MATERIALS AND METHODS

Patients

This retrospective study was approved by an Institutional Review Board and written informed consent was waived. In a search of a medical database, the researchers identified 159 patients, who had undergone Whipple surgery at our institution (Pusan National University Hospital [PNUH]) from January 1997 to December 2014. Among the patients, eight who did not undergo contrast-enhanced abdominal CT were excluded. Thus, the final study group consisted of 151 patients (92 men and 59 women; mean age, 62.9 years; range, 23–85 years).

The patients with late hemorrhage were defined according to grade C PPH, proposed by the ISGPS in 2007 (

4). This study included 16 patients who had a vascular abnormality diagnosed by angiography, and four patients who had undergone endoscopic hemostasis or died due to massive bleeding among the patients received a packed red blood cell transfusion > 24 hours after Whipple operation. Patients who recovered by conservative management and transfusion were not included in the bleeding group. Finally, 20 patients (16 men and 4 women; mean age, 65.7 years; range, 47–79 years) who had late hemorrhage, after the Whipple operation were included in the bleeding group.

CT Technique

A CT examination was performed using a 128-detector row scanner (Somatom Definition AS+; Siemens Medical System, Erlangen, Germany; n = 133), a 16-detector row scanner (Somatom Sensation 16; Siemens Medical System; n = 9) or a four-detector row scanner (LightSpeed QX/I; GE Medical System, Milwaukee, WI, USA; n = 9).

The CT techniques varied because of the retrospective nature of this particular study. Most patients (n = 146) underwent a three-phase dynamic CT including arterial phase, portal venous phase, and delayed phase, and the remaining five patients underwent a two-phase or singlephase CT.

For all patients, a total volume of 120 mL of nonionic contrast material containing 370 mgI/mL of iodine (iopromide, Ultravist 370; Bayer Healthcare, Berlin, Germany) was administered intravenously at a rate of 3.0 mL/s, using an automated injector device through an 18-gauge intravenous catheter located in the antecubital vein. No oral contrast material was administered in the CT protocol. The scan delay time was determined using the bolus-tracking technique (CARE-Bolus Software; Siemens Medical Systems).

To obtain time-attenuation curves, a small region of interest was placed over the abdominal aorta. The arterial phase scanning was automatically initiated at 15 seconds, after a level of contrast enhancement of the aorta reached a certain preferred point (100 Hounsfield unit [HU]). The portal venous phase scanning sequence was obtained 10 seconds, after completion of arterial phase. The delayed phase scanning was obtained 75 seconds, after completion of portal venous phase. CT scans were obtained with the patient in a supine position during a single breath-hold.

CT parameters for Somatom Definition AS+ included a detector collimation, 0.6 mm, table pitch 0.8; an effective slice thickness, 4 mm; reconstruction intervals, 4 mm; 120 kVp; 200 mAs. CT parameters for Somatom Sensation 16 included a detector collimation, 0.75 mm; table feed, 9 mm per rotation; table pitch, 1.25; an effective slice thickness, 4 mm; reconstruction intervals, 4 mm; 120 kVp; 200 mAs.

The CT parameters for the LightSpeed QX/i scanner were as follows: detector collimation, 1.25 mm; table feed, 7.5 mm per rotation; table pitch, 3.0; effective slice thickness, 5 mm; reconstruction intervals, 5 mm; 120 kVp; 230 mAs.

Each of the contrast-enhanced CT image data were directly interfaced to a picture archiving and communication system workstation (PACS system; M-view, Marotec, Seoul, Korea), which displayed all image data on monitors (two monitors, 2048–2560 image matrices, 10-bit viewable grayscale, and 145.9-ft lambert luminescence).

CT Analysis

CT scans of 151 patients were reviewed by the two abdominal radiologists (with 20 and 6 years of clinical experience with abdominal CT interpretation, respectively), who were blinded to the information regarding the presence or absence of late bleeding in the patients. Disagreements were ultimately resolved by consensus. Both readers retrospectively reviewed the initial postoperative followup CT images (mean, 8.2 days; range, 2–174 days) for any presence of fluid in the abdominal and pelvic cavities and their densities, fluid along the hepaticojejunostomy (HJ), and pancreaticojejunostomy (PJ). Peritoneal free fluid density > 20 HU was considered a hemoperitoneum. Among fluid collections, the researchers evaluated the presence of air at fluid along PJ and assumed it to be a pancreatic fistula. An abscess was defined as an abnormal fluid collection with a visible enhancing rim or gas. The readers also measured the diameter of the visible gastroduodenal artery (GDA) stump in any plane with maximum caliber.

Clinical Data Collection

The medical records of 151 patients were reviewed using several factors including age, sex, the presence of hypertension, and diabetes mellitus (DM). The reason for Whipple surgery (malignant or benign) and the size of the lesion recorded on the pathology report were also assessed. Laboratory data, which included serum C-reactive protein, amylase, lipase, and total cholesterol levels were reviewed and recorded by one radiologist, who did not participate as a reader. Serum biochemical test results were only recorded if performed within 3 days of the early postoperative CT scan. In addition, peritoneal fluid analysis results, including color, polymorphonuclear leukocytes (PMN) count, and amylase level, were evaluated to assess for infected fluid or the leakage of pancreatic juice. A PMN count > 250 cells/µL was considered infected fluid and an amylase level > 100 U/L was considered a pancreatic leak (

9).

Statistical Analysis

The above-mentioned CT findings, measured vascular structure values, and clinical parameters of the 20 patients with hemorrhage were compared with those of the 131 patients without late hemorrhage, using univariate logistic regression analysis. The researchers selected potential candidates for inclusion in multivariate logistic regression analysis to evaluate independent predictors of the late PPH.

The cut-off size of the GDA stump for distinguishing the bleeding from the non-bleeding group was estimated by the area under the receiver operating characteristics curve (AUC). An intraclass correlation coefficient (ICC) and kappa test were used to assess the interobserver agreement. The levels of agreement for ICC were 0.91–1.00, excellent; 0.81–0.90, very good; and 0.71–0.80, good. The levels of agreement for kappa value were 0.81–1.00, excellent; 0.61–0.80, good; 0.41–0.60, moderate; 0.21–0.40, fair; and less than 0.20, poor. All statistical analyses were made by running SPSS for Windows (ver. 22.0; IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, USA) on a personal computer. Two-tailed p values less than 0.05 were considered statistically significant.

Go to :

RESULTS

Twenty patients (13.2%) developed a late hemorrhage due to an abnormality in the GDA stump (n = 12), common hepatic artery (CHA) (n = 2), or proper hepatic artery (n = 2) or an active ulcer at the gastrojejunal or duodenojejunal anastomosis site (n = 4). The mean period between surgery and late bleeding was 23 days (range, 6–46 days).

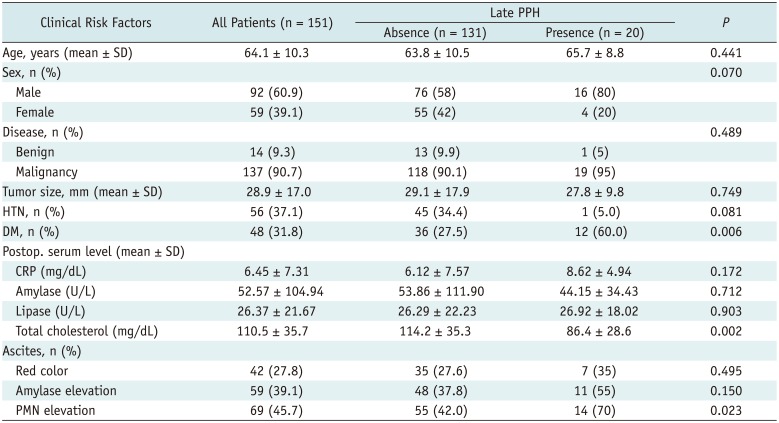

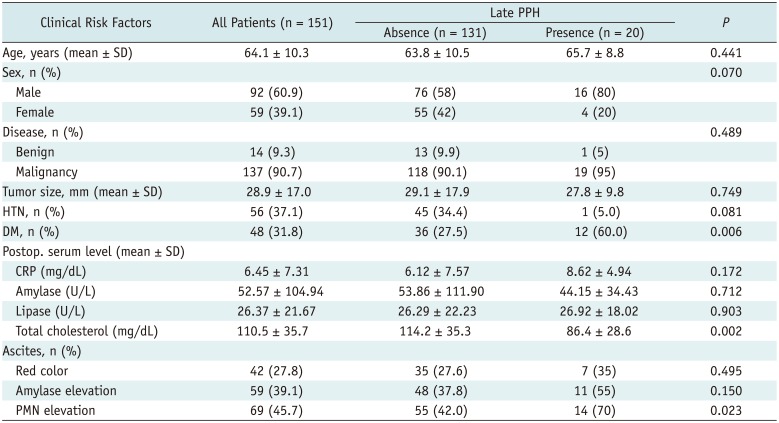

Table 1 summarizes the univariate analysis results for all the clinical characteristics of the patients with or without hemorrhage. There were no differences in age, sex, underlying hypertension, presence versus absence of malignant tumors, lesion size, or postoperative serum and peritoneal fluid laboratory findings present between the patients with and those without late hemorrhage, except for DM, cholesterol levels, and the presence of infected peritoneal fluid.

Table 1

Univariate Analysis of Clinical Characteristics for Patients with or without Late PPH

|

Clinical Risk Factors |

All Patients (n = 151) |

Late PPH |

P

|

|

Absence (n = 131) |

Presence (n = 20) |

|

Age, years (mean ± SD) |

64.1 ± 10.3 |

63.8 ± 10.5 |

65.7 ± 8.8 |

0.441 |

|

Sex, n (%) |

|

|

|

0.070 |

|

Male |

92 (60.9) |

76 (58) |

16 (80) |

|

|

Female |

59 (39.1) |

55 (42) |

4 (20) |

|

|

Disease, n (%) |

|

|

|

0.489 |

|

Benign |

14 (9.3) |

13 (9.9) |

1 (5) |

|

|

Malignancy |

137 (90.7) |

118 (90.1) |

19 (95) |

|

|

Tumor size, mm (mean ± SD) |

28.9 ± 17.0 |

29.1 ± 17.9 |

27.8 ± 9.8 |

0.749 |

|

HTN, n (%) |

56 (37.1) |

45 (34.4) |

1 (5.0) |

0.081 |

|

DM, n (%) |

48 (31.8) |

36 (27.5) |

12 (60.0) |

0.006 |

|

Postop. serum level (mean ± SD) |

|

|

|

|

|

CRP (mg/dL) |

6.45 ± 7.31 |

6.12 ± 7.57 |

8.62 ± 4.94 |

0.172 |

|

Amylase (U/L) |

52.57 ± 104.94 |

53.86 ± 111.90 |

44.15 ± 34.43 |

0.712 |

|

Lipase (U/L) |

26.37 ± 21.67 |

26.29 ± 22.23 |

26.92 ± 18.02 |

0.903 |

|

Total cholesterol (mg/dL) |

110.5 ± 35.7 |

114.2 ± 35.3 |

86.4 ± 28.6 |

0.002 |

|

Ascites, n (%) |

|

|

|

|

|

Red color |

42 (27.8) |

35 (27.6) |

7 (35) |

0.495 |

|

Amylase elevation |

59 (39.1) |

48 (37.8) |

11 (55) |

0.150 |

|

PMN elevation |

69 (45.7) |

55 (42.0) |

14 (70) |

0.023 |

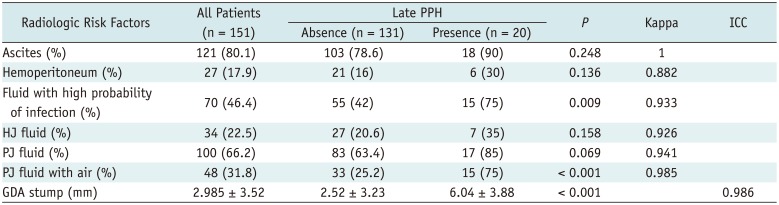

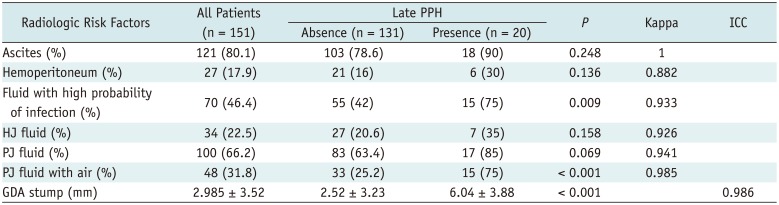

Table 2 shows a comparison of the CT features between the bleeding and non-bleeding groups during the postoperative periods. Observed features in CT showed excellent interobserver agreements (kappa = 0.882–1.000, ICC = 0.986).

Table 2

Univariate Analysis of Postoperative CT Findings for Patients with or without Late PPH

|

Radiologic Risk Factors |

All Patients (n = 151) |

Late PPH |

P

|

Kappa |

ICC |

|

Absence (n = 131) |

Presence (n = 20) |

|

Ascites (%) |

121 (80.1) |

103 (78.6) |

18 (90) |

0.248 |

1 |

|

|

Hemoperitoneum (%) |

27 (17.9) |

21 (16) |

6 (30) |

0.136 |

0.882 |

|

|

Fluid with high probability of infection (%) |

70 (46.4) |

55 (42) |

15 (75) |

0.009 |

0.933 |

|

|

HJ fluid (%) |

34 (22.5) |

27 (20.6) |

7 (35) |

0.158 |

0.926 |

|

|

PJ fluid (%) |

100 (66.2) |

83 (63.4) |

17 (85) |

0.069 |

0.941 |

|

|

PJ fluid with air (%) |

48 (31.8) |

33 (25.2) |

15 (75) |

< 0.001 |

0.985 |

|

|

GDA stump (mm) |

2.985 ± 3.52 |

2.52 ± 3.23 |

6.04 ± 3.88 |

< 0.001 |

|

0.986 |

Forty-eight (31.8%) patients showed PJ fluid with air on postoperative CT, and 70 (46.4%) had fluid with enhancing rim or gas on postoperative CT. The CT findings of pancreatic fistula and abscess were significantly related to late bleeding (p < 0.001 and p = 0.009, respectively). The size of the GDA stump was significantly greater in the bleeding compared with that of the no-bleeding group (mean ± standard deviation, 6.04 ± 3.88 mm vs. 2.52 ± 3.23 mm). The cut-off value for the GDA stump size to distinguish the bleeding from the non-bleeding groups was 4.45 mm (sensitivity 70% and specificity 68%, AUC = 0.748, p < 0.001). A GDA stump > 4.45 mm on the 1-week postoperative CT was a significant risk factor for predicting late PPH in the univariate analysis (odds ratio, 4.944; p = 0.002). Other postoperative CT findings, including ascites, hemoperitoneum, and fluid along the HJ or PJ were not predictive of a late hemorrhage.

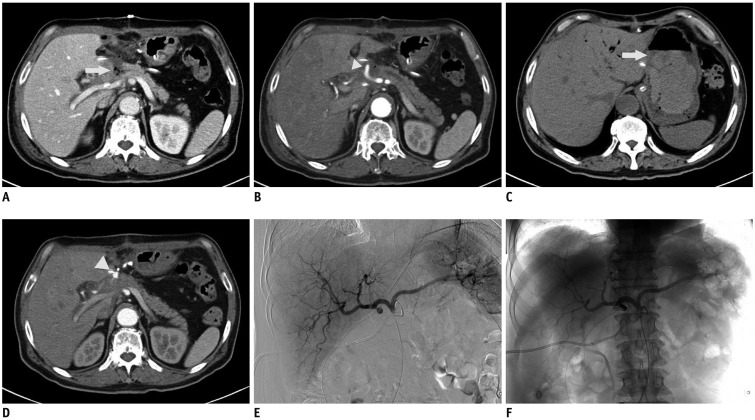

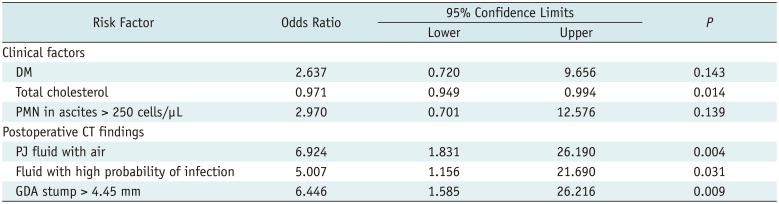

The multivariate logistic regression analysis results for the risk factors in the patients with or without late hemorrhage are shown in

Table 3. The presence of radiological features of PJ fluid with air and abscess, and a GDA stump > 4.45 mm were associated with late hemorrhage (

p = 0.004,

p = 0.031,

p = 0.009, respectively) (

Fig. 1).

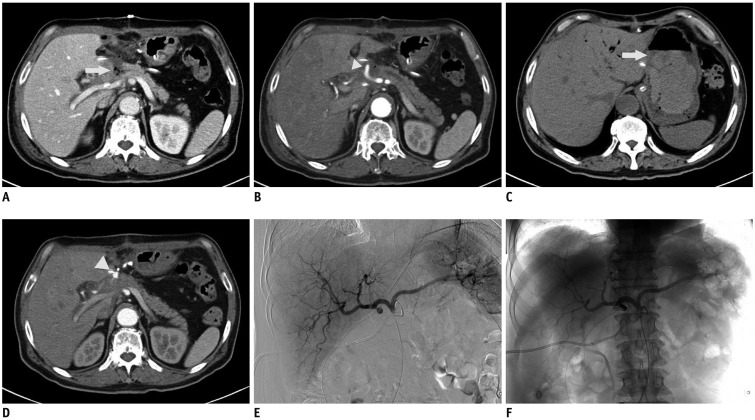

| Fig. 1

67-year-old male who had undergone Whipple procedure for pancreatic head cancer.

A, B. Contrast-enhanced CT performed at postoperative day 7. Axial portal venous-phase CT shows fluid with air bubble around pancreaticojejunostomy (arrow) (A), suggestive of pancreatic leakage and arterial phase CT shows 10 mm-sized GDA stump (arrowhead) (B). C-F. CT and DSA performed at postoperative day 26. Non-enhanced CT shows intraluminal sentinel clot sign in stomach (arrow) (C) and arterialphase CT shows pseudoaneurysm of GDA stump (arrowhead) (D). DSA shows stump pseudoaneursym as in CT (E) and coil embolization is done successfully (F). DSA = digital subtraction angiography, GDA = gastroduodenal artery

|

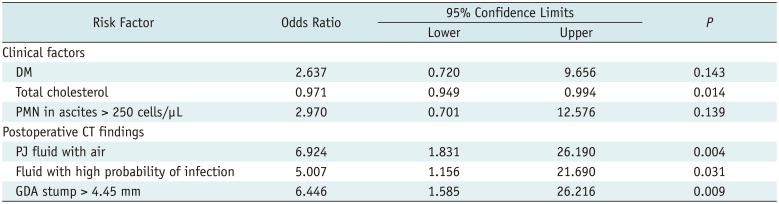

Table 3

Multivariate Logistic Regression Analysis of Risk Factors in Patients with or without Late PPH

|

Risk Factor |

Odds Ratio |

95% Confidence Limits |

P

|

|

Lower |

Upper |

|

Clinical factors |

|

|

|

|

|

DM |

2.637 |

0.720 |

9.656 |

0.143 |

|

Total cholesterol |

0.971 |

0.949 |

0.994 |

0.014 |

|

PMN in ascites > 250 cells/µL |

2.970 |

0.701 |

12.576 |

0.139 |

|

Postoperative CT findings |

|

|

|

|

|

PJ fluid with air |

6.924 |

1.831 |

26.190 |

0.004 |

|

Fluid with high probability of infection |

5.007 |

1.156 |

21.690 |

0.031 |

|

GDA stump > 4.45 mm |

6.446 |

1.585 |

26.216 |

0.009 |

The presence of DM and suspected infection in the peritoneal fluid, which were clinically significant factors in the univariate analysis, were not observed as significant risk factors for the late hemorrhage in the multivariate analysis. A lower serum cholesterol level was associated with late PPH in the multivariate analysis (p = 0.014).

Go to :

DISCUSSION

Diseases of the pancreas can vary and include tumors as well as acute and chronic pancreatitis. Treatment options for pancreatic disease also vary, but surgery is the only curative method for pancreatic adenocarcinoma, other miscellaneous malignancies, or medically intractable chronic pancreatitis. Pancreatoduodenectomy, or the so-called Whipple procedure, consists of resecting the pancreatic head, duodenum, short segment of the jejunum and the gastric antrum, followed by PJ, HJ, and gastrojejunostomy or duodenojejunostomy (

10). Various complications can occur after pancreatoduodenectomy, including delayed gastric emptying (50%) (

11), pancreatic fistula (18%) (

12), wound infection, abdominal abscess, intra-abdominal bleeding, and anastomotic leakage. Postoperative intra-abdominal bleeding is a relatively rare complication, but has a high mortality rate (

3).

In 2007, the ISGPS categorized PPH based on time of onset and severity (

4). The causes of early PPH are most likely due to the technical failure of the appropriate hemostasis or an underlying perioperative coagulopathy. Most cases of PPH are caused by complications that appear 24 hours after surgery (e.g., peripancreatic vascular erosion secondary to intra-abdominal contamination of enteric, pancreatic, or bile juice from a leaking anastomosis, an inflammatory process that is caused by local infection or abscess in the intra-abdominal cavity, an intra-abdominal drain or ulceration at the site of an anastomosis, or the development of an arterial pseudoaneurysm) (

1314). Among them, an abnormality in the GDA stump (either a pseudoaneurysm or active extravasation) is the most common cause of late PPH (

715) as in this study.

The radiological findings of PPH due to various causes are well-known, including sentinel clot sign, hemoperitoneum, pseudoaneurysm, and active extravasation of contrast material (

716). A patient's symptoms, such as melena or hematemesis, sentinel bleeding from an abdominal drain, or a decreased hemoglobin level, can be detected when clinically significant bleeding occurs. In addition, if the vital signs of a patient become unstable, it may be too late to treat with surgery or any other interventions. Therefore, if a radiologist identifies that a patient with a high likelihood of hemorrhage by CT before clinically significant bleeding occurs, it will be useful for the patient's management. For example, when the vital signs of a high-risk patient become very unstable, an intervention can be attempted before a CT scanning.

CT after Whipple surgery is usually performed to detect postoperative complications or for baseline imaging before adjuvant treatment, such as chemotherapy or radiotherapy. In our institution (PNUH), postoperative CT scans are usually taken within 7 days to detect complications, and these initial follow-up images are reviewed and the risk factors are investigated.

A pancreatic fistula after Whipple surgery occurs in roughly 6–14% of cases and indicates leakage of amylase-rich pancreatic juice from the pancreatic duct, usually at the site of a disrupted pancreaticojejunal anastomosis or at a site of damaged pancreatic parenchyma during the operation (

17). A pancreatic leak can trigger late PPH by enzymatically digesting the blood vessel wall via trypsin or elastase (

12). If the fluid around the PJ anastomosis on CT or amylase-rich fluid is present, pancreatic leakage is suspected (

1618). In this study, 66.2% of patients showed postoperative fluid along the PJ anastomosis on CT and 39.1% had amylase-rich fluid from an abdominal drainage tube. However, the fluid was not related to PPH and transient fluid collection in the surgical bed often occurs and vanishes spontaneously, even if it is rich in amylase (

19).

In 2007, Hashimoto et al. (

20) reported that CT findings of fluid collection around the PJ with an air bubble may strongly suggest the presence of a pancreatic fistula. In the present study, the patients who had 1-week postoperative CT manifestations of fluid collection containing air around the PJ were observed to likely develop late PPH. Thus, compared with the amylase-rich peritoneal fluid, CT depiction of fluid and air around the PJ is the most significant predictor of a pancreatic leak. It is also associated with vessel damage.

Together with the CT findings suggestive of a pancreatic fistula, fluid with high probability of infection including enhancing rim or gas detected on a 1-week postoperative CT scan was noted as an independent risk factor for late PPH in this study. These results are consistent with previous studies where pancreatic leaks and intra-abdominal sepsis are seen as independent risk factors for subsequent massive bleeding (

6821). A postpancreatectomy abscess can be caused by a pancreatic fistula, superinfection in collected acute postoperative fluid, leakage of HJ, or enteric anastomosis (

22). Thus, enteric, pancreatic, or biliary juice can erode vascular structures. Local inflammation or sepsis also induces a pseudoaneurysm (

8).

In addition, a PMN count > 250 cells/µL was not an independent risk factor for predicting late PPH like amylase-rich ascites. In this study, the sensitivity and specificity of the CT for postoperative abscess detection were 55.1% and 60%, respectively. Also, 1-week postoperative CT manifestations of fluid collection containing air around the PJ had a 42.4% sensitivity and a 73.9% specificity for detection of pancreatic fistula. Therefore, radiological findings suggestive of a pancreatic fistula or abscess could be important indicators predicting a patient's condition and late PPH, compared with laboratory results.

The researchers evaluated the presence of a hemoperitoneum when fluid density was > 20 HU and 27 patients had a hemoperitoneum on the first follow-up CT. Among them, significant bleeding occurred in only six and most of the hemoperitoneum was resorbed spontaneously on follow-up imaging. The initially detected hemoperitoneum was not seen as a predictor of late PPH in this study. Clinical sentinel bleeding, defined as the presence of blood in the abdominal drain tube or nasogastric tube 24 hours prior to late hemorrhage, is associated with late massive bleeding (

23). However, the color of peritoneal fluid from the abdominal drain tube was not associated with PPH in this study. Therefore, an early sentinel clot sign within 1 week was clinically and radiologically meaningless for predicting late hemorrhage.

In this study, the most common cause of late PPH was bleeding of the GDA stump (60%), followed by bleeding of the hepatic artery (20%) and ulcer (10%). The CHA and GDA were injured by skeletonization for lymphadenectomy, during pylorus-preserving pancreaticoduodenectomy and ligation of the arterial stump that was too tight (

24). These contributed to the relatively high incidence of GDA stump bleeding. Formation of a pseudoaneurysm is triggered by localized sepsis or pancreatic or biliary juice, as mentioned above.

In 2010, Sanada et al. (

5) reported that the GDA should be ligated at its root, such that the GDA stump cannot be visualized on arterial phase CT and a long GDA stump on CT suggests a predisposing condition for a pseudoaneurysm or its early stage. However, the length of the GDA stump is maintained at approximately 5 mm closed with a suture ligature, including our institution (PNUH) (

25).

In the present study, a visible GDA stump was detected on postoperative CT in 71 patients (47.0%) (mean size, 6.35 mm; range, 2.3–14 mm). Eighty patients (53.0%) did not show a protruding GDA stump on postoperative CT. Uni- and multivariate analyses revealed the size of the GDA stump measured on CT was larger in patients with versus without late PPH. The pressure on a larger-sized stump would increase and other triggering factors would have a greater chance of contacting the vulnerable stump. Although the GDA stump can be seen in various ways depending on the branching angle and the operative conditions, there is a higher risk of late PPH when the size of the GDA stump is > 4.45 mm on CT performed within 1 week of Whipple surgery.

Any low serum cholesterol level is a poor prognostic factor in older hospitalized adults and affects postoperative mortality (

26). This study also demonstrated that development of late PPH is inversely related to serum cholesterol levels and might be associated with poor health status. However, the serum amylase and the lipase levels, which reflect inflammation of the pancreas, were not associated with late PPH.

This study had several limitations. First, it was retrospective in nature. Thus, selection bias was possible, as only the patients who underwent triple- or dual-phase CT among those who underwent Whipple surgery in PNUH were included, potentially excluding some patients. However, the incidence of late PPH in this study was higher than the < 10% incidence reported in a previous study. This higher incidence may be due to a higher prevalence of malignancy, resulting in more complex operations, including vascular skeletonization for lymphadenectomy. Second, the occurrence of late PPH may have been influenced by various clinical factors that were not evaluated such as experience or skill of the hepatobiliary surgeon or the bleeding tendency of patients. Third, all CT examinations were performed in triple phases and were usually performed during the early postoperative period, so patients were exposed to unnecessarily high radiation doses. However, arterial bleeding can usually be detected in the arterial phase and several hemorrhages can be detected during the delayed phase.

In conclusion, late hemorrhage after Whipple surgery is an uncommon but serious complication. Early prediction of this complication is mandatory. Early postoperative CT before bleeding could play an important role in predicting late PPH. A GDA stump size > 4.45 mm, abscess, or pancreatic fistula on CT suggest an increased risk for late PPH and clinicians and radiologists should carefully follow such patients.

Go to :

PDF

PDF ePub

ePub Citation

Citation Print

Print

XML Download

XML Download