1. Kontis V, Bennett JE, Mathers CD, Li G, Foreman K, Ezzati M. Future life expectancy in 35 industrialised countries: projections with a Bayesian model ensemble. Lancet. 2017; 389(10076):1323–1335. PMID:

28236464.

2. Baek JY, Lee E, Jung HW, Jang IY. Geriatrics fact sheet in Korea 2021. Ann Geriatr Med Res. 2021; 25(2):65–71. PMID:

34187140.

3. Feigin VL, Roth GA, Naghavi M, Parmar P, Krishnamurthi R, Chugh S, et al. Global burden of stroke and risk factors in 188 countries, during 1990–2013: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2013. Lancet Neurol. 2016; 15(9):913–924. PMID:

27291521.

4. Lopez AD, Mathers CD, Ezzati M, Jamison DT, Murray CJ. Global and regional burden of disease and risk factors, 2001: systematic analysis of population health data. Lancet. 2006; 367(9524):1747–1757. PMID:

16731270.

5. Kim HC, Lee H, Lee HH, Lee G, Kim E, Song M, et al. Korea hypertension fact sheet 2022: analysis of nationwide population-based data with a special focus on hypertension in the elderly. Clin Hypertens. 2023; 29(1):22. PMID:

37580841.

6. Fried LP, Tangen CM, Walston J, Newman AB, Hirsch C, Gottdiener J, et al. Frailty in older adults: evidence for a phenotype. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2001; 56(3):M146–M156. PMID:

11253156.

7. Rockwood K, Song X, MacKnight C, Bergman H, Hogan DB, McDowell I, et al. A global clinical measure of fitness and frailty in elderly people. CMAJ. 2005; 173(5):489–495. PMID:

16129869.

8. Fedarko NS. The biology of aging and frailty. Clin Geriatr Med. 2011; 27(1):27–37. PMID:

21093720.

9. Williamson JD, Supiano MA, Applegate WB, Berlowitz DR, Campbell RC, Chertow GM, et al. Intensive vs standard blood pressure control and cardiovascular disease outcomes in adults aged ≥75 years: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA. 2016; 315(24):2673–2682. PMID:

27195814.

10. Zhang W, Zhang S, Deng Y, Wu S, Ren J, Sun G, et al. Trial of intensive blood-pressure control in older patients with hypertension. N Engl J Med. 2021; 385(14):1268–1279. PMID:

34491661.

11. Whelton PK, Carey RM, Aronow WS, Casey DE Jr, Collins KJ, Dennison Himmelfarb C, et al. 2017 ACC/AHA/AAPA/ABC/ACPM/AGS/APhA/ASH/ASPC/NMA/PCNA Guideline for the Prevention, Detection, Evaluation, and Management of High Blood Pressure in Adults: A Report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Clinical Practice Guidelines. Circulation. 2018; 138(17):e484–e594. PMID:

30354654.

12. Lee HY, Shin J, Kim GH, Park S, Ihm SH, Kim HC, et al. 2018 Korean Society of Hypertension Guidelines for the management of hypertension: part II-diagnosis and treatment of hypertension. Clin Hypertens. 2019; 25(1):20. PMID:

31388453.

13. Mancia G, Kreutz R, Brunström M, Burnier M, Grassi G, Januszewicz A, et al. 2023 ESH Guidelines for the management of arterial hypertension The Task Force for the management of arterial hypertension of the European Society of Hypertension: Endorsed by the International Society of Hypertension (ISH) and the European Renal Association (ERA). J Hypertens. 2023; 41(12):1874–2071. PMID:

37345492.

14. Mahoney FI, Barthel DW. Functional evaluation: the Barthel Index. Md State Med J. 1965; 14:61–65.

15. Lawton MP, Brody EM. Assessment of older people: self-maintaining and instrumental activities of daily living. Gerontologist. 1969; 9(3):179–186. PMID:

5349366.

16. Jung HW, Yoo HJ, Park SY, Kim SW, Choi JY, Yoon SJ, et al. The Korean version of the FRAIL scale: clinical feasibility and validity of assessing the frailty status of Korean elderly. Korean J Intern Med. 2016; 31(3):594–600. PMID:

26701231.

17. Lee JY, Cho SJ, Na DL, Kim SK, Youn JH, Kwon M, et al. Brief screening for mild cognitive impairment in elderly outpatient clinic: validation of the Korean version of the Montreal Cognitive Assessment. J Geriatr Psychiatry Neurol. 2008; 21(2):104–110. PMID:

18474719.

18. Kim MH, Cho YS, Uhm WS, Kim S, Bae SC. Cross-cultural adaptation and validation of the Korean version of the EQ-5D in patients with rheumatic diseases. Qual Life Res. 2005; 14(5):1401–1406. PMID:

16047514.

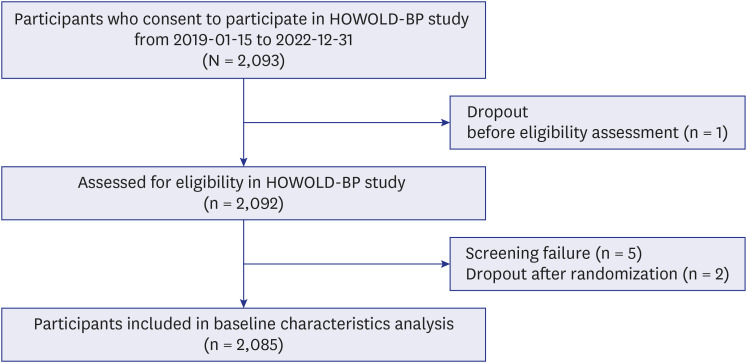

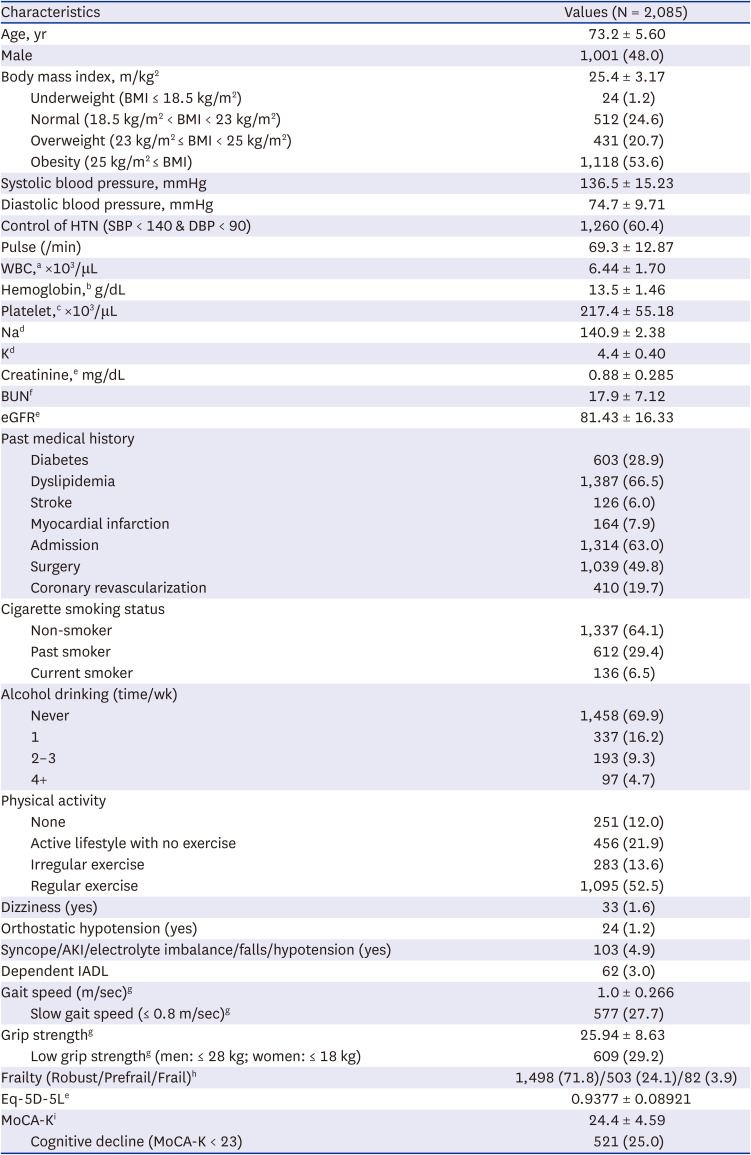

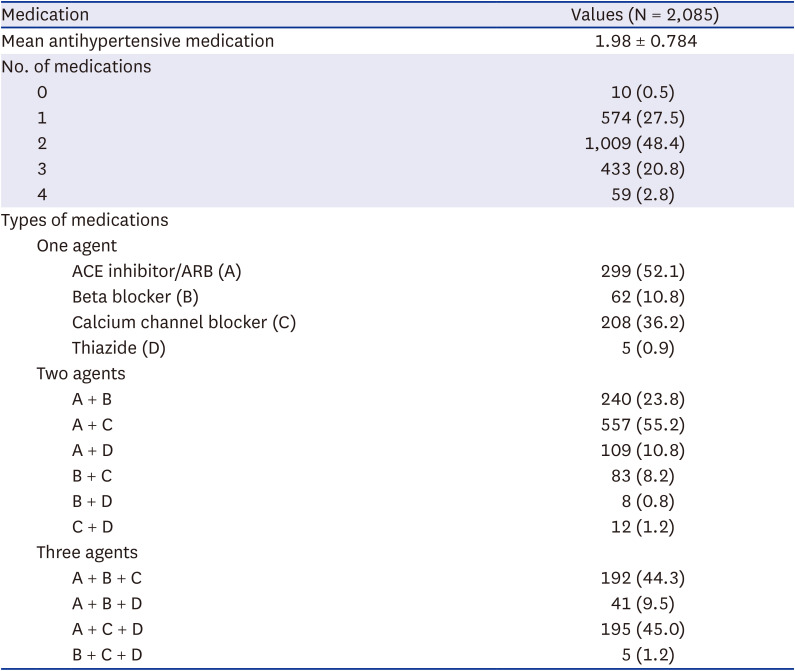

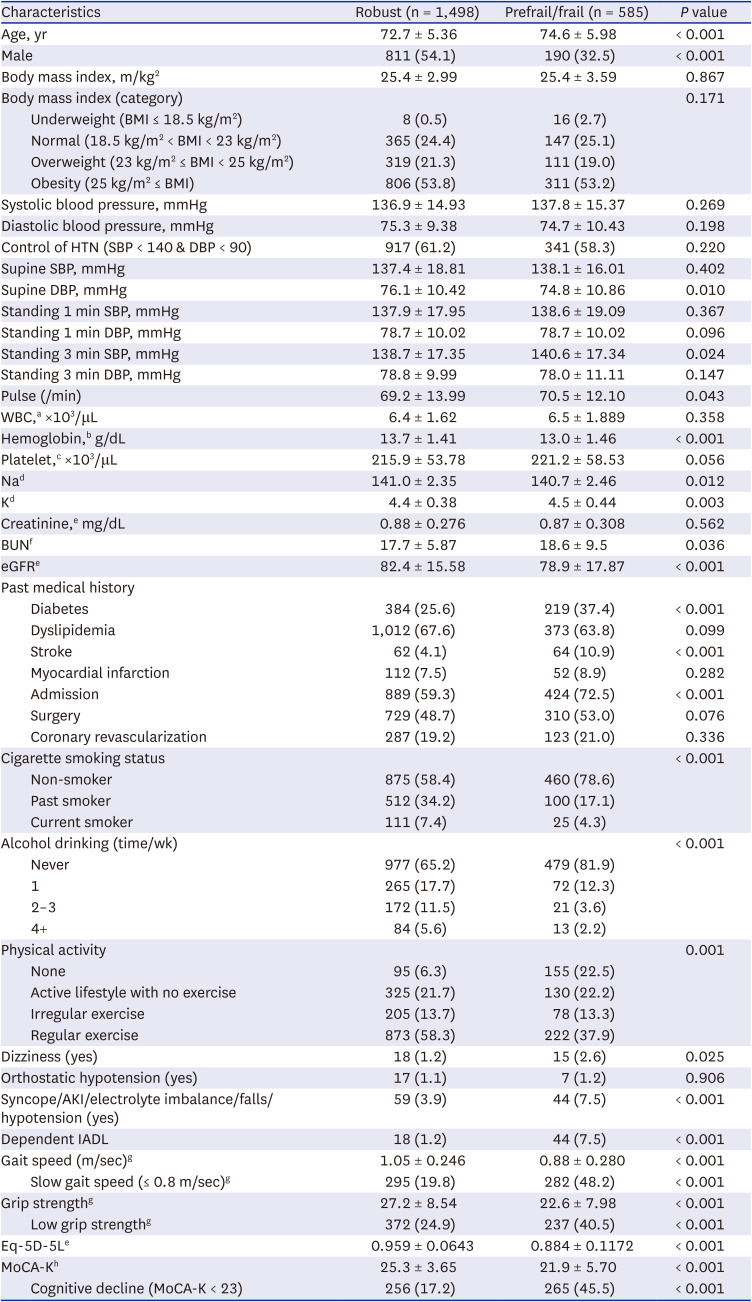

19. Lee DH, Lee JH, Kim SY, Lee HY, Choi JY, Hong Y, et al. Optimal blood pressure target in the elderly: rationale and design of the HOW to Optimize eLDerly systolic Blood Pressure (HOWOLD-BP) trial. Korean J Intern Med. 2022; 37(5):1070–1081. PMID:

35859277.

20. Zhang Y, Zhang WQ, Tang WW, Zhang WY, Liu JX, Xu RH, et al. The prevalence of obesity-related hypertension among middle-aged and older adults in China. Front Public Health. 2022; 10:865870. PMID:

36504973.

21. Whelton PK, Appel LJ, Espeland MA, Applegate WB, Ettinger WH Jr, Kostis JB, et al. Sodium reduction and weight loss in the treatment of hypertension in older persons: a randomized controlled trial of nonpharmacologic interventions in the elderly (TONE). JAMA. 1998; 279(11):839–846. PMID:

9515998.

22. Moore LL, Visioni AJ, Qureshi MM, Bradlee ML, Ellison RC, D’Agostino R. Weight loss in overweight adults and the long-term risk of hypertension: the Framingham study. Arch Intern Med. 2005; 165(11):1298–1303. PMID:

15956011.

23. Gordon EH, Peel NM, Samanta M, Theou O, Howlett SE, Hubbard RE. Sex differences in frailty: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Exp Gerontol. 2017; 89:30–40. PMID:

28043934.

PDF

PDF Citation

Citation Print

Print

XML Download

XML Download