Abstract

Background

To evaluate the effects of severe hypoglycemia without hypokalemia on the electrocardiogram in patients with type 2 diabetes in real-life conditions.

Methods

Electrocardiograms of adult type 2 diabetic patients during the episodes of severe hypoglycemia and the recovered stage were obtained and analysed between October 1, 2011 and May 31, 2012. Patients who maintained the normal serum sodium and potassium levels during the episodes of severe hypoglycemia were only selected as the subjects of this study. Severe hypoglycemia was defined, in this study, as the condition requiring active medical assistance such as administering carbohydrate when serum glucose level was less than 60 mg/dL.

Results

Nine type 2 diabetes patients (seven men, two women) were included in the study. The mean subject age was 73.2±7.7 years. The mean hemoglobin A1c level was 6.07%±1.19%. The median duration of diabetes was 10 years (range, 3.5 to 30 years). Corrected QT (QTc) intervals were significantly increased during the episodes of severe hypoglycemia compared to the recovered stage (447.6±18.2 ms vs. 417.2±30.6 ms; P<0.05). However, the morphology and the amplitude of the T waves were not changed and ST-segment elevation and/or depression were not found during the episodes of severe hypoglycemia.

Previous studies have shown that the incidence of severe hypoglycemia has increased [1,2]. Hypoglycemia causes recurrent morbidity in diabetes and can lead to death. It has been estimated that hypoglycemia is responsible for 2% to 4% of death in type 1 diabetes [3]. A retrospective cohort study has reported that patients with hypoglycemic episodes during hospitalization have higher mortality 1 year after discharge (27.8% for patients with at least one hypoglycemic episode vs. 14.1% for patients without hypoglycemic episodes) [4].

Several studies have demonstrated that insulin-induced hypoglycemia in diabetes causes the prolongation of corrected QT (QTc) interval, which is associated with ventricular arrhythmias and sudden death, and have reported that this abnormality in cardiac repolarization results from hypokalemia and an increase in serum catecholamines [5-7].

A study conducted to patients with type 2 diabetes with a continuous glucose monitoring system and continuous electrocardiogram (ECG) monitoring confirmed that hypoglycemia was associated with cardiac ischemia [8].

The aim of this study was to evaluate the effects of severe hypoglycemia without hypokalemia on the ECG in type 2 diabetes in real-life conditions.

In review of retrospective medical records, ECGs of adult type 2 diabetic patients were obtained and analysed during the episodes of severe hypoglycemia in the Emergency Department and the recovered stage in the general ward before they were discharged from the Saint Carollo Hospital between October 1, 2011 and May 31, 2012. For that period, a total of 43 type 2 diabetes with severe hypoglycemia were identified in the Emergency Department. Seventy-nine percentage (34/43) normokalemic patients, 14.0% (6/43) hypokalemic patients, and 7.0% (3/43) hyperkalemic patients were found. Patients who maintained the normal serum sodium and potassium levels during the episodes of severe hypoglycemia in the Emergency Department were chosen as the subjects for this study (Table 1). Severe hypoglycemia was defined, in this study, as the condition requiring active medical assistance such as administering carbohydrate when serum glucose level was less than 60 mg/dL [1,9].

Subject characteristics including age, gender, height, weight, the duration of diabetes and hypertension, glucose lowering agents, antihypertensive medications, smoking history, alcohol consumption, the inducing factor for hypoglycemia, and comorbidities (coronary artery disease and cerebral vascular disease) were obtained. HbA1c, plasma C-peptide levels, plasma insulin levels, and serum chemistry profiles were also obtained.

Analyses of the digital 12-lead ECG recordings were performed at a ECG paper speed of 25 mm/sec using a M1771A Pagewriter 200 (Phillips, Andover, MA, USA). QTc intervals were also simultaneously recorded at the digital 12-lead ECG recordings by an automatic method and corrected by Bazett's formula (Fig. 1).

T wave changes, ST-segment elevation and/or depression and changes in the QRS complex that occur in association with acute ischemia and infarction were assessed [10]. The ST-segment elevation was defined as >0.2 mV elevation in two or more precordial leads and >0.1 mV elevation in two or more limb leads. The ST-segment depression was defined as flat or down sloping depression >0.1 mV, lasting for at least 1 minute in two or more leads. Deeply inverted T wave was defined as the inverted T wave greater than 0.5 mV.

All data were analysed using the SPSS statistical program version 13.0 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA). The Wilcoxon's signed rank test was applied to compare the most of data.

Normally distributed data are presented as the mean value±standard deviation and nonnormally distributed data are presented as the median range. P values of less than 0.05 were considered as significant.

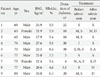

A total of nine patients (seven male, two female) were included in this study. The mean subject age was 73.2±7.7 years. The mean HbA1c level was 6.07%±1.19%. The median duration of diabetes was 10 years (range, 3.5 to 30 years). The mean body mass index was 23.0±2.9 kg/m2. Among the nine patients, eight patients were treated with glucose-lowering agents. All of them were taking a sulfonylurea derivative, glimepiride that affects the ATP-sensitive K+ channel. During the hospital admission, sulfonylureas was discontinued in 50% of the subjects and continued in the rest of them. The sulfonylureas was commenced in a patient once insulin therapy was discontinued (Table 2).

All patients had a medical history of hypertension and were taking antihypertensive medications which did not contain alpha and beta adrenergic blocking agents. However, none had a history of coronary artery disease. During the hospital admission, their antihypertensive medications were not changed.

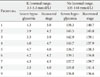

Serum potassium and sodium levels of all patients were within normal range during severe hypoglycema and the recovered stage (Table 1).

There were no significant differences in heart rates, RR intervals or QT intervals during the episodes of severe hypoglycemia but the QT intervals were slightly longer during the episodes of severe hypoglycemia than during the recovered stage (408.8±40.7 ms vs. 380.2±39.7 ms, P=0.066) (Table 3).

The QTc intervals were significantly increased during the episodes of severe hypoglycemia compared to the recovered stage in all patients (447.6±18.2 ms vs. 417.2±30.6 ms, P=0.008) (Table 3, Fig. 2). In particular, the QTc intervals were significantly increased in patients taking only oral glucose lowering agents during the episodes of severe hypoglycemia compared to the recovered stage (450.0±20.2 ms vs. 417.0±34.1 ms, P=0.018) (Table 4, Fig. 2).

However, the morphology and the amplitude of the T waves were not changed and ST-segment elevation and/or depression were not found during the episodes of severe hypoglycemia (Fig. 1).

It has been suggested that prolonged QT intervals in patients with myocardial infarction may be associated with a worse prognosis [11]. The prolongation of QTc intervals is related to an increased risk of sudden death [12]. Tattersall and Gill [13] reported that the cause of sudden nocturnal death in young people with type 1 diabetes was likely to be cardiac arrhythmia induced by hypoglycemia.

Marques et al. [5] demonstrated that the degree of QTc lengthening during the episodes of hypoglycemia, which was induced by intravenous (IV) insulin, was greater compared to that during the euglycemic period in type 1 diabetic patients (median [range], 156 [8 to 258] ms vs. 6 [-3 to 28] ms; P<0.02) and in type 2 diabetic patients (median [range], 128 [16 to 166] ms vs. 4 [-3 to 169] ms; P<0.05). They suggested hypoglycemia could cause cardiac arrhythmias. They also found that a fall in plasma potassium and a rise in plasma adrenalin were greater during the episodes of insulin induced hypoglycemia [5].

Landstedt-Hallin et al. [6] reported that the mean QT interval and QT dispersion were significantly increased and serum potassium levels were significantly decreased during the episodes of insulin-induced hypoglycemia in a study conducted to thirteen patients with type 2 diabetes.

Heller conducted a study to normal adults to investigate whether the increase in both QT dispersion and QT intervals during the episodes of insulin-induced hypoglycemia could be avoided by β-blockade and the prevention of hypokalemia with IV potassium administration [7]. Many investigators have suggested that hypokalemia caused by hyperinsulinemia was a possible mechanism of altered cardiac repolarization during the episodes of hypoglycemia [14,15].

However, in this study, significant lengthening of QTc intervals during the episodes of severe hypoglycemia was observed without hypokalemia. The results of this study implied that distinct alterations in cardiac repolarization during the episodes of severe hypoglycemia might not be associated with hypokalemia.

Most of the subjects in previous studies were treated with insulin while the majority of the subjects in this study were treated with only oral glucose-lowering agents (seven out of nine patients). In addition, this study investigated the significant lengthening of the QTc interval during the episodes of severe hypoglycemia without hypokalemia in patients treated with only oral glucose-lowering agents was investigated in this study (Table 4, Fig. 2).

It has been reported that glimepiride didn't seem to have any effects on cardiac function in several studies [16-18]. Unfortunately, a comparison between insulin users and glimepiride users could not be made in this study due to the limited number of patients. Therefore, the independent effect of glimepiride on the QTc interval during the episodes of severe hypoglycemia cannot be established in this study.

Although the sympathetic activation response to hypoglycemia is known to increase heart rates [19], several studies showed no increase of heart rates during hypoglycemia and they suggested that the parasympathetic activation caused by hypoglycemia itself result in this phenomenon [20,21]. It was suggested that altered neural regulation is considered as the cause of the prolongation of QTc interval during hypoglycemia [22]. Similar to previous studies, our study did not observe tachycardia and significant differences in their heart rates during the episodes of severe hypoglycemia compared to the recovered stage in spite of all patients not taking alpha and beta adrenergic bloking agent.

We suggest that the probable mechanism of the prolonged QTc interval during severe hypoglycemia is altered autonomic regulation caused by hypoglycemia itself regardless of effects of insulin or hypokalemia.

Lindstrom et al. [23] demonstrated ST depression and the flattening of the T wave during the episodes of insulin-induced hypoglycemia in patients with type 2 diabetes. Ischemic T wave inversion and ST segment depression associated with hypoglycemia without the evidence of myocardial infarction were also previously reported [24,25]. However, in this study, ischemic changes of T wave and ST segment were not found during the episodes of severe hypoglycemia.

In summary, unlike previous studies, QTc interval prolongation in severe hypoglycemia without hypokalemia in type 2 diabetes was investigated in real-life conditions in this study. Thus, the results of this study imply that QTc interval prolongation in severe hypoglycemia may not be associated with hypokalemia but be associated with hypoglycemia itself and/or others. Most of the type 2 diabetic patients in this study were treated with only oral glucose-lowering agents and ischemic changes of ECG during the episodes of severe hypoglycemia were not found in them. Further studies with larger samples are needed to determine the mechanisms of QTc interval prolongation in severe hypoglycemia.

Figures and Tables

Fig. 1

Two representative electrocardiographic recordings of our subjects. On electrocardiograms, there did not show ischemic changes such as ST-segment abnormality and T wave inversion and did not show tachycardia during severe hypoglycemia. The comparison of corrected QT (QTc) interval between severe hypoglycemia and the recovered stage showed each (A) 432 ms versus 396 ms and (B) 442 ms versus 402 ms.

Fig. 2

Corrected QT (QTc) interval, individual values during severe hypoglycemia and the recovered stage in all subjects. Only oral glucose-lowering agents users are indicated by continuous lines, insulin users by dashed lines.

Table 1

The serum potassium and sodium levels during severe hypoglycemia and the recovered stage in all subjects

References

1. Kim JT, Oh TJ, Lee YA, Bae JH, Kim HJ, Jung HS, Cho YM, Park KS, Lim S, Jang HC, Lee HK. Increasing trend in the number of severe hypoglycemia patients in Korea. Diabetes Metab J. 2011; 35:166–172.

2. Johnson ES, Koepsell TD, Reiber G, Stergachis A, Platt R. Increasing incidence of serious hypoglycemia in insulin users. J Clin Epidemiol. 2002; 55:253–259.

3. Cryer PE, Davis SN, Shamoon H. Hypoglycemia in diabetes. Diabetes Care. 2003; 26:1902–1912.

4. Turchin A, Matheny ME, Shubina M, Scanlon JV, Greenwood B, Pendergrass ML. Hypoglycemia and clinical outcomes in patients with diabetes hospitalized in the general ward. Diabetes Care. 2009; 32:1153–1157.

5. Marques JL, George E, Peacey SR, Harris ND, Macdonald IA, Cochrane T, Heller SR. Altered ventricular repolarization during hypoglycaemia in patients with diabetes. Diabet Med. 1997; 14:648–654.

6. Landstedt-Hallin L, Englund A, Adamson U, Lins PE. Increased QT dispersion during hypoglycaemia in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus. J Intern Med. 1999; 246:299–307.

7. Heller SR. Abnormalities of the electrocardiogram during hypoglycaemia: the cause of the dead in bed syndrome? Int J Clin Pract Suppl. 2002; 27–32.

8. Desouza C, Salazar H, Cheong B, Murgo J, Fonseca V. Association of hypoglycemia and cardiac ischemia: a study based on continuous monitoring. Diabetes Care. 2003; 26:1485–1489.

9. Workgroup on Hypoglycemia, American Diabetes Association. Defining and reporting hypoglycemia in diabetes: a report from the American Diabetes Association Workgroup on Hypoglycemia. Diabetes Care. 2005; 28:1245–1249.

10. Wagner GS, Macfarlane P, Wellens H, Josephson M, Gorgels A, Mirvis DM, Pahlm O, Surawicz B, Kligfield P, Childers R, Gettes LS, Bailey JJ, Deal BJ, Hancock EW, Kors JA, Mason JW, Okin P, Rautaharju PM, van Herpen G. American Heart Association Electrocardiography and Arrhythmias Committee, Council on Clinical Cardiology. American College of Cardiology Foundation. Heart Rhythm Society. AHA/ACCF/HRS recommendations for the standardization and interpretation of the electrocardiogram: part VI: acute ischemia/infarction: a scientific statement from the American Heart Association Electrocardiography and Arrhythmias Committee, Council on Clinical Cardiology; the American College of Cardiology Foundation; and the Heart Rhythm Society. Endorsed by the International Society for Computerized Electrocardiology. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2009; 53:1003–1011.

11. Schwartz PJ, Wolf S. QT interval prolongation as predictor of sudden death in patients with myocardial infarction. Circulation. 1978; 57:1074–1077.

12. Ewing DJ, Boland O, Neilson JM, Cho CG, Clarke BF. Autonomic neuropathy, QT interval lengthening, and unexpected deaths in male diabetic patients. Diabetologia. 1991; 34:182–185.

13. Tattersall RB, Gill GV. Unexplained deaths of type 1 diabetic patients. Diabet Med. 1991; 8:49–58.

14. Laitinen T, Lyyra-Laitinen T, Huopio H, Vauhkonen I, Halonen T, Hartikainen J, Niskanen L, Laakso M. Electrocardiographic alterations during hyperinsulinemic hypoglycemia in healthy subjects. Ann Noninvasive Electrocardiol. 2008; 13:97–105.

15. Heller SR, Robinson RT. Hypoglycaemia and associated hypokalaemia in diabetes: mechanisms, clinical implications and prevention. Diabetes Obes Metab. 2000; 2:75–82.

16. Mocanu MM, Maddock HL, Baxter GF, Lawrence CL, Standen NB, Yellon DM. Glimepiride, a novel sulfonylurea, does not abolish myocardial protection afforded by either ischemic preconditioning or diazoxide. Circulation. 2001; 103:3111–3116.

17. Nieszner E, Posa I, Kocsis E, Pogatsa G, Preda I, Koltai MZ. Influence of diabetic state and that of different sulfonylureas on the size of myocardial infarction with and without ischemic preconditioning in rabbits. Exp Clin Endocrinol Diabetes. 2002; 110:212–218.

18. Rosati B, Rocchetti M, Zaza A, Wanke E. Sulfonylureas blockade of neural and cardiac HERG channels. FEBS Lett. 1998; 440:125–130.

19. Fisher BM, Gillen G, Dargie HJ, Inglis GC, Frier BM. The effects of insulin-induced hypoglycaemia on cardiovascular function in normal man: studies using radionuclide ventriculography. Diabetologia. 1987; 30:841–845.

20. Fisher BM, Gillen G, Hepburn DA, Dargie HJ, Frier BM. Cardiac responses to acute insulin-induced hypoglycemia in humans. Am J Physiol. 1990; 258(6 Pt 2):H1775–H1779.

21. Schächinger H, Port J, Brody S, Linder L, Wilhelm FH, Huber PR, Cox D, Keller U. Increased high-frequency heart rate variability during insulin-induced hypoglycaemia in healthy humans. Clin Sci (Lond). 2004; 106:583–588.

22. Lipponen JA, Kemppainen J, Karjalainen PA, Laitinen T, Mikola H, Karki T, Tarvainen MP. Dynamic estimation of cardiac repolarization characteristics during hypoglycemia in healthy and diabetic subjects. Physiol Meas. 2011; 32:649–660.

23. Lindstrom T, Jorfeldt L, Tegler L, Arnqvist HJ. Hypoglycaemia and cardiac arrhythmias in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus. Diabet Med. 1992; 9:536–541.

24. Markel A, Keidar S, Yasin K. Hypoglycaemia-induced ischaemic ECG changes. Presse Med. 1994; 23:78–79.

25. Skyrme-Jones RA, Gribbin B. Hypoglycaemia and electrocardiographic changes in a subject with diabetes mellitus. Intern Med J. 2001; 31:368–370.

PDF

PDF ePub

ePub Citation

Citation Print

Print

XML Download

XML Download