Abstract

Objective

The purpose of this study was to evaluate postoperative pain of total laparoscopic hysterectomy (TLH) compared with vaginal hysterectomy (VH).

Methods

From June 2010 to August 2010, 122 patients were enrolled, of whom 56 underwent TLH and 66 underwent VH for benign diseases at Kangnam Sacred Heart Hospital. Postoperative pain degree was compared in non-randomized, prospective method and preoperative, intraoperative, postoperative characteristics were considered. Postoperative pain was measured using the visual analog scale (VAS) score at 1-hour, 1-day, 3-day postoperative periods and the additional consumption of analgesic units (vials and tablets) required by patients for pain relief at all hospital stay.

Results

For the first 3 postoperative days, the median total consumption of analgesics was considerably lower in the TLH group than in the VH group (pethidine, P<0.05; non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drug [Ketorolac Tromethamine], P<0.05). The VAS score also was higher for the VH group than in the TLH group (VAS 1-hour, P<0.05; VAS 1-day, P<0.05; VAS 3-day, P<0.05). No significant difference was found between groups in respect to preoperative, intraoperative and postoperative characteristics except operation time, prior intra-abdominal surgery and pelvic adhesion.

Hysterectomy is one of the most common surgical procedure worldwide [1,2]. Annually 600,000 hysterectomies are carried out in the USA, more than 32,000 hysterectomies in Australia, and 60,000 hysterectomies in France [3-5].

According to surgical approach, hysterectomy is divided into abdominal approach, vaginal approach, and laparoscopic approach.

Abdominal and vaginal hysterectomies have been performed for centuries. About 20 years ago, the laparoscopic approach to hysterectomy was introduced by Reich [6], and it has been evolving since then [7].

Until now, many studies attempted to evaluate the effectiveness of hysterectomy and most of those studies have not mentioned postoperative pain [8-10].

However, it is necessary to study postoperative pain because postoperative pain has made most patients who undergo surgery fearful and undoubtedly, they would like to avoid experiencing pain. For this reason, postoperative pain became an object of this study. We report our experiences here with total laparoscopic hysterectomy (TLH) at Kangnam Sacred Heart Hospital in the year 2010 in comparison to vaginal hysterectomy (VH) in terms of the difference in postoperative pain.

Prospective non-randomized case-control study to compare patients undergoing total laparoscopic hysterectomy and women undergoing vaginal hysterectomy for benign diseases was designed for this study.

From June 2010 to August 2010, the records of 122 women who had TLH or VH for benign diseases in Kangnam Sacred Heart Hospital were reviewed by prospective analysis.

One hundred twenty-two patients were enrolled, of whom 56 underwent total laparoscopic hysterectomy and 66 underwent vaginal hysterectomy.

Procedures were performed by 3 skilled gynecological surgeons in our department and were not limited to those specializing in laparoscopy or vaginal procedures. The skilled gynecological surgeon is defined as the person who has a minimum of 5 years' experience in gynecological surgery and has performed at least 100 gynecological surgery procedures per year. The surgical route was decided by whether the uterus was mobile when traction was done by clamping the cervix with tenaculum. VH was performed when mobile, whereas TLH was performed in other cases.

The patient was placed in a supine position. Under general anesthesia, the patient's position was changed to a lithotomic position. The skin painting and draping was done in the usual manners. The vaginal mucosa at the junction of the cervix was incised with a scalpel around the entire cervix. The operator dissected the bladder with a finger from the uterus at the vesicouterine peritoneal fold level. The fold was grasped by a silk suture after being incised. The peritoneum of the cul-de-sac was exposed and incised also. The ligaments of the uterus were exposed partially on each side. The uterosacral ligaments were clamped, cut and tied with Vicryl 1-0. And then, both cardinal ligaments were done in the same way.

The round ligaments were clamped with the kelly clamp and incised close to the uterine fundus and tied with Vicryl 1-0 on each side. The second ties of these pedicles were done with Vicryl 1-0. The uterus was removed out of the pelvic cavity through the vagina. The peritoneum was reestablished with chromic 1-0.

The definition of TLH in this study was limited in that the uterus must be removed completely laparoscopically and vaginal incision had to be closed by laparoscopic sutures.

With the lithotomic position, the abdomen and suprapubic areas of the patient were painted with potadine solution and draped in the usual manner under general anesthesia. The small skin incision was made just below the umbilicus and the abdominal wall was picked up manually.

The 11 mm trocar was inserted into the umbilical incision wound and peritoneal cavity was filled with CO2 gas to a limited pressure of 12 mm Hg. After the same method, three 5 mm trocars were placed laterally left and right, and in the middle of the lower abdomen. The uterine fundus was lifted up by using a "uterine elevator." The round ligaments were cut and electrocoagulated by electrosurgical devices. The leaves of the broad ligaments were opened anteriorly to the vesicouterine fold and posteriorly to the uterosacral ligaments and across the posterior lower uterine segment. The tubes and suspensory ligaments or infundibulopelvic ligaments both were electrocoagulated. The filmy tissues surrounding the uterine vessels were skeletonized by dissecting the tissues away from the uterine vessels.

The uterine vessels were clamped, divided and ligated with Vicryl 1-0. And then the cervicovaginal junction was cut by electrosurgical devices and the uterus was removed from the vagina circumferentially. The suture with Vicryl 1-0 was carried out over the vaginal stump. After rinsing, a drain is placed.

The laparoscopic and trocar sleeve were removed and CO2 gas was removed. The incision wound was closed layer by layer.

Patients were excluded from this study if they had a confirmed or suspected malignant disease, pelvic inflammatory disease or severe endometriosis. Patients who had vaginal prolapse higher than the first degree also were excluded from this study.

For each patient, we recorded preoperative parameters including patient's age, weight, parity, body mass index (BMI), prior intra-abdominal surgery history, intraoperative parameters including complications (bladder, ureter or bowel injury), estimated blood loss, time of operation (from the first incision until the last suture), uterine weight, concomitant unilateral or bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy, concomitant vaginal repair, conversion to laparotomy, and postoperative parameters including length of hospital stay, fever (temperature >38℃, after the first 24 postoperative hours), reduction of hemoglobin (before surgery and on the first postoperative day), blood transfusion.

For pain management, intraoperatively analgesics consisting of fentanyl (4-8 µg/kg/hr intravenously), and patient controlled analgesia (PCA) was given immediately after surgery, which continued for 24 hours. PCA is composed with combinations of fentanyl 20 µg/kg, non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drug (NSAIDs) (Ketorolac Tromethamine) 3.0 mg/kg and antiemetics (ondansetron) 8 mg (in 100 mL normal saline in a premixed bag). As per our protocol, the PCA was continued for the first 48 postoperative hours. The program allowed a patient bolus of 2 mL available every 15 minutes. In addition, 30 mg of non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (Ketorolac Tromethamine) or 50 mg of tramadol was administered intravenously and regularly (q 8 hours) during the 2-day postoperative period. From the next day, tablet (Ketorolac Tromethamine 10 mg or Tramadol 50 mg) was given regularly (q 8 hours) during the hospital stay.

Consumption of analgesics was defined as the number of required analgesics and a total amount of required analgesic units (dose) for pain relief. The used analgesics were pethidine, NSAIDs (Ketorolac Tromethamine), and tramadol. To evaluate postoperative pain, we used the visual analog scale (VAS) score at 1-hour, 1-day, 3-day postoperative period and the additional consumption of analgesic units (vials and tablets) required by patients for pain relief at all hospital stay. The higher VAS score means that the pain felt after operation is more severe.

Hospital discharge was decided by the restarted bowel motility, lack of urinary problems, absence of temperature (<37℃), well-controlled pain on oral medications and improved daily activity.

The data was analyzed with SPSS ver. 13.0 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA) software, using the Student's t-test for comparison of continuous data, and correlated by χ2-test or Fisher's exact test for nominal data.

A P-value < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

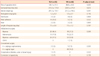

There is no difference in patient's characteristics such as age, parity, and BMI between two groups (P=0.05). However, the history of Prior intra-abdominal surgery is much more in TLH group than in VH group ( 19 [33%] vs. 4 [6.1%], P<0.024) (Table 1).

No significant difference was found between groups with respect to intraoperative and postoperative complications rates, estimated blood loss, fever, uterine weight, length of hospital stay (Table 2).

However, TLH is associated with a longer operation time (TLH, 126.1 ± 31.5 minutes vs. VH, 88.8 ± 20.0 minute; P=0.000), more prior intra-abdominal surgery (TLH, 33.9% vs. VH, 6.1%; P<0.05), more pelvic adhesion (TLH, 25.0% vs. VH, 7.5%; P<0.05).

There were no cases of bowel injuries. The reduction of hemoglobin was not statistically different, but TLH shows a greater drop in hemoglobin level than VH (TLH, 1.2 ± 0.7 g/dL vs. VH, 1.0±0.7 g/dL; P=0.116). We had one conversion of intended TLH to abdominal surgery (TLH, 1.7% vs. VH, 0%; P=0.159), because of bladder tear during TLH, which was repaired. The patient had severe pelvic adhesion due to previous abdominal surgery (Table 2).

Postoperative pain was evaluated by measuring additional consumption of analgesics and VAS score.

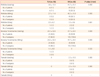

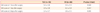

For the first 3 postoperative days, the mean total consumption of analgesics was significantly reduced in patients who underwent TLH compared with patients who had gone under VH. Requirements of median total pethidine was reduced (TLH, 3.6 ±13.0 mg vs. VH, 41.7 ± 31.1 mg; P=0.000), median total NSAIDs (Ketorolac Tromethamine) was reduced (TLH, 24.1± 32.6 mg vs. VH, 47.7 ± 24.1 mg; P=0.000), and median total tramadol was reduced (TLH, 0 mg vs. VH, 2.3 ±10.5 mg, P=0.083) in patients who underwent TLH compared to patients who had VH (Table 3).

Also, the mean VAS score was considerably lower in the TLH group than in the VH group. The mean VAS score at 1 hour after surgery was lower (TLH, 5.6 ± 0.8 vs. VH, 5.9 ± 0.9; P<0.05), the mean VAS score at 1 day after surgery was lower (TLH, 3.9 ± 0.8 vs. VH, 4.2 ± 0.8; P<0.05) and the mean VAS score at 3 days after surgery was significantly lower (TLH, 2.4 ± 0.7 vs. VH, 2.8 ± 0.5; P=0.000) in the TLH group than in the VH group (Table 4).

TLH requires lower dose of analgesics and results in lower VAS score in comparison to VH.

The International Association for the Study of Pain defines pain as "an unpleasant sensory and emotional experience associated with actual or potential tissue damage, or described in terms of such damage [11]." And it is axiomatic that there can be no surgery without corresponding postoperative pain because tissue trauma and the release of potent mediators of inflammation consequently are expected [12].

Due to repeated tissue damage and continual irritation during surgery, the peripheral and central nerves become sensitive, leading to amplification of pain after surgery. Patients who have had surgery performed on the same area will have different degrees of pain depending on the surgical method, and each patient will experience variation in pain as time lapses.

There is now a general consensus that vaginal hysterectomy should be considered the gold standard if compared with abdominal hysterectomy in case of benign uterine pathologies with uterus that is mobile and not large and without adnexal pathologies [13,14]. Such a superiority, however, is not so clearly demonstrated over laparoscopic hysterectomy [15,16].

In a previous study of this kind completed 6 years ago. Nascimento et al. [17] compared 100 patients submitted to TLH and VH. Analgesic requirements were found to be significantly lower in the TLH group.

As a result of a similar study, laparoscopic hysterectomy provides an advantage over vaginal hysterectomy in terms of postoperative pain [18,19].

More recently, in a study randomizing a total of 60 patients to either TLH or VH, Candiani et al. [20] reported that women undergoing laparoscopy had better pain scores and shorter time of postoperative analgesia use than those undergoing vaginal surgery.

The current study also demonstrates that, compared with the vaginal approach, total laparoscopic hysterectomy is associated with less postoperative pain, and with a reduction in the need of additional postoperative analgesic doses.

In this study, for postoperative pain control, all the patients received the same method of pain control using PCA, and postoperative variation in pain intensity was measured using VAS score at scheduled intervals. Any additional dose amount of analgesics and the number of times administered was taken into account.

In our study comparing laparoscopic hysterectomy and vaginal hysterectomy, postoperative pain score on day 0, 1, 3 after surgery and the number of analgesic request were higher in the VH group. Consequently, laparoscopic hysterectomy results in less postoperative pain compared with vaginal hysterectomy.

Also, in a study published in 2008, Schindlbeck et al. [21] found lower consumption of analgesics in TLH compared to VH, similar to our findings.

Several possible explanations can be hypothesized to explain our data in favor of laparoscopy. First, different operative positions are required to perform vaginal and laparoscopic procedures: in particular, the inferior limbs are placed in a more physiological position during TLH. Second, unlike a laparoscopic procedure, vaginal surgery requires applying a frequent downward traction on the uterus. Third, we used electrosurgical devices to coagulate and dissect tissues during LH; whereas VH was performed using clamps, scissors, and tying knots, according to the traditional vaginal techniques. Regarding this latter possible explanation, some studies have consistently shown how the implementation of electrosurgical technology in vaginal surgery resulted in a significant reduction of postoperative pain [22,23].

Our study reveals that TLH is associated with less postoperative pain when compared with VH overall. Consequently, TLH is an excellent surgical method in terms of postoperative pain. However, laparoscopic hysterectomy is unlikely to be considered cost effective compared with a vaginal hysterectomy. In previously reported comparisons of laparoscopic and vaginal hysterectomy, the main difference related to operating room cost, which reflected differences in operation times and the multiple use of disposable equipment in laparoscopic procedures [24].

If surgeons use mostly reusable equipment instead of relatively expensive disposables, the additional cost of laparoscopic compared with vaginal hysterectomy would decrease considerably, without compromising patient safety.

In conclusion, our study demonstrates that, in experienced hands, TLH is associated with less postoperative pain compared to VH. However, because the advantages of TLH and VH are similar apart from postoperative pain and the differences in outcome are small, thus, when deciding the method of hysterectomy between TLH and VH, the skills of the surgeon and the quality of the surgeon's training should be taken into account. In the future, broader prospective studies with larger number of patients are required to compare TLH and VH according to postoperative pain.

Figures and Tables

References

1. Wilcox LS, Koonin LM, Pokras R, Strauss LT, Xia Z, Peterson HB. Hysterectomy in the United States, 1988-1990. Obstet Gynecol. 1994. 83:549–555.

2. Lepine LA, Hillis SD, Marchbanks PA, Koonin LM, Morrow B, Kieke BA, et al. Hysterectomy surveillance: United States, 1980-1993. MMWR CDC Surveill Summ. 1997. 46:1–15.

3. Wu JM, Wechter ME, Geller EJ, Nguyen TV, Visco AG. Hysterectomy rates in the United States, 2003. Obstet Gynecol. 2007. 110:1091–1095.

4. Australian Institute of Health and Welfare (AIHW). Australian hospital statistics 2002-03. AIHW cat. no. HSE 32. 2004. Canberra: AIHW.

5. Cosson M, Querleu D, Crepin G. Cosson M, Querleu D, Crepin G, editors. Hysterectomies for benign disorders. Gynecology. 1997. Paris: Williams and Wilkins;160–173.

6. Reich H. Laparoscopic hysterectomy. Surg Laparosc Endosc. 1992. 2:85–88.

7. Vaisbuch E, Goldchmit C, Ofer D, Agmon A, Hagay Z. Laparoscopic hysterectomy versus total abdominal hysterectomy: a comparative study. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 2006. 126:234–238.

8. Nieboer TE, Johnson N, Lethaby A, Tavender E, Curr E, Garry R, et al. Surgical approach to hysterectomy for benign gynaecological disease. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2009. (3):CD003677.

9. Ribeiro SC, Ribeiro RM, Santos NC, Pinotti JA. A randomized study of total abdominal, vaginal and laparoscopic hysterectomy. Int J Gynaecol Obstet. 2003. 83:37–43.

10. Soriano D, Goldstein A, Lecuru F, Daraï E. Recovery from vaginal hysterectomy compared with laparoscopy-assisted vaginal hysterectomy: a prospective, randomized, multicenter study. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand. 2001. 80:337–341.

11. Rosenquist RW, Rosenberg J. United States Veterans Administration. Postoperative pain guidelines. Reg Anesth Pain Med. 2003. 28:279–288.

12. Bonica JJ. The need of a taxonomy. Pain. 1979. 6:247–248.

13. Kovac SR. Guidelines to determine the route of hysterectomy. Obstet Gynecol. 1995. 85:18–23.

14. Sheth SS. Vaginal hysterectomy. Best Pract Res Clin Obstet Gynaecol. 2005. 19:307–332.

15. Garry R, Fountain J, Mason S, Hawe J, Napp V, Abbott J, et al. The eVALuate study: two parallel randomised trials, one comparing laparoscopic with abdominal hysterectomy, the other comparing laparoscopic with vaginal hysterectomy. BMJ. 2004. 328:129.

16. Summitt RL Jr, Stovall TG, Lipscomb GH, Ling FW. Randomized comparison of laparoscopy-assisted vaginal hysterectomy with standard vaginal hysterectomy in an outpatient setting. Obstet Gynecol. 1992. 80:895–901.

17. Nascimento MC, Kelley A, Martitsch C, Weidner I, Obermair A. Postoperative analgesic requirements - total laparoscopic hysterectomy versus vaginal hysterectomy. Aust N Z J Obstet Gynaecol. 2005. 45:140–143.

18. Doğanay M, Yildiz Y, Tonguc E, Var T, Karayalcin R, Eryilmaz OG, et al. Abdominal, vaginal and total laparoscopic hysterectomy: perioperative morbidity. Arch Gynecol Obstet. 2011. 284:385–389.

19. Johnson N, Barlow D, Lethaby A, Tavender E, Curr L, Garry R. Methods of hysterectomy: systematic review and meta-analysis of randomised controlled trials. BMJ. 2005. 330:1478.

20. Candiani M, Izzo S, Bulfoni A, Riparini J, Ronzoni S, Marconi A. Laparoscopic vs vaginal hysterectomy for benign pathology. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2009. 200:368.e1–368.e7.

21. Schindlbeck C, Klauser K, Dian D, Janni W, Friese K. Comparison of total laparoscopic, vaginal and abdominal hysterectomy. Arch Gynecol Obstet. 2008. 277:331–337.

22. Silva-Filho AL, Rodrigues AM, Vale de Castro Monteiro M, da Rosa DG, Pereira e Silva YM, Werneck RA, et al. Randomized study of bipolar vessel sealing system versus conventional suture ligature for vaginal hysterectomy. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 2009. 146:200–203.

23. Hefni MA, Bhaumik J, El-Toukhy T, Kho P, Wong I, Abdel-Razik T, et al. Safety and efficacy of using the LigaSure vessel sealing system for securing the pedicles in vaginal hysterectomy: randomised controlled trial. BJOG. 2005. 112:329–333.

24. Sculpher M, Manca A, Abbott J, Fountain J, Mason S, Garry R. Cost effectiveness analysis of laparoscopic hysterectomy compared with standard hysterectomy: results from a randomised trial. BMJ. 2004. 328:134.

PDF

PDF ePub

ePub Citation

Citation Print

Print

XML Download

XML Download