INTRODUCTION

With changes in medical environments that affect doctors' humanism education, such as the development of medical technology, as well as shifts in demographics and the structure of diseases, medical schools in many countries are striving to improve their curricula (

1). The range of qualifications that society demands for "good doctors" has expanded, in the sense that professional doctors (who have medical knowledge and are aware of various techniques) are no longer sufficient. Now, doctors should also be moral and socially accountable. Since the 2000s, there has been an increase in public awareness, with a general consensus that humanism education should be reinforced in curricula throughout the years of medical school in Korea (

2).

Nowadays, humanism is considered an essential core quality, part of a doctor's professionalism when treating patients (

3). What are the important humanistic competencies that medical schools should teach? According to a study on doctors' core attributes, which surveyed students and professors in medical schools, hospital patients, and staff at individual clinics, the top traits of good doctors include (

4): accurate treatment and clinical expertise, followed by empathic ability with pain from the patient's perspective, personal development, moral judgment and actions, a kind attitude, a trusting relationship with patients and their family members, and providing service to the local community.

Presently, most of Korea's 41 medical colleges and schools advocate for the following criteria (ranked in importance from highest to lowest): medical expertise, professionalism (ethics, morality, social accountability, and attitude), social contributions (to local society and community), personal management and development (exploring diverse fields, self-reflection), and cooperation (a respect for diversity, trust, communication, patient-centered treatment) (

5).

Due to the changes in the model doctors wanted by the society, the scope of fundamental medical education is now expanding in order to cover more inclusive humanistic competency. The increasing number of courses in the medical humanities reflects such changes (

2). Values such as understanding of the self and others, professional and social accountability, and the patient-doctor relationship can be reinforced by fostering knowledge in the humanities; this can systematically lead to training doctors with the desired qualities, within the larger paradigm of doctor training after graduating from medical school.

As Korea is the country with the highest private medical school ratio in the world (31 of 41, or approximately 75%, of medical schools are private), the privatization of medical education occurred before the systematic identification of the public attributes of said education. Thus, the education of doctors was focused on cultivating professionals with a high degree of medical knowledge, resulting in a comparatively weak education in the philosophy or values that form the basis of medical technology (

6). Although there has been an increased interest in doctors' ethics and humanism since 2000, medical schools are limited in their systematic implementation of humanistic education due to the lack of specific regulations for education manuals for medical school students and medical residents (

2). Ever since the World Federation for Medical Education called for all countries to identify specific traits (suitable for each nation) by focusing on values in non-clinical and clinical areas (

7), the Korean government has worked to describe such traits and announced the "The global role of Korean doctor" in 2014 (

8). Based on the top five core humanistic attributes, doctors should 1) Prioritize the patient's health and safety; 2) Communicate and cooperate with patients, guardians, medical staff, and society; 3) Strive for a peaceful society and international cooperation; 4) Observe their professional duties; and 5) Continue to self-educate and conduct research.

Thus, there is a relatively clear consensus in society on the value and necessity of comprehensive humanism education in medical school curricula. However, the range of individual courses and topics in each medical school remains narrow, limited to medical ethics and accountability. These courses often appear to fail at comprehensively teaching general communication with society, subjective satisfaction and happiness of the doctors'. Moreover, because there are not enough teaching methods or programs that support corresponding curricula, many medical schools are adopting a one-directional lecture style for humanism education (

9). Thus, more realistic, specific strategies for the goals and teaching methods of humanism education need to be established in medical schools.

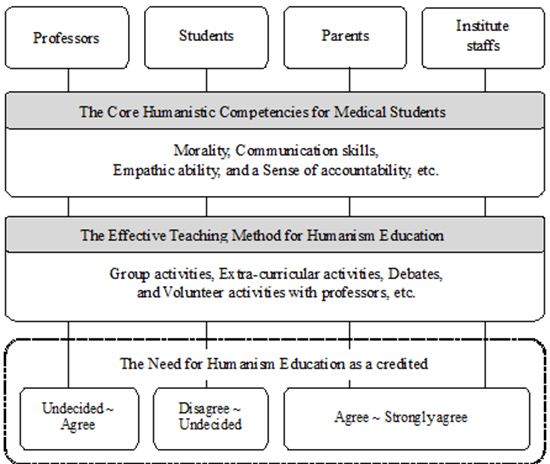

The authors conducted a survey in a medical school and interviewed students, professors, parents, and others associated medicine. The authors asked: 1) What essential humanistic competency should medical students have? 2) What is an effective way to teach humanistic competency? 3) Why is humanism education necessary, and what are its effects? Based on the results, the authors made several suggestions regarding the direction of future humanism education.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Participants

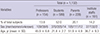

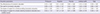

The participants were either involved in teaching medical students at Seoul National University College of Medicine in Korea, or believed they were able to judge students' values and attitudes. They consisted of 154 medical school professors (including clinicians who are also adjunct professors), 589 medical students (including pre-medical students), 228 parents, and 161 college and hospital staffs (such as nurses and laboratory technicians). A total of 1,132 people participated (

Table 1).

Table 1

Characteristics of the participants

|

Variables |

Total (n = 1,132) |

Professors

(n = 154) |

Students

(n = 589) |

Parents

(n = 228) |

Institute staffs

(n = 161) |

|

% of total subjects |

13.6 |

52 |

20.1 |

14.2 |

|

Sex (men/women/unknown) |

109/39/6 |

370/205/14 |

105/111/12 |

27/132/2 |

|

Age, yr (mean ± SD) |

45.9 ± 6.8 |

21.8 ± 2.7 |

51.9 ± 4.9 |

36.7 ± 9.3 |

Response variables (survey structure)

All participants answered nine questions that the researchers created. Question 1 asked, "In order of importance, select five humanistic competencies that medical students should have (among the twelve suggested below)." Question 2 asked, "To what degree do you think medical students in this school possess each humanistic competency? (Score each of the twelve qualities on a scale of 0 to 6: 0 = ‘not very much,' 6 = ‘very well.'"

The authors selected the items in the multiple choice questions after reviewing general virtues (known as humanistic competency) and qualities: morality and a sense of ethics (i.e., honesty), communication skills, empathic ability (seeing another's perspective, compassion for the pain of others), a sense of accountability, consideration for others, a wide perspective and respect for diversity, a sense of community and cooperativeness, altruism and service, critical thinking and problem-solving skills (conflict resolution), the ability to control one's behavior and emotions, handle stress, and manners.

Question 3 was a multiple-choice question that asked, "Select at least three effective methods for teaching humanistic competencies." The following examples were given: lectures, seminars and debates, regular one-on-one meetings and counseling with faculty, group activities, extra-curricular activities (sports, choir, music appreciation, art and other creative activities), humanities classes and debates, camping excursions and short trips, regular volunteer activities with professors, and education for parents.

Questions 4, 5, 6, and 7 were multiple-choice questions on a scale from 0 to 4 (0 = strongly disagree, 4 = strongly agree) regarding the effectiveness of humanism education, the need for it, the degree of support for schools providing it, and selecting it as a credited course. Questions 8 and 9 were short-answer questions. Number 8 related to assessment methods ("What method do you think is appropriate for evaluating a student's performance in the course as an official subject?") and number 9 covered other opinions on humanism education.

Data collection

Data were collected from March to May 2015 via printed, mailed, or e-mailed questionnaires. The printed questionnaires were a main source of data collection. The survey's purpose and content were presented on the first page, and all participants were requested to become fully familiar with it, and voluntarily decide to participate before answering. School faculty and some institute staff took part in the survey via email, but all the students submitted printed questionnaires. The parents, who had difficulty submitting the survey in person, mailed the questionnaire back to the authors with a stamped, addressed envelope. All the participants remained anonymous; only information on their age and gender were collected.

Statistical analysis

In the first question, which asked participants to select the top five humanistic competencies (out of twelve choices) based on order of importance, the trait chosen as most important was given 5 points. The fifth choice was given 1 point to calculate the mean score. In the third question, which asked participants to select at least three methods they think are effective for teaching humanism education, each choice was given 1 point, and the average frequency of selecting that choice was calculated. Excluding the two aforementioned questions, the answers to the rest of the questions were calculated based on Likert scale points, and the mean score was used for analysis. All data were analyzed with the software SPSS Statistics 19.0 (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, USA). The descriptive statistics, such as each sub-group's mean score, standard deviation, and frequency, were calculated for each question. Analysis of variance (ANOVA) and post-hoc testing were performed to compare the estimations between the groups.

Ethics statement

This study was approved by the institutional review board of Seoul National University Hospital (IRB No. E-1507-012-684). Since this was a minimal-risk study, the written consent of the individual subjects was waived by the board.

RESULTS

The core values of humanism in medical education

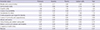

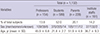

In all sub-groups, "morality and a sense of ethics" was chosen as the most important value. The second was a "sense of accountability," followed by "communication skills," "empathic ability," "mindfulness and tolerance," and a "wide perspective and respect for diversity."

Regarding the top three values that each sub-group selected, the professors chose "morality and a sense of ethics," a "sense of accountability," and "empathic ability." The students selected "morality and a sense of ethics," a "sense of accountability," and "communication skills." The parents opted for "morality and a sense of ethics," a "sense of accountability," and "communication skills." The employees chose "morality and a sense of ethics," "communication skills," and a "sense of accountability" (

Table 2).

Table 2

Mean of the importance scores on each humanistic value that medical students must have

|

Humanistic values |

Professors |

Students |

Parents |

Institute staffs |

Total |

|

Morality and a sense of ethics |

3.80 |

3.17 |

3.94 |

3.38 |

3.57 |

|

Communication skills |

1.75 |

2.05 |

1.64 |

2.16 |

1.90 |

|

Empathic ability |

1.96 |

1.70 |

1.55 |

1.33 |

1.63 |

|

A sense of accountability |

2.55 |

2.32 |

2.46 |

2.15 |

2.37 |

|

Consideration for others |

0.97 |

1.21 |

1.33 |

1.08 |

1.15 |

|

A wide perspective and respect for diversity |

0.91 |

0.84 |

0.87 |

0.93 |

0.88 |

|

A sense of community and cooperativeness |

0.65 |

0.92 |

0.84 |

1.19 |

0.90 |

|

Altruism and service |

0.39 |

0.42 |

0.54 |

0.29 |

0.41 |

|

Critical thinking and problem-solving skills |

0.87 |

0.81 |

0.52 |

0.60 |

0.70 |

|

Ability to control one's behavior and emotions |

0.58 |

0.59 |

0.68 |

0.83 |

0.67 |

|

A capacity to handle stress |

0.31 |

0.45 |

0.37 |

0.41 |

0.39 |

|

Manners |

0.24 |

0.49 |

0.47 |

0.67 |

0.47 |

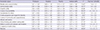

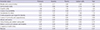

The results of assessing to what extent the medical students possessed each humanistic competency showed that most participants had nearly identical answers (as to whether students possessed the qualities to a high or low degree). Participants thought that students had a high "sense of accountability" and "morality and a sense of ethics (i.e., honesty)." Participants thought that students had a low degree of "empathic ability," "mindfulness and tolerance," "communication skills," "altruism and service," and a "sense of community and cooperation" (

Table 3). There was a small disparity in the distribution of the mean score in each sub-group; the parents and students evaluated the degree of each humanistic competency in students more highly than professors and institute staff.

Table 3

The scores on each humanistic value that medical students currently carrying out (mean ± SD)

|

Humanistic values |

Professors |

Students |

Parents |

Institute staffs |

F

|

Post-hoc*

(Scheffe)

|

|

Morality and a sense of ethics |

3.51 ± 1.04 |

3.69 ± 1.16 |

4.14 ± 1.21 |

3.44 ± 1.00 |

15.87†

|

1,4,2 < 3 |

|

Communication skills |

2.91 ± 1.09 |

3.38 ± 1.16 |

3.67 ± 1.21 |

2.94 ± 1.06 |

18.77†

|

1,4 < 2,3 |

|

Empathic ability |

2.63 ± 0.90 |

3.34 ± 1.13 |

3.42 ± 1.26 |

2.76 ± 1.16 |

26.88†

|

1,4 < 2,3 |

|

A sense of accountability |

3.79 ± 1.15 |

3.92 ± 1.22 |

4.52 ± 1.18 |

3.41 ± 1.04 |

28.23†

|

4 < 1,2 < 3 |

|

Consideration for others |

2.67 ± 0.92 |

3.49 ± 1.21 |

3.60 ± 1.30 |

2.73 ± 1.04 |

40.44†

|

1,4 < 2,3 |

|

A wide perspective and respect for diversity |

2.78 ± 1.05 |

3.54 ± 2.92 |

3.90 ± 1.25 |

3.09 ± 1.08 |

8.67†

|

1,4 < 2,3 |

|

A sense of community and cooperativeness |

2.68 ± 1.02 |

3.43 ± 1.16 |

3.69 ± 1.27 |

2.92 ± 1.15 |

29.75†

|

1,4 < 2,3 |

|

Altruism and service |

2.81 ± 1.03 |

3.43 ± 1.10 |

3.60 ± 1.24 |

2.93 ± 1.11 |

22.91†

|

1,4 < 2,3 |

|

Critical thinking and problem-solving skills |

3.32 ± 1.19 |

4.06 ± 1.22 |

4.16 ± 1.14 |

3.37 ± 1.12 |

27.10†

|

1,4 < 2,3 |

|

Ability to control one's behavior and emotions |

3.47 ± 1.06 |

3.81 ± 1.11 |

4.23 ± 1.12 |

3.21 ± 1.12 |

28.43†

|

1,4 < 2 < 3 |

|

A capacity to handle stress |

3.67 ± 1.24 |

3.97 ± 1.76 |

4.21 ± 1.22 |

3.14 ± 1.16 |

16.67†

|

4 < 1 < 2,3 |

|

Manners |

3.16 ± 1.15 |

3.74 ± 1.15 |

4.27 ± 1.21 |

2.94 ± 1.21 |

48.63†

|

1,4 < 2 < 3 |

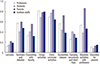

Effective methods for teaching humanism education

In all sub-groups, the most frequently chosen option was "activities beyond the required classes (sports, choir, music appreciation, art and other creative activities)," followed by "small group activities, humanities classes and debates," and "regular volunteer activities with professors." The least frequently chosen options were "parents' education" and "lectures" (

Fig. 1).

Fig. 1

Mean scores on perceived effectiveness of teaching methods for humanism education in a medical school. Question 3 was a multiple-choice question that asked, "Select at least three effective methods for teaching humanistic competencies."

Other opinions in the form of short answers addressed issues related to improving curricula: extracurricular activities (discussing problems with friends, watching movies, experiencing other jobs or majors, debating actual cases, and mentoring programs), launching courses related to humanism, and eliminating a school culture focused on grades. The following were also mentioned: reinforcing parental discipline, increasing professors' humanism education, and increasing the frequency of humanism assessments during interviews for entering medical school.

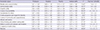

The expected effectiveness of humanism education, the need for it, and methods of implementation

Regarding Questions 4-7, which asked participants about the effectiveness of humanism education, the participants estimated that humanism education would be mildly to moderately effective (in the order of the parents, professors, institute staff, and students). With regard to how necessary it is for medical schools to offer humanism education and how much participants supported colleges offering it, the mean score was the highest among the parents, followed by the institute staff, the professors, and the students.

With regard to the level of support for colleges offering humanism education as a credited course, the mean score was the highest among the institute staff, followed by the parents, professors, and students. When comparing the school staff with the parents, the professors and students expressed a rather passive stance toward implementing humanism education in colleges. Students were more opposed than any other group to selecting humanism education as a credited course (

Table 4).

Table 4

The rating scores of the effectiveness and necessity for humanism education in medical school (mean ± SD)

|

Education parameters |

Professors |

Students |

Parents |

Institute staffs |

Total |

|

The effectiveness of humanism education |

2.33 ± 0.65 |

2.01 ± 0.83 |

2.84 ± 0.65 |

2.43 ± 0.58 |

2.28 ± 0.81 |

|

The need for humanism education |

3.06 ± 0.79 |

2.48 ± 1.01 |

3.40 ± 0.64 |

3.30 ± 0.69 |

2.86 ± 0.97 |

|

The degree of support for schools providing humanism education |

3.05 ± 0.83 |

2.46 ± 1.07 |

3.48 ± 0.66 |

3.37 ± 0.70 |

2.88 ± 1.02 |

|

The degree of support for schools selecting humanism education as a credited course |

2.55 ± 1.12 |

1.81 ± 1.24 |

3.01 ± 0.99 |

3.08 ± 0.76 |

2.38 ± 1.24 |

Methods for assessing performance in humanism education courses

In terms of gauging students' performance in humanism education courses, most participants responded that they preferred a "pass/fail" method based on their rate of participation, and they desire hands-on programs rather than simple lectures. However, many participants opposed the idea of evaluations, because accuracy and fairness are hard to verify. Many students especially opposed introducing humanism education as a regular course subject, and grading students based on a relative evaluation. Instead, they suggested team activities, small group activities with professors, anonymous peer evaluations, and submitting essays. Most sub-groups suggested submitting term papers or essays, peer assessments, evaluations by the institute (by patients or medical staff), and humanism-related tests.

DISCUSSION

The authors surveyed medical students, professors, university staff, parents, and medical staff that doctors work with (such as nurses, administrative staff, and laboratory technicians) on essential humanistic competencies that medical students should have, and on teaching methods that will effectively develop such attributes. Since medical treatment is a doctor-patient interaction based on respect, it is crucial for medical students to learn about and experience humanistic values in medical school.

As essential values that directly affect the treatment of patients, previous studies have focused on a sense of ethics, an honesty, and a sense of accountability; most medical schools and intern programs share similar values (

10). In the workplace, where there is a lot of stress due to heavy workloads, it is necessary to interact with diverse people and consider potential risks and accountability to prevent doctors from experiencing burnout, and helping them maintain a life purpose and sense of satisfaction from their jobs. It seems that studying the humanities in medicine leads to "good" and "happy doctors" (

2).

According to the results, all groups (professors, students, parents, and institute staff) chose "morality and a sense of ethics" as the most important trait. In addition, a "sense of accountability," "communication skills," and "empathic ability" were selected as essential qualities. According to the evaluation on the extent to which students possess each quality, participants believed students had a high "sense of accountability," whereas participants thought students had low "empathic ability," "communicate," or "collaborate with others". There was a difference among the groups in the results. The professor and school staff groups scored meaningfully lower than student and parent groups. This is believed to be due to the fact that professors and school staff, within a real-life school or hospital setting, have a higher evaluation standard for the students they view as future doctors.

This shows the need to expand humanism education, through which medical students can learn to empathize, communicate, mindfulness and tolerance, and a sense of community and cooperation. These values, which medical students can experience and practice by interacting with other people, require specific, observable actions such as showing respect, eliciting emotions and responding to them, and communicating effectively (

11).

It is thus necessary to introduce more diverse teaching methods, rather than uniform, passive lectures, so that students can effectively develop each humanistic competency. In terms of effective teaching methods, all sub-groups preferred experience-based teaching methods, rather than classroom lectures. They preferred extracurricular activities (sports, music, art, or other creative activities) and small group activities the most; they also positively assessed humanities classes, debates, and volunteer service with professors.

Although there is no consensus as to the best method for teaching professionalism in medical education, previous studies have reported role modeling and mentoring to be effective (

12), because they allow students to communicate and interact with patients and peers in many different ways in a safe environment with fewer risks (

13). Besides conventional methods such as lectures, simulation or role-playing, which both school staff and students prefer, are expected to increase the educational effect of humanism education when used during debates or small group activities.

With regard to the speculated effect of humanism education and the awareness of the need for colleges to offer it, all sub-groups had a positive response. However, in terms of introducing humanism education as a credited course, most parents and school staff supported the idea, whereas the professors expressed a relatively passive stance; there was stronger opposition from student groups. This passive stance is believed to be due to the fact that the professor group, although agreeing with the need for humanistic education, would feel burdened by the increase in workload, and the student group would feel burdened by the lectures and evaluations. Some professors even showed skepticism towards the idea of "educating" one's character in school. Additionally, it is thought that this judgment may have been affected by the perception that there is still a lack of a curriculum and an institutional and human resource infrastructure to provide humanistic education in schools. On the other hand, as future colleagues who may work together, the staff believe that there is a need to increase students' communication skills through education (the staff group believes that communication ability is the second most important attribute after ethics). Furthermore, parents desire an increased level of education and more activities between the students and the professors. Thus, the results reflect the different requirements of each group.

Although all groups were aware of the need for humanism education, it appears that the workload (study load) or the burden of assessing performance was an obstacle for them to willingly participate in humanism education courses. Hence, it seems best to introduce a core humanism education program into medical school curricula in phases, and to adopt a horizontal evaluation by peers or a "pass/fail" method based on the rate of participation, as opposed to a subjective assessment by faculty, which can be stressful.

This study has the following limitations. Firstly, the groups that participated were limited to the staff and parents of a specific medical school; thus, the results cannot represent all medical schools in Korea. There are 41 medical colleges and schools in the country. Each school has different goals and educational features based on various criteria such as the founder, location, the quota for the number of students and staff, and whether it has a research hospital. This leads to a disparity in criteria for core humanistic competencies or preferred teaching methods. Secondly, among the essential humanistic competencies that the authors suggested, some abstract traits (e.g., altruism) can be interpreted differently based on participants' subjective opinions. In future studies, we can mitigate this limitation by giving clearer operational definitions to the presented concepts in multiple-choice questions. Finally, due to the unavailability of standardized survey instruments related to the evaluation of core humanistic competencies in Korea, the authors created and used this survey instrument upon completing theoretical reviews of common humanistic competencies and values, and validity verification for the information provided by 10 medical school professors that provide student guidance. The validity and reliability of the survey instrument could not be verified due to the short duration of the study; therefore, there are limitations to the generalization of the survey results, and the questionnaire needs to be revised for further studies.

The conclusion and significance of this study can be summarized as follows. Current medical students have a strong degree of morality and sense of ethics, as well as a sense of accountability. In comparison, they lack some essential humanistic competencies, such as empathy and communication skills. Therefore, they should receive complementary humanism education. Regarding teaching methods for humanism education, it is expected that the field will develop effectively through experience-based activities, which medical school constituents prefer; these include debates, as well as extracurricular and small group activities.

In terms of essential elements for successfully operating a humanism education program, previous studies (

1213) mentioned the training and participation of faculty members in educational and clinical fields, as well as creating an organization's culture and environment. In order to reap more comprehensive and lasting effects of humanism education courses in medical school, it is necessary to conduct faculty workshops, launch a committee to monitor a humanism education program, and continuously strive to develop this program.

PDF

PDF ePub

ePub Citation

Citation Print

Print

XML Download

XML Download