Abstract

This study measured the impact of the Decisions on Life-Sustaining Treatment Act by analyzing medical cost data from the National Health Insurance Service-National Sample Cohort. After identifying the patients who died in 2018 and 2019, the case and control groups were set using the presence of codes for managing the implementation of life-sustaining treatment with propensity score matching. Regarding medical costs, the case group had higher medical costs for all periods before death. The subdivided items of medical costs with significant differences were as follows: consultation, admission, injection, laboratory tests, imaging and radiation therapy, nursing hospital bundled payment, and special equipment. This study is the first analysis carried out to measure the impact of the Decision on Life-Sustaining Treatment Act through a cost analysis and to refute the common expectation that patients who decided to withhold or withdraw life-sustaining treatment would go through fewer unnecessary tests or treatments.

Graphical Abstract

The Act on Decisions on Life-Sustaining Treatment for Patients in Hospice and Palliative Care or at the End of Life, hereafter referred to as the Decision on Life-Sustaining Treatment Act, is a legal framework established to guarantee the best interests of patients and uphold self-determination, not to reduce medical costs.1 However, it is meaningful to measure the effectiveness of the Act based on cost analyses. Medical costs can serve as an indirect metric to assess whether patients had their best interests truly realized or their self-determination respected. The Decision on Life-Sustaining Treatment Act defines two stages: the terminal stage, which is defined by being “expected to die within a few months from the doctor in charge and one medical specialist in the relevant field in accordance with the procedures and guidelines prescribed by Ordinance of the Ministry of Health and Welfare, because there is no possibility of a fundamental recovery, and the symptoms gradually worsen despite proactive treatment,”1 and the end-of-life process, defined as “a state of imminent death, in which there is no possibility of revitalization or recovery despite treatment, and symptoms worsen rapidly.”1 Patients can withhold or withdraw life-sustaining treatment following legal procedures only after entering the end-of-life process. Any institutions making and implementing life-sustaining treatment decisions must establish an institutional ethics committee—which is realistically challenging for intermediate care hospitals—or have an outsourcing agreement concluded with a shared ethics committee.12 Such legal rigidity may hinder patients from withholding or withdrawing life-sustaining treatment, denying support to those who can benefit.2345 Also, even if a patient withholds or withdraws life-sustaining treatment as per the law, the impact of such action may be minimal to the medical care provided in the last days of their lives.6 This study aimed to measure the impact of the Decision on Life-Sustaining Treatment Act by analyzing the medical cost data from the National Health Insurance Service-National Sample Cohort (NHIS-NSC) between January 1, 2018, and December 31, 2019, based on the pilot project on medical fees from 2018 with the law coming into effect.

The NHIS-NSC is a 2.2% randomly sampled cohort from the total eligible population.7 It includes information about the patients’ insurance eligibility, medical treatment history, healthcare provider’s institution, and general health examinations. Demographic information (age, sex, residence, income, and disability), death-related information (cause and year of death), medical information (diagnosis and practice), and medical expenses before death (at 5 years, 6 months, 3 months, and 1 month) were extracted.

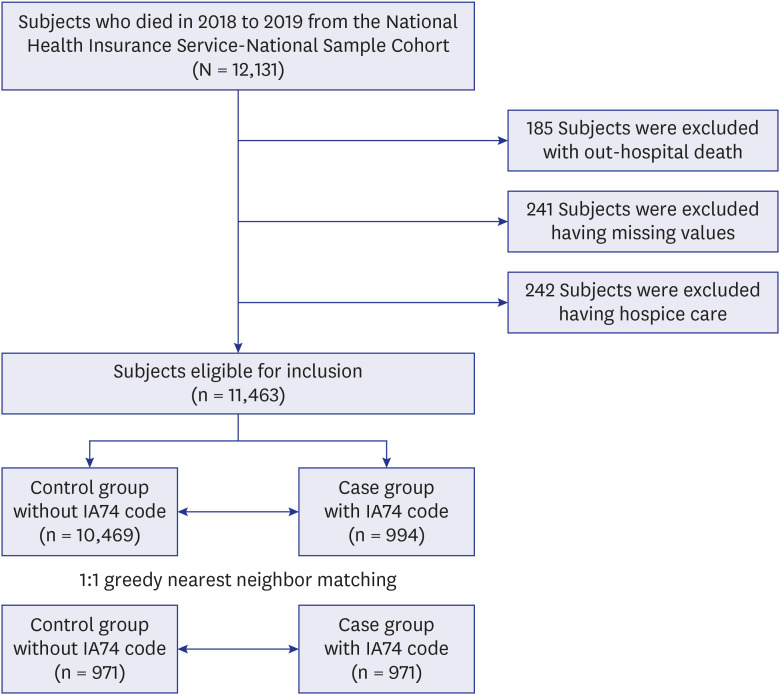

A schematic flow diagram of this nested case-control study is shown in Fig. 1. After identifying the patients who died in 2018 and 2019, we excluded those with out-of-hospital deaths, missing values, or hospice care. Subsequently, case and control groups were established using the presence of codes for managing the implementation of life-sustaining treatment, the existence of which means forgoing life-sustaining treatment according to the Decision on Life-sustaining Treatment Act (IA74). We used 1:1 propensity score matching (PSM) with multiple variables, including age, sex, residence, income, disability, cause of death, hospital stay at the time of death, intensive care unit (ICU) admission, and the Charlson comorbidity index (CCI). Residences were divided into areas according to the Korean administrative jurisdiction. Income levels were divided into quintiles and those receiving medical benefits. Disability severity was classified as none, mild, or severe. Causes of death were classified according to the Korean Standard Classification of Diseases. Hospitals at the time of death were classified into tertiary, secondary, nursing, and other hospitals according to their hospital institution codes. The CCI, the most widely used comorbidity measurement tool in claims data, was converted using the diagnosis code for hospitalization and outpatient claims for the past 1 year before death. PSM was performed using the nearest neighbor matching method, and the caliper was set to less than 0.1. The total numbers of cases and controls were 971.

Baseline characteristics are presented as means with standard deviations for continuous variables and as numbers with percentages (%) for categorical variables. Continuous variables were compared with the Student’s t-test and categorical variables with the χ2 test. Statistical analyses were performed using SAS Enterprise Guide version 8.3 (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC, USA) and R 4.3.0 (R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria). All P values less than 0.05 were considered statistically significant.

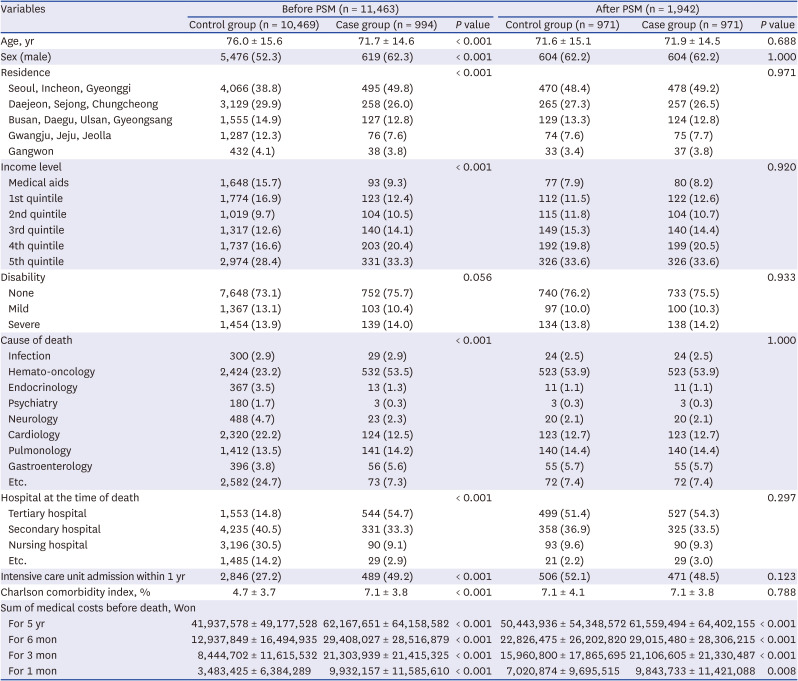

The baseline characteristics of the study population before and after PSM are shown in Table 1. Notably, the case group was homogeneously composed of those who made life-sustaining decisions, whereas the control group included people who did not meet the legal conditions for making life-sustaining decisions and those who chose not to make decisions despite meeting the legal conditions. Before PSM, the case group had younger ages, more residents in the capital, and more 5th quintile income levels. In addition, the case group had a higher proportion of haemato-oncology patients regarding causes of death and a higher proportion of tertiary hospitalizations at the time of death. The case group had more ICU admissions within 1 year and higher CCIs, indicating that they had more comorbidities. After PSM, there were no significant differences in the matching variables. Regarding medical costs, the case groups had higher medical costs for all periods, including 5 years and 6, 3, and 1 month before death, regardless of PSM.

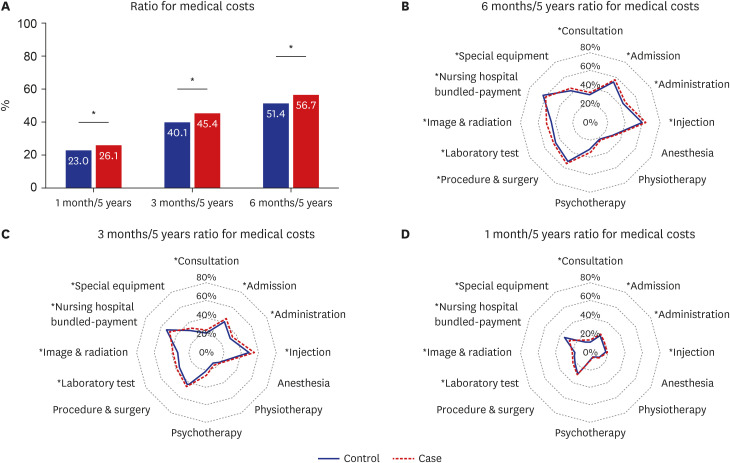

Ratios for medical costs, calculated by dividing the sum of a particular month by the sum of 5 years before death, are presented in Fig. 2. There were significant differences for medical costs, regardless of the specific period. People in the case group tended to spend more money when they were approaching death (at 6 months, 3 months, and 1 month) than those in the control group. When examining the subdivided items of medical costs, the items with statistically significant differences were as follows: consultations, admissions, injections, laboratory tests, imaging and radiation therapy, nursing hospital bundled payments, and special equipment. As death approached, all medical costs decreased, but the aforementioned items were still higher in the case group than in the control group, except for the nursing hospital bundle payments.

Before PSM, the decision to withhold or withdraw life-sustaining treatment was predominantly made within a particular population group. Before the Decision on Life-Sustaining Treatment Act was enacted, there were concerns that the law might force people with fewer resources to give up their treatment.8910 However, by dividing income into six groups and indicating the differences among the groups in life-sustaining treatment decisions, this study shows that patients who could choose to withhold or withdraw life-sustaining treatment were likely to have more financial resources. Previous studies have also displayed such partiality,6111213 indicating that, contrary to the initial concern8910 surrounding the enactment, reality showed the opposite. The case group incurred higher medical costs before death, particularly in the final stage.

The differences in medical costs may have been exaggerated for two reasons. First, differences in medical practices according to institutional differences may not have been sufficiently matched through PSM. We performed PSM according to the patient's location at the time of death. However, a lack of a trajectory before death hides the difference in different treatments usually performed at each place, for example, tertiary or nursing hospitals, where each patient spent time before their death. This difference persisted even after the PSM. The limitation of this study shows the need for a cohort that directly tracks the actual medical use of patients at the end of their lives in relation to the time point of life-sustaining treatment decisions. Second, the phenomenon that hospice patients spend relatively little may not have been reflected and the difference in cost may have been exaggerated because hospice patients who were only in the case group were excluded. However, Medical costs were consistently higher for the case group across all periods (5 years, 6 months, 3 months, and 1 month before death). Considering that three weeks is the usual period of hospice usage,14 the fact that the medical cost was high at all times suggests that this result is still significant.

As this study did not include time-series data, it should not be interpreted to mean that life-sustaining treatment decisions cause higher medical expenditures. However, this result indicates a correlation between life-sustaining treatment decisions and increased medical expenditures, which can be interpreted as having the following two negative implications. First, withholding or withdrawing life-sustaining treatments may mostly be presented as an option for resourceful patients. Resources can include not only assets in terms of income quintile and medical aid but also access to tertiary hospitals, living in large cities, better communication with physicians, and ease of decision-making based on familial emotional support. If resources are interpreted in a broader sense, the study shows that the more resources a patient has, the higher the probability of exposure to the options regarding life-sustaining treatment decisions, or the higher the probability of making those decisions. Second, patients who wanted to avoid unnecessary medical interventions in their final stage of life by withholding or withdrawing life-sustaining treatment might not have realized their intentions even with the required legal documents in place. Except for the nursing hospital bundled payments, all subdivided items of medical costs in the case group were greater during the last stage of life before death (6 months, 3 months, and 1 month to death). In particular, image diagnosis, radiation therapy, laboratory tests, and injections were performed more intensively towards the end of life, which was not quite aligned with the expectation of the patient or the patient’s family,1516 who had decided to withhold or withdraw life-sustaining treatment. The use of laboratory testing near death and temporal increment has been pointed out as problematic in a previous study.1718 Our results show that the problem of excessive testing near death is worse in the case group.

This study used data from the NHIS-NSC to understand the differences in medical expenses due to life-sustaining treatment decisions within the entire population group. Considering that a previous study11 used health screening cohort data targeting only a specific age group, this study better represents the population than the previous study. However, because fewer deaths occurred in this cohort than in the customized cohort for the dead, there is concern that the implementation status of life-sustaining care decisions and medical cost information has not been sufficiently represented. Moreover, the fact that the impact of the Decision on the Life-Sustaining Treatment Act was assessed based on a pilot project on medical fees implies that there are limitations to this study. Two limitations should be considered when drawing conclusions from this study. First, the results may be exaggerated to some extent, considering the characteristics of the pilot project, which kicks off during the initial period of implementation of the law. Preparedness for the newly implemented law may have differed depending on the size of the hospital or its location. This difference may have resulted in a somewhat exaggerated gap between the case and control groups compared to the present study. Secondly, medical cost data can only indirectly depict the actual treatments provided to patients. Although the results showed that patients who wished to avoid life-sustaining treatment had, in fact, ended up receiving more extensive treatment, it would be hasty to regard all medical interventions provided to each patient as futile based on that tendency alone. Still, as the data show that imaging, radiation therapy, laboratory tests, and injections were more intensively performed towards the end of life in the case group, it can be pointed out that these interventions are highly likely to have been unnecessary. The strength of this study is that it is the first analysis carried out to measure the impact of the Decision on the Life-Sustaining Treatment Act through a cost analysis. In addition, despite being circumstantial evidence, the study refutes the common expectation that patients who decided to withhold or withdraw life-sustaining treatment would undergo fewer unnecessary testing or treatments, serving as empirical data for policy improvement.

Notes

Author Contributions:

Conceptualization: Kim DK, Son M.

Data curation: Son M.

Formal analysis: Mun S, Son M.

Funding acquisition: Kim CJ.

Investigation: Kim DK.

Methodology: Son M.

Project administration: Kim CJ.

Resources: Kim CJ.

Software: Mun S.

Writing - original draft: Kim CJ, Son M.

Writing - review & editing: Kim DK, Mun S, Son M.

References

1. Korea Ministry of Government Legislation. Act on Hospice and Palliative Care and Decisions on Life-Sustaining Treatment for Patients at the End of Life. Updated 2023. Accessed September 12, 2023.

https://www.law.go.kr/LSW/makeMain.do

.

2. Lee E, Lee S, Baik SJ. A study on the limitations and an institutional suggestion for the life-sustaining medical care decision system. Korean J Med Law. 2022; 30(2):103–126.

3. Kim MH. The problems and the improvement plan of the Hospice/Palliative Care and Dying Patient’s Decisions on Life-Sustaining Treatment Act. Korean J Hosp Palliat Care. 2018; 21(1):1–8.

4. Jeon M. Improvement plan for the act on life-prolongation determination for well-dying. J Humanit Soc Sci 21. 2020; 11(3):1469–1481.

5. Choi JY, Jang SG, Kim CJ, Lee I. Institutional ethics committees for decisions on life-sustaining treatment in Korea: their current state and experiences with their operation. Korean J Med Ethics Educ. 2019; 22(3):209–233.

6. Won YW, Kim HJ, Kwon JH, Lee HY, Baek SK, Kim YJ, et al. Life-sustaining treatment states in Korean cancer patients after enforcement of act on decisions on life-sustaining treatment for patients at the end of life. Cancer Res Treat. 2021; 53(4):908–916. PMID: 34082495.

7. Lee J, Lee JS, Park SH, Shin SA, Kim K. Cohort profile: the National Health Insurance Service-National Sample Cohort (NHIS-NSC), South Korea. Int J Epidemiol. 2017; 46(2):e15. PMID: 26822938.

8. Kang DR. Suggestions for improving medical care decision making law through comparative legal examination. Yonsei J Med Soc Tech Law. 2018; 9(1):1–68.

9. National Assembly Library (KR). Health and Welfare Committee 337th meeting minutes No. 12. Updated 2015. Accessed September 12, 2023.

https://dataset.nanet.go.kr/

.

10. Jung ST. A Study on the Improvement and Efficient Utilization of the Life-Sustaining Treatment Decision System - Focused on the Law About Hospice Palliative Care and the Life-Sustaining Treatment Decision System for Patients in the Dying Process -. Daegu, Korea: Daegu Haany University;2016.

11. Kim JC, Kim D, Mun S, Son M. Current status of implementation of the decision to forgo life-sustaining treatment through big data of the National Health Insurance Service. Bio Ethics Policy. 2023; 7(1):1–24.

12. Chung S, Seon JY, Oh IH, Park SY. The status of the enforcement of pilot projects on medical fees for decision making involving life-sustaining treatment. Bio Ethics Policy. 2022; 6(1):51–68.

13. Park SY, Lee B, Seon JY, Oh IH. A national study of life-sustaining treatments in South Korea: what factors affect decision-making? Cancer Res Treat. 2021; 53(2):593–600. PMID: 33227190.

14. Ministry of Health and Welfare (KR). 2022 National Hospice and Palliative Care Annual Report. Goyang, Korea: National Hospice Center;2022.

15. Yun YH, Rhee YS, Nam SY, Chae YM, Heo DS, Lee SW, et al. Public attitudes toward dying with dignity and hospice, palliative care. Korean J Hosp Palliat Care. 2004; 7(1):14–28.

16. Chung KH, Kim KR, Seo JH, Yoo JE, Lee SH, Kim HJ. Ensuring Dignity in Old Age With Improved Quality of Death. Sejong, Korea: Korea Institute for Health and Social Affairs;2018.

17. Kim HA, Cho M, Son DS. Temporal change in the use of laboratory and imaging tests in one week before death, 2006-2015. J Korean Med Sci. 2023; 38(12):e98. PMID: 36974403.

18. Kang SH, Seo YI, Lee MH, Kim HA. Diagnostic value of anti-nuclear antibodies: results from Korean university-affiliated hospitals. J Korean Med Sci. 2022; 37(19):e159. PMID: 35578590.

Fig. 1

The flow of study population.

IA74 codes indicate management for the implementation of life-sustaining treatment.

Fig. 2

Ratio for medical costs in specific periods between control and case groups.

*P value < 0.05, compared between the control and case groups.

Table 1

Baseline characteristics of study population before and after PSM

PDF

PDF Citation

Citation Print

Print

XML Download

XML Download