INTRODUCTION

Alzheimer's disease (AD) is a progressive neurodegenerative disorder characterized by declining memory and cognitive function. In addition to these cognitive symptoms, most patients suffer from neuropsychiatric symptoms called 'behavioral and psychological symptoms of dementia (BPSD)'. Recently, BPSD have been increasingly recognized as an important part of the symptom of AD. They occur in 80-90% of patients with AD,

1,

2 affecting the quality of life of both patient and caregiver, resulting in change of patient's lifestyle and management.

3

AD patients with BPSD tend to lack of concentration while taking cognitive tests, and may show low performance on these tests. Furthermore, AD patients with BPSD frequently refuse to take these tests. Consequently, all or some part of neuropsychological tests may be left behind as missing values in specific neuropsychological tests. Due to these problems, it is difficult to complete all neuropsychological test battery in AD patients with BPSD.

Generally, if missing values occur in considerable portions of a study, increasing the sample population may be an appropriate statistical option. However, if increasing the sample population is difficult due to rare occurrence of such cases, missing values may reduce the precision of calculated statistics because there is less information than originally planned. Furthermore, if the missing mechanism is not at random, the result can be misleading. Another concern is that the assumptions behind many statistical procedures are based on complete cases, therefore missing values can complicate the theory required.

We studied herein the number of missing values of neuropsychological tests occurring in AD patients with BPSD, sub-domains of BPSD related with missing values and their influence on the profile of neuropsychological test results. Finally, after the imputation of these missing values, we compared observed and adjusted data for AD with BPSD and without BPSD.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Patients

An initial 1212 patients with dementia were screened from March 2003 to January 2012 at the Hyoja Geriatric Hospital. From this initial screening, 159 patients with probable AD (these patients were newly diagnosed and never medicated before visiting the hospital) were recruited to be the subjects of this study. Among them, 127 patients were suffering from BPSD and others had no BPSD. All patients included in this study met National Institute of Neurological and Communicative Disorders and Stroke-Alzheimer's Disease and Related Disorders Association criteria for probable AD.

4 The patients were drug-naïve, except for episodic hypnotics that were taken for sleep disturbances. Patients who were taking psychotropic drugs, including antipsychotics, antidepressants, anticonvulsants, benzodiazepines, and cholinesterase inhibitors, and not educated were excluded from this study.

The diagnostic evaluation included complete medical history, physical and neurological evaluation, comprehensive neuropsychological test, routine laboratory test, and brain magnetic resonance imaging or computed tomography scans. The age at the onset of dementia was defined as the time of onset of memory disturbances that exceeded episodic forgetfulness. After complete description of the study was given to subjects, and caregivers, written informed consent was obtained from the patients or caregivers. This study was approved by the Local Ethics Committee.

Neuropsychological examinations

All study subjects underwent the Seoul Neuropsychological Screening Battery,

5 a neuropsychological battery that includes standardized and validated tests of various cognitive domains. The test assesses attention, language, praxis, calculation, visuoconstructive function, verbal and visual memory, and frontal/executive functions and provides numeric scores in most test items. Among them, digit span (forward and backward), the Korean version of the Boston Naming Test, calculation, ideomotor praxis, the Rey-Osterrieth Complex Figure Test (RCFT) (copying, immediate and 20-min delayed recall and recognition), the Seoul Verbal Learning Test (SVLT) (three learning-immediate recall trials of a 12 item list, a 20-min delayed recall trial for the 12 items), contrasting program test/go-no-go test, a test of semantic fluency and letter-phonemic fluency (the Controlled Oral Word Association Test, or COWAT), Stroop test (Color Word Stroop Test or CWST; correct number of responses for word reading and naming the color of the font for 112 items during a two-min period) were adopted for this study. All participants underwent neuropsychological tests using the same protocol. When tests could not be completed for any reasons, we repeated the missed test in another day by the same examiner. Nevertheless, if we were confronted with missing values, then we distinguished between missing values due to behavioral disturbances and missing values due to other reasons (e.g. communication problem, medical illness etc.). Only missing values due to behavioral problems were the subjects of this study.

Behavioral rating scale

The Korean version of the NPI (K-NPI),

6 which is a retrospective informant-based rating scale for the behavioral and psychological symptoms in patients with dementia, was used for the evaluation of neuropsychiatric symptoms. This scale addresses 12 specific behavioral and psychological symptoms; delusions, hallucinations, agitation-aggression, depression, anxiety, euphoria, apathy, disinhibition, irritability, aberrant motor behavior, sleep disturbances, and eating abnormalities. The K-NPI gives a composite score for each domain that is the product of frequency by severity of subscores. The total K-NPI score was calculated by adding the 12 composite scores. The test-retest reliability and internal consistency of the K-NPI was assessed in a previous study.

6

In order to assess global dementia severity, the Korean version of the Mini-Mental State Examination (K-MMSE),

7 Clinical Dementia Rating Scale (CDR),

8 and the Clinical Dementia Rating Scale-Sum of Boxes (CDR-SB) were used. A Barthel index

9 for the activities of daily living evaluation, and a Geriatric Depression Scale (GDS)

10 for depression were also assessed.

Statistical analysis

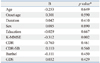

First, the baseline characteristics of the AD patients with and without BPSD were assessed by using Student's two-tailed t-tests and chi-square tests. Second, missing values in each neuropsychological test were assessed. Third, we computed Pearson's correlation coefficients between the K-NPI sub-domains and the number of missing values in individual neuropsychological tests for significance using the two tailed tests.

For all test scores, means were calculated. Next, while we replaced each missing value in AD without BPSD by series mean, in AD with BPSD, we replaced each missing value by the worst score found on that particular test. After this adjustment, we calculated means of the adjusted scores.

A significance level of 0.05 (two-tailed) was set for all analyses, which were performed by using the SPSS version 18.0 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA) for Windows.

DISCUSSION

This study aimed to assess the prevalence of missing values, relation between BPSD and missing values of the neuropsychological test, and value of missing values analysis in AD patients with BPSD.

Most neuropsychological tests assessing various cognitive domains require some degree of attention and cooperation of patients. If examinees have behavior problems or have severe specific cognitive impairment, there is a high probability of specific neuropsychological tests being left unfinished. For example, agitation, inability to correct, loss of insight into performance, perseverative behavior, stereotypy behavior, and stimulus boundedness were strongly related with missing data analysis in patients with frontotemporal dementia.

11

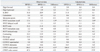

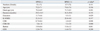

In contrast to this frontotemporal dementia study, our study showed that delusions, depression, apathy, and aberrant motor behaviors were closely related with missing values of test. Among them, delusions and aberrant motor behaviors were more significantly correlated with missing values than other K-NPI sub-domains (

Table 4). The reason for the close relationship between delusions with missing data is not clear. One possible explanation is that delusion is closely related with agitation and aberrant motor behavior,

12,

13 and these physical symptoms apparently lead to problems in assessing these time-consuming tests. Moreover, patients with delusions frequently have persecutory delusion,

14,

15 and as a results some patients with this delusion may resist diagnostic evaluations.

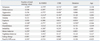

The BPSD showed the largest effect on tests measuring the frontal functions (contrasting programs, CWST word, CWST color and COWAT phonemic). Missing values in these tests (sensitive markers for impairment of frontal function) may blur the differences of cognitive sub-domain functions in AD with BPSD. In contrast, however, tests such as the SVLT immediate and delay recall (sensitive markers for temporal function) showed nearly no differences in missing values between AD with BPSD and without BPSD.

The missing values were differently replaced in each group. According to missing value analysis, missing values in AD without BPSD were replaced by the mean scores. However, because the missing values of AD with BPSD were correlated with K-NPI scores, these were replaced by the lowest observed values in AD with BPSD. The effect of the data imputation was largest for tests measuring frontal function. As a consequence, the difference between test results of frontal function becomes clear, and more differentiated pattern of cognitive deficits is found in AD with BPSD.

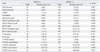

In our study, the total missing data number was significantly related with K-MMSE scores, while global cognitive scale (CDR) was not (

Table 2). These discrepancies may result from study population characteristics. Most of our study subjects were in the mild stage dementia. Therefore, CDR staging, which is only five grade scale, may not reflect the differences.

The relationship of neurocognitive functions in AD patients with BPSD versus those without BPSD has been the subject of considerable debate. While some studies have noted difficulties in differentiating AD with and without BPSD on neuropsychological variables and have questioned the specificity of deficient sub-cognitive domains in AD patients with BPSD compared with AD patients without BPSD,

16 other studies have shown a relationship with more cognitive impairment and frontal lobe dysfunctions.

17,

18

Considering the fact that considerable portion of certain neuropsychological tests were left unfinished in our study, there is a possibility that missing values may have influenced our overall results, even though our study subjects were mainly mildly demented patients. Perhaps, the missing values analysis might provide a clue for this finding. In this study, most patients without BPSD showed no difficulties in completing the neuropsychological test, therefore most neuropsychological tests were assessable, thus providing the investigator with more complete data set.

In a previous study,

19 the missing values (or non-response) on the mini mental state examination were explored. This study concluded that non-response did not occur randomly, and scoring non-response as error was more likely to reflect the severity of dementia. In randomized controlled clinical trial study, they showed that drop out (i.e. missing values) does not occur randomly, therefore the data can influence the overall results.

20 Due to these missing values, the neuropsychological tests are biased toward the null effect. This might have obscured the characteristic cognitive deficit of the AD patients with BPSD.

Nevertheless, replacing all missing values irrespective of its cause is not valid and feasible for all patient groups and has to be done with caution. Missing values may be caused by other reasons, such as sensory impairments, aphasia, or external factors caused by the examiner. In these cases, the failure to complete a specific neuropsychological test does not necessarily indicate a specific cognitive deficit, but is more likely to reflect other non-cognitive factors.

In the present study, BPSD was found to be significantly correlated with missing values, therefore, we replaced only the missing values in AD patients with BPSD by the lowest observed scores. Missing values due to other reasons were excluded from this study. In our present study, therefore, replacing missing values due to BPSD by the lowest scores is justified.

However, this study had several limitations. First, sample size was relatively small compared to the number of factors. Second, this study included mostly milder dementia patients. Since the BPSD was more prevalent in moderate to severe stage of dementia than mild stage of dementia,

21 these methods were expected to be more applicable to moderate to severe stage of dementia groups. Third, even though we excluded the missing values due to other problems caused by examiner and other researcher, the possibility of false positive and negative cases could not completely be ruled out. Fourth, though K-MMSE score, which is only statistically influencing factor for the total missing data number, was not different between AD patients with and without BPSD, the patients with BPSD showed more significant global cognitive dysfunctions. Therefore, there was possibility that these between-group differences might have originated from these severity differences. Finally, our study was a hospital-based study, therefore it may not represent a real community.

In conclusion, our results showed that missing values in the context of BPSD did not occur at random and provided useful information. Using data imputation, a more differentiated picture of cognitive deficits in AD with BPSD is suggested without the need to exclude those patients who displayed behavioral disturbances. Consequently, more realistic and reliable statistical analysis should be carried out and further research on the clinical picture of AD with BPSD and its relation to other BPSD would provide the answer.

PDF

PDF ePub

ePub Citation

Citation Print

Print

XML Download

XML Download