Abstract

Pleural effusion in chronic myeloid leukemia (CML) is poorly understood and rarely reported in the literature. When the pleural effusion is caused by leukemic pleural infiltration, the differential white blood cell count of the effusion is identical to that of the peripheral blood, and the fluid cytology reveals leukemic blasts. We report here a case of bilateral pleural involvement of atypical CML in an 83-yr old male diagnosed with pancreatic cancer with abdominal wall metastasis and incidental peripheral leukocytosis. Based on bone marrow examination, chromosome analysis and polymerase chain reaction he was diagnosed with Philadelphia chromosome negative, BCR/ABL gene rearrangement negative CML. Following 3 months of treatment with gemcitabine for pancreatic cancer, he developed bilateral pleural effusions. All stages of granulocytes and a few blasts were present in both the pleural fluid and a peripheral blood smear. After treatment with hydroxyurea and pleurodesis, the pleural effusion resolved.

Atypical chronic myeloid leukemia (CML) is negative for both the Philadelphia chromosome and BCR/ABL gene rearrangement (1). During the course of CML, 37% of patients develop extramedullary disease in sites such as the lymph nodes, spleen, or meninges (2), but, pleural effusion due to leukemic infiltration in this disease is rare. In this paper, we describe a patient who developed pleural effusion during treatment for atypical CML and pancreatic cancer. The pleural effusions were cleared after treatment with hydroxyurea and pleurodesis.

An 83-yr-old male patient with leukocytosis was admitted to our hospital on September, 2004. His medical history included an early gastric cancer and distal gastrectomy in 1989, and a right lobectomy for non small cell lung cancer in May 2004. One month prior to the admission, he was diagnosed as having pancreatic tail cancer with abdominal wall metastasis, which had not been treated surgically or with chemotherapy.

On physical examination, the patient's liver and spleen were not palpable. A tender and firm mass, measuring 1×2 cm, was noted on the periumbilical abdominal wall. Hematologic findings were Hb 10.6 g/dL, WBC 71×109/L (neutrophil 58%, lymphocyte 7%, monocyte 13%, eosinophil 3%, promyelocyte 2%, myelocyte 10%, metamyelocyte 4%, blast 1%, normoblast 1/100 WBC), and platelet 192×109/L. Pathologic examination showed that his palpable abdominal wall mass was a metastatic adenocarcinoma that differed from the previous non small cell lung cancer. Immunohistochemically, the tumor cells were positive for cytokeratin 7 (CK7) and negative for thyroid transcription factor 1 (TTF-1) and cytokeratin 20 (CK20), whereas his non small cell lung cancer cells had been positive for TTF-1 and CK7 and negative for CK20. Bone marrow examination showed hypercellular marrow (cellularity 90%) containing cells at all stages of granulocytic hyperplasia and 0.6% blasts. There were some hypogranular myelocytes, indicating dysgranulopoiesis (Fig. 1). Polymerase chain reaction for BCR/ABL fusion gene was negative. The leukocyte alkaline phosphatase (LAP) activity score was 13 (reference range 30-130). Computed tomography of the abdomen showed a solid mass in the tail of the pancreas with attachment to the spleen and invasion of the spleen and splenic artery by the mass, leading to splenic infarction (Fig. 2). Based on these results, he was diagnosed with atypical CML. He was treated with gefitinib 250 mg/day for metastatic pancreatic cancer and hydroxyurea 1,500 mg/day plus allopurinol for atypical CML. Treatment with hydroxyurea was interrupted intermittently when WBC count of the peripheral blood decreased to 10×109/L or less. Beginning in November 2004, he was treated with gemcitabine for pancreatic cancer, interrupted periodically because of infectious diarrhea, acute renal failure due to use of aminoglycoside antibiotics and skin rash. At that time, treatment with hydroxyurea was stopped due to thrombocytopenia.

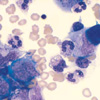

After 3 months of treatment with gemcitabine, the patient experienced progressive dyspnea and fatigue, as well as being tachypneic (30/min) and pale. Pulmonary examination revealed decreased bilateral breathing sounds and chest radiograph showed bilateral pleural effusion (Fig. 3). Right thoracentesis was performed and 1,400 mL of serous fluid was aspirated. Analysis of the pleural fluid showed glucose 109 mg/dL, protein 2.2 g/dL (serum protein 4.6 g/dL), albumin 1.1 g/dL (serum albumin 2.0 g/dL), LDH 386 IU/L (serum LDH 1,064 IU/L, reference range 120-250 IU/L), adenosine deaminase 23U/L, hematocrit 6.0%, WBC count 2,390 /µL (neutrophil 51%, lymphocyte 19%, histiocyte 9%, band form 6%, promyelocyte 3%, myelocyte 5%, metamyelocyte 5%, normoblast 3/100 WBC, blast 2%) (Fig. 4). Hematologic findings of the peripheral blood were Hb 8.7 g/dL, WBC 150×109/L (neutrophil 62%, lymphocyte 7%, monocyte 5%, promyelocyte 2%, myelocyte 18%, metamyelocyte 5%, blast 0%, normoblast 1/100 WBC), platelet 109×109/L. The ratio of erythrocytes to nucleated cells in the effusion was 8 as compared to a ratio of 18 in the blood, suggesting that the nucleated cells in the effusion were not solely due to bleeding into the pleural cavity. The pleural fluid was negative for Gram stain and acid fast bacilli. The patient was diagnosed with CML complicated with pleural effusion. Bilateral chest drainage catheters were inserted to control the pleural effusion. The patient was retreated with hydroxyurea and allopurinol, and the amount of pleural fluid decreased in accord with the decrease in the WBC count of peripheral blood. Due to loculated pleural effusion, however, the effusion did not completely resolve. At this point, a right chest tube was substituted for the right chest drainage catheter. Pleurodesis was performed for the right pleural effusion, thus relieving dyspnea of the patient. Two months after the appearance of the pleural involvement, the patient died due to hypercarbic respiratory failure. Until that time, however, no peripheral blood blast crisis was detected.

Development of extramedullary disease in the pleura of patients with CML is frequently accompanied by increased blasts in the pleural fluid. Analysis of pleural fluid, however, does not always show excess blasts, and in some cases, all stages of granulocytes and a few blasts are found in the pleural fluid or ascites (9, 11). Categorization of the cytomorphologic features of extramedullary diseases in 18 patients with CML showed that extramedullary disease could be sorted into 3 types, depending on the proportion of blasts to more mature differentiated granulocytic cells (6). These 3 categories were blastic, showing a predominance of blasts (5 patients, 28%); immature, showing a predominance of blasts and other nonblastic myeloid precursors (8 patients, 54%); and mature, with a full spectrum of granulocytic maturation from blasts to granulocytes (5 patients, 28%).

The patient described here had serous pleural effusion after 3 months of treatment with hydroxyurea and gemcitabine. Because he had multiple malignancies and the pleural fluid was an exudate, we hypothesized that the pleural effusion of the patient was caused by his malignancies. Pleural fluid cytology, however, showed no evidence of gastric, lung or pancreatic cancer cells but revealed premature and mature leukocytes, and variable numbers of blasts. We therefore regarded the pleural effusion of the patient as related to CML.

There are several possible mechanisms of exudative pleural effusion in CML patients. The first mechanism is leukemic infiltration into the pleura, which usually occurs at the time of or just prior to bone marrow evolution to blast crisis phase (2, 3). The most common sites are the lymph nodes, bone and nervous system, while infiltration of the brain, testis, skin, breast, soft tissues, synovia, gastrointestinal tract, ovaries, kidneys and pleura occur less frequently (4). Involvement of the pleura has been rarely documented, and isolated pleural blast crisis in the absence of medullary transformation is extremely rare (2). In these cases, pleural fluid analysis revealed variable stages of granulocytes and leukemic blasts.

The second mechanism is pleural reaction secondary to bleeding into the pleural cavities that may cause pleural effusion in the patient with CML (5). Predisposing factor such as leukostasis and platelet dysfunction may have a role in hemorrhagic effusion. Thus, the cytologic findings in the effusion are due to leukemic cell contamination and pleural reaction as a result of bleeding into the pleural cavity. If this is true, the ratio of red blood cells to nucleated cells in the blood and effusion should be similar. In our patient, however, the ratio of red blood cells to nucleated cells was higher in the blood than in the pleural effusion, and thus it is more likely that the large numbers of nucleated cells in the pleural fluid originated from the pleural cavities.

A third possible mechanism underlying effusion is pleural extramedullary hematopoiesis. It can present as a discrete mass in almost any organ, including the liver, spleen, breasts, lymph nodes, kidneys, thyroid, pancreas, endometrium, and mediastinum, or in the serous effusion. But, unlike pleural leukemic infiltration, extramedullary hematopoiesis includes hematopoietic cells of the erythroid, myeloid, and megakaryocytic cells, although one lineage can predominate (6). A fourth mechanism causing effusion is nonmalignant causes, such as infection. Therefore, the possibility of infectious process must be excluded and the presence of necrotic debris and/or the positive identification of microorganisms by special stains may suggest an infectious process.

Based on a review of the literature and clinical findings, leukemic infiltration into pleura was suggested as the cause of pleural effusion in our patient.

Generally the median time from diagnosis of extramedullary blast crisis to marrow blast crisis is 4 months, and the median survival after development of extramedullary transformation is 5 months (4). Extramedullary disease in CML is considered an indicator of poor prognosis, which should lead to a change in therapy and to the institution of treatments usually reserved for blast crisis (4). Unfortunately, however, there is no effective standard therapy for pleural effusion in CML. To the best of our knowledge, there have been only 8 case reports of isolated pleural infiltration of CML (2-4, 7-10). One patient responded to thoracentesis and treatment with hydroxyurea without recurrence (9), and another patient responded to systemic chemotherapy with idarubicin and Ara-C (10). In 5 patients, in which pleural blast antedated hematological transformation, intrapleural infusion of chemotherapeutic agents (methotrexate, cytosine arabionside, prednisone) and systemic chemotherapy were ineffective, and all 5 patients died within 2 months (3, 4, 7, 8). In the remaining patient, the type of treatment was not reported (2).

In conclusion, patients with CML should be considered at risk for development of extramedullary manifestations of blast crisis while the bone marrow remains in the chronic phase. Extramedullary blast crisis of CML can occur at any time and anywhere circulating stem cells are found. In CML patient with pleural effusions, bleeding into pleural cavity and extramedullary hematopoiesis should first be considered. If these causes are ruled out, the presence of leukemic cells in the effusion may denote leukemic involvement of pleura. Pleural infiltration of CML adversely affects prognosis.

Figures and Tables

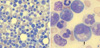

Fig. 1

(A) Smear of marrow aspirate showing increased numbers of granulocytes at all stages of development and blasts (Wright-Giemsa stain, ×400). (B) Smear of marrow aspirate showing hypogranular myelocytes (arrow) (Wright-Giemsa stain, ×1,000).

References

1. Misialek MJ, Pechet L. A diagnostic dilemma: chronic myelomonocytic leukemia versus atypical chronic myeloid leukemia. A case report and review of the literature. Acta Haematol. 1997. 98:221–227.

3. Yam LT. Granulocytic sarcoma with pleural involvement. Identification of neoplastic cells with cytochemistry. Acta Cytol. 1985. 29:63–66.

4. Sacchi S, Temperani P, Selleri L, Zucchini P, Morselli S, Vecchi A, Longo R, Torelli G, Emilia G, Torelli U. Extramedullary pleural blast crisis in chronic myelogenous leukemia: cytogenetic and molecular study. Acta Haematol. 1990. 83:198–202.

5. Janckila AJ, Yam LT, Li CY. Immunocytochemical diagnosis of acute leukemia with pleural involvement. Acta Cytol. 1985. 29:67–72.

6. Suh YK, Shin HJ. Fine-needle aspiration biopsy of granulocytic sarcoma: a clinicopathologic study of 27 cases. Cancer. 2000. 90:364–372.

7. Vilpo JA, Dryzun B, Klemi P, Lassila O, de la Chapelle A. Extramedullary pleural blast crisis during otherwise chronic phase in chronic granulocytic leukaemia. Eur J Cancer. 1980. 16:885–891.

8. Scully RE, Galdabini JJ, McNeely BU. Case records of the Massachusetts General Hospital. Weekly clinicopathological exercises. Case 24-1976. N Engl J Med. 1976. 294:1333–1339.

9. Mohapatra MK, Das SP, Mohanty NC, Dash PC, Bastia BK. Haemopericardium with cardiac tamponade and pleural effusion in chronic myeloid leukemia. Indian Heart J. 2000. 52:209–211.

PDF

PDF ePub

ePub Citation

Citation Print

Print

XML Download

XML Download