Abstract

A differential diagnosis of ascites is always challenging for physicians. Peritoneal tuberculosis is particularly difficult to distinguish from peritoneal carcinomatosis because of the similarities in clinical manifestations and laboratory results. Although the definitive diagnostic method for ascites is to take a biopsy of the involved tissues through laparoscopy or laparotomy, there are many limitations in performing biopsies in clinical practice. For this reason, physicians have attempted to find surrogate markers that can substitute for a biopsy as a confirmative diagnostic method for ascites. CA 125, which is known as a tumor marker for gynecological malignancies, has been reported to be a biochemical indicator for peritoneal tuberculosis. On the other hand, the sensitivity of serum CA 125 is low, and CA 125 may be elevated due to other benign or malignant conditions. This paper reports the case of a 66-year-old male who had a moderate amount of ascites and complained of dyspepsia and a febrile sensation. His abdominal CT scans revealed a conglomerated mass, diffuse omental infiltration, and peritoneal wall thickening. Initially, peritoneal tuberculosis was suspected due to the clinical symptoms, CT findings, and high serum CA 125 levels, but non-specific malignant cells were detected on cytology of the ascitic fluid. Finally, he was diagnosed with primary malignant peritoneal mesothelioma after undergoing a laparoscopic biopsy.

A differential diagnosis of ascites has always been a challenge for physicians. In Korea, the prevalence of pulmonary tuberculosis is still higher than in other developed countries, and extrapulmonary tuberculosis, such as peritoneal tuberculosis, intestinal tuberculosis, and tuberculous lymphadenitis, is also common.12 Therefore, physicians should consider the possibility of peritoneal tuberculosis when investigating the cause of ascites.

Initially, it is difficult to diagnose peritoneal tuberculosis because its clinical manifestations may be similar to other diseases with ascites, including malignancies. Although ascitic fluid analysis, including the serum ascites albumin gradient and cell counts, imaging studies, and serum laboratory tests without histopathology findings, are generally used to make a differential diagnosis of ascites, they are not sufficient to confirm the origin of ascites. To compensate for these limitations, many recent case reports have suggested that serum CA 125, a tumor marker of gynecologic malignancies, can aid in a differential diagnosis of peritoneal tuberculosis as a cause of ascites.3 This paper reports a rare case that was ultimately diagnosed as malignant peritoneal mesothelioma despite the strong initial suspicion of peritoneal tuberculosis due to the marked elevation of the serum and peritoneal CA 125 levels and the clinical manifestations.

A 66-year-old male patient without a specific medical history was referred from a local clinic due to abdominal distension. The patient complained of abdominal discomfort and distension for 2 or 3 weeks. He also complained of anorexia, dyspepsia, and a mild chilling sensation. Esophagogastroduodenoscopy and colonoscopy were performed at a local clinic. Erosive gastritis was noted during an upper endoscopic examination and a small hyperplastic polyp was detected by colonoscopy. On abdominal ultrasonography, the intraabdominal organs were non-specific, but a moderate amount of ascites was noted. For that reason, abdominal CT was performed and the patient was referred for further evaluation to determine the cause of the ascites and treatment. His smoking history was 30 pack years and he occasionally drank small amounts of alcohol; there was no family history of malignancy. His occupation was a farmer and he had sometimes worked at construction sites in his younger years.

His initial vital signs were blood pressure of 140/81 mmHg, heart rate of 105 beats/min, respiratory rate of 20 breaths/min, and body temperature of 37℃. The patient's body weight was 63.6 kg, and his height was 176 cm. A rapid decrease in body weight had not occurred recently. On a physical examination, abdominal distension without tenderness and fluid shifting were noted, and a dull sound on percussion was also heard. The laboratory results revealed the following: a white blood cell count of 9,200 cells/µL, hemoglobin of 12.1 g/dL, platelet count of 5.59×105 cells/µL, total bilirubin level of 0.9 mg/dL, AST level of 28 IU/L, ALT level of 19 IU/L, ALP level of 203 U/L (reference range: 35–130 U/L), LDH level of 268 U/L (reference range: 135–225 U/L), GGT level of 119 IU/L (reference range: 10–71 IU/L), albumin level of 3.1 g/dL (reference range: 3.5–5.2 g/dL), PT of 12.7 seconds, CRP level of 9.03 mg/dL (reference range: 0–0.5 mg/dL), and erythrocyte sedimentation rate of 87 mm/hr (reference range: 0–20 mm/hr). The viral markers of hepatitis B, hepatitis C and human immunodeficiency virus were all negative. Regarding the tumor markers, the results showed an AFP level of 2.6 ng/mL, CEA level of 0.11 ng/mL, CA 19–9 <2.00 U/mL, and an elevated serum CA 125 level of 100.8 µg/mL (reference range: 0–35 µg/mL). Interferon-gamma release assays and tuberculin skin test or Mantoux test were not performed. The chest X-ray and simple abdominal examinations revealed no active lesions (Fig. 1). Electrocardiography was also non-specific.

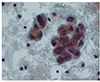

Diagnostic paracentesis was performed to evaluate the ascitic fluid, which revealed a white blood cell of 1,400 cells/mm3 (lymphocyte 53%, poly 42%), red blood cell count of 1,000 cells/mm3, protein level of 5.5 g/dL, albumin level of 2.5 g/dL, LDH level of 926 IU/L (reference range: 150–470 IU/L), glucose level of 146 mg/dL (reference range: 40–70 mg/dL), and adenosine deaminase (ADA) level of 69.1 U/L (reference range: <39 U/L). The peritoneal CA 125 levels were 651.5 µg/mL. The abdominal CT scans performed at a local clinic showed a 4.4×5.5 cm conglomerated mass among the portal vein, pancreas neck, and liver (Fig. 2). In addition, diffuse omental infiltration, a moderate amount of ascites and peritoneal thickening were observed.

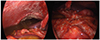

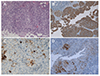

A radiologist of our center initially suspected tuberculous lymphadenitis and peritoneal tuberculosis, but the result of AFB staining of the ascitic fluid was negative. Suspicious malignant cells were detected during a cytology examination of the ascitic fluid (Fig. 3). Therefore, a laparoscopic biopsy was performed to confirm the diagnosis. A large amount of ascites and multiple whitish patch nodules within the whole peritoneum, omentum, and bowel walls were seen (Fig. 4). A surgeon who performed the laparoscopic biopsy also strongly suspected peritoneal tuberculosis. Biopsies were performed on five points of the peritoneum, mesentery, and omentum. Despite the high likelihood of peritoneal tuberculosis and the patient's complaint of a rapid increase in ascites, the authors recommended waiting for the biopsy results to confirm the diagnosis. Finally, immunohistochemical staining of the specimen showed that these tissues were reactive for cytokeratin (CK), CK 7, and focally calretinin positive and negative to CK 20, CK 5.6, estrogen receptor, CEA, human melanoma black-45, and vimentin (Fig. 5). These results demonstrated malignant mesothelioma in the peritoneum. The amount of ascites increased rapidly and multiple therapeutic paracenteses were performed to relieve the abdominal pain. Thereafter, although the patient was referred to a tertiary hospital for systemic chemotherapy, he died of severe sepsis with increased pleural effusion before starting chemotherapy.

Peritoneal tuberculosis is a rare form of extrapulmonary tuberculosis. Mycobacterium tuberculosis can spread to the peritoneum through the gastrointestinal tract via the mesenteric lymph nodes or directly from the blood, lymph, and fallopian tube.4 Generally, a microbiological diagnosis of peritoneal tuberculosis is very slow and inadequate. Owing to the lack of characteristic clinical features of peritoneal tuberculosis, it can be confused easily with peritoneal carcinomatosis, particularly in the elderly. Analysis of the ascitic fluid of peritoneal tuberculosis shows lymphocyte-predominant exudative features with a low serum ascites-albumin gradient (<1.1) as well as elevated levels of total protein, LDH, and CA 125. In addition, high ADA levels of ascitic fluid are a good parameter for detecting peritoneal tuberculosis.5 On the other hand, all these results cannot definitively confirm a diagnosis of peritoneal tuberculosis. In the present case, the patient complained of anorexia, dyspepsia, and a mild chilling sensation. A study of the ascitic fluid revealed lymphocyte-predominant exudative fluid with a low serum ascites-albumin gradient (0.6). The ascitic ADA level was also elevated (69.1 U/L), as were the serum and peritoneal CA 125 levels (100.8 µg/mL and 651.6 µg/mL, respectively). These results led to the suspicion of peritoneal tuberculosis.

In this case, interferon-gamma release assays, which are useful for a diagnosis of extrapulmonary tuberculosis and latent tuberculosis infections, were not performed because of the restriction of the national health insurance and the low sensitivity and specificity for peritoneal tuberculosis. In particular, the sensitivity and specificity of the tuberculin skin test are relatively low due to the injection of a Mycobacterium bovis bacille Calmette-Guérin vaccine in Korea; hence, a tuberculin skin test was not conducted.

Table 1 shows the published cases that had difficulty in a differential diagnosis between peritoneal tuberculosis and malignant peritoneal mesothelioma, and they were finally diagnosed as malignant peritoneal mesothelioma by the histopathology results from a biopsy.678 With the exception of the present case, the CA 125 levels were not evaluated in the other cases. This may be because the patients involved in these cases were male. An association with exposure to asbestos was observed in the only one case. Melero et al.8 prescribed an empirical antituberculosis treatment to a young male with prolonged fever, leukocytosis and a septated peritoneal exudate, but the patient's symptoms did not improve. Finally, malignant peritoneal mesothelioma was confirmed through an exploratory laparotomy. After a definitive diagnosis as malignant peritoneal mesothelioma, all the patients expired in the short-term period regardless of systemic chemotherapy. Table 2 lists the similarities and differences in clinical manifestations and radiologic findings of peritoneal tuberculosis and malignant peritoneal mesothelioma.9

CA 125 is a glycoprotein derived from the coelomic epithelium and found in normal tissue. The glycoprotein is usually elevated in the presence of epithelial ovarian carcinoma. On the other hand, elevation of the serum CA 125 levels can also be seen in some non-malignant and non-gynecological diseases, such as autoimmune diseases, pancreatitis, peritonitis, congestive heart failure, chronic renal failure, liver granulomatosis, pelvic inflammatory disease, endometriosis, pregnancy, and even during menstruation.10 Many reports have reported an association between peritoneal tuberculosis and high serum CA 125.1112 In addition, elevated serum CA 125 levels have a high predictive value for a diagnosis of peritoneal tuberculosis, whereas decreased serum CA 125 levels can be used to evaluate the efficacy of therapy in peritoneal tuberculosis.3111213 Some studies reported that while the serum CA 125 levels may be elevated in patients with peritoneal tuberculosis (approximately 10- to 20-fold higher than normal values), they would likely be much higher in patients with peritoneal carcinomatosis (approximately 60-fold higher than normal values).1415 Some authors have suggested a short course of empirical anti tuberculosis treatment before surgery to arrive at the final diagnosis, which might be helpful in cases of ascites with moderately elevated CA 125.15

CA 125 has several limitations. The sensitivity of CA 125 is less than optimal. As mentioned previously, the CA 125 levels may also be elevated in many benign conditions. In the present case, the clinical symptoms and signs as well as the serum CA 125 levels were indicative of peritoneal tuberculosis, but the final diagnosis was primary malignant peritoneal mesothelioma, which is very aggressive and lethal. A definitive diagnosis and proper treatment would have been delayed if the anti-tuberculosis treatment had been given empirically. Thakur et al.11 suggested that elevated serum CA 125 levels in peritoneal tuberculosis might be related to ovarian involvement because there are no reports of tuberculous ascites with elevated serum CA 125 levels in male patients. Indeed, elevated serum and peritoneal CA 125 levels in male patients were not associated with peritoneal tuberculosis.

Recently, some studies reported that high serum CA 125 levels may suggest, but not necessarily be diagnostic of fatal malignant mesothelioma.1617 There is no accepted tumor marker for malignant mesothelioma in clinical practice. Some studies have proposed that soluble mesothelin could be a relevant tumor marker of malignant mesothelioma and that the baseline serum mesothelin level might be an independent predictor of the overall survival.18 Unfortunately, most medical institutions in Korea are unable to evaluate the mesothelin concentration. Recent studies have shown that mesothelin-CA 125 binding has high affinity and is co-expressed in mesothelioma.1920 These findings suggest that elevated serum CA 125 levels, which are used widely in clinical practice, may be sensitive for predicting the disease progression of malignant mesothelioma and imply the use of serum CA 125 as a potential prognostic marker.

This case describes a rare disease, malignant peritoneal mesothelioma, without asbestos exposure. Korea is still an endemic area of Mycobacterium tuberculosis. In this case, peritoneal tuberculosis was first suspected based on the CA 125 levels and clinical manifestations until histopathological confirmation. Therefore, this case demonstrates that all possibilities should be considered in patients with ascites of an unknown cause until a definite diagnosis is made regardless of the high CA 125 levels or elevation of other tumor markers. In addition, elevated serum CA 125 in males with ascites of an unknown cause may be related to other malignancies, including malignant mesothelioma.

Figures and Tables

Fig. 1

Chest X-ray and simple abdomen scan images. (A) The chest X-ray shows increased bronchovascular markings in the right lower lung filed, but no active lung disease and pleural effusion. (B) The centralized bowel gases are noted due to massive ascites in the simple abdomen erect view.

Fig. 2

Contrast-enhanced computed tomography images of the abdomen show a 4.4×5.5 cm conglomerated mass (yellow arrows) among the portal vein, pancreas neck, and liver. Diffuse omental infiltration, a moderate amount of ascites and peritoneal thickening are also revealed.

Fig. 3

Aspiration of ascites shows suspicious malignant cells, which were finally revealed as atypical mesothelial cells (ThinPrep 2000 System; Cytyc Corp., Marlborough, MA, USA) (Papanicolaou stain, ×400).

Fig. 4

Gross photographs during laparoscopic biopsy reveal a large amount of ascites and multiple whitish patch nodules within the whole peritoneum, omentum, and bowel walls.

Fig. 5

Histology specimen shows malignant mesothelial cells, epitheloid type (A: H&E, ×100). Immunohistochemical staining of the specimens is reactive for cytokeratin and cytokeratin-7 and focally positive for calretinin, confirming the diagnosis of malignant peritoneal mesothelioma (B: cytokeratin, ×100; C: cytokeratin-7, ×200; D: calretinin, ×100).

References

1. Lee JY. Diagnosis and treatment of extrapulmonary tuberculosis. Tuberc Respir Dis (Seoul). 2015; 78:47–55.

2. Kim JH, Yim JJ. Achievements in and challenges of tuberculosis control in South Korea. Emerg Infect Dis. 2015; 21:1913–1920.

3. Mas MR, Cömert B, Sağlamkaya U, et al. CA-125; a new marker for diagnosis and follow-up of patients with tuberculous peritonitis. Dig Liver Dis. 2000; 32:595–597.

4. Rasheed S, Zinicola R, Watson D, Bajwa A, McDonald PJ. Intra-abdominal and gastrointestinal tuberculosis. Colorectal Dis. 2007; 9:773–783.

5. Kocaman O. Understanding tuberculous peritonitis: a difficult task to overcome. Turk J Gastroenterol. 2014; 25:79–80.

6. Shih CA, Ho SP, Tsay FW, Lai KH, Hsu PI. Diffuse malignant peritoneal mesothelioma. Kaohsiung J Med Sci. 2013; 29:642–645.

7. Torrejón Reyes PN, Frisancho O, Gómez A, Yábar A. Malignant peritoneal mesothelioma. Rev Gastroenterol Peru. 2010; 30:82–87.

8. Melero M, Lloveras J, Waisman H, Elsner B, Baldessari E. Malignant peritoneal mesothelioma. An infrequent cause of prolonged fever syndrome and leucocytosis in a young adult. Medicina (B Aires). 1995; 55:48–50.

9. Yin WJ, Zheng GQ, Chen YF, et al. CT differentiation of malignant peritoneal mesothelioma and tuberculous peritonitis. Radiol Med. 2016; 121:253–260.

10. Silberstein LB, Rosenthal AN, Coppack SW, Noonan K, Jacobs IJ. Ascites and a raised serum CA 125--confusing combination. J R Soc Med. 2001; 94:581–582.

11. Thakur V, Mukherjee U, Kumar K. Elevated serum cancer antigen 125 levels in advanced abdominal tuberculosis. Med Oncol. 2001; 18:289–291.

12. Seo BS, Hwang IK, Ra JE, Kim YS. A patient with tuberculous peritonitis with very high serum CA 125. BMJ Case Rep. 2012; 2012:bcr2012006382.

13. Kaya M, Kaplan MA, Isikdogan A, Celik Y. Differentiation of tuberculous peritonitis from peritonitis carcinomatosa without surgical intervention. Saudi J Gastroenterol. 2011; 17:312–317.

14. Choi CH, Kim CJ, Lee YY, et al. Peritoneal tuberculosis: a retrospective review of 20 cases and comparison with primary peritoneal carcinoma. Int J Gynecol Cancer. 2010; 20:798–803.

15. Bae SY, Lee JH, Park JY, et al. Clinical significance of serum CA-125 in Korean females with ascites. Yonsei Med J. 2013; 54:1241–1247.

16. Kebapci M, Vardareli E, Adapinar B, Acikalin M. CT findings and serum ca 125 levels in malignant peritoneal mesothelioma: report of 11 new cases and review of the literature. Eur Radiol. 2003; 13:2620–2626.

17. Gube M, Taeger D, Weber DG, et al. Performance of biomarkers SMRP, CA125, and CYFRA 21-1 as potential tumor markers for malignant mesothelioma and lung cancer in a cohort of workers formerly exposed to asbestos. Arch Toxicol. 2011; 85:185–192.

18. Hollevoet K, Nackaerts K, Gosselin R, et al. Soluble mesothelin, megakaryocyte potentiating factor, and osteopontin as markers of patient response and outcome in mesothelioma. J Thorac Oncol. 2011; 6:1930–1937.

PDF

PDF ePub

ePub Citation

Citation Print

Print

XML Download

XML Download