Abstract

Purpose

The purpose of this study was to investigate the effects of Wheel of Wellness counseling on wellness lifestyle, depression, and health-related quality of life in community dwelling elderly people.

Methods

A parallel, randomized controlled, open label, trial was conducted. Ninety-three elderly people in a senior welfare center were randomly assigned to two groups: 1) A Wheel of Wellness counseling intervention group (n=49) and 2) a no-treatment control group (n=44). Wheel of Wellness counseling consisted of structured, individual counseling based on the Wheel of Wellness model and provided once a week for four weeks. Wellness lifestyle, depression, and health-related quality of life were assessed pre-and post-test in both groups.

Results

Data from 89 participants were analyzed. For participants in the experimental group, there was a significant improvement on all of the wellness-lifestyle subtasks except realistic beliefs. Perceived wellness and depression significantly improved after the in the experimental group (n=43) compared to the control group (n=46) from pre- to post-test in the areas of sense of control (p=.033), nutrition (p=.017), exercise (p=.039), self-care (p<.001), stress management (p=.017), work (p=.011), perceived wellness (p=.019), and depression (p=.031). One participant in the intervention group discontinued the intervention due to hospitalization and three in the control group discontinued the sessions.

South Korea is one of the fastest-aging countries worldwide. The elderly population in Korea is expected to increase from 5.1% in 1990 to 24.3% in 2030[1]. Social issues confronting an aged society include poverty, neglect, and loss of function and roles as a result of chronic illnesses. However, health problems such as chronic diseases and/or depression, and decreased physical function are the most significant problems in the elderly population. Approximately 50% of 4,115 elderly people rated their physical health status as poor or worse, and 45% were classified as in a high-risk group for depression[2]. In fact, 5,468 elderly people (81.8 per 100,000) died from suicide in Korea, which was the highest rate among OECD countries in 2011[3]. Suicide by the elders is closely associated with a poor health condition, depression, and quality of life issues which are interrelated[45]. Thus one possible solution to the issues faced by elders may be to improve their quality of life and maintain functioning by promoting a healthy lifestyle and wellness. Although the economic impact of wellness programs is inconsistent in the literature[67], wellness programs are recognized as a strategy to reduce the health care cost borne by insurers and the government[8]. Furthermore, healthy aging has become a significant goal both to the individual and society. This raises interest in the well-being of elders in both personal and social areas in Korea.

Wellness programs have served as vehicles for weight loss, smoking cessation, nutrition, substance abuse, and stress management[79], and have been more concentrated in the workplace and schools than in areas that would impact the community-dwelling elderly. Wellness programs for the community-dwelling elderly have primarily focused on maintaining functioning level by promoting physical activity such as exercise, walking, and Tai chi[10111213].

However, wellness is intrinsically a multidimensional and synergistic construct[14]. Myers and her colleagues[15] have defined wellness as a way of life that is oriented toward optimal health and well-being in which the body, mind, and spirit are integrated so that the individual lives more fully within the human and natural community. The Wheel of Wellness is a theoretical model introduced in the early 1990s with the emergence of new wellness paradigms that were designed to complement the illness-based medical model[15]. In this model, there are five major life tasks and 12 wellness subtasks that are depicted graphically on a wheel. Those subtasks are considered directly amenable to interventions by counselors. Spirituality (life task I) is depicted in the center of the wheel, and a series of 12 self-direction subtasks (life task II) spread out like spokes from the center; the spokes regulate work and leisure (life task III), friendship (life task IV), and love (life task V), which surround the circle (see Figure 1). This holistic model was originally developed to guide counseling for enhancing wellness, and has been tested in schools, work places, and communities for over 15 years[16]. Understanding the nature of wellness is central to assessing clients, identifying wellness issues, and planning interventions. Individual wellness counseling has shown to be effective on the multidimensional wellness of law-enforcement officers, children, adolescents, midwifes, and middle-aged adults[1617].

However, wellness counseling has not been fully investigated in the elderly population. Since wellness in elders is closely related to depression and health-related quality of life[45], it is necessary to investigate the effects of wellness counseling on depression and health-related quality of life as well as wellness.

This study was a parallel, randomized controlled, open label trial. Wheel of Wellness counseling was provided once a week for one month to the experimental group. Wellness lifestyle, depression, and health-related quality of life were measured pre and post intervention in both the control and experimental groups.

The Institutional Review Board of the KNUH approved this study (IRB 2012-05-001-001). All the participants were given written information about the study's aims, benefits, and procedure and the risks of participation. They participated voluntarily after signing a written informed consent. There was no potential harm in participating; indeed, the participants' understanding of depression symptoms and the necessity of seeking professional help were enhanced. All data were kept in a secure storage.

The sampling frame included community-dwelling elderly people aged 65 years and over who were cognitively intact and who visited a senior welfare center in Deagu, South Korea. Face-to-face pre-screening excluded seniors who demonstrated impaired cognitive function as tested by the Korean version of Mini-Mental State Examination (K-MMSE <24)[18] and those who were 64 years of age or younger. The senior welfare center has more than 3,000 members and operates various educational and recreational programs (e.g., yoga, dancing, and singing academies etc.) without an additional charge. The sample size was determined for the primary outcomes with a two-tailed t-test assuming power ≥.80, α=.05, and a modest effect size of .39[19]. It was calculated using G*Power 3.1.7 software[20]. Based on these assumptions, the target recruitment sample size was 41 participants per group (intervention and control).

Prior to the randomization process, we constructed a contact list of the sample pool because the welfare center's registration list was confidential. We introduced the study to the seniors face-to-face and asked permission to call them in order to invite participation in the study. Posters advertising the study were placed in the main lobby of the senior welfare center from July 23 to July 27, 2012. A total of 498 seniors (196 man and 302 women) signed up as potential participants and received the screening test (the K-MMSE) for cognitive function. Two seniors who showed cognitive impairment (a K-MMSE score below 24) were excluded. The remaining sample was stratified by gender. Then the names on each of the female and male sampling list were erased for allocation concealment. The randomization process was accomplished by a research assistant who was not directly involved in the data-collection process. Considering a 50% of refusal rate, 37 female and 24 male seniors were randomly selected for the experimental and control groups respectively from the separate female and male sampling lists by using a random digits table (a total of 122 seniors).

Then, the research assistant made an invitation to call the seniors who were selected for the study. Of the 122 seniors, 44 and 49 seniors in the experimental and control groups, respectively, were enrolled in the study (refusal rate: 23.8%). Moreover, 89 of the 93 participants completed the study (drop-out rate: 4.3%). Drop-out reasons included hospitalization (n=2), refusal (n=1), and moving to another city (n=1) (see Figure 2). The research measures were administered to the participants prior to and immediately following the 4-week intervention period. The Wheel of Wellness counseling was conducted from August 20, 2012 to October 5, 2012.

The Wheel of Wellness model and counseling methods proposed by Myers and her colleagues[21] was adopted for this study. Two doctoral- and two masters-level nurses were trained to provide Wheel of Wellness counseling. To maximize fidelity, these four nurses were given the counselor's program manual and a one-day training session prior to the study's start. These outlined the purpose and process of the study, concepts of the Wheel of Wellness model, counseling technique and tools, education materials for nutrition and exercise, and measures. Once the study began, the author communicated with the counselors and coached them via an online chat room as needed and a weekly case conference to ensure the quality and homogeneity of the counseling.

Wheel of Wellness counseling was conducted individually once a week for four weeks in a private room at the senior center. Each counseling session lasted approximately one hour. The nurses made a phone call to arrange appointments and follow-up on the participants between sessions. The counseling proceeded in four steps: 1) introduction of the Wheel of Wellness model; 2) assessing and identifying multidimensional wellness issues using the wellness lifestyle profile; 3) intentional intervention, including setting a personal wellness goal and plan to enhance wellness in selected subtasks of the wheel; and 4) evaluation, follow-up, and support for wellness-plan retention. All the participants were given their personal wellness portfolios containing a wellness profile diagram which was an analysis of the Wellness Evaluation of Lifestyle (WEL) test findings, at the first session. The nurses provided individual counseling and education to enhance the seniors' wellness based on their portfolios. A community network designed to enhance well-being was also constructed. The nurses referred participants to a community mental health clinic for depressed seniors and to physical activity and/or social networking programs run by a senior center in order to enhance specific subtasks of the wheel.

Demographic characteristics included gender, age, education level, living state, marital status, religion, occupation, and monthly income. In addition, the intervention group was asked six questions regarding program satisfaction.

The Wellness Evaluation of Lifestyle (WEL), which was developed and revised over a 20-year period, is an assessment instrument based on the Wheel of Wellness model[21]. The purpose of the WEL is to help respondents make healthy lifestyle choices based on their response to each of the five life tasks and subtasks. This instrument measures healthy lifestyle alongside counseling for health promotion and consists of 131 self-statements to which participants respond on a five-point Likert scale. The five major life tasks include spirituality, self-direction, work and leisure, friendship, and love. The self-direction task in this study consisted of 12 subtasks: sense of worth, sense of control, realistic beliefs, emotional responsiveness, intellectual stimulation, sense of humor, nutrition, exercise, self-care, stress management, gender identity, and cultural identity. The cultural identity subtask was designed for the cultural minority and was eliminated from this study because it was not appropriate to the Korean elders.

Each subtask score was converted into a standard score that ranged from 0 to 100. Higher scores indicate a better wellness status. Before adopting the WEL, we purchased a license from Mind Garden, which holds the copyright of the WEL. Since there is no Korean version of the WEL, the author translated it into Korean. The translated WEL was back-translated by a bilingual and bicultural nursing researcher, and was then reviewed by five colleges and three elderly people without any health-education background to assure feasibility. Some items were reworded in colloquial style to make it easy to understand. Cronbach's α for the WEL was 0.92 with the Korean participants in this study.

Depression was measured using the PHQ-9K[22]. The PHQ-9K is a tool that was developed by translating the PHQ-9 (Patient Health Questionnaire-Nine) developed by Kroenke et al.[23] into Korean. Permission to use the PHQ-9K was obtained from the developer, PaJa Lee Donnelly, by e-mail. The PHQ-9K items assess somatic symptoms, including affective, cognitive aspects, and functional categories, unlike most current Korean depression instruments. It consists of nine items assessed on a 0-to-3 point scale (0="not at all," 1="several days," 2="more than half of the days," and 3="nearly every day"); the total score ranges from 0 to 27 and higher scores indicate more severe depression. Participants with a PHQ-9K score less than 4 may not need depression treatment, those with a score between 5 and 14 may require treatment based on the duration of symptoms and functional impairment, and those with a score above 15 definitely require treatment. Cronbach's α for the original tool was 0.92[22]. Cronbach's α for the PHQ-9K was 0.81 for the Korean participants, demonstrating reliability.

In this study, we used the Short Form (SF-8™) Health Survey developed by Quality Metric Incorporated to measure health-related quality of life. The SF-8™ is a generic health survey that can be used across ages, diseases, and treatment groups, and has been widely used in Korea. Before adopting the SF-8, we purchased the license from the copyright holder, Optum Incorporated. This instrument consists of eight self-administered items using a five-point Likert scale. Each item assesses a different dimension of health: general health (GH), physical functioning (PF), role physical (RP), bodily pain (BP), vitality (VT), social functioning (SF), mental health (MH), and role emotional (RE). The subscale, physical-component-summary (PCS), and mental-component-summary (MCS) scores were calculated using SFS scoring software provided by Quality Metric. A score ranging from 0 to 100 is calculated for each subscale, and higher scores indicate better HRQOL. Cronbach's α for the SF-8™ was 0.82 in this study.

The data were analyzed using SPSS version 19.0 (SPSS, Inc., an IBM Company, Chicago, Illinois, U.S.A.). In addition to the descriptive analysis, differences between the control and experimental groups were assessed by two-tailed χ2-tests, t-tests, or the Wilcoxon rank-sum test, depending on the distribution of the data. Comparisons of wellness lifestyle, depression, and quality of life between the control and experimental groups were assessed by t-test or the Wilcoxon rank-sum test, depending on the results of the Kolmogorov-Smirnov test for normality. Analysis of covariance (ANCOVA) was used to adjust for preexisting differences in nonequivalent groups.

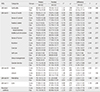

There were no significant differences in socio-demographic characteristics between the experimental and control groups prior to the intervention (see Table 1). The mean age of the participants was 71.35 years (SD=4.61). At the beginning of the study, the experimental and control groups did not significantly differ on their standardized scores from the PHQ-9K, SF-8™, and WEL subtasks with the exception of the "self-care" subtask (see Table 1). The control group demonstrated a significantly higher self-care level than experimental group at baseline (t= -2.09, p=.005).

After Wheel of Wellness counseling, participants in the experimental group showed significant improvement on all the wellness lifestyle subtasks except realistic beliefs. The experimental group had significant improvement following the intervention in sense of control (t=2.16, p=.033), nutrition (t=2.44, p=.017), exercise (t=2.10, p=.039), self-care (F=15.31, p<.001), stress management (t=2.43, p=.017), work (t=2.60, p=.011), and perceived wellness (t=2.39, p=.019) compared to the control group (see Table 2). The participants in the experimental group had significant improvement on depression after Wheel of Wellness counseling (t= -2.54, p=.011) and in the difference between the pre- and post-tests compared to the control group (z= -2.15, p=.031). However, there were no significant changes in both the physical component scale (t=1.61, p=.111) and the mental component scale (t= -0.03, p=.974) of quality of life (see Table 3).

Although a construction of the Wheel of Wellness model has been examined and implications for counseling have been suggested[2425], there have not been any randomized, controlled trials to test the effects of the model. Moreover, Wheel of Wellness counseling has been primarily conducted by psychologists. The results of this randomized controlled trial demonstrated that Wheel of Wellness counseling provided by registered nurses was beneficial in enhancing wellness of the community-dwelling elderly. The dropout rate (4.3%) was very low, and participants' satisfaction was high, which indicates that the intervention was acceptable and feasible to the participants. Attendance at the weekly intervention sessions was generally high which strengthened the study's internal validity along with low dropout rate.

Among the wellness-lifestyle subtasks, 'realistic beliefs' was ranked the lowest in both the control and experimental groups and did not improve after Wheel of Wellness counseling. The realistic beliefs subtask asked if the individual accepted him-/herself as imperfect and included the following examples: 1) "I'm often disappointed because my expectations are not met"; 2) "It is important for me to be liked or loved by almost everyone I meet"; and 3) "I must be competent, adequate, and achieving in most things to consider myself worthwhile." This was an interesting finding because it may reflect the Korean culture. The Korean culture has an inclination toward perfectionism, which makes people treat themselves in an overly strict manner in order to meet high expectations[26]. Unrealistic beliefs and expectations of oneself may be related to depression, anxiety, and/or poor mental health[27]. It was quite challenging to try to change long-lasting beliefs in this study. Strategies to facilitate realistic beliefs need to be developed.

Depression improved significantly after Wheel of Wellness counseling in this study. However, there was no significant change in health related quality of life for either the control or the experimental group. Health related quality of life is known to be affected by exercise, depression, activities of daily living, and social support[2829]. The lack of significant change in this study could be attributed to the choice of outcome measure. The SF-8™ contains eight items, and each of them measures distinct health domains. Among items of the SF-8™, 5 were asking about the respondent's functioning level. In this study, the majority of participants indicated little or no problems with most of the functional domains from the baseline. Therefore, the SF-8™ might not have been sensitive enough for this study.

We utilized community resources based on the participants' wellness profiles. Although there were various programs available in the senior welfare centers and the public health centers that might enhance certain wellness areas, there was no service available to integrate these resources. Wheel of Wellness counseling, however, is a comprehensive, holistic approach to effectively enhance personal wellness. Wheel of Wellness counseling encouraged participants to identify their weakness in the wellness areas, to set individually tailored wellness goals and plans weekly, and to facilitate utilization of community resources. This comprehensive approach of Wheel of Wellness counseling could have contributed to the increase of wellness life style. The attributes of the concept of empowerment in older adults include active participation, informed change, knowledge to problem solve, self-care responsibility, presence of client competency, and control of health or life[30]. Wheel of Wellness counseling appears to empower the participants. The participants were encouraged to actively participate by setting personal wellness goal and making a commitment to changes in lifestyles during the first session. Then, they were provided information and resources to enhance their wellness. Most of participants in the study were taking 2 to 5 classes a week at the senior welfare center. However, accessible resources for the study might differ as it depends on which senior welfare centers were elected. Although most of senior welfare centers offer quite similar programs, this may weaken the study's external validity.

The counselors in the study were experienced nurses. After completing wellness counseling training, they were able to evaluate participants' wellness lifestyle and to provided education and counseling. The nurses demonstrated their competencies especially in health related subtasks including nutrition, selfcare, and stress management. Although perceived overall wellness significantly improved in the study, the effects on certain life tasks, such as spirituality, friendship, and love, could not be shown. As personal counseling may be affected by the counselor's competency, this result may indicate that the nurse counselors were more competent in the areas of physical and mental health than spirituality and relationships. Therefore, the counselor's manual and training program to empower nurses' competency as wellness counselors needs to be improved, especially in the area of spirituality. The results of this study suggest expanding the role for nurses, especially in community health, because nurses are at the front line of health promotion and wellness enhancement.

A potential limitation of this study is that we analyzed the mean scores from the 17 subtasks to test the effects of the intervention rather than the five factors suggested by the Individual Self-Wellness (IS-Wel) model[24]. In addition, the participants who accepted the invitation to participate may differ from the general population at the senior center in terms of motivation. Finally, the participants were not blind to their group assignments; thus, the possibility of Hawthorne or other non-specific effects could not be entirely excluded. The control group might have baeen exposed to some of the information because the participants in the experimental and control group were able to contact each other. However, Wheel of Wellness counseling is provided individually based on the personal wellness profile. Therefore, the effects of contamination would be limited even considering the possibility that participants in the experimental group meet and told participants in the control group about the counseling.

The findings of the current study indicate that Wheel of Wellness counseling was significantly effective in enhancing wellness lifestyle, perceived wellness, and depression in community-dwelling elders. In addition, it showed that Wheel of Wellness counseling could be a powerful measure for nurses in the areas of community health and health promotion. Thus, the results of this study encourage use of Wheel of Wellness counseling in nursing practice. Long term follow-up studies are recommended to investigate whether these effects are maintained after the intervention ends. Also further research is needed to determine the effectiveness and feasibility of Wheel of Wellness counseling in various settings and for other populations.

Figures and Tables

Table 1

Homogeneity Test of Socio-demographic Characteristics, WEL, Depression and Quality of Life between Groups

References

1. Kim H, Traphagan JW. From socially weak to potential consumer: Changing discourses on elder status in South Korea. Care Manag J. 2009; 10(1):32–39.

2. Lee MS. Structures of health inequalities of Korean elderly: Analysis of Korean longitudinal study of ageing. Health Soc Sci. 2009; 25:5–32.

3. Statistics Korea. 2012 annual report on the causes of death statistics [Internet]. Daejeon: Author;2013. cited 2014 January 20. Available from: http://kostat.go.kr/portal/korea/kor_nw/2/6/2/index.board?bmode=read&bSeq=&aSeq=308559&pageNo=1&rowNum=10&navCount=10&currPg=&sTarget=title&sTxt=.

4. Helliwell JF, Putnam RD. The social context of well-being. Philos Trans R Soc Lond B Biol Sci. 2004; 359(1449):1435–1446. DOI: 10.1098/rstb.2004.1522.

5. Shin KM, Cho SM, Hong CH, Park KS, Shin YM, Lim KY, et al. Suicide among the elderly and associated factors in South Korea. Aging Ment Health. 2013; 17(1):109–114.

6. Lerner D, Rodday AM, Cohen JT, Rogers WH. A systematic review of the evidence concerning the economic impact of employee-focused health promotion and wellness programs. J Occup Environ Med. 2013; 55(2):209–222. DOI: 10.1097/JOM.0b013e3182728d3c.

7. Phillips JF. Using an ounce of prevention: Does it reduce health care expenditures and reap pounds of profits? A study of the financial impact of wellness and health risk screening programs. J Health Care Finance. 2009; 36(2):1–12.

8. Boston RB, Clifford BM. Laws affecting wellness programs and some things they make you do. Employee Relat Law J. 2013; 39(1):30–34.

9. Avery G, Johnson T, Cousins M, Hamilton B. The school wellness nurse: A model for bridging gaps in school wellness programs. Pediatr Nurs. 2013; 39(1):13–18.

10. Chen IJ, Chou CL, Yu S, Cheng SP. Health services utilization and cost utility analysis of a walking program for residential community elderly. Nurs Econ. 2008; 26(4):263–269.

11. Lee TW, Ko IS, Lee KJ. Health promotion behaviors and quality of life among community-dwelling elderly in Korea: A cross-sectional survey. Int J Nurs Stud. 2006; 43(3):293–300. DOI: 10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2005.06.009.

12. Choi CY, Cho HC. The effect of degree of senior exercise participation on wellness. J Korea Soc Wellness. 2012; 7(3):13–21.

13. Hatch J, Lusardi MM. Impact of participation in a wellness program on functional status and falls among aging adults in an assisted living setting. J Geriatr Phys Ther. 2010; 33(2):71–77.

14. Roscoe LJ. Wellness: A review of theory and measurement for counselors. J Couns Dev. 2009; 87(2):216–226.

15. Myers JE, Sweeney TJ, Witmer M. The wheel of wellness counseling for wellness: A holistic model for treatment planning. J Couns Dev. 2000; 78(3):251–266.

16. Myers JE, Sweeney TJ. Wellness counseling: The evidence base for practice. J Couns Dev. 2008; 86(4):482–493. DOI: 10.1002/j.1556-6678.2008.tb00536.x.

17. Tanigoshi H, Kontos AP, Remley TP Jr. The effectiveness of individual wellness counseling on the wellness of law enforcement officers. J Couns Dev. 2011; 86(1):64–74. DOI: 10.1002/j.1556-6678.2008.tb00627.x.

18. Kang Y, Na DL, Hahn S. A validity study on the Korean minimental state examination (K-MMSE) in dementia patients. J Korean Neurol Assoc. 1997; 15(2):300–308.

19. Cohen J. Statistical power analysis for the behavioral sciences. 2nd ed. Hillsdale, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates;1988.

20. Faul F, Erdfelder E, Lang AG, Buchner A. G*Power 3: A flexible statistical power analysis program for the social, behavioral, and biomedical sciences. Behav Res Methods. 2007; 39(2):175–191.

21. Myers JE, Sweeney TJ. Counseling for wellness: Theory, research, and practice. Alexandria, VA: American Counseling Association;1998.

22. Donnelly PL, Kim KS. The patient health questionnaire (PHQ-9K) to screen for depressive disorders among immigrant Korean American elderly. J Cult Divers. 2008; 15(1):24–29.

23. Kroenke K, Spitzer RL, Williams JB. The PHQ-9: Validity of a brief depression severity measure. J Gen Intern Med. 2001; 16(9):606–613.

24. Hattie JA, Myers JE, Sweeney TJ. A factor structure of wellness: Theory, assessment, analysis, and practice. J Couns Dev. 2004; 82(3):354–364. DOI: 10.1002/j.1556-6678.2004.tb00321.x.

25. Villalba JA, Myers JE. Effectiveness of wellness-based classroom guidance in elementary school settings: A pilot study. J Sch Couns. 2008; 6(9):1–31.

26. Lee DG, Park HJ. Cross-cultural validity of the frost multidimensional perfectionism scale in Korea. Couns Psychol. 2011; 39(2):320–345. DOI: 10.1177/0011000010365910.

27. Ashbaugh A, Antony MM, Liss A, Summerfeldt LJ, McCabe RE, Swinson RP. Changes in perfectionism following cognitive-behavioral treatment for social phobia. Depress Anxiety. 2007; 24(3):169–177. DOI: 10.1002/da.20219.

28. Clifford A, Rahardjo TB, Bandelow S, Hogervorst E. A cross-sectional study of physical activity and health-related quality of life in an elderly Indonesian cohort. Br J Occup Ther. 2014; 77(9):451–456. DOI: 10.4276/030802214X14098207541036.

29. Kim JI. Levels of health-related quality of life (EQ-5D) and its related factors among vulnerable elders receiving home visiting health care services in some rural areas. J Korean Acad Community Health Nurs. 2013; 24(1):99–109. DOI: 10.12799/jkachn.2013.24.1.99.

30. Fotoukian Z, Shahboulaghi FM, Khoshknab MF, Mohammadi E. Concept analysis of empowerment in old people with chronic diseases using a hybrid model. Asian Nurs Res (Korean Soc Nurs Sci). 2014; 8(2):118–127. DOI: 10.1016/j.anr.2014.04.002.

PDF

PDF ePub

ePub Citation

Citation Print

Print

XML Download

XML Download