Social media platforms are increasingly employed worldwide to disseminate publicly available information and promote the interests of diverse groups of online users.1 Students, researchers, clinicians, and patients are all exposed to a variety of such platforms to search through and satisfy their academic and societal needs. As a prime example, researchers' works are increasingly covered by online news outlets and video-sharing platforms, which translate sophisticated scientific achievements into comprehendible information, thereby popularizing science.2 The extent of social media use depends on language preferences and socioeconomic factors which are taken into account when reaching out to users in different countries and regions.3

The ease of posting and speed of disseminating information on social media enables communication between post creators and viewers in online and offline formats. Social media posts often include audio and visual materials supported with language translation tools to maximize audience engagement.4 Some of the publicly posted comments, such as those on X (formerly Twitter) and YouTube, are quantitatively weighed, contributing to aggregate alternative metrics. These metrics generated by Altmetric.com help track trends and distinguish the most influential scholarly articles, particularly in the early post-publication period.

While current health research and practice are increasingly relying on ubiquitous social media, increasing public awareness of their uses, strengths, and limitations and creating an infrastructure for posting reliable, evidence-based, and ethically sound information is increasingly important. Social media posts are often generated by public and institutional representatives who aim to engage their followers and interested users by providing feedback, commenting, and sharing information. Health-related information can be linked to anecdotal empiric experience, peer-reviewed scholarly articles, practice guidelines, and promotional medical and pharmaceutical content. Viewer discretion is often advisable since the disseminated information may contain sensitive and copyright-protected materials. Notably, public health researchers embrace social media, particularly YouTube, for study recruitments and interventions in chronic diseases, mental health, substance abuse, and infections.5 In most cases, YouTube posts on patient-sensitive and identifying information require accompanying ethics notes such as ethics approval or exemption from full ethics review.5

Online platforms like YouTube, equipped with tools for expressing viewer emotions in the form of likes and dislikes, allow quantitatively assessing subjective attitudes to published videos. However, a recent YouTube analysis in Journal of Korean Medical Science suggests that subjective metrics and number of views should not be employed as proxies of scientific evidence and ethical value.6

Skilfully designed multi-media posts with easily comprehensible content may attract the attention of diverse target groups, including students and patients who search for didactic health promotion information. The online users' social media activities may help to garner numerous views and likes. However, the most impactful societal resonance can be achieved by (re)posts with comments, or microblogging activities, boosting aggregate alternative metrics. The implications of (re)posts largely depend on individual characteristics of content generators, particularly social-media influencers with numerous followers.7

With unprecedented online activities in times of global health initiatives, the role of influencers campaigning for health promotion, physical and mental well-being, and sexual health has increased enormously, with both positive and negative impacts. For instance, a positive impact has been achieved by influencers (vloggers) campaigning for hygienic behavior in the context of COVID-19 and other infections.8 At the same time, negative consequences of vlogger activities have also been reported due to the dissemination of videos on idealistic body image and unhealthy food, causing body image dissatisfaction and anxiety among adolescents and other vulnerable subjects.9 Overall, surveys of public views have concluded that health news dissemination via social media may have mixed, positive and negative consequences, the latter due to lack of critical expert evaluations, desperate information-seeking behavior of some public representatives, and inability to distinguish scientific facts from misinformation by non-expert users.10

Over the past decade, YouTube has become a globally popular channel for sharing health-related videos in the form of educational lectures, practice instructions, research materials, and advertisements. One of the latest international surveys of YouTube users (n = 3,000) concluded that the most watched health-related videos were about exercise and bodybuilding (53%), mental health (47%), and well-being (42%).11 More than 40% of the same survey participants confirmed that watching YouTube videos on yoga, pilates, and other exercise therapies helped them to consult doctors and make decisions about improving their health. And 84.5% stressed the importance of a cautious approach to YouTube posts, while 83% preferred to watch videos by professional societies, health institutions, and other reputable organizations.11 Several analyses of YouTube videos confirmed that the lack of an evidence-based approach limits the reliability of videos and stressed the importance of posting quality videos by professional institutions.612 Overall, a systematic analysis of 22,300 YouTube videos on a variety of public health topics, dated up to 2020, qualified 40% of video items as useless or substandard.13

The scale of disseminating misleading YouTube videos was particularly alarming at the beginning of the COVID-19 pandemic and the initial stage of the related vaccine campaign. Numerous studies have pointed to the damaging effects of rumors, conspiracy theories, and baseless posts on masks, medications, and vaccines which flooded the YouTube channel and misled millions of users worldwide.1415 Notably, an analysis of 69 COVID-19 videos, viewed by more than 257 million YouTube users as of March 21, 2020, revealed that government and education sources were underrepresented (3% and 3%, respectively) and numerous videos with more than 62 million views contained non-factual information (27.5%).16 Subsequent analysis of 113 most widely viewed YouTube videos on COVID-19 confirmed that independent individual users often posted misleading information while useful posts from the World Health Organization (WHO) and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) were either scarce or unavailable.17 Likewise, an analysis of 122 most widely viewed YouTube videos on COVID-19 vaccines categorized 11% of these posts, accounting for 18 million views, as contradictory to the information provided by WHO and CDC.18 As a result, the spread of unreliable and misleading YouTube and other social-media posts had negative impacts on vaccine uptake at the height of the COVID-19 vaccination campaign.19

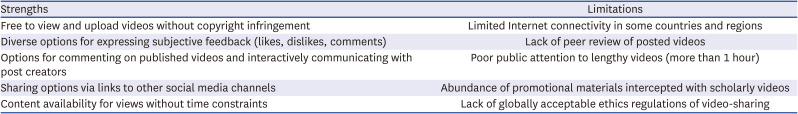

To summarise, YouTube is a readily available platform for disseminating health-related information with its strengths and limitations (Table 1). Its unique functional capacities, societal weight, and attractiveness for a wide variety of global users advantageously position this platform among other social media channels. Individual scholars and their institutions are increasingly relying on YouTube posts for sharing health information which is primarily aimed at reaching active online users. With growing social media activities, expert evaluation of the quality and reliability of disseminated videos is still an unmet need. The past decade's experience of positive and negative consequences of sharing YouTube posts necessitates upholding standards of video materials, engaging experts in critical appraisals, and guiding health consumers on how to distinguish reliable information from misleading content. Reinforcing YouTube with artificial intelligence for technical checks may further improve the evidence base and overall quality of posted health videos.

Public health post creators should consult available international ethical regulations and research reporting standards to display evidence-based materials and avoid violations of patient confidentiality and privacy. Similar to scholarly articles, displaying relevant references, disclosing conflicts of interest, and providing other ethics notes may increase the reliability of YouTube videos. In times of pandemics and other crises, government institutions and professional associations should take the lead and generate evidence-based YouTube videos to mitigate the effects of misinformation stemming from careless individual activities. The same institutions and associations should provide public guidance on how to search for reliable information and filter out misleading YouTube videos. The improved public understanding of scientific facts and health ethics can make a big difference. Concerted actions of all stakeholders and improved public perception of social media strengths and limitations may help to upgrade the standards of YouTube posts and position this social-media channel as a reliable and ethical platform for sharing health-related content.

References

1. Gasparyan AY, Yessirkepov M, Voronov AA, Koroleva AM, Kitas GD. Comprehensive approach to open access publishing: platforms and tools. J Korean Med Sci. 2019; 34(27):e184. PMID: 31293109.

2. Smith AA. YouTube your science. Nature. 2018; 556(7701):397–398. PMID: 29666498.

3. Gaur PS, Gupta L. Social media for scholarly communication in Central Asia and its neighbouring countries. J Korean Med Sci. 2021; 36(4):e36. PMID: 33496088.

4. Zimba O, Gasparyan AY. Social media platforms: a primer for researchers. Reumatologia. 2021; 59(2):68–72. PMID: 33976459.

5. Tanner JP, Takats C, Lathan HS, Kwan A, Wormer R, Romero D, et al. Approaches to research ethics in health research on YouTube: systematic review. J Med Internet Res. 2023; 25:e43060. PMID: 37792443.

6. Zhaksylyk A, Yessirkepov M, Akyol A, Kocyigit BF. YouTube as a source of information on public health ethics. J Korean Med Sci. 2024; 39(7):e61.

7. Dunn Silesky M, Sittig J, Panchal D, Bonnevie E. Digital volunteers as trusted public health communicators. Health Promot Pract. 2023; DOI: 10.1177/15248399231221158. Forthcoming.

8. Pourkarim M, Nayebzadeh S, Alavian SM, Hataminasab SH. Determination of influencers’ characteristics in the health sector. Hepat Mon. 2023; 23(1):e140317.

9. Engel E, Gell S, Heiss R, Karsay K. Social media influencers and adolescents’ health: A scoping review of the research field. Soc Sci Med. 2024; 340:116387. PMID: 38039770.

10. Gupta L, Gasparyan AY, Misra DP, Agarwal V, Zimba O, Yessirkepov M. Information and misinformation on COVID-19: a cross-sectional survey study. J Korean Med Sci. 2020; 35(27):e256. PMID: 32657090.

11. Mohamed F, Shoufan A. Users’ experience with health-related content on YouTube: an exploratory study. BMC Public Health. 2024; 24(1):86. PMID: 38172765.

12. Lee TH, Kim SE, Park KS, Shin JE, Park SY, Ryu HS, et al. Constipation Research Group of The Korean Society of Neurogastroenterology and Motility. Medical professionals’ review of YouTube videos pertaining to exercises for the constipation relief. Korean J Gastroenterol. 2018; 72(6):295–303. PMID: 30642148.

13. Osman W, Mohamed F, Elhassan M, Shoufan A. Is YouTube a reliable source of health-related information? A systematic review. BMC Med Educ. 2022; 22(1):382. PMID: 35590410.

14. Islam MS, Kamal AM, Kabir A, Southern DL, Khan SH, Hasan SMM, et al. COVID-19 vaccine rumors and conspiracy theories: The need for cognitive inoculation against misinformation to improve vaccine adherence. PLoS One. 2021; 16(5):e0251605. PMID: 33979412.

15. Sule S, DaCosta MC, DeCou E, Gilson C, Wallace K, Goff SL. Communication of COVID-19 misinformation on social media by physicians in the US. JAMA Netw Open. 2023; 6(8):e2328928. PMID: 37581886.

16. Li HO, Bailey A, Huynh D, Chan J. YouTube as a source of information on COVID-19: a pandemic of misinformation? BMJ Glob Health. 2020; 5(5):e002604.

17. D’Souza RS, D’Souza S, Strand N, Anderson A, Vogt MNP, Olatoye O. YouTube as a source of medical information on the novel coronavirus 2019 disease (COVID-19) pandemic. Glob Public Health. 2020; 15(7):935–942. PMID: 32397870.

18. Li HO, Pastukhova E, Brandts-Longtin O, Tan MG, Kirchhof MG. YouTube as a source of misinformation on COVID-19 vaccination: a systematic analysis. BMJ Glob Health. 2022; 7(3):e008334.

19. Skafle I, Nordahl-Hansen A, Quintana DS, Wynn R, Gabarron E. Misinformation about COVID-19 vaccines on social media: rapid review. J Med Internet Res. 2022; 24(8):e37367. PMID: 35816685.

Table 1

Strengths and limitations of YouTube for scholarly purposes

PDF

PDF Citation

Citation Print

Print

XML Download

XML Download