Abstract

A 67-year-old lady was managed with percutaneous cholecystostomy for severe acute cholecystitis with septic shock. An interval laparoscopic subtotal cholecystectomy was done at 8 weeks. Her post-operative phase was complicated by intra-abdominal abscess requiring radiologically guided percutaneous drain insertion. Five days following the removal of the drain, she presented with a right abdominal wall abscess. A computerized tomography scan showed an abdominal wall ectopically-retained gallstone. The gallstone was retrieved along with drainage of abscess.

Laparoscopic cholecystectomy (LC) is the gold standard treatment for symptomatic gallstones. Stone spillage is one of the hazard during cholecystectomy. Retained gallstones, whether in intra- or extra-peritoneal cavities, are a nidus for sepsis. Previous reports document the presentation of intra-peritoneal and abdominal wall abscesses secondary to retained stones, after largely uncomplicated LC.123 Abdominal wall abscesses account for approximately 14% of the complications from retained stones and almost all are reported along the port / surgical incision sites.3 In this case, we report a retained stone presenting as an abdominal wall abscess in an artificially created tract of a previous percutaneous drain, following its removal.

The patient was 67-year-old woman was admitted with right upper abdominal pain over the past four days. Her comorbidities included hypertension, hyperlipidemia, type 2 diabetes mellitus and a previous history of severe acute cholecystitis (AC) complicated by septic shock that was managed with a percutaneous cholecystostomy (PC) and critical organ support. She was planned for an interval cholecystectomy 8 weeks later. Due to the dense adhesions affecting safe dissection of the hepatocystic triangle, a fenestrated laparoscopic subtotal cholecystectomy (SC) was performed.

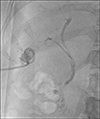

Her post-operative phase was complicated by a collection in the gallbladder fossa measuring 1.1×1.2 cm with no clear visualization of gallstones within or adjacent to the collection on computerized tomography (CT) scan imaging. The collection was managed with an ultrasound guided insertion of an 8 French pigtail catheter (Navarre®; Bard Biopsy Systems, Tempe, AZ, USA). Bacteriology from the fluid drained revealed Citrobacter koseri, Klebsiella variicola and Enterococcus fecalis as well as anaerobes. A course of amoxicillin and clavulanic acid was completed according to sensitivity testing. A dye study of drain showed contrast opacification of the biliary tree without retained biliary stones and a prompt duodenogram. (Fig. 1). This biliary leak was low in volume and eventually resolved spontaneously. The pigtail catheter was then removed according to the local protocol of managing abdominal drains that include clinical progress, serum biochemistry, drainage volume and imaging features.45

Five days following removal of the pigtail drainage catheter, the patient returned to the emergency department with symptoms of local pain and pus discharge from the skin puncture site. Serum biochemistry revealed elevated total white cell count with normal renal and liver function. A CT of the abdomen revealed two sub-centimeter hyperdensities within 2.1×3.2 cm subcutaneous collection of fluid (Figs. 2, 3). This was an unexpected finding, given that there were no intra-peritoneal gallstones seen on the post-operative CT. Regardless, a diagnosis of ectopic retained gallstones was made and a surgical drainage performed. Two stones were retrieved by incision and drainage of the subcutaneous abscess. There was no extension of abscess cavity into the peritoneum. Intra-operative bacteriology demonstrated polymicrobial growth including gram negative and anaerobic organisms. The patient was discharged on post-operative day one with a course of oral antibiotics.

Spillage of gallstones is a known complication of laparoscopic cholecystectomy (LC). A retrospective review of six studies described an incidence of spilled gallstones in 7.3% of LC with iatrogenic gallbladder perforation, with over 2.4% of these gallstones not retrieved.3 However, complications from retained stones are reported to occur in only 0.08% to 0.3% of all cholecystectomies.6 Hence a retained gallstone and its sequelae are rare phenomena in clinical surgery. Further, of all the complications arising from retained stones, only 14% are abdominal wall abscesses making them even rarer and hence reportable.3

Percutaneous cholecystostomy (PC) is an established treatment for severe AC; especially in patients with comorbidities that impact the surgical risk.4 These patients may subsequently undergo interval cholecystectomy, albeit with varying but significant levels of difficulty.7 Deviant anatomy, disturbed pathology and dangerous surgery are typical factors indicating high-risk operation. In patients with severe AC and PC; some surgeons argue against recommendation of eventual cholecystectomy due to these difficulties and associated risk.89 Such arguments against eventual cholecystectomy are further supported in a frail and elderly patient, with poor quality of life following major surgery and in future if recurrent cholecystitis develops, that episode can also be managed non-operatively. We recommend eventual definitive cholecystectomy for all patients and only those patients who decline surgery or who have prohibitive risk are not offered. In our experience of managing patients with PC, estimated half of the patients are recommended eventual definitive cholecystectomy.4 The difficulty of laparoscopic removal of the gallbladder is attributed to dangerous pathology in these instances which typically results from adhesions around the gallbladder and inability to dissect the Calot's triangle to obtain critical view.7 Not surprisingly, many surgeons advocate upfront open cholecystectomy or advise high-risk patients for open conversion in such instances. We routinely offer laparoscopic approach to all our patients and advise higher-risk patients to consider subtotal cholecystectomy or open conversion. A surgeon may opt to convert the operation to an open cholecystectomy or to proceed with a subtotal cholecystectomy depending on his experience, anatomical and pathological factors and resources.7 A subtotal cholecystectomy is achieved by dissection at the Hartman's pouch, leaving behind a part of the Hartmann's pouch with the cystic duct. This may lead to gallstone spillage in the peritoneal cavity requiring manual evacuation of these stones. It is a good practice to place a retrieval bag at this phase of surgery preemptively to bag the stones so as not to miss to recollect them later. Retained gallstones can lead to intra-abdominal collection.3 Such collections can form in sub hepatic and subphrenic spaces intra-peritoneally and at port sites extra-peritoneally.3

Grass et al.1 described a case report wherein a patient with a previous history of LC presented with a periumbilical swelling. An imaging study confirmed a retained stone and collection at the umbilical port site which was removed surgically. Our patient differs from the previously published case reports in that the retained gallstones formed a subcutaneous abscess along the percutaneously inserted drain site. It is possible that persistent efforts to aspirate the contents of intra-abdominal collection could have sucked the retained intra-peritoneal gallstone to migrate to subcutaneous site. Following the removal of this drain, the right abdominal abscess had formed beneath the exit site of the drain. This hypothesis was further validated by bacteriologic reports showing gram negative and anaerobic organisms from the abdominal wall collection. Source control was achieved, stones were removed and a short course of oral antibiotics was prescribed upon discharge, in line with recommendations from an established anti-microbial stewardship program.10

This case highlights a few important points. Firstly, it is imperative to carefully and meticulously remove all spilled gallstones, especially in patients with subtotal cholecystectomy. Secondly, in abdominal collections following cholecystectomy, the possibility of a retained gallstone should hold an index of suspicion. This is important as gallstones are not radio-opaque. Lastly, once a retained stone is detected, retrieval is indicated. To our knowledge, ours is the first report of an abdominal wall ectopic gallstone in the percutaneous drain site tract.

Figures and Tables

Fig. 1

Dye study of percutaneous drain showing biliary tree opacification with duodenogram and no retained stones.

References

1. Grass F, Fournier I, Bettschart V. Abdominal wall abscess after cholecystectomy. BMC Res Notes. 2015; 8:334.

2. Hand AA, Self ML, Dunn E. Abdominal wall abscess formation two years after laparoscopic cholecystectomy. JSLS. 2006; 10:105–107.

3. Woodfield JC, Rodgers M, Windsor JA. Peritoneal gallstones following laparoscopic cholecystectomy: incidence, complications, and management. Surg Endosc. 2004; 18:1200–1207.

4. Yeo CS, Tay VW, Low JK, Woon WW, Punamiya SJ, Shelat VG. Outcomes of percutaneous cholecystostomy and predictors of eventual cholecystectomy. J Hepatobiliary Pancreat Sci. 2016; 23:65–73.

5. Shelat VG, Chia CL, Yeo CS, Qiao W, Woon W, Junnarkar SP. Pyogenic liver abscess: does escherichia coli cause more adverse outcomes than klebsiella pneumoniae? World J Surg. 2015; 39:2535–2542.

6. Sathesh-Kumar T, Saklani AP, Vinayagam R, Blackett RL. Spilled gall stones during laparoscopic cholecystectomy: a review of the literature. Postgrad Med J. 2004; 80:77–79.

7. Amirthalingam V, Low JK, Woon W, Shelat V. Tokyo Guidelines 2013 may be too restrictive and patients with moderate and severe acute cholecystitis can be managed by early cholecystectomy too. Surg Endosc. 2017; 31:2892–2900.

8. Horn T, Christensen SD, Kirkegård J, Larsen LP, Knudsen AR, Mortensen FV. Percutaneous cholecystostomy is an effective treatment option for acute calculous cholecystitis: a 10-year experience. HPB (Oxford). 2015; 17:326–331.

9. Nasim S, Khan S, Alvi R, Chaudhary M. Emerging indications for percutaneous cholecystostomy for the management of acute cholecystitis--a retrospective review. Int J Surg. 2011; 9:456–459.

10. Sartelli M, Labricciosa FM, Barbadoro P, Pagani L, Ansaloni L, Brink AJ, et al. The global alliance for infections in surgery: defining a model for antimicrobial stewardship-results from an international cross-sectional survey. World J Emerg Surg. 2017; 12:34.

PDF

PDF ePub

ePub Citation

Citation Print

Print

XML Download

XML Download