Abstract

Premenstrual dysphoric disorder (PMDD) is a common condition that temporarily, but repetitively affects patient's global function. Patients and physicians alike are often uncertain whether prescription medication for PMDD is sufficiently effective. The primary objective of this analysis is signal detection in efficacy of pharmacological treatments in PMDD. Secondary objective is to review which symptoms are likely to respond to which medications. The review included otherwise healthy women with clinician confirmed diagnosis of PMDD who participated in phase 3 clinical trials for the treatment of PMDD. Twelve pair-wise comparisons of drug and placebo for 2,420 patients with PMDD were performed. Oral contraceptives and selective serotonin receptor inhibitor were effective in alleviating symptoms of PMDD compared to placebo. Both Intermittent and continuous administration were more effective than placebo. This meta-analysis provides a signal that pharmacological treatment of PMDD is effective.

Up to 80% of women experience physical and emotional changes that are related to their menstrual cycle. Among the nearly 150 reported cyclically recurrent emotional and somatic symptoms, the most common include irritability, fatigue, depression or mood swings, breast tenderness, bloating, and food cravings [1-3]. Approximately 3%-8% of reproductive-age women experience mood, behavioral and/or physical symptoms during the final week of their menstrual cycle that are severe enough to meet the criteria for premenstrual dysphoric disorder (PMDD) [4-6].

PMDD is thought to result from the complex interaction among ovarian steroid production, endogenous opioid peptides, central neurotransmitters, prostaglandins, and peripheral autonomic and endocrine systems [7-9]. Of the wide range of medications available for this treatment approach, the most commonly used agents are oral contraceptives and antidepressants.

As a clinician faced with patients who complain of premenstrual symptoms, it is difficult to predict which symptoms will benefit from treatment with which drug. In some cases, it is puzzling on the part of both patients and physicians whether premenstrual distress requires medical treatment at all. Often, patients read about alternative remedies advertised in beauty magazines, newspapers, television ads, the internet, and seek advice from friends and family. There is overwhelming amount of information on which underwear to wear, which foods to eat and avoid, special herbs, drinks, even lucky charms. In the midst of all the available remedies, one wonders what role medications can have in the competition.

This paper aims to summarize and help readers understand the evidence, and ultimately help physicians make practical decisions about pharmacotherapy for PMDD. The primary objective of this review is to search for signals regarding the following questions: Does PMDD benefit from pharmacological treatment? If so, how much benefit can be expected? Secondary objective is to review which symptoms are likely to respond to which medications.

The review will examine otherwise healthy women with clinician confirmed diagnosis of PMDD according to Diagnostic and Statistical Manual Fourth Edition (DSM-IV) who participated in PMDD phase 3 clinical trials. The reason for selecting only phase 3 studies to compare is mainly because the primary endpoints in PMDD rely mainly on patient's subjective experience. Unless the studies are well controlled and adequately blinded, there is potentially high risk of bias.

The interventions of interest are prescription pharmacological treatments for PMDD. Variations in intervention including dosage, frequency, timing and duration of treatment will be included. Trials including combination with another intervention for PMDD will be excluded. The interventions are to be compared with inactive control intervention (i.e., placebo).

Condition search for "premenstrual dysphoric disorder" was performed on http://www.clinicalstudyresults.org. The search yielded ten phase 3 clinical trials. Six out of the ten trials from the initial search output had sufficient information to be included in this analysis. Four studies did not have published trial results. Five trials had sufficient information in the registry to be included in this review. One trial did not contain sufficient information in the registry, but was linked to a publication [10] which provided the necessary information.

Additional PubMed search for ("premenstrual dysphoric disorder" [All Fields] OR PMDD [All Fields] AND Clinical Trial, Phase III [PT]) yielded no result.

A total of six trials met the pre-defined patient group, intervention, comparisons, outcomes (PICO) criteria and had sufficient information for analyses. One trial was performed using drospirenone (DR) and ethinyl-estradiol (EE) as the active treatment. The other five trials used paroxetine, a serotonergic antidepressant.

The study using DR and EE combination as the active drug was performed by Bayer (study 91001) [11]. This was a double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled, crossover multicenter trial performed in the US. The study evaluated the efficacy of a monophasic oral contraceptive preparation containing DR 3 mg and EE 20 µg (as beta-cyclodextrin clathrate) in the treatment of PMDD.

Otherwise healthy women of reproductive age with a diagnosis of PMDD were enrolled. Sixty-four patients were randomized to either active drug or placebo for three cycles and then after a washout period of one cycle, switched to the other group (crossover). Each subject was observed over three menstrual cycles each on drug and placebo. In the active drug group, subjects received the active tablet for 24 days followed by 4 inert tablets.

The primary efficacy measurement was the Daily Record of Severity of Problems (DRSP) score. The measurement used in this meta-analysis is the mean DRSP score over 3 cycles. Two pair-wise drugs vs. placebo comparisons were made from each of the two stages (pre/post crossover).

The five trials using paroxetine were performed by GlaxoSmithKline: 29060/677 [12], 29060/688 [13], 29060/689 [14], 29060/711 [15], 29060/717 [16].

Study 677, 688, and 689 [12-14] had identical study designs: double-blind, placebo-controlled, three-arm fixed-dose studies of two doses of (12.5 mg/day and 25 mg/day) controlled release (CR) paroxetine and placebo continuous treatment. The subjects in these studies were outpatient women of 18 to 45 years of age, with regular menstrual cycles (i.e., duration between 22 and 35 days), with diagnosis of PMDD according to DSM-IV (criteria A-C fulfilled at the screening visit and criterion D in two consecutive reference cycles) and had PMDD in at least 9 out of 12 menstrual cycles during the past year. After screening for historical diagnosis of PMDD, the subjects filled out daily symptom records for two to three consecutive menstrual cycles for confirmatory clinical diagnosis.

Primary efficacy measurement was the change from baseline in mean luteal phase mood score on a visual analogue scale (VAS) following treatment over three menstrual cycles, which is the measure used in this meta-analysis. For handling of missing data, these studies used the intention-to-treat (ITT) analyses with last observation carried forward (LOCF). Two pair-wise comparisons are made from each study: paroxetine CR 12.5 mg vs. placebo, and paroxetine CR 25 mg vs. placebo.

Study 677 [12] was a multicenter trial in the US; the number of analyzable subjects on paroxetine CR 12.5 mg, 25 mg and placebo were 93, 110, and 105, respectively. Study 688 was conducted in seven European countries and South Africa; the number of analyzable subjects on paroxetine CR 12.5 mg, 25 mg and placebo were 116, 122, and 116, respectively. Study 689 was conducted in the US and Canada; the number of analyzable subjects on paroxetine CR 12.5 mg, 25 mg and placebo were 114, 120, and 124, respectively.

Study 711 [15] was a three-month extension study following studies 677, 688, 689, in which completers from these trials were continued on their randomized treatment groups with the same primary efficacy measure.

Study 717 [16] examined intermittent dosing with paroxetine CR groups (12.5 mg, 25 mg) receiving active drug only during the luteal phases. The inclusion criteria, primary efficacy measurement were same as the other paroxetine studies above.

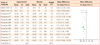

Twelve pair-wise comparisons of drug and placebo for 2,420 patients with PMDD were performed. Efficacy meta-analysis is presented in Fig. 1.

Various treatments are available for treatment of PMDD, including vitamins, mineral, and herbal treatments. Pharmacotherapy for PMDD is based on two main modes of action, cycle inhibition through oral contraceptives (OCP) and neurotransmitter modulation through selective serotonin receptor inhibitors (SSRIs). This meta-analysis included both OCP and SSRI.

Risk of bias is minimal as all trials were phase 3 industry controlled studies that can be assumed to have adequate randomization, blinding, and regulatory oversight for data quality. Selected reporting bias may have been introduced due to the omitted studies lacking sufficient information in their study reports. Additionally, specific inclusion and exclusion criteria and methods of outcome measurements including timing are likely to have been optimized to confer superiority of the drug by the company conducting the clinical trial.

Trials with controlled-release paroxetine, an SSRI, focused on measuring the change in mood. On the other hand, DR/EE is an oral contraceptive with spironolactone-like progestin with antiandrogenic and antimineralocorticoid activity, and its reports use a composite measurement for PMDD. Both drugs were effective in comparison with placebo. However, with different outcome measurements, the superiority of drugs cannot be discussed. Both intermittent and continuous administration seems to be more effective than placebo. Timing of drug administration needs further studies as well as treatment duration, long-term efficacy and safety.

The DR/EE study utilized mean DRSP score as the main outcome measure to be compared. It is uncertain how drop-out patients were treated in the analyses. The controlled-release paroxetine studies used ITT analyses with LOCF, which incorporates to some extent safety and tolerability information as patients dropping out due to clinically intolerable adverse events will be captured essentially as having had no efficacy benefit beyond the last assessment.

From Fig. 1, it appears that lower dose (12.5 mg) of paroxetine CR may be more effective in PMDD than higher dose (25 mg). This is less likely due to better tolerability of the lower dose, since patients were examined over several menstrual cycles. Of note is that paroxetine has a black-box warning for teratogenicity. According to the prescribing information, cardiovascular malformations (especially ventricular and atrial septal defects), and spontaneous abortion risk increases [17]. Special caution should be taken with patient education and contraception since this is reproductive population.

This meta-analysis only provides a signal that prescription pharmacotherapy of PMDD is effective. When PMDD presents with prominent mood symptoms, there is more specific positive evidence towards paroxetine. However, when physical symptoms are more prominent, DR/EE seems to have more specific evidence. Ultimately, selecting the optimal medication for each individual patient should be a clinical decision.

Figures and Tables

Fig. 1

Drospirenone (DR)/ethinyl-estradiol (EE). SD, standard deviation; CI, confidence interval. aStudy stage 1; bStudy stage 2; cParoxetine controlled release 12.5 mg (otherwise 25 mg).

Heterogeneity: Chiz = 1069.63, df = 11 (P <0.00001); Iz = 99%.

Test for overall effect: Z = 151.80 (P <0.00001).

References

1. Logue CM, Moos RH. Perimenstrual symptoms: prevalence and risk factors. Psychosom Med. 1986. 48:388–414.

2. Ramcharan S, Love EJ, Fick GH, Goldfien A. The epidemiology of premenstrual symptoms in a population-based sample of 2650 urban women: attributable risk and risk factors. J Clin Epidemiol. 1992. 45:377–392.

3. Sveinsdóttir H, Bäckström T, Backstrom T. Menstrual cycle symptom variation in a community sample of women using and not using oral contraceptives. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand. 2000. 79:757–764.

4. American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders (DSM-IV-TR). 2000. 4th ed. Arlington, (VA): American Psychiatric Association.

5. Wittchen HU, Becker E, Lieb R, Krause P. Prevalence, incidence and stability of premenstrual dysphoric disorder in the community. Psychol Med. 2002. 32:119–132.

6. Halbreich U, Borenstein J, Pearlstein T, Kahn LS. The prevalence, impairment, impact, and burden of premenstrual dysphoric disorder (PMS/PMDD). Psychoneuroendocrinology. 2003. 28:Suppl 3. 1–23.

7. Freeman EW. Premenstrual syndrome: current perspectives on treatment and etiology. Curr Opin Obstet Gynecol. 1997. 9:147–153.

8. Halbreich U. Premenstrual syndromes: closing the 20th century chapters. Curr Opin Obstet Gynecol. 1999. 11:265–270.

9. Mortola JF. Premenstrual syndrome. Trends Endocrinol Metab. 1996. 7:184–189.

10. Pearlstein TB, Bachmann GA, Zacur HA, Yonkers KA. Treatment of premenstrual dysphoric disorder with a new drospirenone-containing oral contraceptive formulation. Contraception. 2005. 72:414–421.

11. Clinical trials 91001 [Internet]. Bayer Healthcare. cited 2012 Jan 14. Berlin (DE): Bayer;Available from: http://www.bayerhealthcare.com/scripts/pages/en/research_development/clinical_trials/trial_finder/trialfinder_detail.php?trialid=91001&search=91001&product=&overall_status=&country=&phase=&condition=&results=0&trials=0&btnSubmit=submit&num=30&show=1.

12. Clinical study 29060/677 [Internet]. GlaxoSmithKline. 2012. cited 2012 Jan 14. Middlesex (UK): GlaxoSmithKline;Available from: http://www.gsk-clinicalstudyregister.com/result_detail.jsp?protocolId=29060%2f677&studyId=3742A8A5-2C3C-4A40-B9B5-7975DF70CF53&compound=paroxetine.

13. Clinical study 29060/688 [Internet]. GlaxoSmithKline. 2012. cited 2012 Jan 14. Middlesex (UK): GlaxoSmithKline;Available from: http://www.gsk-clinicalstudyregister.com/result_detail.jsp;jsessionid=CC6457E95B10471DFE84DE6FF7B160D3?protocolId=29060%2f688&studyId=4EAE38F8-954D-453B-BA8C-32CA4FFAD277&compound=paroxetine.

14. Clinical study 29060/689 [Internet]. GlaxoSmithKline. 2012. cited 2012 Jan 14. Middlesex (UK): GlaxoSmithKline;Available from: http://www.gsk-clinicalstudyregister.com/result_detail.jsp;jsessionid=CC6457E95B10471DFE84DE6FF7B160D3?protocolId=29060%2f689&studyId=6F9A5C75-99C3-4F11-AED7-A122263D1746&compound=paroxetine.

15. Clinical study 29060/711 [Internet]. GlaxoSmithKline. 2012. cited 2012 Jan 14. Middlesex (UK): GlaxoSmithKline;Available from: http://www.gsk-clinicalstudyregister.com/result_detail.jsp;jsessionid=CC6457E95B10471DFE84DE6FF7B160D3?protocolId=29060%2f711&studyId=4A384A1A-46F7-4E8B-915B-4B324BB64491&compound=paroxetine.

16. Clinical study 29060/717 [Internet]. GlaxoSmithKline. 2012. cited 2012 Jan 14. Middlesex (UK): GlaxoSmithKline;Available from: http://www.gsk-clinicalstudyregister.com/result_detail.jsp;jsessionid=CC6457E95B10471DFE84DE6FF7B160D3?protocolId=29060%2f717&studyId=CA9A3538-05F2-43D8-A1E2-342281DDD178&compound=paroxetine.

17. PAXIL (paroxetine hydrochloride) tablets and oral suspension [Internet]. GlaxoSmithKline. 2012. cited 2012 Jan 14. Research Triangle Park (NC): GlaxoSmithKline;Available from: http://us.gsk.com/products/assets/us_paxil.pdf.

PDF

PDF ePub

ePub Citation

Citation Print

Print

XML Download

XML Download