Abstract

Endoscopic variceal ligation (EVL) can be performed as an optional therapy for gastric variceal bleeding if endoscopic sclerotherapy (ES) is not readily available or if practitioners lack experience. EVL using an endoscopic pneumo-activated ligating device was performed on a 53-year-old male patient with liver cirrhosis who presented with hematemesis. Follow-up esophagogastroduodenoscopy (EGD) performed two days after the EVL showed gastric perforation at the EVL-procedure site on the gastric fundus. However, the patient refused emergency surgery, and therefore received only supportive management, including intravenous antibiotics. EGD 10 days later showed healing of the perforation site. This is the first report of a case of gastric variceal bleeding with development of a gastric perforation soon after EVL, which showed complete recovery with conservative therapy and without surgical intervention.

Treatment of variceal bleeding has improved; however, variceal bleeding is still the most fatal complication of liver cirrhosis (1-3). Gastric varices occur in 5%-33% of patients with portal hypertension, and the incidence of bleeding is 25% in two years (4). Although gastric variceal bleeding occurs less frequently than esophageal variceal bleeding, it tends to be more severe, requiring greater amount of blood transfusion, with a higher rate of rebleeding and mortality, compared with esophageal variceal bleeding (4, 5).

There are several treatment options for gastric variceal bleeding, including endoscopic hemostasis, transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunt (TIPS), and balloon-occluded retrograde transvenous obliteration (BRTO) (6).

Endoscopic hemostasis has been used frequently in the treatment of patients with varices suffering from serious bleeding. In particular, due to the simplicity of the procedure, ES and EVL have been used frequently in patients with gastric variceal bleeding.

In general, complications are unusual in EVL for gastric varix, and gastric perforation occurs rarely after EVL (7, 8). We report here a case of gastric variceal bleeding with development of a gastric perforation soon after EVL, who recovered completely with conservative therapy, without surgical intervention.

A 53-year-old male patient with a 20-year history of alcohol use (50 g/day) and confirmed liver cirrhosis, was admitted to this medical center for hematemesis on November 23, 2002. His vital signs on admission were heart rate of 120 beats per minute, blood pressure of 90/60 mmHg, respiratory rate of 18 per minute, body temperature of 36.4℃, and room air oxygen saturation of 100%. On physical examination, the patient appeared to be acutely ill; anemic conjunctiva, spider angioma on the anterior chest, abdominal distension, and shifting dullness were also observed. Laboratory data showed hemoglobin level of 7.4 g/dL, white blood cell count of 11,400/µL, platelet count of 67,000/µL, serum creatinine of 1.2 mg/dL, blood urea nitrogen of 35 mg/dL, serum total bilirubin of 1.9 mg/dL, alkaline phosphatase of 231 IU/L, aspartate aminotransferase of 285 IU/L, alanine aminotransferase of 95 IU/L, albumin of 2.1 g/dL, and prothrombin time of 14.8 sec (International Normalized Ratio 1.26). Serum hepatitis B surface antigen and serum hepatitis C antibodies were negative. His Child-Pugh score was 8 (class B).

We started somatostatin (6 g/day) and cefotaxime (3 g/day) infusion but not gastric acid-suppressive agents. Two units of packed red blood cells were transfused and urgent esophagogastroduodenoscopy (EGD; GIF-XQ240, Olympus Optical Co., Tokyo, Japan) was performed. EGD findings showed a small non-bleeding esophageal varix and a nodular shaped gastric varix with stigmata at the fundus of the stomach. EVL was performed for emergency hemostasis using endoscopic pneumoactivated ligating devices (Sumitomo Bakelite Co., Ltd, Tokyo, Japan) in the left lateral decubitus position (Fig. 1). A sufficient amount of the lesion was sucked into the ligator cap, and a rubber band was applied to fully ligate the lesion. The procedure was completed without any events at that time.

However, two days after the EVL, the patient complained of abdominal pain, and a perforation was observed at the post-EVL ulcer base on the gastric fundus at follow-up EGD (Fig. 2A). Also, a few air bubbles were observed outside the posterior gastric wall of the fundus on abdominal computed tomography (Fig. 2B). We diagnosed perforation after the band ligation of the gastric varices and recommended emergency surgery. However, the patient refused to undergo an emergency operation and was therefore treated with a supportive therapy consisting of nothing-by-mouth status, intensive care unit management, and continued intravenous administration of antibiotics for 10 days. After 10 days, findings on EGD revealed healing of the perforation site (Fig. 3A). Oral intake was then resumed and the patient was discharged 25 days later. Three months after the discharge, a follow-up EGD indicated that the perforation site had healed completely (Fig. 3B).

Techniques such as BRTO and TIPS are costly procedures and are too invasive for general use. The main limitation of BRTO and TIPS for use in an emergency setting is that they require temporary control of bleeding with or without endoscopic therapy (9). Therefore, endoscopic hemostasis, such as ES and EVL, is recommended as the initial therapy (4, 10).

The effects of treatment with ES and EVL on variceal bleeding had been largely known to be similar (11). However, ES with cyanoacrylate has been reported to have a lower rebleeding rate than EVL (11) and has been recommended as an initial therapy (4). ES with tissue adhesives, however, requires experienced, skillful hands of practitioners. If tissue adhesives are not readily available or if practitioners lack experience, EVL can be performed as an optional therapy for treatment of gastric variceal bleeding (4).

There are few reports of gastric perforation after EVL of gastric varices; in fact, only three cases have been reported (7, 8). Surgical treatment was performed in all of these gastric perforation cases after EVL for gastric varices (7, 8), and recovery without surgical treatment has never been reported. Despite recent reports of successful endoscopic closure using a new device (12), surgical management is currently the standard treatment for a large perforation of the gastrointestinal tract (13). In our case, surgical treatment was considered the best option because our patient had a large perforation (about 3 mm in size). However, because the patient refused surgical treatment, only a supportive therapy was administered. Fortunately, the patient made a complete recovery without surgical intervention.

We suggest two possible explanations. One is that the perforation might have occurred due to transmural trapping of the gastric wall, and the other is that acidic condition due to gastric juice and enzymes in the stomach might have caused the perforation. In terms of the first reason, all layers of the stomach could be ligated with varices when suction and band ligation was performed using a cap fitted endoscope. Although the exact cause of the transmural ligation is not known, full thickness trapping of the gastric wall might account for the perforation (7). We hypothesize that the spatial relationship between the gastric wall and the fitted cap is not in an oblique orientation but in a vertical orientation in the fundus of the stomach, unlike the relationships of those in the esophagus. Therefore, all layers of the gastric wall, including the muscle and serosal layer, could be ligated. The resultant ischemia and necrosis of the ligated lesion might result in acute perforation. With regard to the second reason, spontaneous sloughing of the ligated lesion and an artificial ulcer could have been formed, and the healing process of the ulcer might have been interrupted by gastric juice and enzymes, leading to worsening of the ulcer and, eventually, a perforation. Somatostatin that we used for this case can delay ulcer healing as well as suppressing gastric acid (14, 15). In addition, the acid suppression effect of somatostatin is not as sufficient as proton pump inhibitor, the standard for ulcer treatment, which is another possible reason for the delayed healing process and perforation.

Gastric perforation after EVL is very rare; however, we should always keep in mind that gastric perforation may occur after EVL. This is a report on a patient with a visually identified large gastric perforation that developed soon after the endoscopic band ligation. The patient recovered completely with conservative therapy and without surgical intervention, and here we report this case.

In conclusion, EVL is a relatively safe and effective method for the treatment of variceal bleeding, but it may be associated with serious complications. It should be performed carefully in patients with fundal varices. The sucking force and volume should be carefully controlled so that necessary parts of the gastric wall are ligated, and strong acid suppressive therapy could be considered in order to prevent perforation due to iatrogenic ulcer.

Figures and Tables

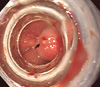

Fig. 1

Endoscopic view showing the ligated gastric varix. This finding indicates successful ligation of the gastric varix at its bleeding site.

References

1. Kim YS, Um SH, Ryu HS, Lee JB, Lee JW, Park DK, Kim YS, Jin YT, Chun HJ, Lee HS, et al. The prognosis of liver cirrhosis in recent years in Korea. J Korean Med Sci. 2003. 18:833–841.

2. De Franchis R, Primignani M. Natural history of portal hypertension in patients with cirrhosis. Clin Liver Dis. 2001. 5:645–663.

3. Seo YS, Kim YH, Ahn SH, Yu SK, Baik SK, Choi SK, Heo J, Hahn T, Yoo TW, Cho SH, et al. Clinical features and treatment outcomes of upper gastrointestinal bleeding in patients with cirrhosis. J Korean Med Sci. 2008. 23:635–643.

4. Garcia-Tsao G, Sanyal AJ, Grace ND, Carey W. Practice Guidelines Committee of the American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases. Practice Parameters Committee of the American College of Gastroenterology. Prevention and management of gastroesophageal varices and variceal hemorrhage in cirrhosis. Hepatology. 2007. 46:922–938.

5. Sarin SK, Lahoti D, Saxena SP, Murthy NS, Makwana UK. Prevalence, classification and natural history of gastric varices: a long-term follow-up study in 568 portal hypertension patients. Hepatology. 1992. 16:1343–1349.

6. Stiegmann GV, Goff JS, Michaletz-Onody PA, Korula J, Lieberman D, Saeed ZA, Reveille RM, Sun JH, Lowenstein SR. Endoscopic sclerotherapy as compared with endoscopic ligation for bleeding esophageal varices. N Engl J Med. 1992. 326:1527–1532.

7. Chen WC, Hou MC, Tsay SH, Lo SS, Lin HC, Chang FY, Lee SD. Gastric perforation after endoscopic ligation for gastric varices. Gastrointest Endosc. 2001. 54:99–101.

8. Takeuchi M, Nakai Y, Syu A, Okamoto E, Fujimoto J. Endoscopic ligation of gastric varices. Lancet. 1996. 348:1038.

9. Matsumoto A, Izumiya T, Takimoto K, Inokuchi H. Management of acute gastric variceal bleeding. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2003. 18:1173–1174.

10. Suk KT, Baik SK, Yoon JH, Cheong JY, Paik YH, Lee CH, Kim YS, Lee JW, Kim DJ, Cho SW, et al. Revision and update on clinical practice guideline for liver cirrhosis. Korean J Hepatol. 2012. 18:1–21.

11. Tan PC, Hou MC, Lin HC, Liu TT, Lee FY, Chang FY, Lee SD. A randomized trial of endoscopic treatment of acute gastric variceal hemorrhage: N-butyl-2-cyanoacrylate injection versus band ligation. Hepatology. 2006. 43:690–697.

12. Leung Ki EL, Lau JY. New endoscopic hemostasis methods. Clin Endosc. 2012. 45:224–229.

13. Hashiba K, Carvalho AM, Diniz G Jr, Barbosa de Aridrade N, Guedes CA, Siqueira Filho L, Lima CA, Coehlo HE, de Oliveira RA. Experimental endoscopic repair of gastric perforations with an omental patch and clips. Gastrointest Endosc. 2001. 54:500–504.

14. Tsibouris P, Zintzaras E, Lappas C, Moussia M, Tsianos G, Galeas T, Potamianos S. High-dose pantoprazole continuous infusion is superior to somatostatin after endoscopic hemostasis in patients with peptic ulcer bleeding. Am J Gastroenterol. 2007. 102:1192–1199.

15. Schmassmann A, Reubi JC. Cholecystokinin-B/gastrin receptors enhance wound healing in the rat gastric mucosa. J Clin Invest. 2000. 106:1021–1029.

PDF

PDF ePub

ePub Citation

Citation Print

Print

XML Download

XML Download