Abstract

Recently in Korea, the commercialization of health services has come to the fore, and the issue of egalitarianism/universal coverage in health is a matter for debate. This study explored the extent of Korean citizen's preference for egalitarian health policies focusing on the provision of health care service, financing and related factors. The data came from the 2011 Korean General Social Survey (KGSS) and the International Social Survey Program (ISSP). The preference for an egalitarian health policy (dependent variable) was divided into a preference for an egalitarian health services provision (ES) and a willingness to contribute (WC) to it. Each index was linearly regressed with demographic factors, socioeconomic status, ideology, and health-related factors. ES was significantly associated with an individual's egalitarianism and political liberalism, having illness/disability, having no additional private health insurance, and their perception of health insurance coverage. WC was associated with age, sex, household income, education, egalitarianism, and their perception of health insurance coverage. There were evidently different factors between ES and WC, mainly socioeconomic factors. WC was strongly influenced by socioeconomic status, whereas ES seemed to be linked more closely to economic affordability. Moreover, the results showed that Korean citizens prefer ES but do not like WC. These results deserve great attention, and the authorities should keep it in perspective. If the government wants to make a successful attempt to change the healthcare system through public policy, it will need to take public preferences into account.

It is widely accepted that one of the objectives of government policy with respect to health is to maximize the average population health. At the same time, equality in the distribution of health is another principal objective with the recognition that health is a fundamental right of every human (1, 2, 3). The World Health Organization (WHO) emphasizes that universal coverage is the best way to attain that human right, and universal health coverage ensures that all people obtain the health services they need without discrimination based on race, religion, political beliefs, or economic and social conditions. Thus, universal health coverage is egalitarian (3). In many countries, governments hold egalitarian health policies as a primary goal, and these policies have been established to reduce socioeconomic inequality of health (3, 4). Indeed, egalitarian health policies have led to improvements in population health in the OECD member nations, as measured by mortality and life expectancy at birth (5).

Nevertheless, a debate on commercializing health services is revolving around controversial issues of promoting efficiency in the healthcare system and creating national wealth. The government of Korea recently announced an activation plan for accelerating the commercialization of health services, i.e., establishing for-profit hospitals and privatizing hospitals into business entities. Soon after, that plan confronted strong opposition from Korean citizens. As we have seen in various situations, such as that in the US, commercialized systems lag behind universal coverage systems in terms of health outcomes among citizens, despite spending vast portions of their economy on healthcare services (6, 7). Furthermore, there is an ideological question of whether healthcare is a fundamental human right or a commercial activity. Since the 1970s, Korea has had an egalitarian health policy with strong government intervention for finance and coverage (8), so that a single insurer was set up, i.e. National Health Insurance (NHI) (9, 10). As a result, the government achieved almost 100% universal coverage through the NHI, however, more than 90% of the services are provided by the private sector. With respect to the public debate on health policy reform in Korea, it is meaningful to examine the extent to which lay people prefer an egalitarian health policy and compare it to the same in other nations. Moreover, given that public preferences for an egalitarian health policy play a key role in population health and in health policy outcomes (5, 11), it is also necessary to investigate its determinants.

Up to date, few studies (only in Europe and the US) have been conducted on this topic, and they have identified that 69%-75% of citizens prefer and support an egalitarian health policy (1, 2, 4). However, little is known about the underlying mechanisms of those preferences for an egalitarian health policy. Previous studies focused on demographic, ideological (e.g., egalitarianism, political orientation, etc.), socioeconomic (e.g., income, education, employment, etc.) factors (1, 2, 4, 12, 13, 14), so they did not address the associations between preferences for an egalitarian health policy and health-related factors, such as having an illness/disability and being satisfied with health insurance coverage. In particular, previous studies did not distinguish between the preference for an egalitarian health service provision and willingness to contribute to it. Given that national health expenditures are increasing sharply along with mounting demands for health services despite the recession, important policy implications can be drawn from a careful comparison of these two dimensions of preference. For example, if a preference for an egalitarian health service provision outweighs the willingness to contribute, a nation might need to be cautious and should consider the sustainability/expansion of an egalitarian health policy.

In this vein, this present study aims to evaluate the extent to which Korean citizens prefer an egalitarian health policy focused on the provision of health care service and financing, and compare it to other countries. Then, we explored factors associated with preferences for an egalitarian health policy in two dimensions, i.e., preference for an egalitarian health service provision and the willingness to contribute to it. There are several topics in the area of health policy. Those are legislation, financing, access to care, delivery system, quality of care, health equity and so on. Among them, this study covers the area of service provision and financing.

Data used in this study came from the 2011 Korean General Social Survey (KGSS) data archive. KGSS shares a module with the International Social Survey Program (ISSP) and presents nationally representative data based on multi-stage area probability sampling (18). The topics of the 2011 survey included ideology, demographic factors, socioeconomic status, and health-related variables. The sample size of the 2011 data was 1,535. We used the 2011 ISSP raw data to explore the extent of preferences for an egalitarian health policy in other nations and compared it with that of Korean citizens. ISSP has been a continuous annual cross-national collaboration program of surveys covering topics important to social science research since 1985. The questionnaire was originally drafted in English and was translated to other languages for use in all member nations. It includes data from 29 member nations (website: http://www.issp.org/).

The dependent variable was the preference for an egalitarian health policy. An egalitarian health policy is "a policy in which everyone receives a certain level of health benefits regardless of their citizenship/demographic/socioeconomic status (13)." Two indices were created to measure aspects of preference for an egalitarian health policy: the preference for an egalitarian health service provision (ES) and the willingness to contribute (WC) to it.

The ES was obtained through the 2011 KGSS question "How much is it fair or unfair that high-income earners receive better health services than do their low-income counterparts?" The answers were coded as 1, "very fair;" 2, "fair;" 3, "neither fair nor unfair;" 4, "unfair;" and 5, "very unfair." These answers reflect whether the respondent has a positive view toward an egalitarian health service provision. The WC, another dependent variable, was obtained by asking the question "What intention do you have to pay more taxes to improve health services for all people in Korea?" The responses were coded as 1, "none;" 2, "little;" 3, "neither too little nor too much;" 4, "much;" and 5, "very much." These answers reflect the intention to pay more taxes to improve health services for all people.

Three indicators were constructed to capture egalitarianism ("a view from which everyone should enjoy basic economic and sociopolitical rights regardless of their demographic/socioeconomic status (13)." The first one was a positive view that the government should treat everyone equally regardless of his/her status (scaled 1-7, where 7=most agree), the second was a positive view for an egalitarian distribution of income by the government (scaled 1-5, where 5=most agree), and the third was a positive view for an increased provision of welfare by the government (scaled 1-10, where 10=most agree). The answers were standardized based on 5 points, and summed over the three items, with a minimum score of 3 and a maximum of 15.

Three dummy variables were produced for political orientation, such as "1"=conservative, "2"=midway, and "3"=liberal.

The demographic factors included sex and age. Four education dummies indicating socioeconomic status were constructed for elementary school (0-6 yr of education: reference group), junior high school (7-9 yr of education), senior high school (10-12 yr of education), and postsecondary school (13 or more years of education). Similarly, average monthly household income was changed to a quartile index, and employment status was included as a socioeconomic status factor. Finally, health-related factors included having an illness/disability, having health insurance, and the perception of health insurance coverage. The health insurance variable was presented as "1" for having NHI only, without any complementary private health insurance, and "0" for having additional private health insurance. A dummy variable was introduced for the perception of health insurance coverage, "1", "not well covered" and "0", "well covered".

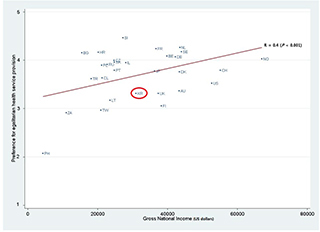

A bivariate analysis including the t-test and ANOVA were conducted to explore the relationship between independent variables and the two preferences for an egalitarian health policy. Figures were prepared to show the level of each nation's egalitarian health policy preference and the correlation between preference for an egalitarian health policy and the Gross National Income (GNI) of the nation. Each index was linearly regressed on demographic factors, socioeconomic status, ideology, and health-related factors to detect significant differences. We also verified linearity, normality, homoscedasticity, and independence for linear regression, and our data met these assumptions.

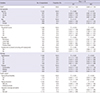

The distribution of responses shown in Table 1 reveals that Korean citizen's preference for the two aspects of egalitarian health policy do not move in tandem. The average ES score was 3.311, whereas that of WC was 2.844. Given a cut-off point is 3.0, the proportion of citizens who preferred egalitarian health policy in the ES was higher, but not in the WC. In other words, Korean citizens prefer ES more than WC.

Fig. 1 and Fig. 2 show the extent to which Koreans prefer ES and WC compared to those of other countries in the ISSP data. The results show that the Korean's ES level was relatively lower than that of citizens from other nations (mean of all countries =3.696), whereas WC was relatively higher (mean of all countries=2.623). In addition, an increase in GNI was positively correlated with the preference level for both aspects, i.e. ES (r=0.4, P<0.001) and WC (r=0.3, P<0.001).

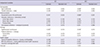

Table 2 presents the results of an OLS regression on the two aspects of preferences for an egalitarian health policy. ES was significantly associated with an individual's egalitarianism (P< 0.01) and political liberalism (P<0.05), having illness/disability (P<0.01), NHI without additional private health insurance (P< 0.05), and perception of health insurance coverage (P<0.01), whereas WC was associated with age (P<0.05), sex (P<0.01), household income (P<0.05), education (P<0.05), egalitarianism (P<0.01), and perception of health insurance coverage (P< 0.01).

In this study, the score of a Korean citizen's preference for ES was more than 3.0 (cut-off point), whereas the WC score was less than the cut-off point, indicating that Korean lay people prefer an egalitarian health service provision but do not want to contribute to it, which is a similar phenomenon with other countries. This result demonstrates that different health policies are essential for different dimensions of health policy preference, and an accurate investigation may require precisely dividing this concept and rigorously constructing indices. However, there is also a possibility that the reason why the different aspect appear is due to different questionnaire. The question of ES was intended for unspecified individuals on the provision of health services, whereas WC was very close to one's intention to contribute. Compared with other nations, the ES level of Koreans was relatively lower than that of other nations (only five nations including the Philippines and South Africa had a lower score than that of Korea), and the GNI of nations was positively correlated with the level of preference in both aspects. These results deserve great attention because the ES and WC levels are likely to increase with the growing GNI in Korea also. Thus, the authorities need to keep it in perspective, and more studies are necessary.

We explored factors associated with the preference for an egalitarian health policy using ES and WC to address what factors make people prefer an egalitarian health policy. First, ES was influenced by an individual's ideology and health-related factors, but not by demographic or socioeconomic status, as previous studies have shown (1, 4, 14). With regard to demographic and socioeconomic status, it seems that Korean lay people also think universal and egalitarian health services should be provided, as shown in other nations, regardless of their demographic and socioeconomic status (1, 4, 14). Moreover, the high social class in Korea (highly educated, rich, and employed) differs very little from the low social class in terms of ES (so-called "classlessness" in egalitarian health service provision) (15). As Bambra et al. (16) and Shin (17) argue, this quality may stem, in part, from "medicalization" in these nations, which is a process in which the general public leaves health issues mainly to healthcare professionals and these healthcare professionals share a consensus on the egalitarian distribution of health services represented by the Hippocratic Oath. However, ideological variables had a positive impact on ES. This result is consistent with previous studies in Europe and the US reporting that ES may be influenced by an individual's ideological beliefs, such as egalitarianism and political liberalism (1, 12, 13, 14). As argued in those studies, it seems that the portion of the public with a strong egalitarian ideology has positive attitudes toward an egalitarian policy, as most people tend to keep their beliefs and attitudes internally consistent. Those studies also show that those who support political liberalism have more sympathy towards an egalitarian policy. Finally, in this study, physical health problems, no supplemental private health insurance, and a negative perception with respect to health insurance coverage were influential in a stronger ES. This result can be explained by the self-interest theory. According to the self-interest theory, those who stand in need of benefits from a specific policy or are at risk of becoming beneficiaries are more likely to support that policy (1, 2, 4, 12, 13, 14).

With respect to WC, interestingly, this study shows that "classlessness", which indicates a willingness to benefit from an egalitarian health policy regardless of social class, is superseded by individual demographic and socioeconomic status for WC and the egalitarian health service provision. In this study, women or the lower social class (e.g., poor or uneducated) had a weaker WC than that of men or the higher social class (e.g., rich or educated). As for sex, it can be explained by the fact that women have traditionally performed the majority of unpaid work, such as housework or elderly care in the home. In other words, they are more likely to be economically vulnerable than men. Similarly, the lower social class cannot afford to pay for an egalitarian health service provision. In other words, WC is strongly influenced by socioeconomic status in sharp contrast to ES. WC was linked closely to the economic affordability of contributing to an egalitarian health policy. As for ideology, it corresponded with the results of ES that showed a stronger egalitarian ideology was closely related to a positive attitude toward an egalitarian policy. This feature of ES can similarly be applied to WC. Finally, poor health had a negative effect on WC in contrast to ES. Unexpectedly, a negative perception to health insurance coverage had an adverse effect on WC, and it seems that those who are not satisfied with social health insurance coverage would not want to pay more taxes for that.

In conclusion, this study shows different aspects of the preference for an egalitarian health policy. We demonstrated that there are evidently different factors between ES and WC; WC is strongly influenced by socioeconomic status in sharp contrast to ES, and it seems to be linked closely to economic affordability. If the government wants to make a successful attempt to change the healthcare system through public policy, it will need to take public preferences into account. Health is a fundamental right of the citizens, not simply a form of assistance. However, given that those who have poor health-related factors would like to benefit more from but contribute less to egalitarian health service provisions, Korea might need to be cautious with respect to the sustainability/expansion of an egalitarian health policy. As providing egalitarian health services should be accompanied by proper contributions to it, there will be no benefit if no contributions are made.

This study has several limitations. First, our results cannot be generalized to comprehensive egalitarian health policy because we only focused on individual's attitudes about the health service provision and financing. Thus, the results should be interpreted cautiously. Second, this study did not include all variables reported as factors related to the preference for an egalitarian health policy, such as personal potential to benefit from the policy. Such variables should be included in further studies. Third, our results may not fully explain the causal relationship due to the cross-sectional study design. Fourth, the scope of this study is limited to Korea, so a comparative analysis across East Asia would expand knowledge further.

In spite of these limitations, this study is important, as it is the first to explore factors associated with a preference for an egalitarian health policy separated into two dimensions: preference for egalitarian health services and a willingness to contribute to it. This study refined the definition and measurement of health policy preferences, and will help understand the relationship to ideological, demographic, socioeconomic, or health-related determinants in Korea, a nation that is undergoing rapid political and socioeconomic transformation.

Figures and Tables

Fig. 1

The level of preference for an egalitarian health service provision according to Gross National Income (GNI, US Dollars). AU, Australia; BE, Belgium; BG, Bulgaria; CL, Chile; TW, Taiwan; HR, Croatia; CZ, Czech Republic; DK, Denmark; FI, Finland; FR, France; DE, Germany; IL, Israel; JP, Japan; KR, Korea; LT, Lithuania; NL, the Netherlands; NO, Norway; PH, the Philippines; PL, Poland; PT, Portugal; RU, Russia; SK, Slovak Republic; SI, Slovenia; ZA, South Africa; SE, Sweden; CH, Switzerland; TR, Turkey; UK, United Kingdom; US, United States.

Fig. 2

The level of willingness to contribute to an egalitarian health service provision according to Gross National Income (GNI, US Dollars). AU, Australia; BE, Belgium; BG, Bulgaria; CL, Chile; TW, Taiwan; HR, Croatia; CZ, Czech Republic; DK, Denmark; FI, Finland; FR, France; DE, Germany; IL, Israel; JP, Japan; KR, Korea; LT, Lithuania; NL, the Netherlands; NO, Norway; PH, the Philippines; PL, Poland; PT, Portugal; RU, Russia; SK, Slovak Republic; SI, Slovenia; ZA, South Africa; SE, Sweden; CH, Switzerland; TR, Turkey; UK, United Kingdom; US, United States.

Table 1

Distributions of respondents for each variable with a test for equal means

Table 2

Ordinary least squares regression results on preference for an egalitarian health policy in Korea

References

1. Lynch J, Gollust SE. Playing fair: fairness beliefs and health policy preferences in the United States? J Health Polit Policy Law. 2010; 35:849–887.

2. Abasolo I, Tsuchiya A. Understanding preference for egalitarian policies in health: are age and sex determinants? Appl Econ. 2008; 40:2451–2461.

3. Evans DB, Etienne C. Health systems financing and the path to universal coverage. Bull World Health Organ. 2010; 88:402.

4. Abásolo I, Tsuchiya A. Egalitarianism and altruism in health: some evidence of their relationship. Int J Equity Health. 2014; 13:13.

5. Navarro V, Muntaner C, Borrell C, Benach J, Quiroga A, Rodríguez-Sanz M, Vergés N, Pasarín MI. Politics and health outcomes. Lancet. 2006; 368:1033–1037.

6. Schoen C, Davis K, How SK, Schoenbaum SC. U.S. health system performance: a national scorecard. Health Aff (Millwood). 2006; 25:w457–w475.

7. Bezruchka S. The hurrider I go the behinder I get: the deteriorating international ranking of U.S. health status. Annu Rev Public Health. 2012; 33:157–173.

8. Amsden AH. Why isn't the whole world experimenting with the East Asian model to develop?: Review of the East Asian miracle. World Dev. 1994; 22:627–633.

9. Kim DS. Introduction: health of the health care system in Korea. Soc Work Public Health. 2010; 25:127–141.

10. Kang MS, Jang HS, Lee M, Park EC. Sustainability of Korean National Health Insurance. J Korean Med Sci. 2012; 27:S21–S24.

11. Monroe AD. Public opinion and public policy, 1980-1993. Public Opin Q. 1998; 6–28.

12. Koch JW. Political rhetoric and political persuasion: the changing structure of citizens' preferences on health insurance during policy debate. Public Opin Q. 1998; 209–229.

13. Blekesaune M, Quadagno J. Public attitudes toward welfare state policies a comparative analysis of 24 nations. Eur Sociol Rev. 2003; 19:415–427.

14. Feldman S, Steenbergen MR. The humanitarian foundation of public support for social welfare. Am J Polit Sci. 2001; 658–677.

15. Kim YS. Welfare politics and welfare state: problems and reform issues from the institutional view. In : . Health policy and politics: health meets politics. Seoul: Korean Academy of Critical Health Policy;2012. p. 129–154.

16. Bambra C, Fox D, Scott-Samuel A. Towards a politics of health. Health Promot Int. 2005; 20:187–193.

17. Shin YJ. Breaking the myths of health and politics. In : . Health policy and politics: health meets politics. Seoul: Korean Academy of Critical Health Policy;2012. p. 155–201.

18. Kim SW. A comparison of the characteristics of general social surveys in east asia. Sungkyun J East Asian Stud. 2004; 4:137–154.

PDF

PDF ePub

ePub Citation

Citation Print

Print

XML Download

XML Download