Abstract

Purpose

G-protein coupled estrogen receptor 1 (GPER) probably play important roles in the progression of breast cancer including endocrine therapeutic resistance. We evaluated GPER in primary breast cancers.

Methods

Immunohistochemistry was used to detect GPER in paraffin-embedded tissues of primary breast cancers from 423 patients and GPER expression was correlated with clinicopathological factors.

Results

GPER was expressed in 63.8% of specimens, coexpressed with estrogen receptor alpha (ERα) in 36.6% of tumors and was positive in 62.5% of the ERα-negative tumors. The expression of GPER had no relationship with the status of ERα, progesterone receptor and HER2. Although the expression of GPER was significantly inversely related with nodal status (p=0.045), no correlation between GPER expression and other clinicopathological variables (age, menstruation status, tumor size, stage, histologic grade, Nottingham Prognostic Index or pathological type) was found.

Estrogens play important roles in a wide range of physiological and pathophysiological processes, including carcinogenesis in estrogen targeted organs. Accordingly, estrogen receptors (ER), as mediator of estrogenic effect, are linked to diverse carcinomas as diagnostic marker and prognostic factor. In this regard, the clinical application of ERα in breast cancers is a successful paradigm. Use of tamoxifen (TAM), an endocrine therapeutic agent targeting ERα, has reduced recurrence and improved survival in patients with different stages of breast cancer [1]. Thus, TAM has been widely accepted as a fundamental adjuvant therapy for breast cancers, and ERα is routinely detected in the clinical setting.

However, the expression of ERα does not completely parallel the response to hormonal therapy. Roughly a quarter of ERα positive breast cancers are insensitive to TAM and a substantial proportion of sensitive patients would develop resistance [1]. The identification of G-protein coupled estrogen receptor 1 (GPER), also referred to as GPR30 belonging to the family of G protein-coupled receptors, provides a potential mechanism for these phenomena, for the following reasons: First, the agents applied in hormone therapy of breast cancers, including TAM and fulvestrant, have been repeatedly described as GPER agonists [2,3]. GPER and its cross-talk with epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR) play a key role in acquired resistance in breast cancer cells (MCF-7) after long-term treatment with TAM [4]. Second, GPER may mediate the cytological proliferation effect of estrogenic substances [5]. Third, GPER promotes cellular migration and mobilization in response to estrogen [5,6]. Last, GPER may contribute to the chemoresistance of cytotoxic agents [7]. Furthermore, GPER is associated with poor survival of endometrial carcinoma and ovarian cancers [8,9]. We hypothesize that GPER plays important roles in breast cancer progression or mammary carcinogenesis. To evaluate GPER in primary breast cancers, we assessed its expression by immunohistochemistry, and correlated GPER expression with clinicopathological variables in 423 cases of breast cancers.

A total of 423 archival paraffin-embedded, formalin-fixed breast tumor tissues were obtained from the Clinical Diagnostic Pathology Center, Chongqing Medical University (Chongqing, China). All patients underwent surgery at the First Affiliated Hospital of Chonqing Medical University during 2006-2009. For all patients, detailed clinicopathological data including pathological diagnoses, results of immunohistochemical studies for ERα, progesterone receptor (PR) and HER2, lymph node status, tumor grade, and tumor size were obtained from hospital records. As routine tests, rabbit monoclonal antibodies of ERα (Clone SP1), PR (Clone SP2), and HER2 (Clone SP3) (Maxim.Bio, FuZhou, China) were used in the immunohistochemistry assay. A minimum of 1% positively stained in nucleus of tumor cells in a specimen was considered positive for ERα and PR, whereas if less than 1% of tumor cells stained, the sample was considered negative. Nottingham Combined Histological Grading system was employed to evaluate the tumor grade. Nuclear grade, tubule formation and mitotic rate were given a score between 1 and 3 and the scores of were added together for a total score. Scores of 3-5, 6-7, and 8-9 were defined as the low (G1), intermediate (G2) and high (G3) grade, respectively. As a well accepted predictor, the Nottingham Prognostic Index (NPI=0.2×S+N+G; S is the size of the index lesion, N is the number of involved lymph nodes and G is tumor grade) was calculated for all patients.

Commercial rabbit anti-GPER polyclonal antibodies (Abcam, Cambridge, UK) were applied for GPER immunohistochemical staining, utilizing streptavidin-peroxidase assay according to the manufacturer's instructions. Briefly, 4 µm thick tissues sections were deparaffinized, heated at 95℃ in 0.1 mol/L sodium citrate (pH 6.0) for antigen retrieval, and the endogenous peroxidase activity was quenched with 3% H2O2. Nonspecific binding sites were blocked by incubating with goat serum. Slides were exposed to primary antibodies at a 1:250 dilution, or to phosphate buffered saline (PBS) as a negative control for 2 hours at 3℃. Sections were incubated in horseradish peroxidase-conjugated goat anti-rabbit IgG for 20 minutes at 37℃ to detect tissue-associated rabbit antibodies. Diaminobenezidine was added as the substrate. Nuclei were counterstained using Mayer's modified hematoxylin. As indicated by Filardo et al. [10], reduction mammoplasty tissue was used as a positive control.

Two observers microscopically evaluated the intensity, extent and distribution of the immunreactive area using a modified semiquantitative scoring system [11]. Scores were applied as follows: A staining proportion score: 0, negative staining in all cells; 1, <1% cells stained; 2, 1-10% cells stained; 3, 11-33% cells stained; 4, 34-66% cells stained; 5, 67-100% cells stained; Staining intensity score: 1, weak stained; 2, moderately stained; 3, strongly stained. Adding the two scores together yielded a maximum score of 8. The final scores were grouped into GPER negative (score 0-4) and positive (score 5-8) categories for statistical analyses to reduce inter-observer differences.

The SPSS version 16.0 for Windows (SPSS Inc., Chicago, USA) was utilized for the statistical analysis. Associations between GPER expression and each clinicopathological determinants were evaluated by the χ2 test, the Fisher's exact test (for nominal variables) or the Kruskal-Wallis test (for ordinary variables). Referring to measurement data, non-paired t-test or ANOVA process was used to test difference between subgroups. Two-tailed p-values of 0.05 or less were considered to be statistically significant.

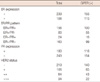

Of the 423 patients included in this study, 54.3% were postmenopausal, their mean age was 51.6±11.5 years (range, 24-94 years). The majority of the cases were invasive ductal carcinomas (90.5%) (Table 1). Distant metastasis was excluded at the time of surgery. We applied the greatest dimension from the ultrasonography or mammography reports to represent the primary tumor size, and the mean tumor size was 26.0±13.6 mm (range, 6-89 mm). Lymph node status was graded considering the number of metastatic reginal lymph nodes, and 40.9% of the cases had a positive in pathological node examination. The disease staging was applied according to the 7th edition of the American Joint Committee on Cancer Staging Manual for Breast Cancer, 41.4% of cancers were in stage II. Most tumors were graded as G2 (67.4%). Approximately a quarter (23.4%) of all patients accepted neoadjuvant chemotherapy. The characteristics of patients and tumors are summarized in Table 1.

GPER was positive in 63.8% of all specimens, which was similar to previous studies [10,13-15], revealing the extensive expression of GPER in primary breast carcinomas. ERα was positive in 56.5% of tumors. GPER and ERα were coexpressed in 36.6% of tumours and concomitantly absent in 16.3% specimens, which was also similar with earlier findings [10].The association between GPER and ERα was not significant (p=0.617), whereas 62.5% of the ERα- specimens were positive for GPER (Table 2), implying the absence of interdependence between the two ERs, consistent with earlier observations [10,13-15]. GPER had no relationship with PR and HER2. In contrast, ERα was positive and inversely associated with PR and HER2 (data not shown), further supporting the notion that GPER is independent of ERα.

GPER+ tumors tended to be larger than GPER- tumors (greatest dimension, 26.5±14.6 mm vs. 25.1±11.4 mm, however, the difference was not significant (p=0.314). The expression of GPER was inversely related to nodal status. GPER+ tumors displayed a significantly lower mean rank of pathological lymph node grade (199.7 vs. 211.2, p=0.045) in Kruskal-Wallis test. No significant difference was found when NPI was compared between GPER+ and GPER- tumors. Moreover, no correlation was found between GPER expression and the other variables analyzed (Table 3).

"Cross-talk" between GPER and ERα has been suggested. We correlated GPER/ERα status to the well known prognostic factors, but no significant differences were found among the four subgroups, excluding that GPER-/ERα- tumors had higher HER2 scores than those of other subgroups (p=0.046) (Table 4).

GPER, which has been widely-accepted as an ER, has been linked to proliferation, migration enhancement [5], mobilization promotion [6], TAM [4], cytotoxic agents [7], resistance in breast cancer cells in vitro. However, only four clinical studies [10,13-15], which included large sample populations have focused on GPER in primary breast cancers. We detected GPER by immunohistochemistry in 241 primary breast cancers to correlate its expression to clinicopathological determinants, resulting in some significant associations [14]. To further evaluate GPER in breast cancers, we expanded the sample size, collected more details of the tumors in the present paper.

In our series, GPER was positive in 63.8% of specimens, regardless of ERα and/or PR status, as well as the histopathological tumor subtype. This proportion is in the range of previous studies, indicating wide distribution for this receptor in breast cancers [10,15]. As aforementioned, there is not complete concordance between the ERα-targeted therapeutic response and its expression [1]. Furthermore, resistance would occur in approximately half of the patients who have taken TAM treatment [1], but the mechanism is not clear. GPER, as an alternative estrogen receptor, may provide a potential interpretation. The interaction between ERs and EGFR has focused much attention on acquired TAM-resistance, whereas GPER can transactivate EGFR in response to TAM, hydroxytamoxifen and fulvestrant [3]. Furthermore, enhanced sensitivity to estradiol (E2) and specific agonist of GPER, G1 (1-[4-(6-bromobenzo[1,3]dioxol-5-yl)-3a,4,5,9b-tetrahydro-3H-cyclopenta[c] quinolin-8-yl]-ethanone), via GPER, has been observed in MCF-7 cells cultured long-term with TAM, resulting in resistance to the inhibitory effect of TAM [4]. Thus, GPER probably plays an important role in the non-response and acquired-resistance to ERα antagonism in patients with breast cancer. In our study, GPER was expressed in 64.9% of patients with ER+ tumors who would presumably take endocrine therapy. For this subpopulation, GPER signalling-blockage should be supplemented with current endocrine therapy. GPER was also respectively detected in 62.5% and 61.9% of ER-, and ER-/PR- cancers, respectively, which would not be included in hormonal therapy. Accordingly, GPER-targeted drugs is possible as an alternative hormonal therapy and would benefit more patients, since a selective GPER antagonist has been identified [16,17].

Filardo et al. [10] was the first to detect GPER in clinical specimens of breast cancer. GPER expression was positively associated with tumor size, HER2 immunohistochemical scores and distant metastasis in their report, suggesting that GPER may be involved in breast cancer progression. In the present series, GPER had no significant influence on the tumor size, consistent with Kuo et al. [13] and our previous report [14] in Chinese but Filardo's [10] observations in Americans. Thus, racial differences may contribute to the discrepancy. Notably, one third (106/321) of the patients in Filardo's series [10] developed metastases, whereas distant metastatic cases were absent in the later reports. This probably underlies the difference. Interestingly, we observed a significant protective effect of GPER on pathological lymph node invasion because GPER+ tumors displayed significant lower mean rank of pathological lymphonode grade (Table 3). None of the early reports showed a significant association between expression of GPER and lymph node invasion [10,13]. There is no more information on this point so far. Thus, a confirmative investigation is needed. For post-operative breast cancers, NPI is the best-documented prognostic index combining tumor size, nodal status and histological grade. ERα had a significant (p=0.048), negative impact on tumor NPI. In contrast, GPER manifested no influence on NPI in our series which was consistent with recent reports showing that GPER has no impact on long-term outcomes of patients with breast cancer [13,15]. The correlation between GPER and HER2 expression is controversial. In contrast to observation by Filardo et al. [10], no significant association between GPER and HER2 expression was found in Kuo's [13], Arias-Pulido's [15], and our investigation (Table 2). Although GPER functionally transactivate EGFR in response to E2, it is worth noting that HER2 is not EGFR and a functional relationship between HER2 and GPER is not implied. GPER showed no relationship with additional prognostic factors either. Thus, GPER may not be an independent prognostic factor. Nevertheless, long-term follow-up outcomes were absent in the present report, limiting our preliminary conclusion.

Coexpression of ERα and GPER has been linked to a better outcome, whereas a lack of any of them is associated with worse survival in patients with invasive ductal carcinomas [13], and inflammatory breast cancer [15], while GPER has no significant, independent impact on the outcomes of breast cancer patients [13,15]. We correlated the status of both ERs to prognostic factors. Interestingly, GPER-/ER- tumors tended to have a maximum NPI, rank of pathological node grade, stage, and histological grade (Table 4), although the differences were not significant excluding HER2 scores across subgroups (p=0.046). This is a reminder that GPER is merely a collaborator in estrogenic effects [18].The interaction between GPER and ERα has been suggested [18], and the function of GPER may vary with ERs expression type in breast cancer cells [19], although the mechanisms are far from clear. Thus, a more definite classification of ERs molecular phenotype is necessary. Confirming studies and long-term follow-up in different subgroups of tumors is significant.

In contrast to studies in vitro, clinical studies have observed a few evident relationship between GPER and tumor progression or survival in patients with breast cancer. Contrary effects exist between the two signalling pathways triggered by GPER [20], thus, the estrogenic effects may be neutralized. Nevertheless, GPER was expressed in most specimens regardless of the status of ER, PR, and HER2. GPER and ERα exhibited an independent pattern of distribution in primary breast cancers. Thus, more definite classification of ERs molecular phenotype is necessary. In addition, confirming studies and a long-term follow-up are needed to further evaluate GPER in the progression of breast cancers and patients' survival.

Figures and Tables

Figure 1

Immunohistochemical staining (DAB) of G-protein coupled estrogen receptor 1 (GPER) in breast cancers. (A) Positive cytoplastic staining pattern. (B) Negative staining paradigm (immunohistochemical stain, ×200).

Notes

References

1. Early Breast Cancer Trialists' Collaborative Group (EBCTCG). Effects of chemotherapy and hormonal therapy for early breast cancer on recurrence and 15-year survival: an overview of the randomised trials. Lancet. 2005. 365:1687–1717.

2. Prossnitz ER, Sklar LA, Oprea TI, Arterburn JB. GPR30: a novel therapeutic target in estrogen-related disease. Trends Pharmacol Sci. 2008. 29:116–123.

3. Thomas P, Pang Y, Filardo EJ, Dong J. Identity of an estrogen membrane receptor coupled to a G protein in human breast cancer cells. Endocrinology. 2005. 146:624–632.

4. Ignatov A, Ignatov T, Roessner A, Costa SD, Kalinski T. Role of GPR30 in the mechanisms of tamoxifen resistance in breast cancer MCF-7 cells. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2010. 123:87–96.

5. Pandey DP, Lappano R, Albanito L, Madeo A, Maggiolini M, Picard D. Estrogenic GPR30 signalling induces proliferation and migration of breast cancer cells through CTGF. EMBO J. 2009. 28:523–532.

6. Quinn JA, Graeber CT, Frackelton AR Jr, Kim M, Schwarzbauer JE, Filardo EJ. Coordinate regulation of estrogen-mediated fibronectin matrix assembly and epidermal growth factor receptor transactivation by the G protein-coupled receptor, GPR30. Mol Endocrinol. 2009. 23:1052–1064.

7. Lapensee EW, Tuttle TR, Fox SR, Ben-Jonathan N. Bisphenol A at low nanomolar doses confers chemoresistance in estrogen receptor-alpha-positive and -negative breast cancer cells. Environ Health Perspect. 2009. 117:175–180.

8. Smith HO, Arias-Pulido H, Kuo DY, Howard T, Qualls CR, Lee SJ, et al. GPR30 predicts poor survival for ovarian cancer. Gynecol Oncol. 2009. 114:465–471.

9. Smith HO, Leslie KK, Singh M, Qualls CR, Revankar CM, Joste NE, et al. GPR30: a novel indicator of poor survival for endometrial carcinoma. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2007. 196:386.e1–386.e9.

10. Filardo EJ, Graeber CT, Quinn JA, Resnick MB, Giri D, DeLellis RA, et al. Distribution of GPR30, a seven membrane-spanning estrogen receptor, in primary breast cancer and its association with clinicopathologic determinants of tumor progression. Clin Cancer Res. 2006. 12:6359–6366.

11. Leake R, Barnes D, Pinder S, Ellis I, Anderson L, Anderson T, et al. Immunohistochemical detection of steroid receptors in breast cancer: a working protocol. UK Receptor Group, UK NEQAS, The Scottish Breast Cancer Pathology Group, and The Receptor and Biomarker Study Group of the EORTC. J Clin Pathol. 2000. 53:634–635.

12. Revankar CM, Cimino DF, Sklar LA, Arterburn JB, Prossnitz ER. A transmembrane intracellular estrogen receptor mediates rapid cell signaling. Science. 2005. 307:1625–1630.

13. Kuo WH, Chang LY, Liu DL, Hwa HL, Lin JJ, Lee PH, et al. The interactions between GPR30 and the major biomarkers in infiltrating ductal carcinoma of the breast in an Asian population. Taiwan J Obstet Gynecol. 2007. 46:135–145.

14. Tu G, Hu D, Yang G, Yu T. The correlation between GPR30 and clinicopathologic variables in breast carcinomas. Technol Cancer Res Treat. 2009. 8:231–234.

15. Arias-Pulido H, Royce M, Gong Y, Joste N, Lomo L, Lee SJ, et al. GPR30 and estrogen receptor expression: new insights into hormone dependence of inflammatory breast cancer. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2010. 123:51–58.

16. Chen JQ, Russo J. ERalpha-negative and triple negative breast cancer: molecular features and potential therapeutic approaches. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2009. 1796:162–175.

17. Dennis MK, Burai R, Ramesh C, Petrie WK, Alcon SN, Nayak TK, et al. In vivo effects of a GPR30 antagonist. Nat Chem Biol. 2009. 5:421–427.

18. Levin ER. G protein-coupled receptor 30: estrogen receptor or collaborator? Endocrinology. 2009. 150:1563–1565.

PDF

PDF ePub

ePub Citation

Citation Print

Print

XML Download

XML Download