This article has been corrected. See "Erratum to "The First Case of Familial Mediterranean Fever Associated with Renal Amyloidosis in Korea" by Koo KY, et al. (Yonsei Med J 2012;53:454-8.)" in Volume 53 on page 670.

This article has been corrected. See "Erratum to "The First Case of Familial Mediterranean Fever Associated with Renal Amyloidosis in Korea" by Koo KY, et al. (Yonsei Med J 2012;53:454-8.)" in Volume 53 on page 873.

Abstract

Familial Mediterranean fever (FMF) is an auto-inflammatory disease characterized by periodic episodes of fever and recurrent polyserositis. It is caused by a dysfunction of pyrin (or marenostrin) as a result of a mutation within the MEFV gene. It occurs mostly in individuals of Mediterranean origin; however, it has also been reported in non-Mediterranean populations. In this report, we describe the first case of FMF in a Korean child. As eight-year-old boy presented recurrent febrile attacks from an unknown cause, an acute scrotum and renal amyloidosis. He also showed splenomegaly, lymphadenopathy, pleural effusion, ascites and elevated acute phase reactants. After MEFV gene analysis, he was diagnosed as FMF combined with amyloidosis.

Familial Mediterranean fever (FMF) is a hereditary auto-inflammatory disease, caused by mutation(s) in the MEFV gene.1-4 It manifests as repetitive fever episodes combined with one or more symptoms of sterile arthritis or serositis.1-4 FMF is endemic to those of Mediterranean descent; however, sporadic cases have been reported in non-Mediterranean persons beyond this region.4-6 Especially, reports of FMF are uncommon in the Far East although few reports and mutation studies have been conducted in Japanese patients.6 Accordingly, FMF is not familiar to clinicians in this area and might be misdiagnosed as other auto-inflammatory diseases. The Tel-Hashomer criteria can help with clinically diagnosing the disease; however, the same criteria are also indicative of inflammatory diseases. The MEFV gene for FMF has been cloned and DNA analysis can be useful in diagnosing FMF when patient(s) do not wholly fulfill the diagnostic criteria. Herein, we describe the first case of FMF confirmed by molecular analysis of the MEFV gene in a Korean patient who showed recurrent clinical symptoms.

An eight-year-old boy was referred to our hospital due to generalized edema for two weeks and sudden onset of scrotal swelling that occurred two days prior to admission. Since one year before the admission, he had repetitive, acute, self-limited episodes of fever at varying intervals with an elevated level of acute phase reactants. Despite thorough evaluation, the reason for the fever was unable to be determined. After an initial examination, he had been followed up under the impression of juvenile rheumatoid arthritis even though he did not demonstrate joint symptoms. Family history revealed that his father died due to myocardial infarction at the age of 40 and there was no history of renal disease, periodic fever or auto-inflammatory disease.

Upon physical examination, his fever was 38.4℃, blood pressure was 108/75 mm Hg, and body weight increased from 23 kg to 26 kg in last two weeks prior to admission. Pretibial pitting edema and swollen abdomen were also observed without rash. Laboratory findings on admission showed inflammatory conditions of very high C-reactive protein (140 mg/L) and high erythrocyte sedimentation rate (120 mm/hr). Anemia (8.4 g/dL), hypoalbuminemia (1.0 g/dL), and markedly elevated fibrinogen (1029 mg/dL) were observed as well. Massive nephrotic-range proteinuria (urine protein/creatinine ratio was 14.49, total microprotein 12297 mg/day, microalbumin 10249 mg/day) was observed with 24-hour collected urine. Different markers for autoimmune diseases such as anti-nuclear antibody, and anti-cardiolipin antibody were negative and complement levels as well as immunoglobulin concentrations were all within normal range.

After admission, he complained of abdominal pain and abdominal ultrasonography revealed slightly increased renal parenchymal echogenicity with splenomegaly (11 cm) and no hydrocele in both scrotal sacs. Abdominal computed tomography showed enlargement of bilateral kidneys; a well-enhancing mass lesion in the right common iliac chain; small bowel mesentery, suspected as lymphadenopathy; a small amount of ascites; and pleural effusion. Echocardiography showed minimal pericardial effusion with decreased deceleration time of the mitral valve (80-100 ms), which suggested a poor prognosis.

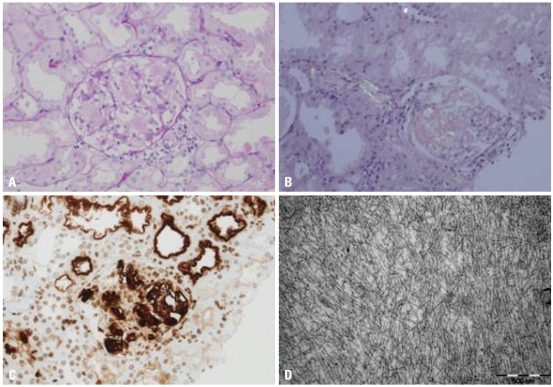

Renal biopsy was performed for evaluation of the massive proteinuria, and the pathologic diagnosis was confirmed as amyloidosis type AA (Fig. 1). Tests for monoclonal gammopathy to rule out AL amyloidosis, including serum/urine protein electrophoresis, immunofixation electrophoresis, and serum κ-, λ-free light chain assays, were all negative. Cochicine therapy was started with a dose of 0.025 mg/kg/day under the impression of FMF and his clinical symptoms gradually improved.

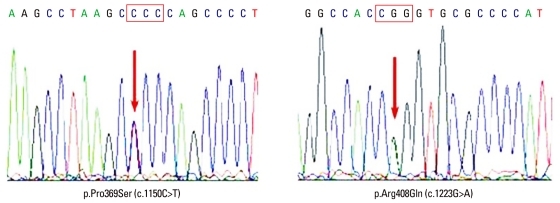

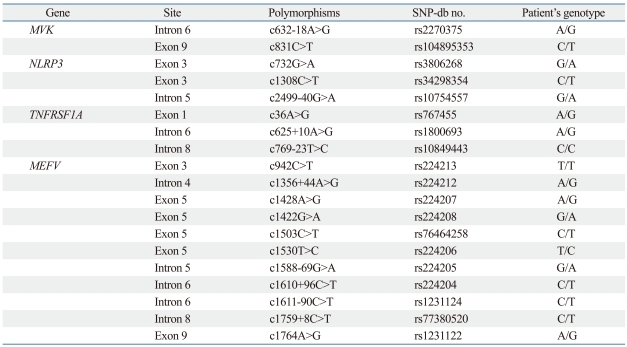

In order to make the clinical diagnosis, the clinical entities of periodic fever and systemic inflammatory reactions combined with amyloidosis were considered, which were indicative of FMF (OMIM no. 249100), familial periodic fever (FPF, TRAPS; OMIM no. 142680), hyperimmunoglobulinemia D with periodic fever syndrome (HIDS; OMIM no. 260920), and Muckle-Wells syndrome (MWS; OMIM no. 191900). The patient was able to be diagnosed as FMF since he showed typical attacks fulfilling three major criteria (pleuritis, fever and incomplete abdominal attack) of the Tel-Hashomer criteria. To verify the underlying cause of AA amyloidosis, DNA analysis of the MEFV gene was initially performed and two point mutations (p.Pro369Ser, p.Arg408Gln) were identified (Fig. 2). For differential diagnosis, other genes, including MVK for HIDS, NLRP3 for MWS and TNFRSF1A for FPF, that cause similar phenotypes were also analysed. Only several SNPs were identified in the analysis of MVK, NLRP3 and TNFRSF1A genes (Table 1).

FMF is a hereditary auto-inflammatory disease characterized by periodic episodes of fever and polyserositis at irregular intervals.1-4 In 1960, Fox and Morrelli described the first case of FMF in a patient of non-Mediterranean ethnic origin.7 Thereafter, sporadic cases among Ashkenazi Jews, Germans and Anglo-Saxons have been continuously reported including Asians. Reasons for the differences in the prevalence of the disease in different ethnic groups are still unknown.1,4-7 The influence of environmental factors or a selective advantage of the heterozygote has been suggested in those from the Mediterranean area.8

In this report, the first case of familial Mediterranean fever in a Korean patient was described. The patient showed symptoms of renal amyloidosis, which leads to renal failure and increased mortality. Because of the rarity of the disease in Korea, FMF was not considered until he was diagnosed as having AA amyloidosis. The diagnosis of FMF is still based on clinical manifestations listed in the Tei-Hashomer criteria.2 Since colchicine therapy is essential for prevention and recovery from amyloidosis and other complications of FMF, early diagnosis is important.1-4 For this reason, the clinical symptoms of abdominal pain (90%), arthritis or arthralgia (85%), and chest pain (20%) need to be carefully evaluated when these symptoms are combined with periodic fever. In addition, serositis, such as pericarditis, as well as ascites and an acute scrotum are rarely afflicted. Recurrent attacks of triad symptoms, such as fever, arthritis and serositis as well as abnormal acute phase reactants in conjunction with an excellent response to colchicine were also suggestive of FMF.

The gene responsible for FMF, called MEFV, is mapped to chromosome 16p13.3, which encodes a 781 amino acid protein named pyrin (or marenostrin), and transmitted in an autosomal recessive or dominant pattern. Pyrin is expressed in the cytoplasm of mature neutrophils and monocytes and is thought to trigger the biosynthesis of neutrophil-specific transcription factors.1,2 More than 50 mutations have been described and five mutations (M694V, V726A, M694I, M680I, E148Q) are the most common mutations observed.1,3,4,11 Even though molecular DNA analysis is a powerful technique for the diagnosis of the disease, it should be noted that only 60% of patients showed pathologic mutations within the MEFV gene.1,2 Two point mutations (P369S, R408Q) that were observed in our patient, were not frequently detected in Western populations, including the Middle East.8 However, these mutations were reported in Japanese patients with the same genotype as our patient, carrying two mutations in cis-; however their phenotypic effects remain controversial.12 Ryan, et al.13 studied the functional significance of P369S/R408Q mutations and concluded that these mutations are related with variable phenotypes and do not significantly affect interaction between pyrin and PSTPIP1. However, 5 of 22 patients carrying these mutations fulfilled Tel-Hashomer criteria for clinical diagnosis of FMF. Therefore, other genes causing periodic fever syndrome were analysed with negative results.

In addition to pathologic mutations in MEFV gene, environmental factors and interactions of other genes are emphasized in the expression of the clinical phenotype.13 It may be important factors in FMF patients with autosomal dominant inheritance carrying heterozygote mutation in MEFV gene. The case in this report fulfilled the Tel-Hashomer criteria for clinical diagnosis of FMF and carried two mutations in the MEFV gene without any pathologic mutations in the MVK, NLRP3 and TNFRSF1A genes. Even though the functional significance of P369S/R408Q has not been clearly elucidated, we assume that interactions with other genes may play some role in the phenotypic expression of these mutations. In a study on Turkish patients, the frequency of P369S was 7.6% and the genotype of P369S/E148Q was present in 15%.14

Clinical diagnosis of FMF is not easy, especially, in patients of non-Mediterranean ethnic origin. Our case showed severe symptoms including renal amyloidosis at an early age. The most common reason for renal amyloidosis in children in the Mediterranean area15 is FMF. There is also a possibility of another gene(s) responsible for the disease. About 40% of the patients with clinical symptoms of FMF show negative results upon DNA analysis. More data on the mutation spectrum of the MEFV gene and phenotypic characteristics will increase the further understanding of the function of the gene and the molecular pathogenesis of the disease.

References

1. Gedalia A. Kliegman RM, Behrman RE, Jenson HB, Stanton BF, editors. Hereditary periodic fever syndromes. Nelson textbook of Pediatrics. 2007. 18th ed. Philadelphia: W.B. Saunders Company;p. 1029–1031.

2. Katsenos S, Mermigkis C, Psathakis K, Tsintiris K, Polychronopoulos V, Panagou P, et al. Unilateral lymphocytic pleuritis as a manifestation of familial Mediterranean fever. Chest. 2008; 133:999–1001. PMID: 18398120.

3. Cekin AH, Dalbudak N, Künefeci G, Gür G, Boyacioğlu S. Familial Mediterranean fever with massive recurrent ascites: a case report. Turk J Gastroenterol. 2003; 14:276–279. PMID: 15048606.

5. Konstantopoulos K, Kanta A, Tzoulianos M, Dimou S, Sotsiou F, Politou M, et al. Familial Mediterranean fever phenotype II in Greece. Isr Med Assoc J. 2001; 3:862–863. PMID: 11729588.

6. Araki H, Onogi F, Ibuka T, Moriwaki H. [A Japanese family with adult-onset familial Mediterranean fever and periodic episodes of high fever and abdominal pain]. Nihon Shokakibyo Gakkai Zasshi. 2010; 107:427–431. PMID: 20203446.

7. Dormer AE, Hale JF. Familial Mediterranean fever: a cause of periodic fever. Br Med J. 1962; 1:87–89. PMID: 13887384.

8. Yepiskoposyan L, Harutyunyan A. Population genetics of familial Mediterranean fever: a review. Eur J Hum Genet. 2007; 15:911–916. PMID: 17568393.

9. Baş F, Kabataş-Eryilmaz S, Günöz H, Darendeliler F, Küçükemre B, Bundak R, et al. Type 1 diabetes mellitus associated with autoimmune thyroid disease, celiac disease and familial Mediterranean fever: case report. Turk J Pediatr. 2009; 51:183–186. PMID: 19480334.

10. Matos TC, Terreri MT, Petry DG, Barbosa CM, Len CA, Hilário MO. Autoinflammatory syndromes: report on three cases. Sao Paulo Med J. 2009; 127:314–316. PMID: 20169282.

11. Keskin G, Inal A, Sengül A, Cindoruk M, Haznedaroğlu S, Duranay M, et al. Phagocytic activity in familial Mediterranean fever. Yonsei Med J. 2000; 41:441–444. PMID: 10992804.

12. Sugiura T, Kawaguchi Y, Fujikawa S, Hirano Y, Igarashi T, Kawamoto M, et al. Familial Mediterranean fever in three Japanese patients, and a comparison of the frequency of MEFV gene mutations in Japanese and Mediterranean populations. Mod Rheumatol. 2008; 18:57–59. PMID: 18097735.

13. Ryan JG, Masters SL, Booty MG, Habal N, Alexander JD, Barham BK, et al. Clinical features and functional significance of the P369S/R408Q variant in pyrin, the familial Mediterranean fever protein. Ann Rheum Dis. 2010; 69:1383–1388. PMID: 19934105.

14. Caglayan AO, Demiryilmaz F, Ozyazgan I, Gumus H. MEFV gene compound heterozygous mutations in familial Mediterranean fever phenotype: a retrospective clinical and molecular study. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2010; 25:2520–2523. PMID: 19934083.

15. Bilginer Y, Akpolat T, Ozen S. Renal amyloidosis in children. Pediatr Nephrol. 2011; 26:1215–1227. PMID: 21360109.

Fig. 1

The mesangium is expanded by pinkish amorphous material (PAS, ×400) (A). This material shows apple green birefringence under the polarized microscopy after Congo red staining (×200) (B) and immunoreactivity to the amyloid A antibody (×200) (C). An electron microscopy reveals haphazardly arranged non-branching fibrils measuring 8-10 nm in diameter. (×50000) (D).

PDF

PDF ePub

ePub Citation

Citation Print

Print

XML Download

XML Download