This article has been

cited by other articles in ScienceCentral.

PRESENTATION OF CASE 7

Dr. Moon Kyung Jung: An 18-year-old man was admitted to this hospital because of dyspnea, cough and myalgia. Because there was no clinical improvement with the treatment of ceftriaxone and clarithromycin at another hospital for 2 days, he had visited this hospital. He started smoking two weeks ago and had been diagnosed with atopic dermatitis and asthma previously, but he did not take any medications. On physical examination, the blood pressure was 128/68 mmHg, the heart rate 83 beats per minute, the respiratory rate 20 breaths per minute, the temperature was 37.4°C and an oxygen saturation of 98% while he was breathing with nasal cannula at 2 L/min flow rate. Coarse crackles were heard at the entire lung field and the heart sounds were regular without murmur. Eosinophils were elevated (5.9%) in complete blood count. There was no specific findings in blood chemistry except elevated inflammatory markers such as CRP (15.11 mg/dL) and procalcitonin (2.98 ng/mL). Chest X-ray showed hazy opacities in both lungs. In the arterial blood gas panel, pH was 7.350, pCO2 was 43.3 mmHg, pO2 was 102 mmHg and HCO3 was 22.9 mmol per liter which was measured when oxygen was supplied by 2 L/min nasal cannula. PaO2/FiO2 ratio was 364.3 and alveolar-arterial gradient was 43.5 mmHg.

DIAGNOSTIC TESTS

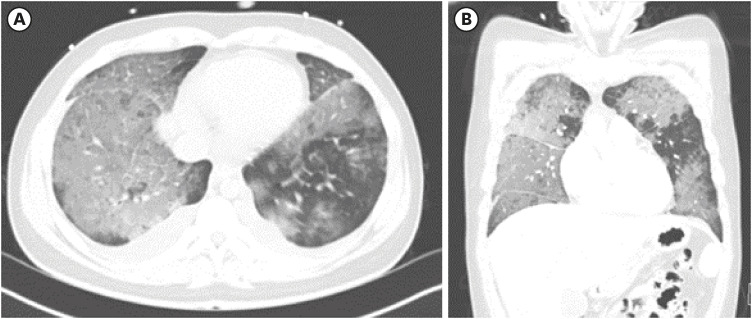

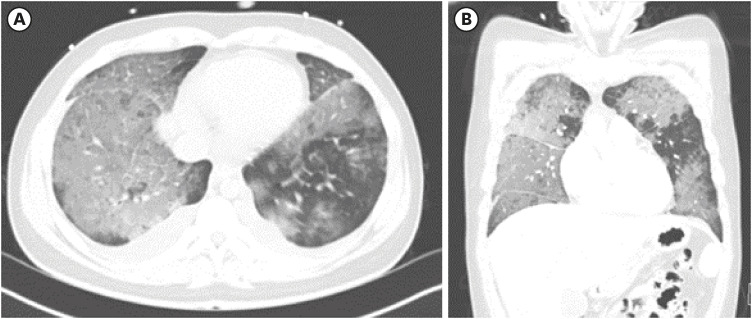

Dr. Moon Kyung Jung: For further evaluation, imaging study was performed. Diffuse ground glass opacities in both lungs and bilateral pleural effusion were detected on chest computed tomography (CT) (

Fig. 1).

Fig. 1

Chest CT of the patient. (A) Cross-sectional image showed bilateral pleural effusion and ill defined patchy ground glass opacities in both lungs (B) coronal image showed patchy ground glass opacities in both lungs and mild interlobular septal thickening.

CT = computed tomography.

Dr. Moon Kyung Jung: In order to rule out infectious origins, respiratory virus multiplex polymerase chain reaction (PCR), COVID-19 PCR, Legionella urinary antigen, Streptococcus pneumoniae urinary antigen, Mycoplasma immunoglobulin M (IgM) and Chlamydia pneumoniae IgM were performed and all of them were negative. Other test results including blood culture, sputum culture and urine culture were also negative.

Dr. Oh Beom Kwon: Since studies to find infectious origins turned out to be negative, bronchoalveloar lavage and pleural effusion drainage was done and these fluids were analyzed.

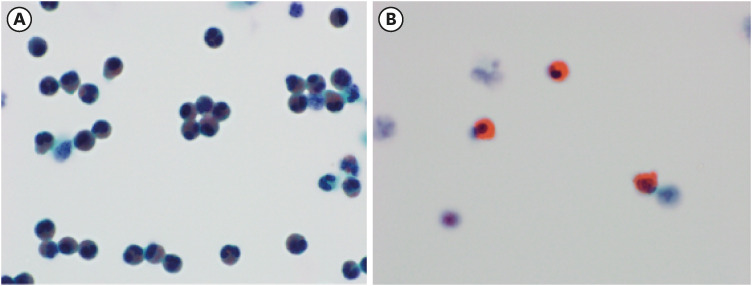

PATHOLOGIC FINDINGS

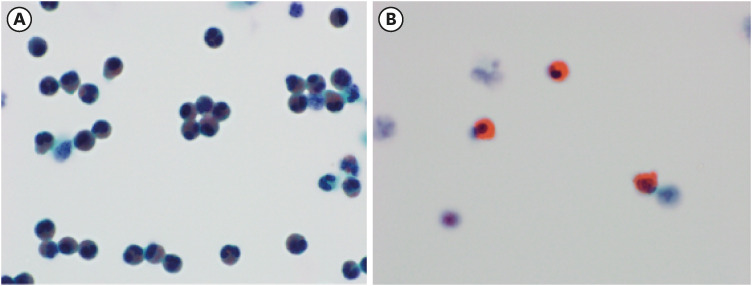

Dr. Moon Kyung Jung: Numerous amount of eosinophils were detected at the bronchoalveolar lavage fluid. (

Fig. 2A) Eosinophilic granules and budding of eosinophils were found at the pleural effusion fluid. (

Fig. 2B)

Fig. 2

Liquid based cytology preparation of the bronchoalveolar lavage fluid and pleural fluid (Papanicolaou stain). (A) Cytology of bronchoalveolar lavage fluid at 1,000× magnification. (B) Cytology of pleural effusion fluid at 1,000× magnification shows bud formation (arrow) in eosinophil.

Overall, eosinophil count was higher at both the bronchoalveolar lavage fluid and pleural effusion fluid.

DISEASE MANAGEMENT

Dr. Moon Kyung Jung: He was prescribed with 0.5 mg/kg oral steroid (prednisolone 30 mg daily) and was tapered to 20, 10 and 7.5 mg within 8 weeks.

PROGNOSIS

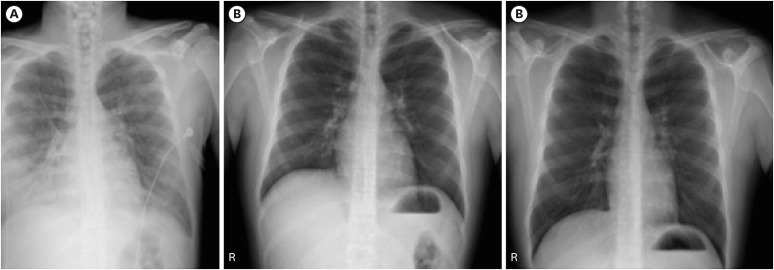

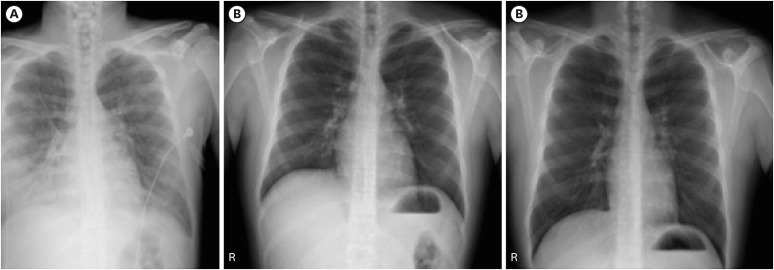

Dr. Moon Kyung Jung: After steroid treatment, symptoms such as dyspnea and cough rapidly improved. Chest X-ray was normal after 2 weeks of prednisolone treatment and remained normal after a month (

Fig. 3). After 8 weeks of treatment, steroid was no longer prescribed and during 1 year of outpatient department follow up period, relapse did not occur.

Fig. 3

Serial chest X ray images from admission to day 30. Chest X ray on day 1 (A), day 14 (B), and day 30 (C) after steroid treatment.

FINAL DIAGNOSIS

Dr. Hyonsoo Joo: Patient had acute onset febrile illness with shortness of breath within 4 days. Diffuse pulmonary infiltrates were found on chest X-ray and bronchoalveolar lavage eosinophil was 56.9%. His symptoms rapidly improved after steroid treatment and there was no relapse after discontinuation of steroid. He did not take any drugs and infection was ruled out. Considering these results all together, we confirmed the final diagnosis of acute eosinophilic pneumonia (AEP).

DISCUSSION

Dr. Young Hyun Song: What is the incidence of AEP and how much does smoking increases the risk of AEP? What is the prognosis of AEP?

Dr. Moon Kyung Jung: AEP is known to be a rare disorder. In one study,

1 18 cases of AEP were identified among 183,000 military personnel resulting in incidence of 9.1 per 100,000 person-years. In this study, new-onset smokers had a significant increased risk of developing AEP compared with controls (odds ratio, 122; 95% confidence interval, 17–1,270).

Dr. Oh Beom Kwon: AEP patients have a very good response to corticosteroids and most of them have clinical improvements within 1–2 days. Some patients spontaneously improved without corticosteroid treatment. However, it is impossible to predict which patients would spontaneously resolve at the time of initial presentation.

23 Recurrence of AEP is rare after discontinuation of corticosteroid.

2

Dr. Seung Hoon Kim: Desquamative interstitial pneumonia (DIP) and respiratory bronchiolitis-associated interstitial lung disease (RB-ILD) are also known to be related with smoking. Since the patient was a smoker, how can these diseases ruled out?

Dr. Oh Beom Kwon: Usually, DIP and RB-ILD patients are between the ages of 30 to 50 and have over 30 pack-year of smoking history.

4 These patients develop symptoms such as dyspnea and cough gradually. However, in this case, the patient was 18 years old and he started smoking 2 weeks prior. Moreover, he had an acute onset shortness of breath and cough. These results were more favorable with AEP than DIP and RB-ILD.

Dr. Yu Jeong Lee: What is the optimal steroid dosage and duration for treatment of AEP? Is it possible to distinguish AEP from other eosinophilic lung diseases such as chronic eosinophilic pneumonia (CEP). Hypereosinophilc syndrome (HES), allergic bronchopulmonary aspergillosis (ABPA) et cetera?

Dr. Hyonsoo Joo: Optimal dose and duration of corticosteroid have not been established. Usually, 60 to 125 mg of intravenous methylprednisolone are given every 6 hours until respiratory failure resolves. Steroids are tapered off over several weeks.

2 In one study, 2-week treatment course starting from oral prednisolone 30 mg twice a day for AEP patients who did not have respiratory failure showed resolution of symptoms and radiological abnormalities.

5

Dr. Oh Beom Kwon: CT findings in AEP can be summarized as the following – ground glass attenuation, smooth interlobular septal thickening, thickening of bronchovascular bundles and pleural effusion.

6 In one study, two observers made a correct diagnosis on average of 61% in eosinophilic lung disease overall and 81% in diagnosing AEP without any clinical information provided.

3 Therefore, in order to make a correct diagnosis, clinical history and laboratory data should also be considered together.

Dr. Hyonsoo Joo: Compared to CEP, AEP patients have no prior asthma history.

2 In this case, patient had atopic dermatitis and asthma history which seems to be an exceptional case. Since he did not relapse after discontinuation of corticosteroid, AEP is a more favorable diagnosis than CEP.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The Case Conference section is prepared from monthly case conference of Department of Internal Medicine, the Catholic University of Korea College of Medicine, Seoul, Korea.

References

1. Shorr AF, Scoville SL, Cersovsky SB, Shanks GD, Ockenhouse CF, Smoak BL, et al. Acute eosinophilic pneumonia among US Military personnel deployed in or near Iraq. JAMA. 2004; 292(24):2997–3005. PMID:

15613668.

2. Sohn JW. Acute eosinophilic pneumonia. Tuberc Respir Dis (Seoul). 2013; 74(2):51–55. PMID:

23483613.

3. Johkoh T, Müller NL, Akira M, Ichikado K, Suga M, Ando M, et al. Eosinophilic lung diseases: diagnostic accuracy of thin-section CT in 111 patients. Radiology. 2000; 216(3):773–780. PMID:

10966710.

4. Ryu JH, Myers JL, Capizzi SA, Douglas WW, Vassallo R, Decker PA. Desquamative interstitial pneumonia and respiratory bronchiolitis-associated interstitial lung disease. Chest. 2005; 127(1):178–184. PMID:

15653981.

5. Rhee CK, Min KH, Yim NY, Lee JE, Lee NR, Chung MP, et al. Clinical characteristics and corticosteroid treatment of acute eosinophilic pneumonia. Eur Respir J. 2013; 41(2):402–409. PMID:

22599359.

6. De Giacomi F, Vassallo R, Yi ES, Ryu JH. Acute eosinophilic pneumonia. causes, diagnosis, and management. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2018; 197(6):728–736. PMID:

29206477.

PDF

PDF Citation

Citation Print

Print

XML Download

XML Download