Implementation of global mass vaccination campaign against coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) has led more than 70% of the world population to receive at least 1 dose of COVID-19 vaccine.

1 Initial vaccine rollout was prioritized for the elderly and healthcare providers, followed by adults and adolescents. The emergency use authorization by the US Food and Drug Administration expanded in the late 2021 to cover children aged between 5 and 11 years based on the finding on effectiveness in preventing COVID-19 comparable to that reported in general population.

2

Targeting individuals with vaccine hesitancy is a key to achieving high vaccine coverage against COVID-19. An international survey of 23 countries found individuals’ acceptance rate of 79.1% toward primary series of COVID-19 vaccine, but also observed increasing trend of hesitancy towards a booster dose.

3 Similarly, our previous study on COVID-19 booster hesitancy showed 48.8% of adults who completed the primary series in South Korea were hesitant about receiving an additional dose mainly due to concerns on safety and doubts on efficacy of COVID-19 vaccination.

45 This growing hesitancy in the adult population is likely to impact COVID-19 vaccine uptake in children. In South Korea, COVID-19 vaccination for children aged between 5 and 11 years began in May 2022, yet official reports indicate slow uptake with only 1.1% completing the primary series as of May 31

st, 2023. As parents will decide COVID-19 vaccination in children, this study aimed to describe parental and child characteristics associated with hesitancy toward COVID-19 vaccination for children.

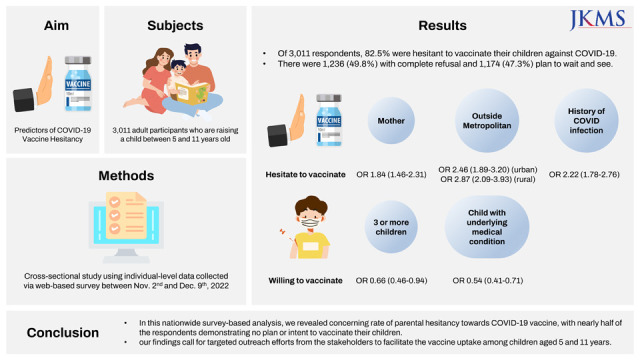

We conducted a cross-sectional study using individual-level data collected via the Gallup Panel online survey between November 2nd and December 9th, 2022. Eligible survey participants were adults who have a child between 5 and 11 years old residing in South Korea. For those who had 2 or more children within this age group, they were asked to choose one with the earlier date and month of birth when completing the survey. Gallup Korea, an affiliation of Gallup International, distributed the survey via e-mail to the panels stratified by child’s age groups (i.e., 5–7, 8–9 and 10–11 years), sex and regions using a proportional allocation method. Upon completion of survey, respondents were weighted by age, sex and regions to be representative of the South Korean population.

In order to estimate the rate of parental hesitancy towards COVID-19 vaccination for children, survey participants were asked for willingness to vaccinate their children against COVID-19 with the following response options: 1) “already completed primary series of COVID-19 vaccination,” 2) “received the first and plan to receive second dose in a timely manner,” 3) “plan to receive the first dose in a timely manner,” 4) “received the first dose but refuse second dose,” 5) “wait and see” or (6) “no plan for vaccination.” Acceptant group in this study included those who responded with options 1), 2) or 3), and hesitant group with options 4), 5) or 6). We compared the characteristics between the two groups to identify potential predictors of child COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy. The following characteristics of the respondents were assessed: age, sex, region, education level, number of children in household, presence of underlying medical condition(s), history of COVID-19 diagnosis, COVID-19 vaccination status, history of serious adverse event (AE) following COVID-19 vaccination, and individual’s perception on the safety and effectiveness of COVID-19 vaccination. Additionally, we collected data on the characteristics of the respondents’ children including their sex, age, underlying medical condition(s), history and time (i.e., month and year) of COVID-19 diagnosis, and influenza vaccination in the past 3 years.

The overall characteristics of the respondents were reported using means (standard deviation) for continuous and frequencies (percentage) for categorical variables. Multivariate logistic regression model was used to estimate the weighted odds ratios (ORs) and corresponding 95% confidence intervals (CIs) of each factor in hesitant vs. acceptant groups. All statistical analyses were performed using SAS version 9.4 (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC, USA) and Microsoft Excel (Microsoft Corp., Redmond, WA, USA).

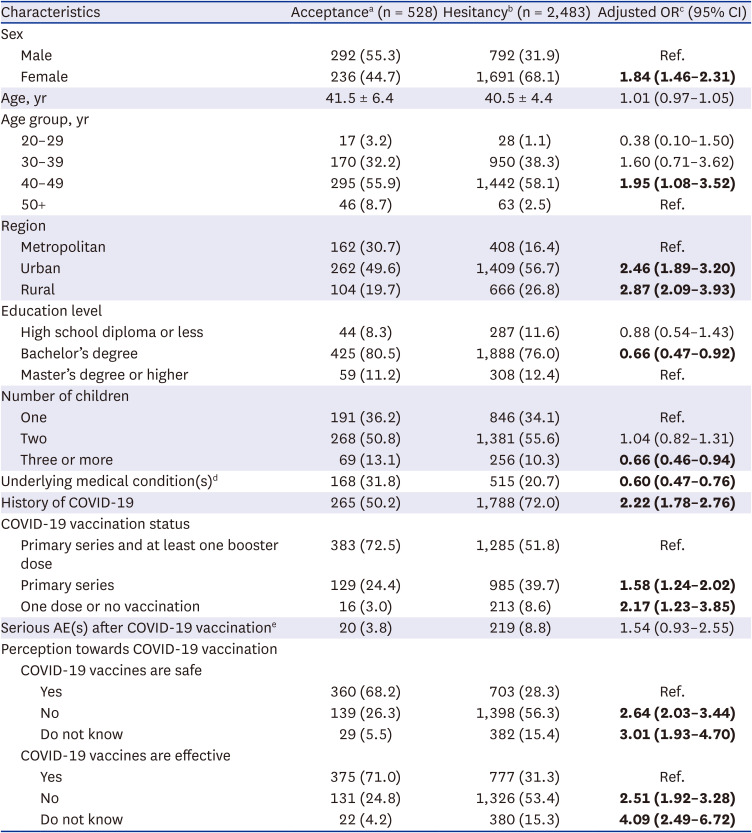

A total of 28,549 invitations were sent, 4,516 (15.8%) participants attempted and 3,011 (66.7%) completed the survey. Of the 3,011 respondents, 82.5% were hesitant to vaccinate their children against COVID-19 (

Table 1). Among them, 1,236 (49.8%) completely refused and 1,174 (47.3%) plan to wait and see. Compared with acceptant group, being women (OR, 1.84; 95% CI, 1.46–2.31), aged between 40–49 vs. 50+ years (1.95 [1.08–3.52]), residing outside of metropolitan area (urban: 2.46 [1.89–3.20]; rural: 2.87 [2.09–3.93]), prior COVID-19 diagnosis (2.22 [1.78–2.76]), completing only primary series (1.58 [1.24–2.02]) or no COVID-19 vaccination (2.17 [1.23–3.85]) were parental characteristics associated with hesitancy towards COVID-19 vaccination for children. Moreover, the hesitancy was higher among those who do not believe or indifferent towards safety (ORs 2.64 [2.03–3.44] and 3.01 [1.93–4.70], respectively) and effectiveness (2.51 [1.92–3.28] and 4.09 [2.49–6.72], respectively) of COVID-19 vaccination. Conversely, parents were less likely to be hesitant if they had underlying medical conditions (0.60 [0.47–0.76]), raising three or more children (0.66 [0.46–0.94]) or with bachelor’s vs. master’s or higher degree (OR 0.66 [0.47–0.92]).

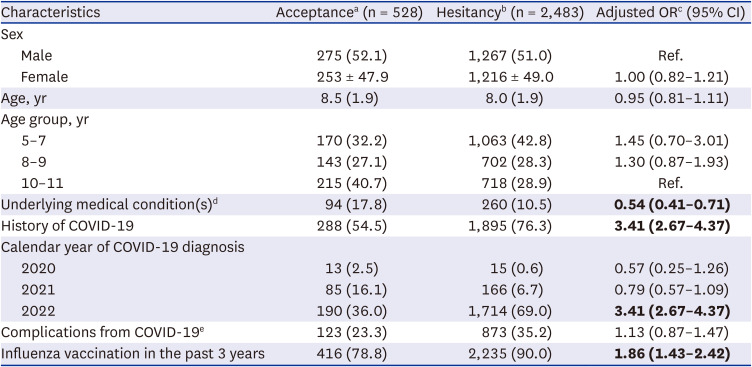

In regard to child characteristics, parents were hesitant if their children had been diagnosed with COVID-19 recently (i.e., in 2022: OR 3.41 [2.67–4.37]) or received influenza vaccination in the past 3 years (1.86 [1.43–2.42]), whereas less likely to be hesitant if their children had underlying medical conditions (0.54 [0.41–0.71]) (

Table 2).

In this nationwide survey-based analysis, we revealed concerning rate of parental hesitancy towards COVID-19 vaccine, with nearly half of the respondents demonstrating no plan or intent to vaccinate their children. Amongst the assessed predictors, we found respondents’ disbelief or indifference on COVID-19 vaccine effectiveness and recent COVID-19 diagnosis of their children as the major barriers against COVID-19 vaccine uptake, whereas presence of underlying medical conditions in parents or children were likely to improve the uptake.

Our observed parental hesitancy rate is much higher than those reported previously. Recent meta-analysis on parental willingness towards COVID-19 vaccination for children aged < 18 years indicate that 22.9% were completely against vaccination and 25.8% were unsure.

6 While this was pooled from studies conducted up to December 2021, the hesitancy rate indeed can fluctuate across different time points and COVID-19 waves. For instance, COVID-19 vaccine acceptance rate among survey respondents in Hong Kong decreased from 44.2% in the first local epidemic wave to 34.8% in the third wave.

7 Alternatively, the acceptance may also improve upon introduction of the vaccine as observed from the surveys of healthcare workers in the United States showing an increase in the intention to receive COVID-19 vaccine from 36% in November 2020 to 85% in March 2021 following the emergency use authorization.

89 This was also notable in our study showing improved acceptance rate of 17.5%, compared with 6.5% reported from a survey of parents in South Korea administered 2 months before the initiation of COVID-19 vaccination for children aged 5 to 11 years.

10 Nonetheless, our estimated prevalence of parental hesitancy on COVID-19 vaccination for children in South Korea is substantially higher than those reported previously,

6 underscoring a need for target intervention to facilitate vaccine uptake in children.

Expectedly, we observed high prevalence of the parental hesitancy among those who responded that they do not believe the effectiveness or safety of COVID-19 vaccine. It has been shown that people adhere to immunization campaigns when they are presented with credible information.

11 In the case of COVID-19 vaccination, its credibility had been threatened by the growing numbers of negative information, often unvalidated, disseminated through social media platform.

12 Moreover, routine childhood immunization rate in South Korea has remained stable during the COVID-19 pandemic,

13 which further suggests the observed hesitancy was specific to COVID-19 vaccination and highlights a need for dissemination of positive information from credible sources including health authorities and healthcare providers.

While it would be expected the predictors of parental hesitancy to be generally in line with those in general adults, some were unique to the child COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy. Factors such as being a woman, younger age, low education level and history of AE following COVID-19 vaccine were known predictors of COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy among general population.

41415 In the present study, apart from being a woman, these predictors were not key determinant of the parental hesitancy, and rather parents with lower education level were less likely to be hesitant toward vaccinating their children. More importantly, it was concerning to note history of COVID-19 diagnosis as one of the strongest predictors of child COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy, and this may be attributed to individual’s misbelief that a natural immunity gained from single COVID-19 case confers protection against re-infection. However, a recent meta-analysis has shown that protection against re-infection by the Omicron BA.1 variant was estimated at only 36.1% by 40 weeks after last COVID-19 episode.

16 As 87.2% of respondents’ children in this study were diagnosed with COVID-19 in 2022, when detection rate of the omicron variant was over 90% in South Korea,

17 proactive measures are in need to avoid the foreseeable future burden of COVID-19 by promoting vaccine uptake in this pediatric population. It was also interesting to note prior influenza vaccination as one of the predictors of parental hesitancy. In our previous study, Korean adults were generally less hesitant to receive COVID-19 booster dose if they had received influenza vaccination in the past years.

4 While we assert that children’s past experience on influenza vaccination may have negatively impacted their perception on future vaccination, additional research is needed to confirm this potential association observed in our present study.

Several limitations should be considered in interpreting this study’s findings. First, true prevalence of the parental hesitancy may be underestimated from social desirability bias, an inherent limitation of questionnaire-based survey. Second, our findings are based on a single time point (i.e., December 2022), and whether the observed association would remain same in the present time remains unclear given the complex dynamics of COVID-19 pandemic. Lastly, the generalizability of our findings outside the South Korean population may be limited given the differences in COVID-19 vaccination access and compliance with government policies.

In conclusion, our findings highlight the high prevalence of parental hesitancy towards COVID-19 vaccination for children and call for targeted outreach efforts from the stakeholders to facilitate the vaccine uptake among children aged 5 and 11 years.

Ethic Statement

This study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of Sungkyunkwan University (SKKU 2022-09-022), and all respondents consented to participate in the survey.

PDF

PDF Citation

Citation Print

Print

XML Download

XML Download