Abstract

Objective

To compare the clinical characteristics and the prognosis between emergency hysterectomy and conservative treatment following postpartum hemorrhage.

Methods

Primary postpartum hemorrhage was identified in 68 patients who treated in our hospital after delivery at Inje University Busan Paik Hospital and local hospital between 2004 and 2011. 29 patients of these were performed emergency hysterectomy and 39 patients conserved uterus. Clinical characteristics and prognosis of postpartum hemorrhage were reviewed and analyzed with medical records.

Results

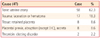

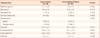

There were no difference of mean age, body mass index, parity, causes of postpartum hemorrhage (PPH), and labor induction between hysterectomy and conservative treatment. The hysterectomy patients had lower blood pressure (83.62/48.01 mm Hg ± 19.16/21.68 mm Hg vs. 96.10/64.12 mm Hg ±16.17/22.8 mm Hg), higher heart rate (114 ± 21.68/min vs. 96.10 ± 22.8/min), and lower hemoglobin concentration (6.99 ± 3.06 g/dL vs. 8.34 ± 2.1 g/dL) than the patients with conservative treatment (P=0.0007, 0.0017, 0.0358, respectively). Hysterectomy group had a longer hospital stay, much more management in intensive care unit (ICU) and more complications than conservative group (P=0.0004, <0.0001, 0.0049, respectively).

Conclusion

If patients with postpartum hemorrhage were hemodynamically unstable, it is more possible to be performed the emergency hysterectomy. Emergency hysterectomy was associated with a longer hospital stay and more complications. Therefore we consider that early recognition of PPH with frequent monitoring of vital sign, uterine contraction and vaginal bleeding is able to reduce unnecessary hysterectomy and minimize potentially serious outcomes.

Figures and Tables

References

1. Hill K, Thomas K, AbouZahr C, Walker N, Say L, Inoue M, et al. Estimates of maternal mortality worldwide between 1990 and 2005: an assessment of available data. Lancet. 2007. 370:1311–1319.

2. Khan KS, Wojdyla D, Say L, Gulmezoglu AM, Van Look PF. WHO analysis of causes of maternal death: a systematic review. Lancet. 2006. 367:1066–1074.

3. American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. ACOG Practice Bulletin: Clinical Management Guidelines for Obstetrician-Gynecologists Number 76, October 2006: postpartum hemorrhage. Obstet Gynecol. 2006. 108:1039–1047.

4. Dildy GA 3rd. Postpartum hemorrhage: new management options. Clin Obstet Gynecol. 2002. 45:330–344.

5. Seo K, Park MI, Kim SY, Park JS, Han YJ. Changes of maternal mortality ratio and the causes of death in Korea during 1995-2000. Korean J Obstet Gynecol. 2004. 47:2345–2350.

6. Upadhyay K, Scholefield H. Risk management and medicolegal issues related to postpartum haemorrhage. Best Pract Res Clin Obstet Gynaecol. 2008. 22:1149–1169.

7. Combs CA, Murphy EL, Laros RK Jr. Factors associated with postpartum hemorrhage with vaginal birth. Obstet Gynecol. 1991. 77:69–76.

8. Bonnar J. Massive obstetric haemorrhage. Baillieres Best Pract Res Clin Obstet Gynaecol. 2000. 14:1–18.

9. American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. ACOG educational bulletin. Postpartum hemorrhage. Number 243, January 1998 (replaces No. 143, July 1990). Int J Gynaecol Obstet. 1998. 61:79–86.

10. Smith JR, Brennan BG. Postpartum hemorrhage [Internet]. c2012. cited 2012 Nov 20. New York: WebMD LLC;Available from: http://emedicine.medscape.com/article/275038-overview.

11. Gahres EE, Albert SN, Dodek SM. Intrapartum blood loss measured with Cr 51-tagged erythrocytes. Obstet Gynecol. 1962. 19:455–462.

12. Kodkany B, Derman R. B-Lynch C, Keith L, Lalonde A, editors. Pitfalls in assessing blood loss and decision to transfer. A textbook of postpartum hemorrhage. 2006. Duncow (UK): Sapiens;35–45.

13. Oyelese Y, Ananth CV. Postpartum hemorrhage: epidemiology, risk factors, and causes. Clin Obstet Gynecol. 2010. 53:147–156.

14. Blomberg M. Maternal obesity and risk of postpartum hemorrhage. Obstet Gynecol. 2011. 118:561–568.

15. Mercier FJ, Van de Velde M. Major obstetric hemorrhage. Anesthesiol Clin. 2008. 26:53–66.

16. Drucker M, Wallach RC. Uterine packing: a reappraisal. Mt Sinai J Med. 1979. 46:191–194.

17. Bakri YN, Amri A, Abdul Jabbar F. Tamponade-balloon for obstetrical bleeding. Int J Gynaecol Obstet. 2001. 74:139–142.

18. Johanson R, Kumar M, Obhrai M, Young P. Management of massive postpartum haemorrhage: use of a hydrostatic balloon catheter to avoid laparotomy. BJOG. 2001. 108:420–422.

19. Katesmark M, Brown R, Raju KS. Successful use of a Sengstaken-Blakemore tube to control massive postpartum haemorrhage. Br J Obstet Gynaecol. 1994. 101:259–260.

20. Chan C, Razvi K, Tham KF, Arulkumaran S. The use of a Sengstaken-Blakemore tube to control post-partum hemorrhage. Int J Gynaecol Obstet. 1997. 58:251–252.

21. Condous GS, Arulkumaran S, Symonds I, Chapman R, Sinha A, Razvi K. The "tamponade test" in the management of massive postpartum hemorrhage. Obstet Gynecol. 2003. 101:767–772.

22. Tamizian O, Arulkumaran S. The surgical management of postpartum haemorrhage. Curr Opin Obstet Gynecol. 2001. 13:127–131.

23. B-Lynch C, Coker A, Lawal AH, Abu J, Cowen MJ. The B-Lynch surgical technique for the control of massive postpartum haemorrhage: an alternative to hysterectomy? Five cases reported. Br J Obstet Gynaecol. 1997. 104:372–375.

24. Yucel O, Ozdemir I, Yucel N, Somunkiran A. Emergency peripartum hysterectomy: a 9-year review. Arch Gynecol Obstet. 2006. 274:84–87.

25. Gabbe SG, Simpson JL, Niebyle JR, Galan HL, Goetzl L, Jauniaux ER, et al. Obstetrics: normal and problem pregnancies. 2007. 6th ed. Philadelphia (PA): Churchill Livingstone.

26. Bose P, Regan F, Paterson-Brown S. Improving the accuracy of estimated blood loss at obstetric haemorrhage using clinical reconstructions. BJOG. 2006. 113:919–924.

27. Singh S, McGlennan A, England A, Simons R. A validation study of the CEMACH recommended modified early obstetric warning system (MEOWS). Anaesthesia. 2012. 67:12–18.

28. American Academy of Pediatrics. American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. Guidelines for perinatal care. 2008. 6th ed. Washington, DC: American Academy of Pediatrics and American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists.

PDF

PDF ePub

ePub Citation

Citation Print

Print

XML Download

XML Download