Abstract

Congenital extrahepatic portocaval shunt (CEPS) is a rare anomaly of the mesenteric vasculature in which the intestinal and splenic venous drainage bypasses the liver and drains directly into the inferior vena cava, the left hepatic vein or the left renal vein. This uncommon disease is frequently associated with other malformations and mainly affects females. Here we report a case of pulmonary arterial hypertension associated with CEPS (Abernethy type 1b shunt) in a 20-yr-old man who was incidentally diagnosed during evaluation of multiple nodules of the liver. The patient was treated by inhalation of iloprost (40 µg/day) with improved condition and walking test. Physicians should note that congenital portocaval shunt may cause pulmonary hypertension.

Congenital extrahepatic portocaval shunt (CEPS) is a congenital anomaly observed predominantly in females in which the splanchnic blood bypasses the liver and drains directly into the inferior vena cava (IVC). After the first description of this entity by Abernethy in 1793, fewer than 30 cases of CEPS have been reported (1). Pulmonary hypertension related to CEPS is an extremely rare condition: to date, only a few cases have been reported in the medical literature (2, 3). Here we present a case of CEPS in an adult male, which has not been described previously.

In October 2012, a 20-yr-old male was referred to our department with pulmonary hypertension of unknown etiology. He underwent surgical closure of ventricular septal defect (VSD) at 10 months of age. Eleven months before admission, the patient underwent laparoscopic appendectomy at another hospital. During the preoperative evaluation, screening abdominal ultrasound (US) showed multiple liver masses, and transthoracic Doppler echocardiography (TTE) showed pulmonary hypertension of unknown origin.

On admission, the patient had mild exertional dyspnea (New York Heart Association, NYHA class II). Physical examination revealed pectus excavatum but was otherwise unremarkable. The electrocardiogram demonstrated regular sinus rhythm with right bundle branch block (RBBB), and the chest X-ray showed mild cardiomegaly and increased pulmonary vascularity with bulged pulmonary conus (Fig. 1). At admission, the patient's laboratory values were within normal limits except for slightly reduced serum total protein (6.3 g/dL; reference range, 6.6-8.3) and mildly elevated direct bilirubin (0.53 mg/dL; reference range, 0.13-0.47) and blood ammonia (105 µg/dL; reference range, 20-80). Serologic markers for hepatits B and C virus and for AFP and CA-19 were negative.

TTE showed a significantly dilated right ventricle (RV) chamber with a D-shaped left ventricle (LV). The LV chamber was mildly dilated, but the LV ejection fraction was normal. The estimated RV systolic pressure (RVSP), calculated as the maximal velocity of tricuspid regurgitation (TR Vmax), was 64 mmHg, which indicated moderate pulmonary hypertension (Fig. 2). We found no definite shunt flow through the inter-ventricular or inter-atrial septum and main pulmonary artery. In addition, there was no evidence of pulmonary thromboembolism or pericardial effusion. These findings were confirmed by transesophageal echocardiography (TEE).

Cardiac catheterization was performed to confirm the diagnosis and to classify the pulmonary hypertension based on the Dana Point classification recommended by the World Health Organization (WHO) (4, 5). Right catheterization, performed with a Cournand catheter, showed a pulmonary capillary wedge pressure (PCWP) of 7 mmHg, mean pulmonary arterial pressure (mPAP) of 44 mmHg (Fig. 3), pulmonary vascular resistance (PVR) of 608 dyn·s·cm-5 and a cardiac index (CI) of 2.89 L/min per m2. Consequently, pulmonary arterial hypertension (group 1 pulmonary arterial hypertension) was diagnosed by right heart catheterization (RHC). Interestingly, significant oxygen step-up was observed between the inferior vena cava (IVC) and the low level of right atrium (RA) during O2 saturation analysis of the right heart. This findings suggested significant arterial blood shunt in this area.

Abdominal computed tomography (CT) and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) were performed to further evaluate the multiple liver masses that were found incidentally at the patient's local hospital. CT showed ill-defined low-density nodular lesions in the bilateral hemiliver. These lesions exhibited hyperintensity on T1-weighted MR images, with the larger ones containing a central scar with a high signal intensity on T2-weighted MRI images and a low signal intensity on T1-weighted MR images (Fig. 4). Based on the CT and MR imaging results, initially we thought that the pulmonary arterial hypertension was caused by portal hypertension, which is known as portopulmonary hypertension associated with nodules of liver cirrhosis (LC). A percutaneous liver biopsy was performed under US guidance for histological diagnosis, which was multifocal nodular regenerative hyperplasia with no evidence of LC. Therefore, CT angiography and portal venography were performed to investigate whether intra- or extra-cardiac shunt was present and also to determine the anatomical relationship between the portal venous system and the right heart; both can cause pulmonary arterial hypertension.

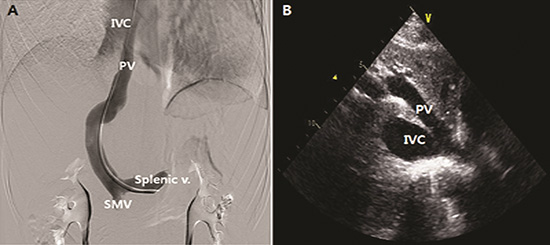

CT angiography demonstrated the presence of a portocaval shunt in which the left portal vein (PV) and left hepatic vein joined and drained directly into the suprahepatic IVC without passing through the liver (Fig. 5). Portal venography revealed abnormal communication between the left PV and IVC with obliteration of the right PV (Abernethy type 1b) (Fig. 6A). The main PV and hepatic venous wedge pressure were both 6 mmHg. The superior mesenteric and splenic venous pressures were 6 mmHg and 9 mmHg, respectively. In addition, we reexamined the TTE that was not able to detect this communication at first, in which type 1 CEPS could be clearly visualized on the subcostal window (Fig. 6B).

We confirmed the diagnosis as a pulmonary arterial hypertension caused by CEPS (Abernethy type 1b) and multifocal nodular regenerative hyperplasia of the liver. However, there was no deinite evidence of other cardiac, gastrointestinal or genitourinary anomalies that are also known to be associated with type 1 CEPS. The patient began inhalation of iloprost (40 µg/day) and was taught to use a nebulizer. The patient's condition improved and he was discharged on day 7. At a 5-month follow-up appointment, his 6-min walking test improved from 380 m to 525 m, and TTE showed a reduction in RVSP from 64 mmHg to 49 mmHg.

Congenital extrahepatic portocaval shunts, also known as Abernethy malformations, are classified into 2 types based on the presence or absence of portal blood flow within the hepatic parenchyma. The first type is congenital atresia of the portal vein (end-to-side anastomosis, an Abernethy type 1 shunt), in which the superior mesenteric and splenic veins can join the IVC separately (type 1a) or as a confluence (type 1b). The second type other is hypoplasia of the portal vein with a resultant partial portocaval shunt (side-to-side anastomosis, an Abernethy type 2 shunt). Each type of shunt is associated with unique clinical manifestations: A type 1 shunt, as was present in this patient as a type 1b shunt, is more common in females and is often complicated by congenital cardiac defects, hepatic masses, gastrointestinal and vascular anomalies (1, 6). However, a type 2 shunt is more common in males and is rarely associated with other malformations.

Pulmonary hypertension is well recognized as a complication of portal hypertension in chronic liver diseases (7, 8), but only a few cases of pulmonary hypertension have been reported that are the result of congenital extrahepatic portocaval shunt (type 1b) (2, 3). Notably, there are no previous reports of an adult male with VSD and asymptomatic multiple regenerative nodules of the liver. This patient described here was diagnosed after observation of multifocal nodular regenerative hyperplasia of the liver, and the classic symptoms related to portal hypertension were entirely absent. In the present case, it seems that gut-derived vasoactive substances, such as serotonin (5-hydroxytryptamine [5-HT]), histamine, estrogen, glucagon and endotoxin, all of which are normally metabolized in the liver, bypassed hepatic detoxification via the portocaval shunt leading to pulmonary hypertension by inducing a long-standing pulmonary vasoconstriction (9, 10, 11). Furthermore, the decrease in RVSP after iloprost treatment demonstrates that vasoconstriction played an important role in this patient.

In the reported patient, the initial impression was secondary pulmonary hypertension caused by VSD because of his previous history of surgical closure of VSD. However, there was no evidence of associated congenital cardiac defects such as, VSD, atrial septal defect (ASD), or patent ductus arteriosus (PDA). In addition, because the patient had multiple liver nodules, an erroneous diagnosis of portopulmonary hypertension was made during the evaluation. Although rare, these regenerative nodules have been reported to be associated with congenital portocaval shunts, which is why we performed CT angiography and portal venography in this patient (12). Physicians should note that congenital portocaval shunt may cause pulmonary hypertension underlying multifocal nodular regenerative lesions of the liver without portal hypertension. Furthermore, if pulmonary hypertension of unknown origin is found, despite prior correction of congenital cardiac anomalies, clinicians should consider all possible causes of secondary pulmonary hypertension.

Figures and Tables

Fig. 1

Chest X-ray showed cardiomegaly and increased vascularity of the proximal portion of both pulmonary arteries.

Fig. 2

Two-dimensional echocardiography, showing D-shpaed left ventricle during diastole phase in parasternal short axis view (arrowhead) (A) and transthoracic Doppler echocardiography, showing tricuspid regurgitation with maximal pressure gradient (54.8 mmHg) (B).

Fig. 3

Right heart catheterization, showing the systolic pulmonary artery pressure was 52-63 mmHg, and the mean pulmonary artery pressure was 44 mmHg (A). The estimated mean pulmonary capillary wedge pressure was 7 mmHg (B).

Fig. 4

Cardiac magnetic resonance imaging, showing multiple hyperintense masses adjacent to the heaptic parenchyma. There was a central stellate scar that was hypointense on the T1 images (arrowheads) (A) and hyperintense on the T2 images (arrows) (B).

References

1. Howard ER, Davenport M. Congenital extrahepatic portocaval shunts: the Abernethy malformation. J Pediatr Surg. 1997; 32:494–497.

2. Ohno T, Muneuchi J, Ihara K, Yuge T, Kanaya Y, Yamaki S, Hara T. Pulmonary hypertension in patients with congenital portosystemic venous shunt: a previously unrecognized association. Pediatrics. 2008; 121:e892–e899.

3. Imamura H, Momose T, Kitabayashi H, Takahashi W, Yazaki Y, Takenaka H, Isobe M, Sekiguchi M, Kubo K. Pulmonary hypertension as a result of asymptomatic portosystemic shunt. Jpn Circ J. 2000; 64:471–473.

4. Badesch DB, Champion HC, Sanchez MA, Hoeper MM, Loyd JE, Manes A, McGoon M, Naeije R, Olschewski H, Oudiz RJ, et al. Diagnosis and assessment of pulmonary arterial hypertension. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2009; 54:S55–S66.

5. Simonneau G, Robbins IM, Beghetti M, Channick RN, Delcroix M, Denton CP, Elliott CG, Gaine SP, Gladwin MT, Jing ZC, et al. Updated clinical classification of pulmonary hypertension. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2009; 54:S43–S54.

6. Morgan G, Superina R. Congenital absence of the portal vein: two cases and a proposed classification system for portasystemic vascular anomalies. J Pediatr Surg. 1994; 29:1239–1241.

7. Mandell MS, Groves BM. Pulmonary hypertension in chronic liver disease. Clin Chest Med. 1996; 17:17–33.

8. Umeda N, Kamath PS. Hepatopulmonary syndrome and portopulmonary hypertension. Hepatol Res. 2009; 39:1020–1022.

9. Liehr H, Grün M, Thiel H, Brunswig D, Rasenack U. Endotoxin-induced liver necrosis and intravascular coagulation in rats enhanced by portacaval collateral circulation. Gut. 1975; 16:429–436.

10. Parratt JR, Sturgess RM. Evidence that prostaglandin release mediates pulmonary vasoconstriction induced by E. coli endotoxin. J Physiol. 1975; 246:79P–80P.

11. Starzl TE, Watanabe K, Porter KA, Putnam CW. Effects of insulin, glucagon, and insuling/glucagon infusions on liver morphology and cell division after complete portacaval shunt in dogs. Lancet. 1976; 1:821–825.

12. Witters P1, Maleux G, George C, Delcroix M, Hoffman I, Gewillig M, Verslype C, Monbaliu D, Aerts R, Pirenne J, et al. Congenital veno-venous malformations of the liver: widely variable clinical presentations. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2008; 23:e390–e394.

PDF

PDF ePub

ePub Citation

Citation Print

Print

XML Download

XML Download