Abstract

Paragonimiasis is caused by ingesting crustaceans, which are the intermediate hosts of Paragonimus. The involvement of the brain was a common presentation in Korea decades ago, but it becomes much less frequent in domestic medical practices. We observed a rare case of cerebral paragonimiasis manifesting with intracerebral hemorrhage. A 10-yr-old girl presented with sudden-onset dysarthria, right facial palsy and clumsiness of the right hand. Brain imaging showed acute intracerebral hemorrhage in the left frontal area. An occult vascular malformation or small arteriovenous malformation compressed by the hematoma was initially suspected. The lesion progressed for over 2 months until a delayed surgery was undertaken. Pathologic examination was consistent with cerebral paragonimiasis. After chemotherapy with praziquantel, the patient was monitored without neurological deficits or seizure attacks for 6 months. This case alerts practicing clinicians to the domestic transmission of a forgotten parasitic disease due to environmental changes.

Paragonimiasis is a parasitic disease caused by ingesting crustaceans, such as crabs or crayfish, that are infested with the metacercariae of Paragonimus (1). Paragonimiasis is prevalent in many Asian and African countries (2). Korea was once endemic for the disease because Korean people traditionally ate soybean-sauced freshwater crabs, of which Paragonimus infestation rates were high (3). The disease mainly involves the lung, but other organs can also be affected. The brain is the most common site of extrapulmonary paragonimiasis (1). In the 1950's and 1960's, cerebral paragonimiasis was quite prevalent in Korea, and treatment of the disease was one of the chief duties of Korean neurosurgeons (4). Since the 1970's, economic development and improvement of public hygiene have decreased the prevalence of the parasitic disease in Korea. Cerebral paragonimiasis has been an unfamiliar disease to the general public and to medical community for a long time. However, sporadic cases of paragonimiasis are occasionally observed in Korea because of the spread of infested, intermediate hosts into domestic streams and because of the increasing importation of infested crabs from endemic countries (5).

Here, we report the case study of a young patient with cerebral paragonimiasis who presented with intracerebral hemorrhage, an atypical manifestation of the disease. Both the rarity of the disease in current domestic medical milieu and the atypical presentation pattern made the diagnosis a challenging task. This case warns clinicians that cerebral paragonimiasis is not an outdated disease and that this forgotten parasitic disease could return because of environmental and social changes in Korea.

On June 2011, a 10-yr-old, previously healthy girl visited the emergency room (ER) because of sudden-onset dysarthria, right facial palsy and clumsiness of the right hand. She lived in Gwacheon, Korea with her parents. The patient was alert and oriented. The motor power of her right hand and arm was classified as grade V, but fine movements of her right hand and fingers were impaired.

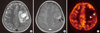

Brain computed tomography (CT) (Fig. 1A) and magnetic resonance image (MRI) (Fig. 1B) showed acute intracerebral hemorrhage in the left frontal convexity surrounded by edema involving the precentral motor cortex. The scans showed faint contrast-enhancement along the periphery (Fig. 1C, D). The initial diagnosis was a ruptured vascular malformation. Cerebral angiography was performed, but it did not reveal any vascular abnormalities. An occult vascular malformation or a small arteriovenous malformation (AVM) compressed by the hematoma were still suspected. In her initial complete blood count (CBC) test, white blood cell count was within the normal range (8.91 × 103/µL) but eosinophils comprised 20.0% of total white blood cells (WBC). However, the CBC result was then overlooked.

A follow-up appointment with careful clinical and imaging procedures was planned. The patient's neurological deficits had disappeared and she was discharged with antiepileptic drugs. One month after the discharge, no significant changes were detected by the follow-up MRI. Surgical exploration of the lesion site was planned, but the parents of the patient refused to consent to the operation. Two months after the initial onset of symptoms, the patient visited the ER again because she developed a partial motor seizure involving right facial twitching and tonic movement of her right hand. She did not take antiepileptic drugs for several days. On a follow-up MRI, the size of pre-existing hematoma and the surrounding edema increased (Fig. 2A). A bubble-like lesion with rim-enhancement appeared at the posterior aspect of the hematoma (Fig. 2B). Considering the patient's clinical course and the progression of the brain lesion, it was strongly suspected the cause of the lesion was due to bleeding from an intra-axial tumor, presumptively of a high grade. However, no hypermetabolism suggestive of malignancy was detected by 18F-fluorodeoxyglucose positron emission tomography (FDG-PET) (Fig. 2C).

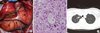

In August 2011, we performed an exploratory craniotomy for biopsy and hematoma removal. After craniotomy, a hemorrhagic cyst was found underneath a thinned brain cortex. The cyst was located in the middle frontal gyrus just anterior to the precentral gyrus (Fig. 3A). After making a small cortisectomy, the large hemorrhagic cyst was removed. The cyst had a tough wall and contained a partially-liquefied hematoma. In the posterior and medial side of the cyst, a reddish friable mass with a clear margin was found. The mass was thoroughly removed with forceps and suction. The frozen biopsy of the mass revealed a considerable amount of plasma cells without tumor cells. The pial layer of the precentral gyrus was secured throughout the operation. After the operation, the patient recovered without neurological deficits. Pathologic examination revealed overt parasite infestation. There were ovoid, asymmetric eggs having thick shells with chronic granulomatous inflammation and heavy eosinophilic infiltration (Fig. 3B) (6).

The diagnosis of cerebral paragonimiasis was virtually unexpected. Upon asking the patient about any prior intake of raw crabs, the patient reported having ingested soybean-sauced freshwater crabs in a restaurant located in Bundang-gu, Seongnam, Korea twice several months ago. Further evaluations such as chest CT scans and serum enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) were performed after pathological diagnosis of paragonimasis to reinforce the diagnosis. The patient had no pulmonary symptoms, but chest CT scans revealed multiple cavitary lesions with irregular walls at the apex of the right upper lobe of the lung (Fig. 3C). Serum antibody levels corresponding to multiple parasites were measured using an enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA). The ELISA activity for paragonimiasis was 0.359, higher than the reference limit (0.280). In addition, reviewing the CBC test at the first admission, we noticed the abnormally high proportion of eosinophils in peripheral blood.

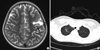

A dosage of 75 mg/kg of praziquantel was administered to the patient for 2 days. The patient was followed-up for 9 months from the operation and did not presented with neurological deficits or seizure attacks. Follow-up brain MRI showed no recurrent lesion (Fig. 4A) and chest CT scans were clear (Fig. 4B).

After the diagnosis and treatment, serum ELISA test for paragonimiasis was recommended to her parents and her mother showed a positive ELISA result. A CBC test of the mother revealed peripheral eosinophilia (7.9% of the total WBC count) and chest CT scans of the mother also showed multiple cavitary lesions in the left upper lobe (Fig. 5A). Immediate antihelminthic treatment was recommended, but the mother refused treatment and was lost to follow-up. Six months later, the mother visited emergency room for fever, cough, and sputum. On chest x-ray, hydropneumothorax in the left side was observed (Fig. 5B). The cavitary lesions had much progressed on chest CT scans. She received a chest tube insertion procedure and took praziquantel for 4 days. Because of recurrent pneumothorax during hospitalization, she received a lobectomy of the involved lung. Pathological examinations showed eggs of Paragonimus westermani.

In the 1950's and 1960's, parasite infestation was one of the major public health problems of Korea. Pulmonary paragonimiasis was rampant because the juice of crushed crayfish was used as a medication for measles (5). Cerebral paragonimiasis occurs in a quarter of the patients who develop pulmonary paragonimiasis. Therefore, cerebral paragonimiasis was the most common "brain tumor" occurring in Korean people during the 1950's and 1960's (3). Surgical resection was the only treatment for cerebral paragonimiasis until bithionol was introduced as a chemotherapeutic agent for paragonimiasis in 1962. In fact, the first hemispherectomy in Korean neurosurgery was performed in 1958 on a 21-yr-old male patient with excessive cerebral paragonimiasis (4, 7).

Since the 1970's, the prevalence of paragonimiasis has decreased markedly because of nationwide stool exams, mass chemotherapy treatment with bithionol or praziquantel and public education in personal prophylaxis. The incidence of larvae in the intermediate host has also diminished because of the broad spray of pesticides and because the construction of dams has changed the river ecosystem (8). A field study published in 2009 reported that no metacercaria of Paragonimus westermani was found in 363 freshwater crabs examined from 6 different localities in the country (5). The result in this study implies that the transmission of Paragonimus by freshwater crabs is presently very rare in Korea.

Several papers reporting on cerebral paragonimiasis were published in the fields of neurosurgery and neuroradiology in the 1980's and 1990's. However, the prevalence of cerebral paragonimiasis has decreased in recent years. Only a few neurosurgical cases have been reported after 2000 in Korea (9-11). Therefore, cerebral paragonimiasis is an unfamiliar disease to the contemporary neurosurgeons and neuroradiologists in Korean.

The rarity of this disease in contemporary neurosurgical practices and atypical presentation with intracranial hemorrhage made the diagnosis delayed. There may have been many clues for the diagnosis of paragonimiasis, if appropriately asked or sought before the operation: an intake history of raw freshwater crabs, typical symptomatology of partial seizures, peripheral eosinophilia, positive ELISA results, and suspicious brain and chest imaging findings. Nonetheless, because of the long obsoleteness of this disease entity in the neurosurgical field in Korea, the practicing neurosurgeons and neuroradiologists were short of clinical suspicion for the disease. Although negative angiography and FDG-PET findings evoked some skepticism about the diagnoses of AVM or a high-grade brain tumor, cerebral paragonimiasis was still out of the way in the preoperative diagnosis.

On pathological examinations, we found only eggs of Paragonimus westermani but no body of worms. The liquefied hematoma was largely aspirated with suction devices used for neurosurgical operations. Therefore, it was possible that the worms were lost by the suction and only inflammatory tissues and some eggs were left for histological examinations.

Food-borne parasite infestation warrants screening examination for other family members. In this case, the mother of the patient showed evidence of pulmonary paragonimiasis: positive ELISA test, peripheral eosinophia, and cavitary lesions on chest imagings. The clinical course of the mother was complicated as she refused antihelminthic treatment in asymptomatic period and later developed serious hydropneumothorax that required surgical resection of the involved lung lobe.

Wild freshwater crabs are produced more than before because of improved conservation of the river ecosystems of Korea (5). Also some wildlife reservoirs are keeping this worm in the nature. In addition, cultured freshwater crabs from China where paragonimiasis is still endemic are distributed in markets (12). The restaurants serving soybean-sauced freshwater crabs are gaining popularity recently (13). It is concerned that environmental alterations and life-style changes can induce resurgence of this formerly prevalent infectious disease.

Figures and Tables

Fig. 1

Brain images of the patient at initial presentation (June 2011). (A) A pre-contrast CT scan reveals an acute intracerebral hemorrhage with surrounding edema in the left frontal lobe. (B) Left frontal lesion shows hypointensity with surrounding hyperintensity on a T2-weighted MR image. (C) On a T1-weighted MR image, the lesion shows hypointensity with curvilinear hyperintensity. These findings suggest an acute to early subacute hematoma. (D) A contrast-enhanced T1-weighted MR image demonstrates a faint, encircling ring enhancement (arrows).

Fig. 2

Follow-up imaging studies obtained two months after the initial onset of symptoms (August 2011). (A) A T2-weighted MR image reveals a chronic hematoma with extensive surrounding edema in the left frontal area. (B) There are newly emerging conglomerated, bubbly enhancing lesions at the posterior aspect of the hematoma on a contrast-enhanced T1-weighted MR image (arrows). (C) A FDG-PET image reveals a metabolic defect in the left frontal lobe (arrowheads).

Fig. 3

Surgical and pathologic findings (August 2011). (A) An operative photograph shows a hemorrhagic cyst located in the middle frontal gyrus just anterior to the precentral gyrus (arrows). (B) Hematoxylin and eosin staining reveals an egg of Paragonimus (arrow) along with granulomatous inflammation (× 200). Note the thick asymmetric shell with a flattened side (arrow). (C) A chest CT scan (September 2011) reveals conglomerated, thin-walled cystic lesions with a nodule at the apex of the right upper lobe (arrow).

References

1. Choi DW. Paragonimus and paragonimiasis in Korea. Korean J Parasitol. 1990. 28:Suppl. 79–102.

2. Cha SH, Chang KH, Cho SY, Han MH, Kong Y, Suh DC, Choi CG, Kang HK, Kim MS. Cerebral paragonimiasis in early active stage: CT and MR features. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 1994. 162:141–145.

3. Oh SJ. Cerebral paragonimiasis. J Neurol Sci. 1969. 8:27–48.

4. Park J, Miyagawa T, Hong J, Kim O. Cerebral paragonimiasis and Bo Sung Sim's hemispherectomy in Korea in 1950s-1960s. Korean J Med Hist. 2011. 20:119–161.

5. Kim EM, Kim JL, Choi SI, Lee SH, Hong ST. Infection status of freshwater crabs and crayfish with metacercariae of Paragonimus westermani in Korea. Korean J Parasitol. 2009. 47:425–426.

6. Kang SY, Kim TK, Kim TY, Ha YI, Choi SW, Hong SJ. A case of chronic cerebral paragonimiasis westermani. Korean J Parasitol. 2000. 38:167–171.

7. Sim BS, Chu CW, Suh YW, Youn KC. Cerebral hemispherectomy for control of intractable convulsions caused by diffuse cerebral paragonimiasis. J Korean Surg Soc. 1962. 4:379–388.

8. Lee MK, Hong SJ, Kim HR. Seroprevalence of tissue invading parasitic infections diagnosed by ELISA in Korea. J Korean Med Sci. 2010. 25:1272–1276.

9. Lee WJ, Koh EJ, Choi HY. Epilepsy surgery of the cerebral paragonimiasis. J Korean Neurosurg Soc. 2006. 39:114–119.

10. Lim SH, Cho HC, Lee KY, Lee YJ, Koh SH. Cerebral paragonimiasis presenting as recurrent hemorrhagic stroke without pulmonary symptoms. J Korean Neurol Assoc. 2011. 29:371–373.

11. Choo JD, Suh BS, Lee HS, Lee JS, Song CJ, Shin DW, Lee YH. Chronic cerebral paragonimiasis combined with aneurysmal subarachnoid hemorrhage. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2003. 69:466–469.

12. The Hankyoreh. No Paragonimus in well fertilized crabs. 2004. 07. 01. accessed on 8 April 2012. Available at http://legacy.www.hani.co.kr/section-005100033/2004/07/005100033200407011953640.html.

13. The Kukminilbo. Be careful for paragonimiasis by eating soybean sauceed crabs: Recent resurge of paragonimiasis patients. 2006. 06. 28. accessed on 19 June 2012. Available at http://news.naver.com/main/read.nhn?mode=LSD&mid=sec&sid1=103&oid=005&aid=0000249546.

PDF

PDF ePub

ePub Citation

Citation Print

Print

XML Download

XML Download