Introduction

The kidneys are paired organs that function in excretion, metabolism, secretion, and hormonal or electrolyte regulation (including the hormones renin and erythropoietin), and are susceptible to diseases of the glomeruli, tubules, interstitium, and vasculature [7]. Nephrotoxins, infections, urinary crystals and calculi, neoplasms, hypoxia, and genetic/familial determinants can result in renal diseases; the resulting conditions include glomerulonephritis, developmental abnormalities; and tubule, interstitial, and renal pelvis disorders.

Glomerulonephritis (GN) is the degeneration or inflammation of renal glomeruli characterized by proliferative changes in the glomerular basement membrane with hyaline degeneration [7]. Glomerular diseases are a common cause of chronic renal failure in human patients [5]. However, chronic stage canine renal disease has been traditionally classified as chronic interstitial nephritis [10], and the incidence of canine GN is reportedly low [9]. Previous studies in dogs have been able to classify canine renal diseases according to the World Health Organization (WHO) collaborator study data for the histological classification of renal diseases [1,9,18]. However, the WHO criteria might not be appropriate for dogs due to differences in disease etiology or progression.

Renal tubules and interstitial tissue can undergo degeneration secondary to glomerular damage. Therefore, only primary degenerative and inflammatory diseases of the renal tubules and interstitium without glomerular changes are classified as diseases of the renal tubules and interstitium [5]. Tubular and interstitial diseases are secondary to tubular injuries (ischemic or toxic) or inflammatory reactions of the tubules and interstitium [5]. The macroscopic lesions of tubular or tubulointerstitial diseases include swollen kidneys and color changes secondary to uric acid deposition. Infiltration of inflammatory cells into the renal medulla and tubular degeneration are microscopically detectable in the acute phases of disease. Primary tubulointerstitial disease, interstitial nephritis, and pyelonephritis could be included in this category.

Diseases of the renal vasculature include renal arterial sclerosis and thrombotic microangiopathies with pathological changes in the kidney that include infarction, hyperemia, and hemorrhage. Other renal diseases include ones associated with urinary obstruction, renal tumors, end-stage renal disease (ESRD), renal abscess, and renal cysts. Severe and prolonged kidney disease results in a similar end point of chronic renal failure. Criteria used for ESRD diagnosis are the coexistence of glomerular degeneration and severe interstitial fibrosis with tubular atrophy, and biochemical evidence of uremia or renal calcification [20]. ESRD cases demonstrate very similar histopathological results as end-point chronic renal disease. This study evaluated cases of canine renal disease in Korea within a six-year period and examined the histopathological findings associated with each diagnosis. The distribution of canine renal disease in this study was examined and compared to studies in humans [4] or previous canine GN studies from other countries [1,9,18].

Materials and Methods

Study population

Biopsy or necropsy specimens (n = 1,825) were submitted to the Department of Veterinary Pathology from 2003 to 2008; 1,726 specimens (94.6%) were canine tissue samples. The total of 70 canine renal tissue samples was included in this study.

Histopathologic examination

All samples were fixed in 10% neutral buffered formalin and were subsequently embedded in paraffin. Diagnosis and histological examination of the tissue samples were conducted using hematoxylin and eosin staining and light microscopy. Histopathology diagnoses were determined independently by two pathologists with no prior knowledge of the clinical cases. The pathologists determined that secondary classification of the cases according to veterinary pathology histopathological criteria was more appropriate for canine renal diseases than WHO criteria. Canine focal segmental glomerulosclerosis was the exception and could be categorized using the WHO criteria. Samples with lesions characterized by partial glomerular sclerosis of a portion of the capillary tuft were classified as cases of focal segmental glomerulosclerosis.

Some ESRD cases were strongly suggestive of chronic stages of GN. However, samples were classified as ESRD (1) if glomerulitis and severe interstitial fibrosis with tubular atrophy were both present without identification of the etiology, and (2) if there was biochemical evidence of uremia or renal calcification as previous study [20]. Samples from chronic renal failure cases associated with melamine toxicity demonstrated ESRD lesions with melamine crystals. In these cases, the diagnosis was urolithiasis if crystals were present.

Immunohistochemistry and immunofluorescence

Immunohistochemistry (IHC) and immunofluorescence (IF) was performed to further characterize the histopathology in some cases. Briefly, sections were deparaffinized and treated with a 3% hydrogen peroxide (H2O2) solution for 20 min. Antigens were retrieved by boiling the tissue sections in Tris-EDTA buffer (pH 9) for 10 min in a microwave oven. The sections were incubated with an anti-human IgA mouse monoclonal antibody (1 : 16 dilution; Santa Cruz Biotechnology, USA) at 4℃ overnight or with a fluorescein isothiocyanate-conjugated anti-dog C3 mouse monoclonal antibody (1 : 200 dilution; Bethyl Laboratories, USA) at room temperature for 2 h. Primary antibody binding was visualized using a EnVision horseradish peroxidase-based kit (Dako Cytomation, USA), and samples were counterstained with Harris' hematoxylin. Positive controls included samples from cases of canine inflammatory bowel disease and normal splenic tissues.

Special stains

Masson's trichrome, periodic acid Schiff (PAS), and Warthin starry silver stains were used in specific cases according to standard histochemical methods [13]. Masson's trichrome staining was performed to estimate renal fibrosis in ESRD and renal interstitial fibrosis cases. PAS staining was performed to assess the glomerular basement membranes of canine glomerulonephritis cases. Warthin starry silver stains were applied to the cases of chronic interstital nephritis or ESRD to exclude leptospirosis of kidney. Digital images were acquired with a microscope (BX41; Olympus, Japan) equipped with a digital camera and digital image transfer software (Leica Microsystems, Switzerland).

Results

A total of 70 canine renal tissue samples (4.1% of the total canine cases) were collected during the study. Samples from both male (n = 27) and female (n = 39) animals were included, and four samples came from unidentified sexes. The age of all canine patients (mean ± SD, here and hereafter) was 5.5 ± 4.2 years (range, 2 months to 16 years). The highest numbers of renal cases were identified in 2003 and 2004, and the greatest number of renal tissues was submitted in 2003 (n = 40).

Diseases of the glomerulus

There were 16 GN cases, and seven different types of GN were identified (Table 1). Acute proliferative GN was most commonly diagnosed, followed by membranous and membranoproliferative GN. The age of the GN patients was not associated with histological classification.

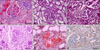

The glomeruli of acute proliferative GN cases were congested or edematous. Glomeruli were highly cellular due to increased numbers of endothelial and/or mesangial cells compared to normal kidney (Fig. 1A). Membranous GN cases showed irregularly thickened histopathologic changes in the glomerular basement membrane and such changes were highlighted with PAS staining (Fig. 1B). The amount of blood in the glomeruli was decreased in membranous GN cases, and glomeruli were not congested, as was observed in acute proliferative GN. Both proliferative and membranous changes were observed in membranoproliferative GN (Fig. 1C); these cases showed irregularly thickened glomerular basement membranes.

Focal segmental glomerulosclerosis and renal amyloidosis was observed in 2.9% of the total cases. Focal segmental glomerulosclerosis cases were characterized by sclerosis of some glomeruli with involvement of a portion of the capillary tuft (Fig. 1D). Renal amyloidosis was easily diagnosed with Congo Red staining (Fig. 1E).

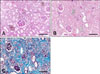

A single case of IgA nephropathy was diagnosed by IgA antibody IHC (Fig. 1F). Weak and diffuse labeling was evident. The patient was a one-year old female Schnauzer and the kidney specimen was obtained by necropsy. Three cases showed diffuse, intense granular deposits along the basement membrane with IF analysis using the anti-C3 antibody (Fig. 2). The cases included one case each of IgA nephropathy, acute proliferative GN, and membranous GN.

The single case of unclassified glomerulonephropathy had histological characteristics very similar to human hypertensive renal disease and failure (data not shown).

Diseases of the tubulointerstitium

Diseases of the tubulointerstitium (Table 1) consisted of chronic interstitial nephritis (n = 6) and pyelonephritis (n = 1). The mean age of these patients was 11.3 years (range, 5 to 16 years). Prominent interstitial fibrosis and tubular atrophy without severe glomerular changes was characteristic (Fig. 3A). Several cases demonstrated interstitial edema and focal tubular necrosis. Pyelonephritis cases demonstrated purulent exudates in the renal pelvis and necrosis of the medulla with neutrophil infiltration (Fig. 3B); one case had a clinical history of severe cystitis.

Urinary obstruction diseases

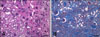

Renal tissue samples (n = 17) from urinary obstruction cases were submitted. Fifteen cases were diagnosed with urolithiasis. Melamine-associated renal failure (MARF) was diagnosed in 14 of these cases, and the remaining case was diagnosed with oxalate nephrosis. Acute MARF (n = 8) was characterized by severe distal tubular necrosis with intratubular crystals and no evidence of significant interstitial fibrosis or inflammation (Fig. 4A). The remaining cases were chronic MARF cases which demonstrated renal intratubular crystals in the distal tubules. Chronic MARF cases had moderate to severe renal interstitial fibrotic changes on histopathology (Figs. 4B and C). Hydronephrosis was identified in two cases.

Renal tumors

Primary renal tumors were identified in five cases. Renal carcinoma types that were observed included papillary (n = 2), tubular (n = 2), and clear cell renal cell (n = 1) carcinomas (Figs. 5A-C). The average age of the carcinoma patients was 5.9 ± 1.8 years (range, 4 to 9 years). A 12-year-old male Maltese had a metastasized spermatocytic seminoma in the kidney.

Other diseases of the kidney

ESRD was evident in 17.1% of all cases (Table 1). These cases demonstrated an extensive area of fibrosis with destruction of proximal tubules, deposition of extracellular matrix, and spaces of immunocyte infiltration (Figs. 6A and B), particularly B- and T-lymphocytes. The male-to-female ratio of patients was 0.6 : 1, and the average age was 7.3 ± 3.0 years.

Renal abscess (n = 2), renal cysts (n = 2), and hypertensive arteriolonephrosclerosis (n = 1) were included in the total case count. Cases in the "others" category (Table 1) included insufficient or inadequate biopsy materials (n = 4), and four cases did not show obvious histopathological changes.

Discussion

This report provides information about the occurrence of canine renal diseases during a 6 year period in Korea. Previous studies reported the clinical data of canine renal diseases [16,17], and there have been a few reports about each histological type of canine renal GN [1,9,18]. However, studies evaluating all canine renal diseases including diseases of the tubulointerstitium, urinary obstruction, tumors, and other diseases have not been frequently performed [1,7,9]. In the present study, GN classification was complicated for ESRD cases that were strongly suggestive of chronic stage GN. Three of the 12 cases included glomerular changes associated with crescentic GN or chronic GN forms. However, glomerular changes characteristic of focal embolic GN cases were not observed.

A previous canine study demonstrated the high prevalence of membranoproliferative and membranous GN cases in the total GN cases of a canine population [1]. Membranoproliferative and diffuse mesangial proliferative GN cases had a high incidence in another canine study [9]. On the other hand, acute proliferative GN cases were diagnosed with greater frequency than membranous or membranoproliferative GN cases in the present study, likely due to different methods of classification and GN component ratios.

A Korean study of human patients demonstrated that 97.8% of total renal cases were GN cases [4], and another Saudi Arabian human study demonstrated that 85.7% of total renal cases were GN cases [11]. This suggests that GN is a significant clinical condition in human nephrology as previously described [5]. On the other hand, a previous canine study from the United Kingdom reported that GN comprised only 52.6% of total canine renal diseases [9]. In the present study, the proportion of canine GN diseases among the total studied renal cases was much lower (22.9%), possibly due to the high rate of urolithiasis (22.9%). Biopsies are not typically performed in urolithiasis cases, and most nephroliths found in North American cases are calcium oxalate or struvite calculi rather than melamine-associated crystals [14]. However, there was a massive outbreak of MARF in Korean dogs due to melamine contamination of dog food in 2003 and 2004 [2,19], resulting in severe MARF-induced clinical symptoms and death. Multiple autopsies confirmed the diagnosis of MARF-associated urolithiasis.

The low incidence of minimal change nephrotic syndrome could also contribute to the low GN incidence. In human studies, minimal change nephrotic syndrome (24.2%) was the most frequently diagnosed condition [4]. In this study, four renal tissue samples did not show distinct histopthological changes and were classified as "others". The cases could have been diagnosed as minimal change nephrotic syndrome if biochemical evidence or tissue samples for electron microscopy were available. Although the proportion of canine GN was remarkably lower than that of humans, the component ratio of each histological type of GN was similar to that of human studies except for the low proportion of minimal change nephrotic syndrome and IgA nephropathy [4,6,15].

Tubulointerstitial nephritis or pyelonephritis can result from infectious (bacteria, viruses, parasites) or toxic (drugs, heavy metals) insults [5]. Tubulointerstitial nephritis and pyelonephritis were identified in 8.6% of all included cases in the present study; this was relatively high compared to studies in humans. Pyelonephritis cases had a clinical history of severe cystitis, and could be secondary to ascending infection with Escherichia coli, Proteus spp., or Enterobacter spp. bacteria.

Human renal cell carcinomas represent about 1~3% of all visceral cancers [5], and the reported incidence among dogs is significantly lower at 1.5 cases per 100,000 [12]. The incidence of canine renal cell carcinoma might be higher because five cases of canine renal cell carcinoma were confirmed among the total 1,753 canine cases in this study. A previous study reported that the majority of primary renal tumors are tubular in nature, and clear cell tumor types were reported as being rare in dogs [3]. The small sample size in the present study did not allow for an examination of tumor incidence in this population, but one case of clear cell type renal cell carcinoma was included.

Direct etiologies are not usually identified and early signs of canine renal disease, including abdominal pain or abnormal urination at appropriate times, are not usually recognized. ESRD in humans represents 0.5~3.4% of all renal diseases [4,8]. Canine ESRD was identified at a rate of 17.1% in the present study, and was the most frequent cause of renal biopsies or necropsies. Clinical renal disease in dogs is usually identified at the late stages of disease since pet owners may incidentally miss early clinical symptoms.

In conclusion, several similarities and differences between canine and human renal disease were identified in the present study. The prevalence of canine GN was lower than human GN rates reported in previous studies. However, the component ratio of histological classification of canine GN was similar to human GN. Unlike human ESRD, canine ESRD was one of the top causes of renal biopsy or necropsy due to clinical symptoms of disease progression. In addition, the massive outbreak of MARF in Korean dogs in 2003 and 2004 resulted in unusually high urolithiasis rates. The incidence of canine renal cell carcinoma in this study was higher than previously reported values. It is essential to document the prevalence and distribution of various renal diseases to allow for additional diagnostic and therapeutic information. Future studies should evaluate larger and more diverse canine populations.

PDF

PDF ePub

ePub Citation

Citation Print

Print

XML Download

XML Download