To the Editor:

The article on hazardous drinking and depression by Park et al. (1) was quite interesting and informative. The finding of severe symptoms and greater burden of illness in persons with depression and comorbid problematic drinking reinforces current understanding of this common form of heterotypic comorbidity. The co-occurrence of mental health problems with hazardous drinking in this study raises important questions about the etiology of mental and substance use disorders (2). The etiology of these comorbid disorders is most likely multi-factorial involving interactions between biological (genetic), psychological and social factors (for example, childhood abuse, trauma, poverty, lack of social capital). Genetic epidemiological studies suggest that alcohol dependence and depression are not transmitted independently, but the genetic and specific environmental sources of liability to major depression overlap with those underlying alcohol dependence (3). Several explanations have been suggested for the occurrence of mental health problems among alcohol users. An important one is the "shared vulnerability model" that posits that there are underlying genetic or other general susceptibility traits that contribute to both alcohol use and observed psychological or behavioural disturbances (4). Another possibility is that some psychiatric disturbances might prompt or increase alcohol consumption. For example, individuals with depressed moods might use alcoholic beverages to self-medicate in 2008 (5). In addition, the social acceptability and availability of alcohol may contribute to the consumption of hazardous quantities. This is more so in many societies where binge drinking is a recognized part of social events and religious ceremonies. In the context of serious mental illnesses like depression, the possibility of hazardous drinking may be increased further by impaired judgment.

Park et al. (1) also observed that 'cross-cultural differences can contribute to the under-diagnosis of depressive disorder and close relationship between hazardous drinking and suicidal ideation in Korea'. This is more so in societies where mental illness is heavily stigmatized and suicidality is not often expressed publicly. In view of this, the authors could have provided more information on the drinking patterns in Korea since drinking patterns have been consistently reported to vary by culture and geographical locations (6). For instance, alcohol is rarely consumed on a daily basis in Mexico, rather its use is usually linked with special occasions including weekends, festivities and paydays during which large amounts are consumed. This drinking pattern contrasts with findings in some parts of Europe for example, France and Portugal where drinking is well integrated into everyday activities (7).

Clearly, the relationship between alcohol use and depression has been confounded by genetic, personality and environmental factors that will continue to require additional research and attention. Nevertheless, the article provides some evidence for integrating screening for alcohol related problems during mental health assessments. There may also be a need for community based interventions focused on changing societal attitude to mental illness in order to improve social support available for persons with depression and/or problematic drinking (8). Better understanding and management of comorbid mental conditions may potentially reduce morbidity and mortality in persons with mental disorders.

References

1. Park SC, Lee S, Oh H, Jun TY, Lee M, Kim JM, Kim JB, Yim HW, Park YC. Hazardous Drinking-Related Characteristics of Depressive Disorders in Korea: The CRESCEND Study. J Korean Med Sci. 2015; 30:74–81.

2. Degenhardt L, Hall W, Lynskey M. Alcohol, cannabis and tobacco use among Australians: a comparison of their associations with other drug use and use disorders, affective and anxiety disorders, and psychosis. Addiction. 2001; 96:1603–1614.

3. Patel V. Alcohol Use And Mental Health In Developing Countries. Ann Epidemiol. 2007; 17:S87–S92.

4. Baigent M. Understanding Alcohol Misuse and Comorbid Psychiatric Disorders. Current Opinion in Psychiatry. 2005; 18:223–228.

5. Crum R, Storr C, Ialongo I, Anthony J. Is depressed mood in childhood associated with an increased risk for initiation of alcohol use during early adolescence? Addictive Behaviors. 2008; 33:24–40.

6. Wilsnack R, Wilsnack S, Kristjanson A, Vogeltanz-Holm N, Gmel G. Gender and alcohol consumption: patterns from the multinational GENACIS project. Addiction. 2009; 104:1487–1500.

7. Bloomfield K, Allamani A, Beck F, Bergmark KH, Csemy L, Eisenbach-Stangi I, Elekes Z, Gmel G, Kerr-Correa , Knibb R, et al. Gender, Culture, and Alcohol Problems A Multi-National Study. Project Final Report. 2005. 29/10/2011.

8. Abayomi O, Adelufosi AO, Olajide A. Changing attitude to mental illness among community mental health volunteers in south-western Nigeria. Inter J Social Psychiatry. 2013; 59:609–612.

We greatly appreciate your comments on our article in J Korean Med Sci (1). Our article has briefly discussed the etiology of co-occurrence of alcohol abuse and depression, because of the emphasis on clinical characterization of depressed patients with hazardous drinking behavior. Your comments give us a chance to enlighten the value of our findings.

Based on the relatively high co-occurrence rate (51.0%) of hazardous drinking among patients with depressive disorders in our findings, we speculate that socio-cultural factors can significantly influence this comorbidity in Korea. Among Korean men, heavy alcohol consumption has been permitted and encouraged in specific social circumstances (2, 3); this trend has contributed to the greater prevalence of alcohol dependence among men in Korea than in the United States (4). Although women were not allowed to drink according to traditional Korean culture (mainly, Confucianism), modern women begin drinking at a young age and acculturation has increased the use of alcohol among women (5). Thus, the relatively high co-occurrence of hazardous drinking and depressive disorders in our article could be attributed to the gender bias in alcohol consumption in Korea.

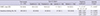

Using a simple regression model, a significant linear pattern was fitted to the relationship curve between severity of depression and alcohol consumption among men (Fig. 1A; R2=0.060, β=0.396, P=0.003). Conversely, among women (Fig. 1B), no significant relationship was evident (R2=0.002, β=0.054, P= 0.510). This gender difference in the pattern is consistent with previous findings (6). However, non-linear (U- and J-) shape patterns have been reported for the relationship among specific Korean populations, including men and the elderly (both gender), respectively (6, 7). Lack of an inverse association between moderate depression and alcohol consumption can be attributed to many factors including differences among the study subjects; of these factors, religion and its correlates can be considered as one of the factors modulating the relationship. Park et al. (8) reported the interesting finding that spiritual value is directly proportional to the presence of depressive disorders and inversely proportional to presence of alcohol use disorders. Using the binary logistic regression model in additional analyses of our findings (Table 1), the type of religion showed no significant association with the presence of hazardous drinking. Conversely, using the analysis of covariance (ANCOVA) and Turkey's post-hoc test, Catholics were shown to have significantly less severe depression than atheists and persons of other religions (F=2.747, P=0.043).

In conclusion, with shared vulnerability and self-medication, socio-cultural factors could influence the co-occurrence of hazardous drinking and depressive disorders in our findings. Additional analyses could further support the significant linear relationship between severity of depression and alcohol consumption among men. These findings may be attributed to religious and other cultural factors. However, the factors influencing the relationship between hazardous drinking and depressive disorders should be investigated in future studies.

Figures and Tables

Fig. 1

Relationship between scores on the HAMD (horizontal axis) and AUDIT (vertical axis). AUDIT, Alcohol Use Disorder Identification Test; HAMD, Hamilton Depression Rating Scale. (A) Men (n = 151), (B) Women (n = 251).

Table 1

Potential impact of type of religion on depressive severity and presence of hazardous drinking

References

1. Park SC, Lee SK, Oh HS, Jun TY, Lee MS, Kim JM, Kim JB, Yim HW, Park YC. Hazardous drinking-related characteristics of depressive disorders in Korea: the CRESCEND study. J Korean Med Sci. 2015; 30:74–81.

2. Helzer JE, Canino GJ, Yeh EK, Bland RC, Lee CK, Hwu HG, Newman S. Alcoholism: North America and Asia. A comparison of population surveys with the Diagnostic Interview Schedule. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1990; 47:313–319.

3. Yamamoto J, Rhee S, Chang DS. Psychiatric disorders among elderly Koreans in the United States. Community Ment Health J. 1994; 30:17–27.

4. Lee HK, Chou SP, Cho MJ, Park JI, Dawson DA, Grant BF. The prevalence and correlates of alcohol use disorders in the United States and Korea: a cross-national comparative study. Alcohol. 2010; 44:297–306.

5. Kim W, Kim S. Women's alcohol use and alcoholism in Korea. Subst Use Misuse. 2008; 43:1078–1087.

6. Noh JW, Juon HS, Lee S, Kwon YD. Atypical epidemiologic finding in association between depression and alcohol use or smoking in Korean male: Korean longitudinal study of aging. Psychiatry Investig. 2014; 11:272–280.

7. Kim SA, Kim E, Morris RG, Park WS. Exploring the non-linear relationship between alcohol consumption and depression in an elderly population in Gangneung: the Gangneung Health Study. Yonsei Med J. 2015; 56:418–425.

8. Park JI, Hong JP, Park S, Cho MJ. The relationship between religion and mental disorders in a Korean population. Psychiatry Investig. 2012; 9:29–35.

PDF

PDF ePub

ePub Citation

Citation Print

Print

XML Download

XML Download