caputo GM, Weitekamp MR, Karchmer AW. Infections in patients with diabetes mellitus. N Engl J Med. 1999; 341:1906–1912. PMID: 10601511.

14. Szabo G. Consequences of alcohol consumption on host defence. Alcohol Alcohol. 1999; 34:830–841. PMID: 10659718.

15. Park GY, Kim SW, Kim HI, et al. Klebsiella pneumoniae as the most frequent pathogen of endogenous endophthalmitis. Korean J Med. 2012; 82:200–207.

16. Cheng DL, Liu YC, Yen MY, Liu CY, Wang RS. Septic metastatic lesions of pyogenic liver abscess. Their association with Klebsiella pneumoniae bacteremia in diabetic patients. Arch Intern Med. 1991; 151:1557–1559. PMID: 1872659.

17. Jung TS, Kim GW, Koh JI, et al. Endogenous Klebsiella endophthalmitis concurrent with prostate and perianal abscesses. Korean J Urol. 2008; 49:1055–1057.

18. Lee YS, Kim SY, Kim YJ, Lee EJ. A Case of chronic inflammatory demyelinating polyradiculoneuropathy associated with perianal abscess by Klebsiella pneumoniae. J Korean Child Neurol Soc. 2005; 13:94–98.

19. Eun CS, Han DS, Kim JP, et al. Comparative value of colonic tissue culture and stool culture for diagnosis of acute infectious colitis. Intest Res. 2004; 2:83–88.

20. Mizuta K, Ohta M, Mori M, Hasegawa T, Nakashima I, Kato N. Virulence for mice of Klebsiella strains belonging to the O1 group: relationship to their capsular (K) types. Infect Immun. 1983; 40:56–61. PMID: 6187694.

Fig. 1

Colonoscopic findings on the 7th day of hospitalization. Multiple, various-sized ulcers with yellowish exudate in the rectum and sigmoid colon are seen.

Fig. 2

Histologic findings. Intact mucosal architecture and non-specific chronic inflammation are seen (H&E stain, ×100).

Fig. 3

Colonoscopic findings on the 14th day of hospitalization. (A) Destroyed colonic mucosa with ulcers in the rectum is seen. (B) Perianal fistula opening and ulceration.

PDF

PDF ePub

ePub Citation

Citation Print

Print

XML Download

XML Download