This article has been

cited by other articles in ScienceCentral.

Abstract

Background

The present study examined changes in the working hours of Korean workers from 2010 to 2020 according to employment status and industrial sector.

Methods

This was a secondary analysis of data from the third (2010), fourth (2014), fifth (2017) and sixth (2020) Korean Working Conditions Surveys, which were conducted by the Korea Occupational Safety and Health Agency.

Results

During the past 10 years, workers classified as employees, self-employed, or employers experienced clear declines in average weekly working hours and in the percentages of individuals who worked more than 48 hours per week. During 2020, the largest proportion of employees (52.8%) had 40-hour work weeks, whereas the largest proportions of self-employed individuals (26.8%) and employers (25.1%) had very long work weeks (≥ 60 h/week). Also during 2020, individuals who were self-employed or employers in the sectors of ‘Accommodation and food service’ had the longest weekly work hours, whereas employees in the sector of ‘Transportation’ had the longest weekly work hours. All three groups (employees, self-employed, and employers) in all 21 industrial sectors experienced declines in average weekly working hours from 2017 to 2020.

Conclusion

From 2010 to 2020, employees, self-employed individuals, and employers experienced clear declines in average weekly working hours, and in the percentages of individuals with long weekly working hours. However, there were also differences in the weekly working hours of those who had different employment status and who worked in different industrial sectors. The implementation of the 40-hour work-week and the 52-hour maximum work-week in Korea reduced excessive work hours by individuals who had different employment status and who worked in different industrial sectors, and probably improved worker quality-of-life. We recommend extension of these regulations to workplaces with fewer than 5 employees.

Keywords: Working Hour, Work Week, Long, Employment Status

INTRODUCTION

Employed individuals in Korea typically work more hours than those in other countries of the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD).

1 This can be concerning because long working hours can adversely affect worker safety and health.

234 We previously examined long working hours in Korea using results from the 2006 and 2014 Korean Working Conditions Survey (KWCS). For this 8-year period, the average weekly working hours in all groups was less during 2014 than during previous years; however, self-employed individuals and employers in specific service sectors worked more than 60 hours per week during 2014. Individuals who were self-employed or employers worked longer hours than employees, because employees are protected by the Labor Standards Act of Korea, and this difference was particularly notable in the ‘Accommodations and food service’ sector.

56 In 2004, Korea passed legislation that established the 40-hour work week as a standard in an effort to improve quality-of-life and increase business competitiveness. This requirement was introduced in stages, and was completely implemented for all workplaces with 5 or more employees in 2011.

7 Furthermore, in 2018, Korea passed legislation stating that work during any particular week should not exceed 52 hours and during any particular day should not exceed 12 hours. This requirement was introduced in stages; companies with 300 employees or more and public corporations had to be compliant by July 1, 2018

8; companies with 50 to 299 employees by January 1, 2020; and companies with 5 to 49 employees by July 1, 2021.

The present study compared the working hours of Korean workers during October 2020 and April 2021 (when the new regulations were not yet extended to all workplaces) with previous data from 2010 and 2014. The present study has two hypotheses. First, based on the maximum 52-hour work week regulation (currently applied to workplaces with 50 employees or more) and the standard 40-hour work week regulation (completely implemented in 2011), we hypothesized there was a steady decrease of weekly working hours for Korean workers overall since 2010. Second, we hypothesized that self-employed individuals continued to work long hours because they are not subject to the new Labor Standards Act.

METHODS

This study was a secondary analysis of data from the third (2010), fourth (2014), and fifth (2017) KWCS that was conducted by the Korea Occupational Safety and Health Agency.

910 Data were also from the sixth KWCS, which was postponed until October 2020 and April 2021 due to coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic.

11 The survey population was a representative sample of workers who were at least 15 years-old, the legal minimum working age in Korea. Individuals were included if they worked for pay or profit for at least 1 hour during the week preceding the interview. Thus, individuals who were retired, unemployed, homemakers, or students were excluded. Individuals were classified as employees if they worked for pay, as employers if they worked for profit and used paid employees, and as self-employed if they worked for themselves and did not use paid employees.

The basic study design was a multistage random sampling in the enumeration districts used for the 2010 and 2021 population and housing censuses. Approximately 50,000 face-to-face interviews were conducted as planned. Depending on the survey year, there were a total of 47,446, 47,129, 47,742, and 47,111 research subjects in 2010, 2014, 2017, and 2020, respectively. The number of self-employed individuals declined steadily from 2010 to 2020 (8,436, 7,945, 7,677, and 7,540, respectively). The number of employers also declined steadily from 2010 to 2020 (3,106, 3,002, 2,993, and 2,373, respectively). However, the number of employees increased steadily from 2010 to 2020 (35,903, 36,183, 37,073, and 37,198, respectively). The survey data were weighted with reference to the economically active population, in that the sample distributions by region, locality, sex, age, economic activity, and occupation were identical to those of the overall economically active population at the time of the survey. The questionnaire collected information about hours of work, physical risk factors at work, work organization, and other related data. The methodology and questionnaire were almost identical to those of the European Working Conditions Survey.

12

Ethics statement

A participant provided written informed consent. This research was approved by the Institutional Review Board (IRB) of Ulsan University Hospital (IRB File Nos. 2020-06-007, UUH 2022-07-034).

RESULTS

Changes in average weekly working hours from 2010 to 2020

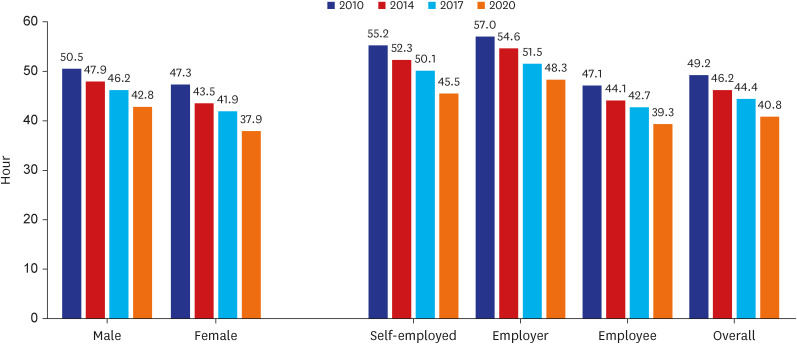

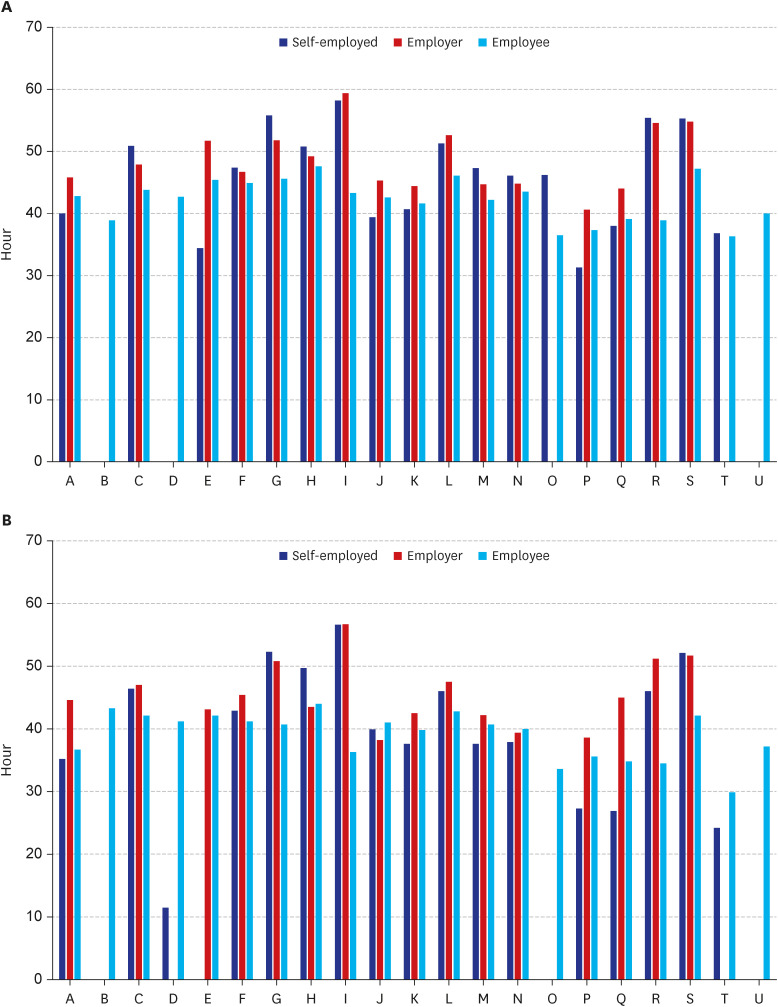

The average weekly working hours of employed Korean workers overall declined steadily from 2010 to 2020 (2010: 47.1 hours; 2014: 44.1 hours, 2017: 42.7 hours, 2020: 39.3 hours;

Fig. 1). In particular, during 2020 self-employed individuals worked an average of 45.5 h/week, employers worked an average of 48.3 h/week, and employees worked an average of 39.3 h/week. Also during 2020, men worked an average of 42.8 h/week and women worked an average of 37.9 h/week. Thus, males and females, and all three groups (self-employed, employers, and employees) worked fewer hours per week from 2010 to 2020.

Fig. 1

Average weekly working hours from 2010 to 2020 according to sex, employment status, and overall.

Changes in long working hours from 2010 to 2020

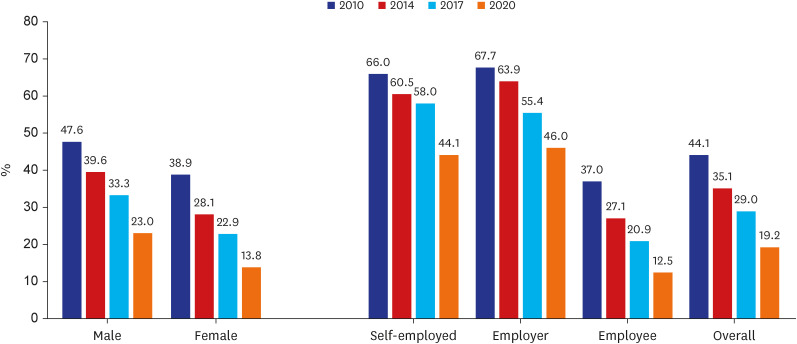

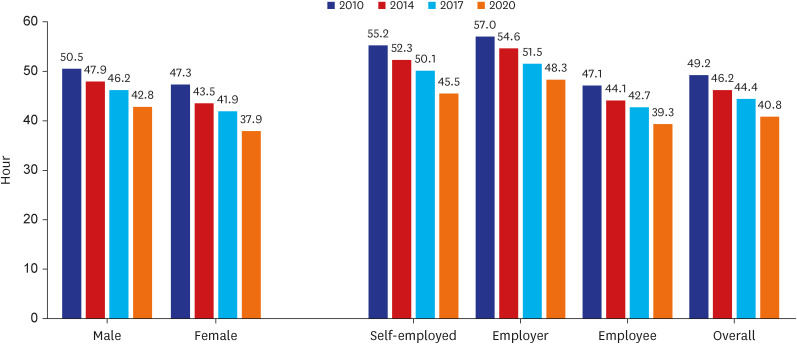

In 2020, 19.2% of all Korean workers had an average work week of more than 48 h, defined as “long working hours” by the International Labor Organization (

Fig. 2). The percentage of employees with long working hours decreased from 37.0% in 2010 to 12.5% in 2020; the percentage of self-employed individuals with long working hours decreased from 66.0% in 2010 to 44.1% in 2020; and the percentages of employers with long working hours decreased from 67.7% in 2010 to 46.0% in 2020. In 2020, 23.0% of men and 13.8% of women had long working hours. Thus, males and females, and all three groups (self-employed, employers, and employees) experienced clear declines in the percentages of individuals with long working hours from 2010 to 2020.

Fig. 2

Percentage of individuals who worked more than 48 h/week from 2010 to 2020 according to sex, employment status, and overall.

Weekly working hours by employment status

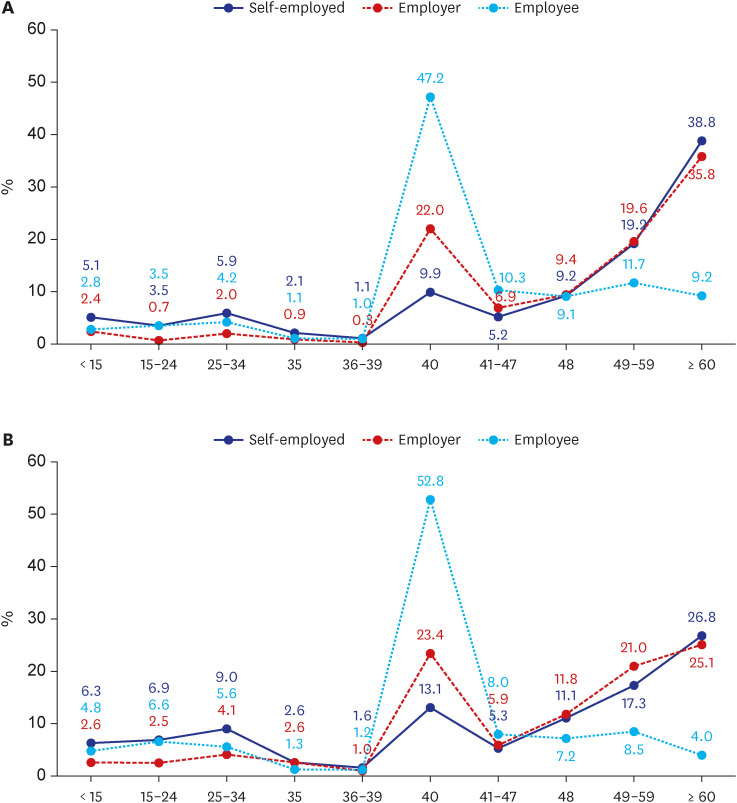

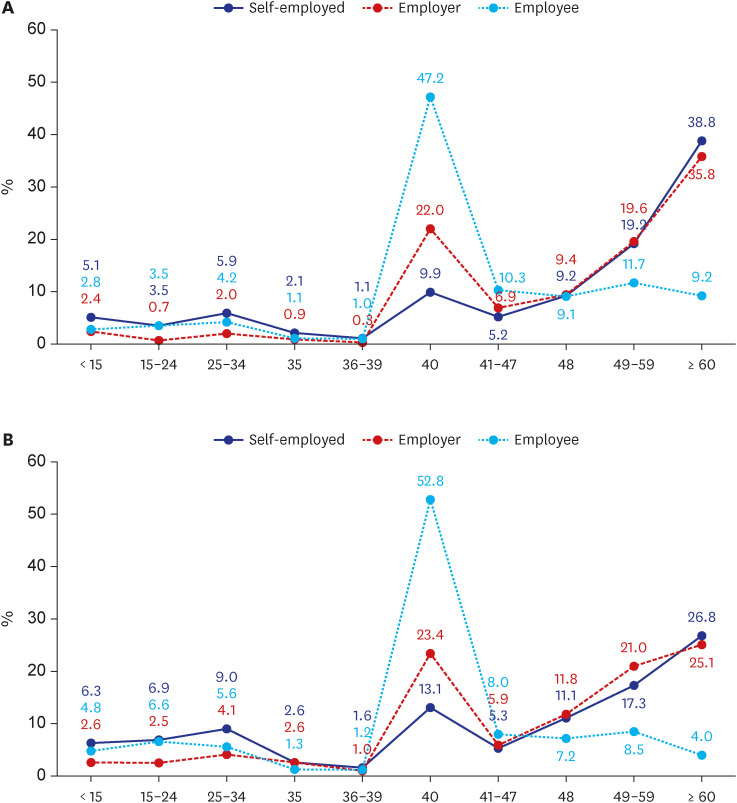

We also compared weekly working hours in 2017 and 2020, using the 10 working-hour bands recommended by the International Labor Organization for type of employment (

Fig. 3).

13 During 2020, most employees (52.8%) had 40-hour work weeks, whereas 26.8% of the self-employed individuals and 25.1% of employers had “very long working hours”, defined as at least 60 h/week. Notably, all three groups experienced declines in the percentages of individuals with very long working hours from 2017 to 2020 (self-employed: 38.8% to 26.8%; employers: 35.8% to 25.1%; employees: 9.2% to 4.0%).

Fig. 3

Frequency distribution of weekly working hours for individuals who had different employment status during (A) 2017 and (B) 2020.

Weekly working hours by industrial sector

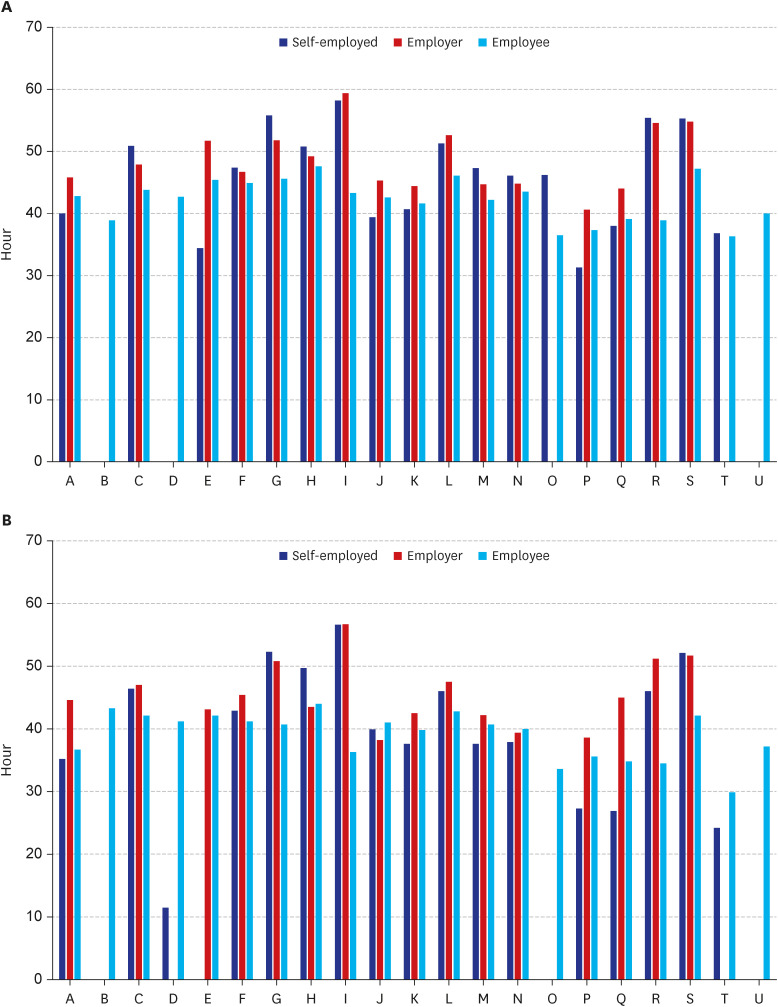

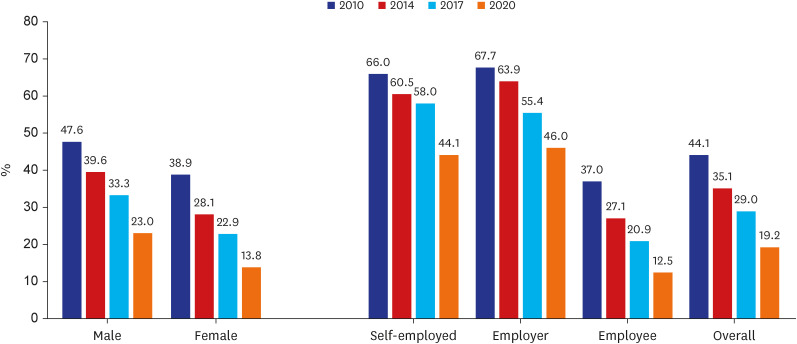

We then analyzed average weekly working hours for 21 different industrial sectors (

Fig. 4). In 2020, for individuals who were self-employed or employers, those in the sector of ‘Accommodation and food service’ had the longest work weeks; for individuals who were employees, those in the sector of ‘Transportation’ had the longest work weeks. Furthermore, individuals who were self-employed or employers in the sectors of ‘Wholesale and retail trade’ or ‘Membership organization, repair, and personal services’ worked longer hours, whereas employees in the sector of ‘Mining and quarrying’ or ‘Real estate activities, renting, and leasing’ worked longer hours. All three groups (self-employed, employers, and employees) in all 21 industrial sectors had declines in weekly working hours from 2017 to 2020.

Fig. 4

Average weekly working hours in 21 different industrial sectors for individuals who had different employment status during (A) 2017 and (B) 2020.

Industrial legends: A, Agriculture, forestry, and fishing; B, Mining and quarrying; C, Manufacturing; D, Electricity, gas, and water supply; E, Waste management, materials recovery; F, Construction; G, Wholesale and retail trade; H, Transportation; I, Accommodation and food services; J, Information and communications; K, Financial and insurance activities; L, Real estate activities, renting, leasing; M, Professional, scientific, and technical activities; N, Business facilities management and business support services; O, Public administration and defense, social security; P, Education; Q, Health and social work activities; R, Arts, sports, and recreation-related services; S, Membership organization, repair, and personal services; T, Household employer activities U, International and foreign organizations.

DISCUSSION

The effect of exposure to long working hours on stroke was recently reported with a systematic review and meta-analysis from the World Health Organization (WHO)/International Labour Organization (ILO) Joint Estimates of the Work-related Burden of Disease and Injury. Evidence on exposure to working ≥ 55 h/week was judged as “sufficient evidence of harmfulness” for ischemic heart disease incidence and mortality, and stroke incidence.

1415 Thus, reducing working hours will not only improve the quality of life but also help prevent cardiovascular disease in Korean workers.

When it became clear that Koreans worked longer hours than those in other OECD countries, the Korean government implemented a policy that aimed to reduce working hours. Thus, in 2004, the Korean government legislated a standard 40-h work week for workplaces with 5 or more employees, and introduced regulations in stages according to the size of workplace. These policies were completely implemented in July 2011. Also, on July 1, 2021, the maximum 52-h work-week regulation was applied to workplaces with 5 to 49 employees. Thus, we expected a significant decrease in the weekly working hours of Korean employees from 2010 to 2020.

Employees in Korea experienced a clear decline in average weekly working hours, from 47.1 h/week in 2010 to 39.3 h/week in 2020. The percentage of employees who worked an average of more than 48 h/week decreased from 37.0% in 2010 to 12.5% in 2020 (

Fig. 2), and the percentage of employees who worked 40 h/week (legal working time) increased from 47.2% in 2017 to 52.8% in 2020. Moreover, in 2014, employees in all sectors worked an average of 50 h/week, and the proportion of employees working more than 40 h/week remained high in 2020 (27.7%). This may be because the standard 40-h work-week regulation does not apply to workplaces with fewer than 5 employees, and these workplaces account for approximately 13% among all employees. The Labor Standard Act permits more than 12 hours of overtime work per week when there is an agreement between labor and management in certain occupations such as transportation and health care. Thus, employees with the occupation of transportation tend to work longer hours, which was also shown in the industrial sector of transportation (

Fig. 4).

Despite the decreasing trend, the yearly working hours in Korea continue to exceed 1,900 hours. Using OECD figures, 1,915 yearly working hours in Korea are still longer compared to those in other industrialized countries such as France (1,490), Germany (1,349), the United States (1,791), and Japan (1,607).

16

Notably, the weekly working hours of the self-employed, who are not subject to the Labor Standards Act, also fell sharply from an average of 55.2 hours in 2010 to 45.5 hours in 2020. The proportion of the self-employed who worked more than 48 hours also decreased from 66.0% in 2010 to 44.1% in 2020. These recent steep decreases in this group may be because authorities recently restricted business hours due to the COVID-19 pandemic. Our results indicated that average weekly working hours for the self-employed did not exceed 60 hours in any of the 21 industrial sectors in 2017 or in 2020, although previous research reported the self-employed had more than 60 average weekly working hours during 2010 in several sectors, such as ‘Accommodation and food service’ and ‘Wholesale and retail trade’. Thus, the decline in legal working hours of employees apparently drove a similar reduction in the working hours of the self-employed. Further study is necessary to determine if the reductions in working hours identified here are attributable to factors other than the new legislation.

The self-employed and employers tended to work many more hours than employees, because employees are protected by the Labor Standards Act. Although from 2017 to 2020, the proportion those who work very long hours (60 h/week or more) decreased steadily for the self-employed (38.8% to 26.8%) and for employers (35.8% to 25.1%), these percentages were still higher than those for employees (9.2% in 2017 and 4.0% in 2020). This difference was particularly notable for certain service sectors, such as ‘Accommodation and food services’, although the average weekly working hours decreased over time for workers in all 21 industrial sectors. Therefore, we recommend future studies compare average working hours in workers overall, as well as differences in working hours according to employment status and industrial sector.

In summary, the KWCS results from 2010 to 2020 demonstrated that the weekly working hours for Korean workers overall decreased steadily from 2010 to 2020, although there were differences according to employment status and industrial sector. Current evidence suggests that the 40-hour work-week may have improved the quality-of-life of Korean workers. Thus, the application of the 40-hour standard work-week and a 52-hour maximum work-week should be extended to workplaces with fewer than 5 employees, which are not currently subject to these regulations.

However, there were also increases in the numbers of workers with different classifications during the study period, such as ‘platform workers’, who are not subject to the current regulations.

17 We therefore also suggest analysis of the working hours of these new types of workers and the working hours of individuals who have two or more jobs.

PDF

PDF Citation

Citation Print

Print

XML Download

XML Download