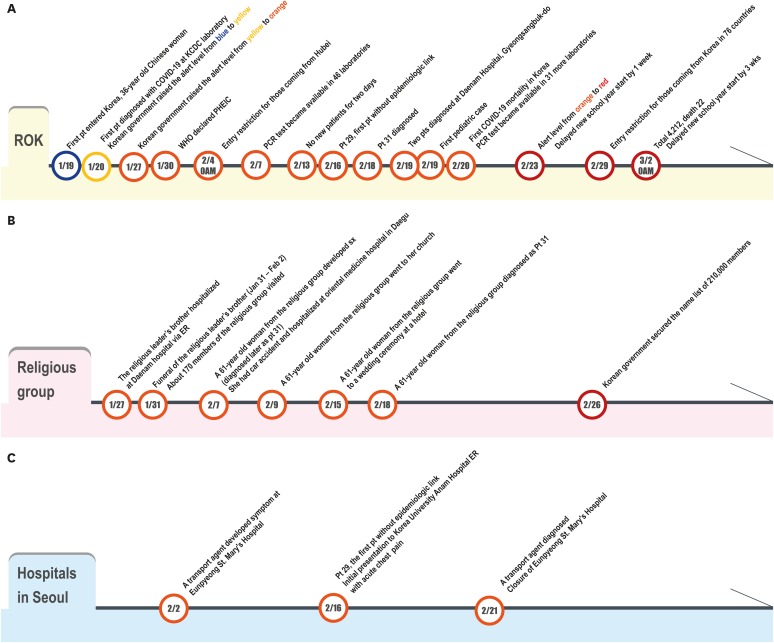

TIMELINE OF COVID-19 OUTBREAK IN KOREA

Fig. 1A shows the timeline of significant events in Korea since January 19, 2020, when the first confirmed case with Chinese nationality entered Korea from Wuhan, China.12 Since the first case, the sources of infection could be traced by contact investigation until the patient 29. The patient 29 was the first patient identified in Seoul and did not have an epidemiological link or travel history to China. From this patient, the possibility of community transmission was raised. The first pediatric case (patient 32) was diagnosed on February 18, 2020.3 The first fatal case occurred on February 20, 2020. As the numbers of confirmed cases were rapidly increasing, the Korean government raised the alert level from orange to red on February 23 and the Ministry of Education delayed the new school year opening by one week on February 23, 2020 and currently ordered all school closures. As of February 29, 76 countries banned Koreans from entering their countries.4

Fig. 1

Timeline of COVID-19. (A) Whole country of Republic of Korea. (B) Religious group in Daegu and Gyeongsangbuk-do. (C) Hospital exposure in Eunpyeong St. Mary's Hospital and the Korea University Anam Hospital emergency room in Seoul.

Patient 31 was the first case related to the religious group. Daenam Hospital has a mental ward where many casualties occurred.

ROK = Republic of Korea, Pt = patient, COVID-19 = Coronavirus disease-19, KCDC = Korea Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, WHO = World Health Organization, PHEIC = Public Health Emergency of International Concern, PCR = polymerase chain reaction, ER = emergency room, sx = symptom.

Laboratory test for COVID-19 was initially performed at the Korea Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (KCDC) and the test became available at 17 regional laboratories (Public Health and Environment Research Institute) on January 24 throughout the nation.5 Since February 7, the test facilities were expanded to 46 laboratories including tertiary hospitals6 and more test centers were added later.

Fig. 1B shows the timeline of the events related to a religious group called Shincheonji that contributed to the explosive outbreak in the city of Daegu and Gyeongsangbuk-do (North Gyeongsang Province). On January 27, 2020, a brother of the leader of this religious group was hospitalized in Daenam Hospital in Cheongdo, a town which is 27 km from Daegu. His brother died on January 31, and they had a funeral ceremony for two nights and three days from January 31 to February 2 in a hospital funeral home located in Daenam Hospital. Because this was the funeral service of the leader's family, many members (about 170) of the religious group visited the hospital funeral home for 3 days. A 61-year-old woman from this religious group who visited the funeral was later confirmed with COVID-9 on February 23. Of note, she lived in Daegu and occasionally commuted to Seoul. Tracing her movements, KCDC found that she attended two worship services at the Shincheonji Church in Daegu with at least 1,000 other members of her religious group.

Fig. 1C shows the timeline of the confirmed case in a patient transporter who worked at the Eunpyeong St. Mary's Hospital with over 800 beds located in northern Seoul. A 35-year-old man developed symptoms of COVID-19 on February 2 and transported several patients from February 2 to February 17 before he quit his job at the hospital. A total of 302 were identified as his contacts and out of 262 patients he transported, 187 patients have already discharged from the hospital and 75 patients were still in the hospital.7 As a result, the hospital has been closed and 14 additional patients were confirmed from this hospital as of March 2, 2020.

EPIDEMIOLOGICAL CHARACTERISTICS OF COVID-19 OUTBREAK IN THE REPUBLIC OF KOREA

Numbers of confirmed cases and tests in major cities and provinces

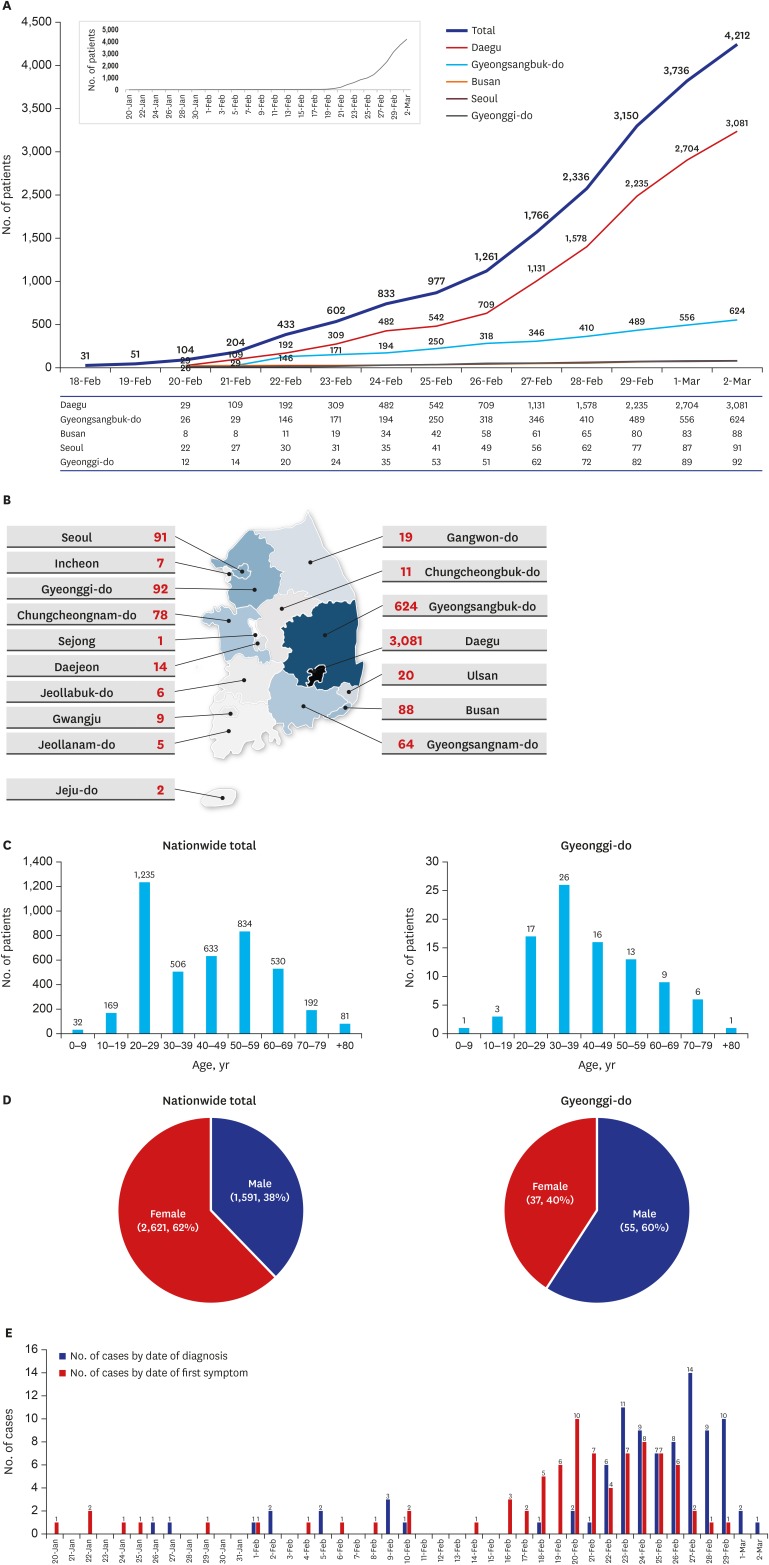

Fig. 2A shows the cumulative confirmed cases with COVID-19 (total, three major cities, and two major provinces). The cumulative number has increased dramatically since February 18, 2020, after the identification of patient 31. Fig. 2B shows the national distribution of the confirmed cases in Korea.

Fig. 2

Number of confirmed patients with COVID-19 by March 2, 2020. (A) Cumulative frequency curve in the Republic of Korea and selected cities and provinces. (B) Number of confirmed cases with COVID by locations in ROK. (C) Age distribution in whole ROK (left) and in Gyeonggi-do (right) (D) Sex distribution of confirmed cases in the nation (left) and Gyeonggi-do (right) (number, %). (E) Epidemic curves of COVID-19 patients in Gyeonggi-do, Korea.

Province and city-specific numbers of patients have been reported since February 20, 2020.

The numbers in the table at the bottom of the figure represent the number of cases in each specific location on each date from February 20 to March 2, 2020.

ROK = republic of Korea, COVID-19 = Coronavirus disease-19.

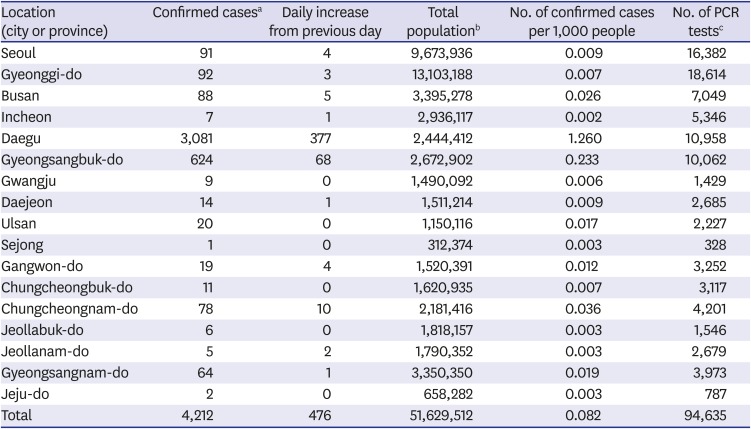

Table 1 shows the total number of cases in major cities and provinces. It also shows the positive cases per 1,000 persons, and the number of laboratory tests performed to diagnose the reported cases. Daegu has the highest number, with 1.26 cases per 1,000 persons as of March 2, 2020. The number of tests performed were highest in two major cities (16,382 tests in Seoul with a positive rate of 0.6% and 10,958 tests in Daegu with a positive rate of 28.1%) and two major provinces (18,614 tests in Gyeonggi-do with a positive rate of 0.5% and 10.062 tests in Gyeonsangbuk-do with a positive rate of 6.2%).8

Table 1

The number of confirmed cases and laboratory tests in major cities and provinces (-do) in the Republic of Korea

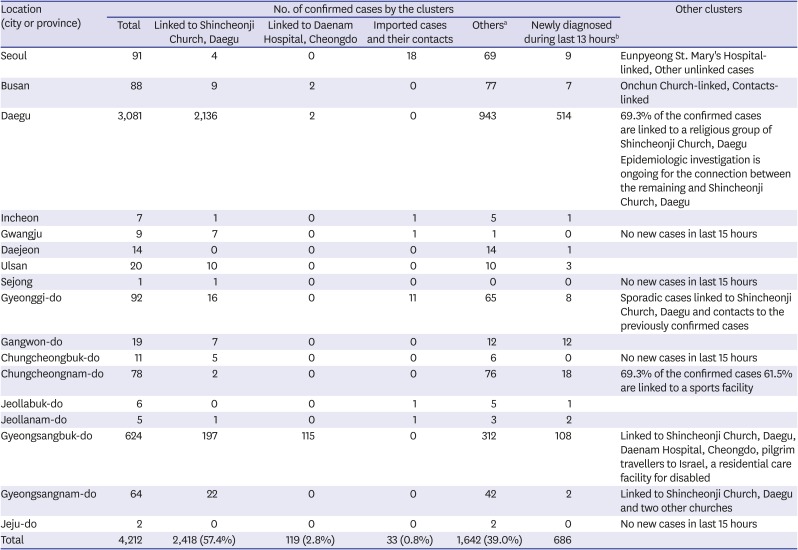

Number of confirmed cases linked to major clusters by the cities and provinces

Since there were several major clusters for potential spread, confirmed cases were classified according to the exposure source when possible. Table 2 shows the total number of confirmed cases in major cities and provinces and the clusters in those locations.9

Table 2

The total number of confirmed cases and cases linked to major clusters by the cities and provinces in the Republic of Korea

Based on the report and the data assigned with the control number from the Korea Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Thus, it may be different from those collected from the local governments. It can also be changed according to the results from the epidemiological investigations.

aIndividual sporadic cases or cases under investigation; bBased on the reported cases to the Korea Centers for Disease Control and Prevention between 9 am March 1 and 0 am March 2.

The data may differ from previously published due to changes in jurisdictions between announcement times.

The largest cluster was the Shincheonji religious group related cluster in Daegu and Gyeonsangbuk-do area. In Daegu, almost 70% of the cases were related to this religious group. The second-largest cluster was the Daenam Hospital in Gyeonsangbuk-do where many patients in the closed psychiatric wards were infected.

Age and sex distribution

Fig. 2C and D show the age and sex distribution. In total confirmed cases, the age distribution showed M shape with two peaks in the age group of the 20s and 50s. Among the confirmed cases in Gyeonggi-do where the third-highest number of patients was observed, the peak age group was the 30s with a bell-shaped distribution. Of note, Chinese data showed that most patients were in their 30–60s.10

For the sex ratio, only 37.7% were male in total confirmed cases. However, among the confirmed cases in Gyeonggi-do, 59.1% were male. In Chinese data, 51% were male.11 Therefore, there may not be any increased susceptibility for COVID-19 among certain age groups or sex. The distribution may reflect the movement and the social activities of individuals in different societies. In the Korean situation, predominance by the age group of the 20s and females may have caused by the outbreak related to a religious group in Daegu.

Epidemic curve (Symptom-onset-date-based vs. diagnosis-date-based)

Fig. 2E shows that the symptom-onset-date-based epidemic curve was followed by the diagnosis-date-based epidemic curve in Gyeonggi-do. From the peak of the symptom-onset-based epidemic curve (around February 20) to the peak of the diagnosis-based epidemic curve (February 27) was about 7 days. In the Chinese report, from the peak of the symptom-onset-based epidemic curve (around January 24) to the peak of the diagnosis-based epidemic curve (February 4) was about 10 days.11

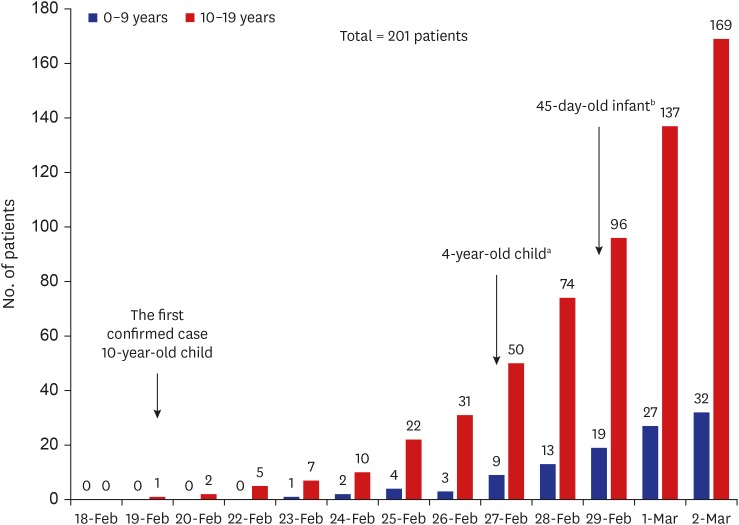

PEDIATRIC POPULATION

The proportion of children (≤ 19 years) is 18% of the total population of Korea.12 Therefore, COVID-19 in this age group also needs attention.

Since the diagnosis of the first pediatric case on February 19, 2020,3 the number of pediatric cases (≤ 19 years) gradually increased and 201 children were confirmed with COVID-19 as of March 2, 2020. The first pediatric case in Korea was a 10-year old girl who was exposed sequentially to the confirmed family members (a relative and her mother). Fig. 3 shows the cumulative pediatric cases from February 10 to March 2, 2020. The proportion of pediatric cases (≤ 19 years) was 4.8% of total confirmed cases (32 children in 0–9 years old age group, 169 children in 10–19 years old age group).8 Among all pediatric cases (≤ 19 years), the proportion of younger children (0–9 years old) was 15.9%. Of note, there was a 4-year old boy who attended the daycare center before the confirmation. Identifying the transmission pattern in young children requires more data.13 As of March 2, the youngest pediatric case with COVID-19 in Korea was a 45-day old male baby who was infected by his father, a member of the religious group. Most pediatric patients are in mild clinical conditions.

Fig. 3

Cumulative pediatric cases in the Republic of Korea as of March 2, 2020.

aThe child was presumed to have been infected by a familial exposure. He attended the daycare center one day before the symptom onset; bThe youngest pediatric case as of March 2, 2020.

More detailed data are required on the clinical manifestation of the children and the roles of infected children on the epidemiology of COVID-19 in the community.

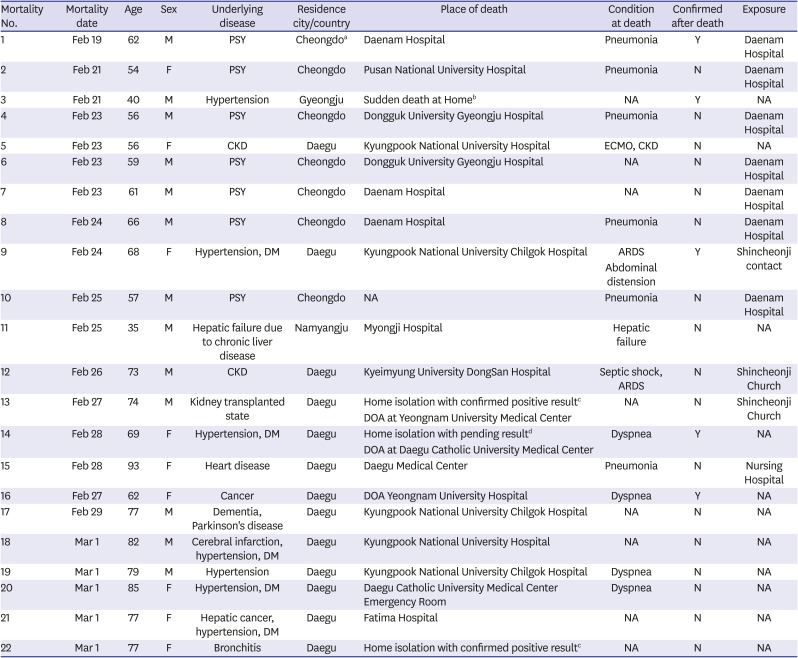

MORTALITY

On March 2, of 4,212 confirmed cases, 22 patients have died (0.5%) and 13 patients were male (59.1%). Table 3 shows a detailed description of deceased patients.8 Out of 22 patients, 20 patients (20/22, 90.9%) were 50 or older (Fig. 4). The case fatality rate increased with older age. The case fatality rate of persons 50 years or older was higher than that of persons younger than 50 years (1.2% vs. 0.2%, P = 0.0017, Fishers exact test).

Table 3

Mortality in Korean patients with Coronavirus disease-19 as of 0 am, March 2, 2020

Age distribution: 30–39 years (1/22, 4.5%), 40–49 years (1/22, 4.5%), 50–59 years (5/22, 22.7%), 60–69 years (6/22, 27.3%), 70–79 years (6/22, 27.3%), over 80 years (3/22, 13.6%).

NA = not available, PSY = psychiatric disorder, CKD = chronic kidney disease, ECMO = extracorporeal membrane oxygenation, DM = diabetes mellitus, ARDS = acute respiratory distress syndrome, DOA= dead on arrival.

aCheongdo is a county, 27 km from Daegu in Gyeongsangbuk-do (North Gyeongsang Province); bHe died at home suddenly; cThey died while waiting for admission with the confirmed result; dShe died while waiting for the pending result.

All of fatal patients had underlying conditions. Among them, seven patients (7/22, 31.8%) were from the psychiatric ward of Daenam Hospital, where they had been hospitalized for several years in poor general conditions. The youngest patient was a 35-year old Mongolian patient. He was already in a serious condition from chronic hepatic failure with cirrhosis and esophageal variceal bleeding. A 40-year old male with hypertension died suddenly, was found the next morning by a coworker, diagnosed with COVID-19 later. Including this patient, the diagnosis was made after death in five patients (5/22, 22.7%). One patient (mortality number 3) died at home suddenly, the rest of the three patients died during hospitalization (mortality numbers 1, 9, and 16), and one patient (mortality number 14) died at home while waiting for the pending test result. Of note, two patients (mortality numbers 13 and 22) were at home isolation with positive results waiting for the hospitalization, but their condition aggravated rapidly and they died. Three patients (mortality numbers 13, 14, and 16) died on arrival at the hospital.1415 Therefore, even though most of COVID-19 patients may have mild clinical courses, individuals with old age and/or underlying medical conditions should be carefully monitored.

CONCLUSION

COVID-19 is a novel threatening viral infection to human society. An exponential increase in numbers of COVID-19 patients in Korea appeared to be mainly caused by exposure among the members of a religious group with the additional community- and hospital-transmission. The transmission exploded mainly in Daegu and neighboring areas. With this sudden and massive increase in confirmed cases, there is an urgent need and preparation for treatment strategies for serious or critical patients. Also, plans and actions for mild cases should properly proceed.

Furthermore, increasing cases without epidemiologic links in the parts of the nation may herald the risks for additional cluster outbreaks in the coming weeks. Monitoring for such potential clusters of the outbreak are needed, and countermeasures should be urgently prepared.

Koreans should remain calm and vigilant and continue to be socially responsible. The government, the health authority, experts in the field, and all Koreans should cooperate to overcome this challenging outbreak with a prompt and dynamic response.

PDF

PDF Citation

Citation Print

Print

XML Download

XML Download