Chondrosarcoma is the second most common primary tumor of the bone in both humans and dogs, and it accounts for approximately 5% to 10% of all canine primary bone tumors [9]. Primary chondrosarcomas in dogs have reportedly been found in the appendicular skeleton, mammary gland, digit, tongue, kidney, abdominal wall, omentum, trachea, synovium, subcutaneous tissue, larynx, lung, pericardium, right atrium, mitral valve, aorta and penile urethra [2,8,9]. However, chondrosarcoma on the skull is rare, representing approximately 0.1% of all head and neck neoplasms in humans [3]. This report describes the clinical presentation and diagnostic investigation, which involved x-ray, computed tomography (CT, Pratico; Hitachi Medico, Japan), and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI, Aperto Inspire; Hitachi Medico, Japan) examinations, of a dog with chondrosarcoma in its skull.

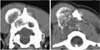

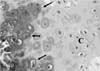

A 5-year-old, neutered, female golden retriever was presented to the Yamaguchi University Veterinary Medical Hospital with a mass on the head. The owner reported that the mass was found one month previously and it had slowly enlarged. However, the dog appeared otherwise well, and it had no past trauma or medical history except for otitis externa. A physical examination revealed a hard mass, which was fixed to the left caudal part of the head, and the skin overlying the lesion was normal. There were no significant abnormalities on the neurological and blood examinations. Radiographic examination of the head revealed a lytic lesion with endosteal scalloping on the parietal bone that extended to the occipital bone (Fig. 1A) and there was faint calcific opacity in the overlying mass (Fig. 1B). A CT scan (Fig. 2) revealed a large mass involving bone destruction, prominent matrix mineralization and low-attenuation areas. Transverse T1-weighted MRI (Fig. 3A) showed a slightly low-signal intensity area on the brain and adjacent lesion, and the same area showed high-signal intensity on the T2-weighted images (Fig. 3B & D). The adjacent brain parenchyma was compressed by the mass (Fig. 3D). The mass had mild marginal enhancement on a contrast-enhanced T1-weighted image, and it was separated from the brain parenchyma (Fig. 3C). Biopsy of the lesion was performed, and the mass was histopathologically diagnosed as chondrosarcoma (Fig. 4). The owner was unwilling to permit palliative surgery.

Chondrosarcoma is a malignant tumor involving the cells that produce a cartilage matrix [7]. Although chondrosarcomas most commonly arise from either the cartilaginous structures or the bones derived from chondroid precursors, chondrosarcomas may also arise in those areas where cartilage is not normally found. The chondrosarcomas developing in soft tissue presumably arise from cartilaginous differentiation of primitive mesenchymal cells [3].

In a retrospective study of 97 dogs with chondrosarcomas [8], those dogs with a mean age of 8.7 years (range: 1 to 15 years) and medium-to-large breed dogs (mean weight: 28 kg) were most commonly affected. Golden retrievers had a 3.12 times greater risk of developing chondrosarcoma than any other breed. The nasal cavity was the most common site (28.8%), followed by the ribs (17.5%), appendicular skeleton (17.5%), extraskeletal sites (13%), and facial bones (9%). Chondrosarcomas of the facial bones were located in the mandibule, maxilla and orbit [8]. Human chondrosarcoma commonly arises in the appendicular skeleton and ribs. The most common sites in the head and neck have been variably reported as the jaw bones, paranasal sinuses, nasal cavity, the maxilla and cervical vertebrae [3]. There are fewer reports of chondrosarcomas on the head, including the cranium, in comparison with other lesions, in both human and veterinary medicine [3-5,8].

Multilobular osteochondrosarcoma (MLO) is an uncommon tumor that generally arises in the skull of dogs [5,9]. MLO has similar radiographic characteristics and MRI appearance as chondrosarcomas have and it histologically contains a chondroid and osteoid matrix. On the histopathological examination of this case, a chondroid matrix was dominant, and this led to the diagnosis of chondrosarcoma. However, MLO could not be ruled out because the histopathological samples were only collected at several points via needle punch biopsy.

The radiographic (Fig. 1) and CT (Fig. 2) examinations showed soft tissue calcification and bone lysis with endosteal scalloping. On MRI examination (Fig. 3), a T1-weighted image showed a low-signal intensity area on the brain and adjacent muscle, and a T2-weighted image revealed marked high-signal intensity, which was similar to that of cerebrospinal fluid. Hyaline cartilage neoplasms typically grow with a lobular architecture. This growth pattern frequently causes lobular, deep, endosteal scalloping that may result in focal areas of cortical penetration and associated extension into the soft-tissue. Non-mineralized regions have a translucent appearance, reflecting the high water content of hyaline cartilage, and particularly in low-grade lesions. The lobular architecture typical of all hyaline cartilage neoplasms, in most cases, can best be seen at the lesion margin. The non-mineralized components of chondrosarcoma have high-signal intensity on T2-weighted MRI, which is again a reflection of the high water content of hyaline cartilage [7,10].

The dog had a mass on the head that had invaded the parietal and occipital bones, and this compressed the right occipital lobe of the cerebrum and the cerebellum. However, the mass was round and well defined from the brain parenchyma. Despite the large intracranial mass lesion, the dog did not show any neurological disorders and the owner did not notice any changes in its daily routine. The most frequently reported clinical sign in dogs with chondrosarcoma involving the facial bones (included all the bones of the skull not associated with the nasal cavity or paranasal sinuses) is a mass or swelling over the affected area [3,5,8,9]. Canine chondrosarcomas tend to grow slowly and they have limited metastatic potential, with the reported metastatic rates ranging from 0 to 20.5% [2]. Because of its slow growth, the brain parenchyma may become accustomed to the compression caused by the mass.

In this case, the owner was unwilling to have palliative surgery performed. The location of tumor and the histologic grade are generally prognostically related and surgical excision is the primary treatment [3,8]. There was a significant difference in survival time between the dogs with appendicular chondrosarcoma that were treated with amputation and those dogs treated by local excision [8]. Investigators have identified that chondrosarcoma is not a radio-responsive tumor and as a result, radiotherapy is not useful as a primary modality or as an adjunct to surgery [3]. The median survival times of dogs suffering with nasal chondrosarcoma and treated with rhinotomy did not differ significantly from those dogs for which rhinotomy was followed by radiotherapy [8].

Since the expansion of MRI and CT into the veterinary field, the management of tumors has been a formidable challenge for clinicians. However, many patients with extensive disease, and especially those displaying slow progression of tumors, show clinical signs only in the late stages of the disease when gross total resection of the tumor tissues is difficult at best. Because the skull is a complex structure with many overlapping shadows, it may be difficult to discern the pattern of bone destruction and the presence of matrix by using only X-ray. It is recommended that CT and MRI be performed when a lesion is suspected or discovered on the head, even where there are no signs of neurological disorder. Both CT and MRI may be necessary for thoroughly evaluating the extent of tumor [1,4,6].

In this case, CT was useful for detecting the matrix mineralization, and T2-weighted MRI allowed visualization of the nonmineralized components of chondrosarcoma that had a high-signal intensity, which reflected the high water content of hyaline cartilage.

PDF

PDF ePub

ePub Citation

Citation Print

Print

XML Download

XML Download