This article has been

cited by other articles in ScienceCentral.

Abstract

Severe fever with thrombocytopenia syndrome (SFTS) is an emerging febrile illness. While many kinds of severe complications including acute renal failure have been reported, rhabdomyolysis is rarely reported in association with SFTS. A 54-year-old female farmer was admitted with fever and diffuse myalgia. Laboratory finding showed thrombocytopenia, leukopenia, azotemia, extremely elevated muscle enzyme levels and myoglobinuria. We describe a fatal case of rhabdomyolysis with acute renal failure complicated by SFTS.

Keywords: Severe fever with thrombocytopenia syndrome, Rhabdomyolysis, Acute renal failure

Introduction

Rhabdomyolysis is a clinical and laboratory syndrome resulting from muscle injury and release of intracellular muscle constituents into the blood. The clinical symptoms vary from asymptomatic to life-threatening conditions such as acute renal failure, electrolyte imbalance and disseminated intravascular coagulation [

1]. Infections account for about 5% of rhabdomyolysis cases [

2]. Both viral and bacterial infections can be responsible, either by direct muscle invasion, release of myotoxic cytokines during infection, or autoimmune myositis [

34]. In addition, medical conditions such as dehydration, fever, and rigors accompanied by sepsis can lead to rhabdomyolysis [

5].

Severe fever with thrombocytopenia syndrome (SFTS) is a newly emerging febrile illness first reported in China in 2011. In the multi-organ failure phase, many kinds of severe complications including acute renal failure can occur but SFTS associated with rhabdomyolysis is rare [

6]. Here, we describe a case of rhabdomyolysis with acute renal failure complicated by SFTS.

Case Report

A 54-year-old female farmer with no significant past medical history was admitted to the local hospital on September 23, 2014, with a 7-day history of fever, myalgia, fatigue and poor oral intake. She lived in Jecheon-Si, Chungchung Province, South Korea and had climbed a mountain 2 weeks before admission. She was treated with antipyretics and fluid therapy but her symptoms were not relieved. On the fifth day after admission, she suddenly became somnolent and could not follow commands. Laboratory tests showed thrombocytopenia, leukopenia, elevated aspartate aminotransferase and alanine aminotransferase. On the same day, the patient was transferred to our hospital.

On examination, temperature was 37.2°C, blood pressure 125/81 mm/Hg, pulse 105 beats per minute, respiratory rate 22 breaths per minute, and oxygen saturation 92% in ambient air. She appeared acutely ill and was confused. Her Glasgow coma scale was 13. Pupil light reflex was normal and no meningeal irritation signs were observed. The conjunctivae were clear, and there were no palpable lymph nodes except for both inguinal areas. No insect bite site, eschar, skin rash, or ecchymosis was found.

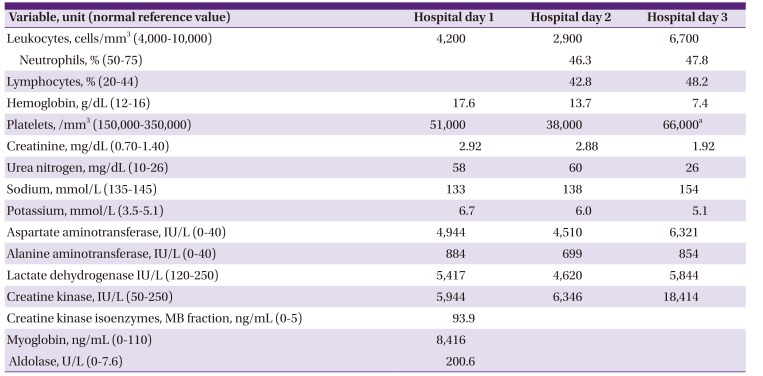

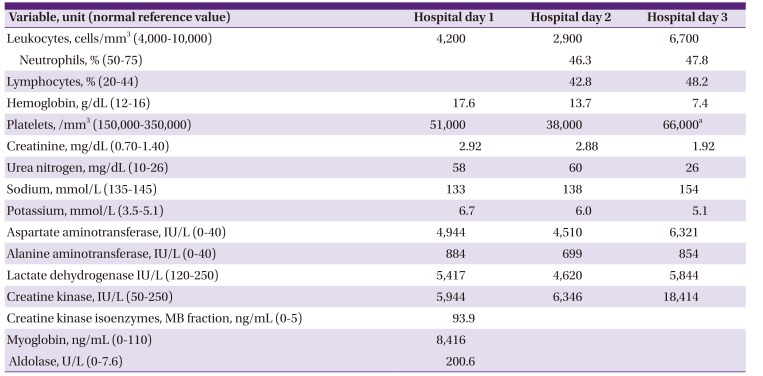

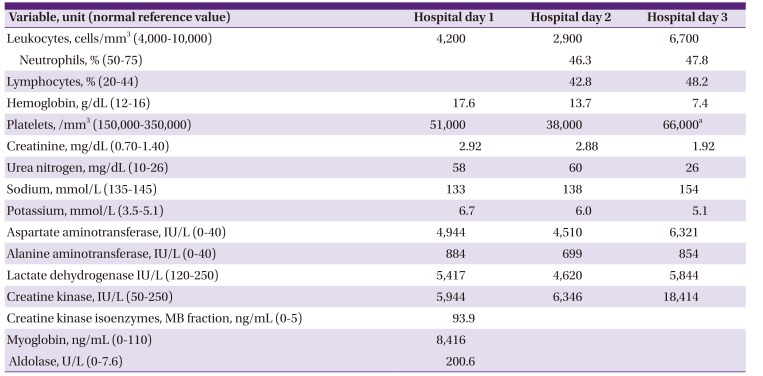

A complete blood cell count revealed mild leucopenia and thrombocytopenia, and blood chemistry and electrolyte tests showed azotemia, hyperkalmeia, elevated liver enzymes, substantially increased creatinie kinase, myoglobin and aldolase suggesting rhabdomyolysis (

Table 1). Blood cultures for bacteria were negative as were serum serology tests on the 14th day of illness for antibodies against Hantaan virus,

Leptospira interrogans,

Orientia tsutsugamushi, and Rickettsia typhi. A reverse transcriptase polymerase chain reaction assay for SFTS virus was performed but the result was not obtained at the time. A plain chest radiograph showed mild pulmonary congestion with bilateral pleural effusion. A computed tomography (CT) scan of the abdomino-pelvis revealed no evidence of structural lesions in the hepatobiliary system or kidney. Brain CT and magnetic resonance imaging provided no evidence of any acute intracranial process.

Table 1

Laboratory data

|

Variable, unit (normal reference value) |

Hospital day 1 |

Hospital day 2 |

Hospital day 3 |

|

Leukocytes, cells/mm3 (4,000-10,000) |

4,200 |

2,900 |

6,700 |

|

Neutrophils, % (50-75) |

|

46.3 |

47.8 |

|

Lymphocytes, % (20-44) |

|

42.8 |

48.2 |

|

Hemoglobin, g/dL (12-16) |

17.6 |

13.7 |

7.4 |

|

Platelets, /mm3 (150,000-350,000) |

51,000 |

38,000 |

66,000a

|

|

Creatinine, mg/dL (0.70-1.40) |

2.92 |

2.88 |

1.92 |

|

Urea nitrogen, mg/dL (10-26) |

58 |

60 |

26 |

|

Sodium, mmol/L (135-145) |

133 |

138 |

154 |

|

Potassium, mmol/L (3.5-5.1) |

6.7 |

6.0 |

5.1 |

|

Aspartate aminotransferase, IU/L (0-40) |

4,944 |

4,510 |

6,321 |

|

Alanine aminotransferase, IU/L (0-40) |

884 |

699 |

854 |

|

Lactate dehydrogenase IU/L (120-250) |

5,417 |

4,620 |

5,844 |

|

Creatine kinase, IU/L (50-250) |

5,944 |

6,346 |

18,414 |

|

Creatine kinase isoenzymes, MB fraction, ng/mL (0-5) |

93.9 |

|

|

|

Myoglobin, ng/mL (0-110) |

8,416 |

|

|

|

Aldolase, U/L (0-7.6) |

200.6 |

|

|

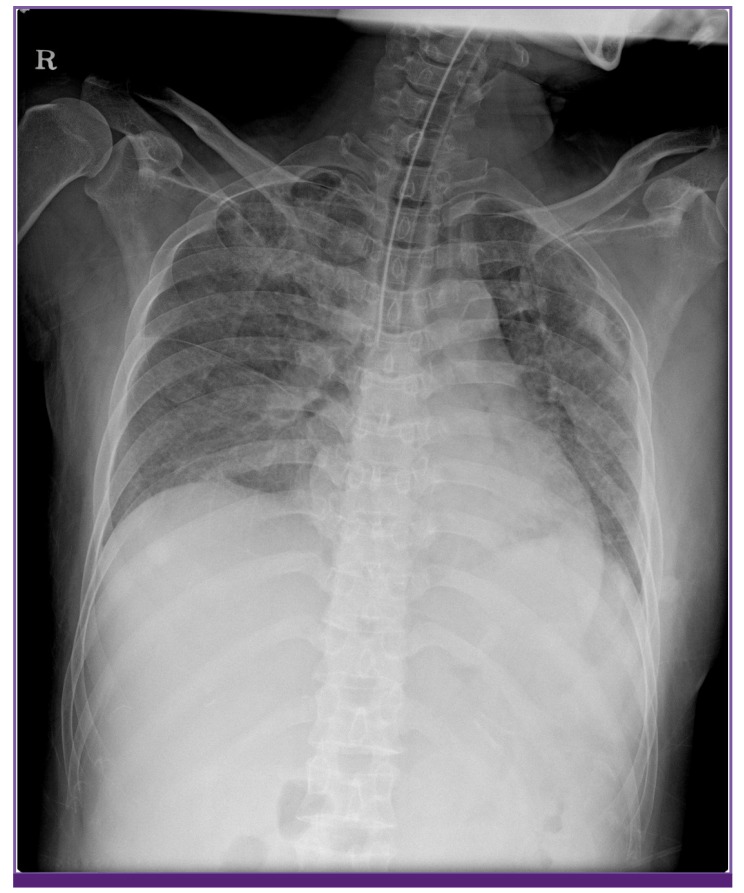

The patient was admitted to the medical intensive care unit from the emergency room. Intravenous piperacillin/tazobactam and levofloxacin were administered empirically. Emergent continuous renal replacement therapy was performed to correct the metabolic acidosis and hyperkalemia resulting from the rhabdomyolysis. However, on the third hospital day, the patient died due to rapidly progressive acute respiratory distress syndrome and multiple organ failure (

Fig. 1). After she died, SFTS virus was demonstrated by reverse transcriptase polymerase chain reaction at the Division of Arboviruses in the Korea Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

Figure 1

Chest X-ray on hospital day 3 shows increased bilateral diffuse opacities suggesting progressive acute respiratory distress syndrome.

Discussion

Since the first SFTS case was reported in Korea in May 2012 [

7], 35 cases have been reported to March, 2014. All the cases developed between May and November. Of the 35 patients, 19 (71%) were farmers or forest workers and 26 (74%) lived in rural areas [

8]. In our case, the patient was a farmer and lived in a rural area, and she presented with myalgia, fever, and thrombocytopenia in the month of August. Hence, this is a typical case of SFTS in South Korea. However, while in hospital, the patient suffered from fatal rhabdomyolysis probably complicated by the SFTS, and this combination has been rarely reported in the literature. In addition to SFTS, other acute febrile diseases such as leptospirosis [

9], human granulocytic anaplasmosis [

10], scrub typhus [

11], hemorrhagic fever renal syndrome [

12], that are known to be associated with rhabdomyolysis, were considered as differential diagnoses. Because we were unable to obtain paired sera due to the rapid fatal course, it is impossible to definitely rule out co-infection with some other agent of acute febrile disease. However, to our knowledge, no cases of co-infection with SFTS virus and a similar agent have been reported.

We should also consider other possible causes of the rhabdomyolysis including trauma or a non-traumatic origin such as drug, toxin, electrolyte disorder or seizure. That is, it is possible that the rhabdomyolysis had a non-traumatic exertional cause such as seizure because the patient was confused and showed intermittent limb tremor on presentation. The seizure could have been triggered by meningitis, encephalitis or spontaneous intracranial hemorrhage due to the thrombocytopenia. The patient underwent gadolinium-enhanced brain MRI but there was no evidence of encephalitis or hemorrhage. Further evaluation including lumbar puncture and electroencephalography was planned but could not be performed because the patient was in prone position due to rapidly progressive acute respiratory distress syndrome. Since seizure-like motion was not seen around the time of hospitalization, and muscle enzymes gradually increased after the use of a neuromuscular blocker, we assume that seizure was unlikely to be the main contributor to the rhabdomyolysis. Taken together, these considerations suggest that the rhabdomyolysis was complicated by SFTS rather than by some other medical condition.

A variety of acute viral infections including influenza, parainfluenza, coxsackievirus, enterovirus, adenovirus and herpes simplex virus have been associated with rhabdomyolysis [

2]. SFTS cases complicated mainly by rhabdomyolysis in initial presentation is rarely reported. To our knowledge, only one case has been reported [

13]. However, considering that myalgia was observed in 74% of patients with SFTS and elevated creatinine kinase was found in up to 79%, the actual incidence of rhabdomyolysis associated with SFTS may be higher [

614]. Thus, if the patients presented with fever, thrombocytopenia and rhabdomyolysis, clinician should consider SFTS as a differential diagnosis. The mechanism leading to the rhabdomyolysis remains unclear in viral infection. Potential hypotheses include direct muscular invasion by virus and immune mediated inflammatory process, however, histologic examination of involved muscle biopsies showed mainly tissue degeneration, necrosis, and regeneration, but few inflammatory cells in majority of patients [

15]. Other postulated hypothesis is muscular damage due to excessive cytokine production. In SFTS patients, overwhelming cytokine production is known to be associated with severe disease, which suggests that myotoxic cytokines play a key role in the rhabdomyolysis [

316]. Thus, although further studies are needed on this area, SFTS virus should be listed as a cause of rhabdomyolysis,

In conclusion, although rhabdomyolysis is a rarely reported complication in SFTS patients, it should be considered in patients who present with severe myalgia and markedly elevated creatine kinase levels.

Acknowledgement

This study was supported by a grant from the Korea Health Technology R&D Project through the Korea Health Industry Development Institute (KHIDI), funded by the Ministry of Health & Welfare, Republic of Korea (grant no. HI15C2774).

References

1. Huerta-Alardín AL, Varon J, Marik PE. Bench-to-bedside review: Rhabdomyolysis -- an overview for clinicians. Crit Care. 2005; 9:158–169. PMID:

15774072.

2. Singh U, Scheld WM. Infectious etiologies of rhabdomyolysis: three case reports and review. Clin Infect Dis. 1996; 22:642–649. PMID:

8729203.

3. Konrad RJ, Goodman DB, Davis WL. Tumor necrosis factor and coxsackie B4 rhabdomyolysis. Ann Intern Med. 1993; 119:861.

4. Naylor CD, Jevnikar AM, Witt NJ. Sporadic viral myositis in two adults. CMAJ. 1987; 137:819–821. PMID:

2832046.

5. Abe M, Higuchi T, Okada K, Kaizu K, Matsumoto K. Clinical study of influenza-associated rhabdomyolysis with acute renal failure. Clin Nephrol. 2006; 66:166–170. PMID:

16995338.

6. Deng B, Zhou B, Zhang S, Zhu Y, Han L, Geng Y, Jin Z, Liu H, Wang D, Zhao Y, Wen Y, Cui W, Zhou Y, Gu Q, Sun C, Lu X, Wang W, Wang Y, Li C, Wang Y, Yao W, Liu P. Clinical features and factors associated with severity and fatality among patients with severe fever with thrombocytopenia syndrome Bunyavirus infection in Northeast China. PLoS One. 2013; 8:e80802. PMID:

24236203.

7. Kim KH, Yi J, Kim G, Choi SJ, Jun KI, Kim NH, Choe PG, Kim NJ, Lee JK, Oh MD. Severe fever with thrombocytopenia syndrome, South Korea, 2012. Emerg Infect Dis. 2013; 19:1892–1894. PMID:

24206586.

9. Turhan V, Atasoyu EM, Kucukardali Y, Polat E, Cesur T, Cavuslu S. Leptospirosis presenting as severe rhabdomyolysis and pulmonary haemorrhage. J Infect. 2006; 52:e1–e2. PMID:

16051370.

10. Heller HM, Telford SR 3rd, Branda JA. Case records of the Massachusetts General Hospital. Case 10-2005. A 73-year-old man with weakness and pain in the legs. N Engl J Med. 2005; 352:1358–1364. PMID:

15800232.

11. Young PC, Hae CC, Lee KH, Hoon CJ. Tsutsugamushi infection-associated acute rhabdomyolysis and acute renal failure. Korean J Intern Med. 2003; 18:248–250. PMID:

14717236.

12. Chavanet P, Corgibet F, Courtois B, Monpoint S, Chalopin JM, Portier H. Hemorrhagic fever with renal syndrome. A case with diarrhea and rhabdomyolysis. Presse Med. 1985; 14:1290–1291.

13. Deng B, Cui W, Wen Y, Zhou Y, Wang W, Liu P. A case of a male presenting with fever, myalgia, leucopenia, thrombocytopenia and acute kidney injury. J Clin Virol. 2012; 55:285–288. PMID:

22819538.

14. Cui N, Liu R, Lu QB, Wang LY, Qin SL, Yang ZD, Zhuang L, Liu K, Li H, Zhang XA, Hu JG, Wang JY, Liu W, Cao WC. Severe fever with thrombocytopenia syndrome bunyavirus-related human encephalitis. J Infect. 2015; 70:52–59. PMID:

25135231.

15. Fadila MF, Wool KJ. Rhabdomyolysis secondary to influenza a infection: a case report and review of the literature. N Am J Med Sci. 2015; 7:122–124. PMID:

25839005.

16. Liu Q, He B, Huang SY, Wei F, Zhu XQ. Severe fever with thrombocytopenia syndrome, an emerging tick-borne zoonosis. Lancet Infect Dis. 2014; 14:763–772. PMID:

24837566.