Abstract

Cerebral air embolism is a rare but fatal complication of central venous catheterization. Here, we report a case of paradoxical cerebral air embolism associated with central venous catheterization. An 85-yr-old man underwent right internal jugular vein catheterization, and became obtunded. Brain MR imaging and CT revealed acute infarction with multiple air bubbles on the side of catheter insertion. The possibility of cerebral air embolism should be considered in patients developing neurological impairment after central venous catheterization, and efforts should be made to limit cerebral damage.

Central venous catheter insertion into the jugular or subclavian vein is a commonly performed procedure. Complications, such as local hematoma, pneumothorax, and/or hemothorax, are usually associated with the insertion procedure itself (1). One of the most serious complications is potentially fatal cerebral air embolism (2). Diffusion-weighted imaging (DWI) has been widely used for prompt workup in patient with acute neurological deterioration. Here, we report a very rare case of lethal paradoxical cerebral air embolism that occurred following insertion of a catheter in the jugular vein, and showed extensive hemispheric acute cerebral infarction with multiple air bubbles on DWI and CT.

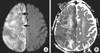

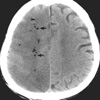

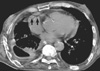

An 85-yr-old man was admitted to hospital with community-acquired pneumonia on December 21, 2007. He had been suffering from dyspnea due to right fibrothorax associated with pulmonary tuberculosis. His baseline pulmonary function test revealed FEV1/FVC of 89%, FEV1 of 25%, and FVC of 18% predicted values. He was treated with mechanical ventilation for three months and received long-term care at the intensive care unit (ICU) for four months. After removal of the ventilator, the patient was transferred to a general ward for further planning of rehabilitation treatment. However, the patient suffered new-onset atrial fibrillation, after which his oral intake decreased. His general condition deteriorated and he became dehydrated. Therefore, a central venous catheter was placed in the right internal jugular vein for more intensive treatment, including bedside fluid and nutritional therapy, without imaging guidance. Three days after the procedure, he slept all day. When awakened, he answered only briefly with slurred speech. He tended to gaze toward the right. No movement of the extremities on the left side was seen. At this point, he had no circulatory impairment. DWI was performed to evaluate neurological problems and revealed extensive hyperintensity with decreased apparent diffusion coefficient (ADC) value in the right cerebral hemisphere suggesting acute cerebral infarction. There were mottled areas of low signal intensity within the acute infarct area, which were considered to be air bubbles (Fig. 1). With a diagnosis of suspected paradoxical cerebral air embolism, brain and chest CT were performed simultaneously. An extensive area of low attenuation suggesting acute infarction in the right cerebral hemisphere as well as air bubbles mainly in the border zone areas of the right hemisphere were observed on brain CT (Fig. 2), and free air was detected in the right atrium on chest CT (Fig. 3). Transesophageal echocardiography (TEE) revealed microbubbles in the aorta without visible intracardiac shunt after injection of agitated saline (Fig. 4).

The patient was suggested to have paradoxical cerebral air embolism associated with central catheterization. We removed the catheter and considered hyperbaric oxygen therapy. However, the patient was too unstable for transfer to a facility with a hyperbaric chamber (3); therefore, hyperbaric oxygen therapy could not be applied. The patient's condition deteriorated and he died on day six after central venous catheterization.

Air embolism is a potentially catastrophic event and can involve the venous or arterial vasculature (2). Venous embolism occurs when air enters the systemic venous system. The air is transported to the lung through the pulmonary arteries, causing interference with gas exchange, cardiac arrhythmia, pulmonary hypertension, and right ventricular strain. Arterial embolism is caused by the entry of gas into the pulmonary vein or directly into the arteries of the systemic circulation. Although obstruction is possible in all arteries, obstruction of either the coronary or brain artery is serious and may be fatal. A paradoxical air embolism occurs when air that has entered the venous circulation enters the systemic arterial circulation. Therefore, patients present with symptoms of end-artery obstruction.

Cerebral air embolism occurs under various conditions, such as central catheter insertion and removal (4-9), accidental disconnection of a central catheter (10-12), cardiac ablation procedure (13), pulmonary barotrauma, and thoracic or cardiac surgery (2). The reported frequency of air embolism associated with use of a central catheter ranges from 0.1% (1) to 2% (8), with a total mortality rate of 23% (12). The risk of catheter-related air embolism is increased by a number of factors that reduce central venous pressure (2, 8), such as deep inspiration during insertion or removal, hypovolemia, and upright position of the patient.

In the present case, neurological deficit was detected three days after central catheterization. The exact time of embolism is uncertain, but we presume that embolization and infarction occurred at the time of central vein catheter insertion because there was no evidence of disconnection of the central line or air infusion, and the patient underwent no invasive procedures that may have resulted in air embolism since the date of central vein catheterization. Arterial puncture was not done during the procedure. The patient's very poor general condition and the nondominant hemispheric lesion may have been partly responsible for the delayed detection of neurological changes in this case.

At that time of catheterization, the patient was in a hypovolemic state, and was therefore more susceptible to air embolism (2, 8). Chest CT scan revealed air remnant in the right atrium and his TEE also showed right-to-left shunt without definite intracardiac shunt. Therefore, we presumed that our patient had paradoxical cerebral air embolism related to central vein catheterization. The possible mechanism of paradoxical cerebral air embolism in our patient is as follows. First, patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease had greater anatomical intrapulmonary shunting than normal subjects (14). Our patient had right fibrothorax associated with tuberculosis sequelae and poor lung function. Therefore, we assumed that the influx of massive air into the arterial system may occur via intrapulmonary shunt in the disrupted lung. Second, if the filter function of the pulmonary capillary network is overloaded due to excessive entry of air, the air will pass into the left heart and the systemic arterial circulation (11, 12). Third, TEE cannot exclude the presence of undetectable small intracardiac shunt, such as patent foramen ovale (15).

The primary aims of treatment are identification of the source of air entry and prevention of further air embolization (2, 12). Initial general ICU measures should be performed as soon as possible, including oxygen supply and cardiopulmonary resuscitation. Hyperbaric oxygen therapy in special centers is recommended; however, its real efficacy has recently been called into question (3). General guidelines for preventing air embolism must be put in place, such as the Trendelenburg position, occlusion of the needle, adequate central venous catheter care, and occlusive dressing after removal (12).

In conclusion, neurological deterioration in a patient with central venous catheterization should always be taken as a potential sign of cerebral air embolism, prompting diagnosis and adequate treatment for minimization of further cerebral damage.

Figures and Tables

Fig. 1

Brain MRI. Diffusion-weighted brain MR imaging (A) demonstrated diffuse hyperintensity involving the whole of the right cerebral hemisphere, which was seen as an area of low signal intensity suggesting acute infarction on the apparent diffusion coefficient map (B). Numerous air bubbles (arrows) were seen within the infarct region.

Fig. 2

Immediate non-contrast brain CT showed an extensive lesion with low attenuation as well as air bubbles (arrows) in the right cerebral hemisphere.

References

1. Scott WL. Complications associated with central venous catheters. A survey. Chest. 1988. 94:1221–1224.

3. Layon AJ. Hyperbaric oxygen treatment for cerebral air embolism - where are the data? Mayo Clin Proc. 1991. 66:641–646.

4. Turnage WS, Harper JV. Venous air embolism occurring after removal of a central venous catheter. Anesth Analg. 1991. 72:559–560.

5. Black M, Calvin J, Chan KL, Walley VM. Paradoxic air embolism in the absence of an intracardiac defect. Chest. 1991. 99:754–755.

6. Mennin P, Coyle CF, Taylor JD. Venous air embolism associated with removal of central venous catheter. BMJ. 1992. 305:171–172.

7. Boer WH, Hene RJ. Lethal air embolism following removal of a double lumen jugular vein catheter. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 1999. 14:1850–1852.

8. Vesely TM. Air embolism during insertion of central catheters. J Vasc Interv Radiol. 2001. 12:1291–1295.

9. Teichgräber UK, Benter T. Air embolism after the insertion of a central venous catheter. N Engl J Med. 2004. 350.

10. Peters JL, Armstrong R. Air embolism occurring as a complication of central venous catheterization. Ann Surg. 1978. 187:375–378.

11. Ploner F, Saltuari L, Marosi MJ, Dolif R, Salsa A. Cerebral air embolism with use of central venous catheter in mobile patient. Lancet. 1991. 338:1331.

12. Heckman JG, Lang CJ, Kindler K, Huk W, Erbguth FJ, Neundorfer B. Neurologic manifestations of cerebral embolism as a complication of central venous catheterization. Crit Care Med. 2000. 28:1621–1625.

13. Hinkle DA, Raizen DM, McGarvey ML, Liu GT. Cerebral air embolism complicating cardiac ablation procedures. Neurology. 2001. 56:792–794.

14. Miller WC, Heard JG, Unger KM. Enlarged pulmonary arteriovenous vessels in COPD. Another possible mechanism of hypoxemia. Chest. 1984. 86:704–706.

PDF

PDF ePub

ePub Citation

Citation Print

Print

XML Download

XML Download