Abstract

We report an exceptional case of a de novo giant fusiform aneurysm of the basilar trunk, which developed shortly after the therapeutic occlusion of the right internal carotid artery for a fusiform carotid aneurysm. It would appear to be appropriate to call this entity a sequential giant fusiform aneurysm. The patient was successfully treated with endovascular occlusion of the giant basilar trunk aneurysm following bypass surgery.

Intracranial de novo aneurysms are rare and most of them are found years after the diagnosis of the initial aneurysms (1). The development of de novo giant fusiform aneurysms in the vertebrobasilar system after balloon occlusion for giant fusiform aneurysms of the internal carotid artery (ICA) is even rarer (2). The authors achieved successful occlusion of a de novo giant fusiform aneurysm of the basilar trunk in a young woman who had undergone therapeutic occlusion of the ICA seven months previously. In this report, we present our case and discuss the treatment strategy for this special entity, which we refer to as the sequential giant fusiform aneurysm.

A 30-year-old woman was admitted to our institution in June 2002 for the treatment of a giant fusiform aneurysm of the basilar trunk. A giant ICA aneurysm had been found during a previous evaluation of abducens nerve palsy on her right side in November 2001 (Fig. 1A). At that time, a tortuous basilar artery had been found, but without any aneurysmal dilatation (Fig. 1B). She had undergone endovascular trapping of the giant fusiform aneurysm, involving the petrous to cavernous parts of the right ICA, at another hospital (Fig. 1C). However, she developed severe headache seven months after the treatment. At the time of admission, she complained of progressive dyspnea, as well as dull headache in the occipital area. Neurologic examination revealed a 6th cranial nerve palsy on the right side and increased deep tendon reflexes in the four extremities. On MR imaging, a giant aneurysm of the basilar artery was found to be compressing the brain stem (Fig. 2A). Cerebral angiography showed a fusiform giant aneurysm, with an irregular contour, involving the basilar trunk (Fig. 2B). The left anterior inferior cerebellar artery originated just proximal to the basilar trunk aneurysm. In addition, another de novo small paraclinoid aneurysm was found on the left ICA.

To relieve the brain stem compression, we decided to obliterate the basilar trunk aneurysm in spite of the risk associated with this intervention. In advance of performing endovascular embolization of the aneurysm, a high-flow bypass from the external carotid artery to the middle cerebral artery was performed using a saphenous vein graft. This is because occlusion of the basilar trunk would have endangered the blood supply to the posterior circulation, leaving the left ICA as the only vessel responsible for the perfusion of the entire brain after the basilar trunk occlusion, since the patient had already undergone occlusion of the right ICA. The bypass supplied the right middle cerebral artery territory (Fig. 3A), and an adequate blood supply to the upper portion of the posterior circulation was maintained via the left posterior communicating artery (PCoA). During surgery, part of the occluded right ICA was sectioned and referred for pathologic examination, in an attempt to determine the etiology of the rapid sequential development of the giant fusiform aneurysm.

Follow-up angiography, performed three days after the bypass surgery, revealed a patent bypass graft. After a test balloon occlusion at the level of the proximal basilar artery, which ensured adequate perfusion to the upper parts of the brain stem and cerebellum through the left PCoA (Fig. 3B), coil embolization of the basilar trunk aneurysm was done. Fourteen detachable platinum coils with a total length of 155 cm were deployed in the aneurysm. Upon completion of the embolization procedure, the blood flow to the posterior circulation through the PCoA was maintained well, with near-complete occlusion of the aneurysm (Fig. 3C). Postprocedural heparinization was not done. The patient was managed in the neurosurgical intensive care unit and recovered without further neurologic deficit. However, six hours after the end of the embolization procedure, the patient developed dyspnea, dysarthria, and quadriparesis. Intubation and ventilator care was undertaken, and heparinization was started. Enlargement of the aneurysm due to thrombus was revealed by MR imaging, and angiography confirmed complete occlusion of the aneurysm. The patient became stable after two days and, one month after the intervention, independent daily activity became possible and she was discharged from hospital. Pathologic examination of the vessel specimen showed intraluminal projections of fibrous tissue with smooth muscle and capillary proliferation, but failed to reach a definite etiologic diagnosis.

Follow-up angiography performed three months and one year post-treatment, respectively, revealed complete and stable occlusion of the basilar trunk aneurysm and good perfusion to the entire brain. MR imaging showed marked shrinkage of the aneurysm of the basilar trunk, with no evidence of brain stem compression (Fig. 4). In contrast, the size of the carotid fusiform aneurysm showed no significant change. The patient is currently leading a normal life as a housewife.

Our case is noteworthy in that a giant fusiform aneurysm of the basilar trunk developed subsequent to therapeutic ICA occlusion for the giant fusiform carotid aneurysm. To the best of our knowledge, this is only the second case report of a sequential giant fusiform aneurysm of the vertebrobasilar artery which developed after ICA occlusion for a giant fusiform carotid aneurysm.

Johnston et al. (2) reported the development of a de novo fusiform aneurysm of the vertebrobasilar artery after carotid occlusion for fusiform carotid aneurysm in a series of 3 cases. In their report, the first case was a 10-year-old boy presenting with a fusiform giant ICA aneurysm. Two years after successful occlusion of the ICA, he developed another giant fusiform aneurysm involving the vertebrobasilar junction. The second case was a 6-year-old boy presenting with a fusiform giant ICA aneurysm. Five years after successful occlusion of the ICA, a giant fusiform distal vertebral artery aneurysm was found. The last case was a 10-year-old girl presenting with a fusiform giant ICA aneurysm. Eleven years after occlusion of the ICA, a giant fusiform basilar trunk aneurysm was found to have developed.

We suggest the term 'sequential giant fusiform aneurysm' be used to represent a distinctive group of aneurysms presenting in childhood and young adulthood. The situation and sequence of events associated with this group of aneurysms are quite stereotypic: 1) the patient presents with a giant fusiform carotid aneurysm, 2) receives therapeutic carotid occlusion, and 3) returns at a later date with another de novo giant fusiform vertebrobasilar aneurysm.

Some minor differences are noted between our case and the previously reported cases. In the cases reported by Johnston et al. (2), the initial angiography showed normal-looking vertebrobasilar arteries, while our case already showed severe tortuosity of the basilar artery on the first angiography. Another difference is the interval between the initial aneurysm and the development of the de novo fusiform aneurysm: two to 11 years versus seven months in our case. At the time of the first evaluation, the age of the patients ranged from six to 10 years in the previous report, while our patient was older (30 years old) at the time of the initial diagnosis. We suppose that our patient might have had a more advanced stage of the disease and that this was responsible for the differences between our case and the cases reported previously.

In summary, this particular entity, namely sequential giant fusiform aneurysms involving the carotid and vertebrobasilar arteries in adolescents or young adults, is noteworthy. Its etiology still remains to be clarified and special concern is therefore required in treating children or young adults with fusiform carotid aneurysms.

When a fusiform aneurysm is located in the basilar trunk, its treatment is quite challenging. In a large surgical series of 32 cases of giant basilar trunk aneurysms of the fusiform type, the main treatment strategy was proximal basilar artery occlusion or trapping, resulting in seven cases of mortality and five cases of morbidity (3). In another series, there were three mortalities among eight cases of basilar artery fusiform aneurysm (4).

There have been several reports of fusiform basilar artery aneurysms treated by endovascular means, using coils and/or stents (5-7). In eccentrically bulging, broadneck aneurysms, the placement of a flexible stent, followed by coil embolization, may be a legitimate treatment option (5, 6). In giant fusiform aneurysms, stent placement followed by stent graft placement may also be an alternative treatment option (7). Stent placement has the advantage of allowing the maintenance of the parent arterial lumen, but clinical use of this technique is limited by the difficulty associated with the endovascular navigation of stents into the cerebral vasculature (7). In cases such as our own with extremely tortuous arteries, this treatment modality using stents appears infeasible.

Parent vessel occlusion by surgical or endovascular means may be another treatment option (8, 9). In a series of vertebrobasilar aneurysms treated by parent vessel occlusion, delayed neurological complication was reported in 45 % of the cases and the majority of these complications were found to be fatal (8). Furthermore, in aneurysms involving the basilar artery, complete thrombosis cannot be achieved by the occlusion of the parent vessel (9). In determining the safety of basilar artery occlusion, it is known that the most important factor is the presence and size of the PCoAs, and those patients in whom both PCoAs were more than 1 mm in diameter showed better outcomes (8). Our patient had only one, albeit large, PCoA originating from the left ICA, which was responsible for the perfusion of both hemispheres. In addition, a prominent anterior inferior cerebellar artery arising just proximal to the aneurysm precluded the option of parent vessel occlusion.

Therefore, the strategy that we adopted was complete occlusion of the aneurysm, followed by bypass to support the cerebral perfusion, even though it was likely that the brain stem perforators incorporated into the aneurysm would be occluded by this procedure. We checked the brain stem perfusion by performing a test balloon occlusion at the level of the proximal basilar artery, which ensured adequate perfusion to upper parts of the brain stem and cerebellum through the left PCoA, in advance of the embolization of the aneurysm.

Bypass surgery seems to be an essential element in the treatment of this special group of patients in which one carotid artery is already occluded, because of the increased hemodynamic burden placed on the other carotid artery when the vertebrobasilar artery is sacrificed. It is important to ensure perfusion of the entire cerebrum, as well as to eliminate the aneurysm.

Our case showed deterioration six hours after the endovascular embolization, caused by the expansion of the aneurysm due to acute thrombosis. Unfortunate worsening of the mass effect may occur shortly after endovascular treatment, resulting in the compression of the surrounding brain parenchyma or vascular structures, leading to cerebral infarction (10). Therefore, controlling thrombosis by anticoagulation seems to be required when treating giant aneurysms with coil embolization or parent vessel occlusion, and postembolization intensive care has a role to play in managing such cases.

Concerns may be raised as to the efficacy of coil embolization in alleviating neurologic deficits caused by mass effects (11). In this respect, our case provides an example showing the effectiveness of endovascular embolization. Furthermore, we witnessed the near complete shrinkage of the giant fusiform aneurysms during the one year period post-treatment.

Figures and Tables

Fig. 1

A. The AP view of a right internal carotid artery angiogram showing a giant fusiform aneurysm involving the petrous to cavernous parts in a 30-year-old woman.

B. The vertebral angiogram shows the extremely tortuous course of the vertebrobasilar arteries without aneurysmal dilatation.

C. The aneurysm is no longer visible on the lateral view of the right internal carotid artery angiogram after endovascular trapping.

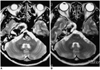

Fig. 2

A. MR imaging, taken seven months after therapeutic occlusion of the right internal carotid artery, shows a large signal void in the basilar artery area, exerting a mass effect on the brain stem.

B. Angiogram reveals a giant fusiform aneurysm of the basilar trunk, just distal to the origin of the left anterior inferior cerebellar artery.

Fig. 3

A. Angiogram, taken after the external carotid artery to middle cerebral artery bypass using the saphenous vein graft, shows a patent bypass and an adequate perfusion to the middle cerebral artery territory through the bypass.

B. Test balloon occlusion at the level of the proximal basilar artery ensures adequate perfusion to the upper parts of the brain stem and cerebellum through the left posterior communicating artery.

C. Angiogram, taken at the completion of embolization, shows near complete obliteration of the aneurysm.

References

1. Rinne JK, Hernesniemi JA. De novo aneurysms: special multiple intracranial aneurysms. Neurosurgery. 1993. 33:981–985.

2. Johnston SC, Halbach VV, Smith WS, Gress DR. Rapid development of giant fusiform cerebral aneurysms in angiographically normal vessels. Neurology. 1998. 50:1163–1166.

3. Drake CG, Peerless SJ. Giant fusiform intracranial aneurysms: review of 120 patients treated surgically from 1965 to 1992. J Neurosurg. 1997. 87:141–162.

4. Anson JA, Lawton MT, Spetzler RF. Characteristics and surgical treatment of dolichoectatic and fusiform aneurysms. J Neurosurg. 1996. 84:185–193.

5. Higashida RT, Smith W, Gress D, Urwin R, Dowd CF, Balousek PA, et al. Intravascular stent and endovascular coil placement for a ruptured fusiform aneurysm of the basilar artery. Case report and review of the literature. J Neurosurg. 1997. 87:944–949.

6. Phatouros CC, Sasaki TY, Higashida RT, Malek AM, Meyers PM, Dowd CF, et al. Stent-supported coil embolization: the treatment of fusiform and wide-neck aneurysms and pseudoaneurysms. Neurosurgery. 2000. 47:107–113.

7. Islak C, Kocer N, Albayram S, Kizilkilic O, Uzma O, Cokyuksel O. Bare stent-graft technique: a new method of endoluminal vascular reconstruction for the treatment of giant and fusiform aneurysms. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol. 2002. 23:1589–1595.

8. Steinberg GK, Drake CG, Peerless SJ. Deliberate basilar or vertebral artery occlusion in the treatment of intracranial aneurysms. Immediate results and long-term outcome in 201 patients. J Neurosurg. 1993. 79:161–173.

9. Leibowitz R, Do HM, Marcellus ML, Chang SD, Steinberg GK, Marks MP. Parent vessel occlusion for vertebrobasilar fusiform and dissecting aneurysms. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol. 2003. 24:902–907.

10. Blanc R, Weill A, Piotin M, Ross IB, Moret J. Delayed stroke secondary to increasing mass effect after endovascular treatment of a giant aneurysm by parent vessel occlusion. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol. 2001. 22:1841–1843.

11. Halbach VV, Higashida RT, Dowd CF, Barnwell SL, Fraser KW, Smith TP, et al. The efficacy of endosaccular aneurysm occlusion in alleviating neurological deficits produced by mass effect. J Neurosurg. 1994. 80:659–666.

PDF

PDF ePub

ePub Citation

Citation Print

Print

XML Download

XML Download