Abstract

Periodontal disease is a potential predictor of stroke and cognitive impairment. However, this association is unclear in adults aged 50 yr and above without a history of stroke or dementia. We evaluated the association between the number of teeth lost, indicating periodontal disease, and cognitive impairment in community-dwelling adults without any history of dementia or stroke. Dental examinations were performed on 438 adults older than 50 yr (315 females, mean age 63±7.8 yr; 123 males, mean age 61.5±8.5 yr) between January 2009 and December 2010. In the unadjusted analysis, odds ratios (OR) of cognitive impairment based on MMSE score were 2.46 (95% CI, 1.38-4.39) and 2.7 (95% CI, 1.57-4.64) for subjects who had lost 6-10 teeth and those who had lost more than 10 teeth, respectively, when compared with subjects who had lost 0-5 teeth. After adjusting for age, education level, hypertension, diabetes, hyperlipidemia, and smoking, the relationship remained significant (OR, 2.0; 95% CI, 1.08-3.69, P=0.027 for those with 6-10 teeth lost; OR, 2.26; 95% CI, 1.27-4.02, P=0.006 for those with more than 10 teeth lost). The number of teeth lost is correlated with cognitive impairment among community-dwelling adults aged 50 and above without any medical history of stroke or dementia.

Cognitive impairment is one of the most common geriatric neurological symptoms, and involves memory loss, judgment impairment, and abnormal behavior. It decreases an individual's quality of life and increases their social and familial burden. The proportion of the population aged 65 yr and above continues to steadily increase and is now about 11.4% in Korea (1). As a result, the incidence of dementia has increased and so has the burden on society of caring for the affected person. Early detection and proper management of well-recognized vascular risk factors such as hypertension, diabetes, smoking and hyperlipidemia are very important to prevent cognitive impairment.

Recently, a number of studies have reported that dental health status may be related to cognitive function (2-5, 7). Poor dental health is associated with both chronic inflammation and nutritional deficiency. It is one of the causes of cognitive impairment in older adults with or without dementia. To date, there have been very few studies conducted on community-dwelling adults aged 50 and over regarding the correlation between dental health status and cognitive function in Korea. In this study, we evaluated the relationship between cognitive impairment and tooth loss in community-dwelling adults aged 50 yr and above. We also aimed to provide basic data regarding the risk factors for cognitive impairment, which may aid in its early detection.

This study was conducted using registration lists of the PRESENT (Prevention of Stroke and Dementia) project. Established July 1, 2007, the PRESENT project is a regional government-funded project for the prevention of stroke and dementia though public education, public relations, early medical check-ups and research in Ansan City, Gyeonggi-do, Korea.

Participants recruited in the early medical check-up program between January 2009 and December 2010 included 650 individuals who were stroke- and dementia-free, apparently healthy, community-dwelling adults aged 50 yr and above. We excluded patients who had any history of cerebrovascular events or dementia; those with suspected dementia (DSM-IV), depression, or hypothyroidism; and those who had difficulty performing their daily activities or communicating with the researcher. Three hundred participants were recruited by systemic random sampling with administrational support from the regional government in 2009, and 350 participants were selected from volunteers who were identified as low economic status, defined as having an income below 200% of the minimum cost of living during 2010 (Fig. 1).

All participants received neurological examinations and in-person evaluations by a neurologist and trained research nurses. The in-person evaluation included medical questionnaires with questions regarding history of smoking, alcohol consumption, hypertension, diabetes, hyperlipidemia, stroke, and dementia. Questions concerning the education levels of participants were also included. 438 subjects also received comprehensive oral examinations, during which the location and the number of teeth that the participants had remaining were recorded. Cognitive functions were measured in all participants using the mini-mental status examination (MMSE), a widely used screening test (6), administered by psychologists and trained research nurses. Cognitive impairment was defined as an MMSE score of less than 24 (8, 9).

All results are presented as mean ± standard deviation. Statistical analyses were performed using SPSS® Ver.12.0 for Windows. Clinical variables were analyzed using independent t-tests and the chi-square test. The Pearson correlation and partial correlations analyses were conducted to analyze correlations between cognitive impairment, dental health status, and risk factors. Logistic regression analysis was conducted to determine independent factors that correlate with cognitive impairment after adjustment for gender, age, hypertension, diabetes, current smoking status, and hyperlipidemia. Differences were considered statistically significant at P < 0.05.

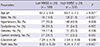

From the initial 650 participants without dementia or stroke at baseline, 438 adults aged 50 yr and above (315 women and 123 men) completed all evaluation processes. We divided the subjects into two groups based on their MMSE scores. The demographic characteristics of subjects are shown in Table 1. The mean age was 64.1 ± 7.84 yr and the mean MMSE score was 26.37 ± 3.68. Subjects in the lower MMSE group (< 24 score) were older and had lost more teeth than subjects in the higher MMSE group (≥ 24 score). Women were more likely to have a lower MMSE score. The number of teeth lost were significantly associated with older age (r = -0.238, P < 0.001), and lower MMSE scores (r = -0.459, P = 0.002) after adjustment for age and education level. However, there was no statistically significant association between the number of teeth lost and gender, albumin/protein ratio or body mass index (BMI).

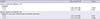

In the unadjusted analysis, odds ratio (OR) of cognitive impairment based on MMSE score were 2.46 (95% CI, 1.38-4.39) and 2.7 (95% CI, 1.57-4.64) for subjects who had lost 6-10 teeth and those who had lost more than 10 teeth, respectively, when compared with subjects who had lost 0-5 teeth. After adjustments for age, education level, hypertension, diabetes, hyperlipidemia, and smoking, the relationship remained statistically significant, as shown in Table 2 (OR, 1.99; 95% CI, 1.08-3.69, P = 0.027 for those with 6-10 teeth loss; OR, 2.26; 95% CI, 1.27-4.02, P = 0.006 for those with more than 10 teeth loss).

Dementia and cognitive impairment are growing health problems worldwide, and at present, there are no definite treatments for dementia. Therefore, it is important to identify modifiable risk factors to aid in the prevention of dementia. However, little is known about controllable risk factors, especially among the community-dwelling adults aged 50 yr and above. In this study, we found a significant association between cognitive impairment and tooth loss in adults aged 50 yr and above with no previous history of dementia or stroke. In addition, we found that tooth loss is independently correlated with cognitive impairment, after adjusting for confounding factors.

Tooth loss reflects a long term history of periodontal disease (5). Poor dental health status (i.e., tooth loss and periodontitis) is a common source of chronic infection in humans. Chronic inflammation, as measured by serum interleukin 6 and C-reactive protein levels, is reportedly a risk factor for cardiovascular disease, cognitive impairment, and Alzheimer's disease (AD) (2, 5, 7, 10, 11). Oral microbes or lipopolysaccharides of gram-negative bacteria are associated with elevated levels of inflammatory markers and contribute to the inflammatory burden of AD (5, 11-14). According to many studies, although inflammation is not an initiator of AD, inflammatory processes play a pivotal role in modulating the neuropathology of AD (5, 10, 11, 15, 16). Loss of functioning teeth is also associated with dietary changes. Nutritional status and tooth loss together cause nutritional deficiency, and a growing number of studies have suggested that cognitive impairment and nutrition are interrelated (2, 17-20). Furthermore, cognitive impairment may have adverse effects on dental health status. Patients with clinical dementia have been found to suffer from worse or more rapidly deteriorating dental health than their healthy peers (2). However, no correlation was found between albumin/protein ratio and tooth loss in this study, in contrast to the results of previous studies (2, 17). This will require the further research through prospective cohort study.

Previous studies have found that dental health status is related to dementia or the progression of cognitive impairment in elderly adults and dementia patients (2-5). The findings of our study are consistent with these studies (4, 5, 9), with our findings also extending to younger elderly adults aged 50 yr and above who do not suffer from dementia or stroke. Our study also demonstrates that the association between dental health status and cognitive function becomes more strongly correlated with increase in the number of teeth lost.

Even though these findings are notable, our study has some limitations. Firstly, because of mixed study samples, recruitment of subjects by systemic random sampling, and inclusion of volunteers who are more likely to be of generally low socioeconomic status, the study population may have not been representative of the general population. Secondly, we assessed cognitive functions using the MMSE only. The use of only the MMSE as an assessment tool is likely to produce inaccurate results for participants with low levels of education. Moreover, it is unlikely to detect dementia when the cut-off score for detection is between 24 and 26. Nevertheless, it is the most extensively used and characterized means for examining cognitive function. In this study, we also assessed these limitations after adjustment for confounding factors including age, gender or education level. In addition, it is uncertain whether cognitive impairment has been caused by tooth loss or whether cognitivie impairment brought about a difference in lifestyle habits that led to tooth loss because these findings are results from cross-sectional analysis based on baseline data.

In conclusion, we found that number of teeth lost is related to cognitive impairment. Furthermore, it might be possible to use it as a prediction factor in community-dwelling adults aged 50 yr and above with no history of dementia or stroke. Our results imply that an active education campaign for dental health should be considered as one of the potential methods for preventing cognitive impairment.

Notes

References

1. Korean Statistical Information Service. Statistics Korea;accessed on 5 January 2010. Available at http://www.kosis.kr.

2. Stewart R, Hirani V. Dental health and cognitive impairment in an English national survey population. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2007; 55:1410–1414.

3. Takata Y, Ansai T, Soh I, Sonoki K, Awano S, Hamasaki T, Yoshida A, Ohsumi T, Toyoshima K, Nishihara T, et al. Cognitive function and number of teeth in a community-dwelling elderly population without dementia. J Oral Rehabil. 2009; 36:808–813.

4. Kaye EK, Valencia A, Baba N, Spiro A 3rd, Dietrich T, Garcia RI. Tooth loss and periodontal disease predict poor cognitive function in older men. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2010; 58:713–718.

5. Wu B, Plassman BL, Liang J, Wei L. Cognitive function and dental care utilization among community-dwelling older adults. Am J Public Health. 2007; 97:2216–2221.

6. Folstein MF, Folstein SE, McHugh PR. "Mini-mental state". a practical method for grading the cognitive state of patients for the clinician. J Psychiatr Res. 1975; 12:189–198.

7. Minn YK, Suk SH, Park HY, Cheong JS, Yang HD, Lee SI, Do SY, Kang JS. Tooth loss is associated with brain white matter change and silent infarction among adults without dementia and stroke. J Korean Med Sci. 2013; 28:929–933.

8. Kang YW, Na DL, Hahn SH. A validity study on the Korean mini-mental state examination (K-MMSE) in dementia patients. J Korean Neurol Assoc. 1997; 15:300–308.

9. Kim JM, Shin IS, Yoon JS, Kim JH, Lee HY. Cut-off score on MMSE-K for screening of dementia in community dwelling old people. J Korean Geriatr Psychiatry. 2001; 5:163–168.

10. Grabe HJ, Schwahn C, Völzke H, Spitzer C, Freyberger HJ, John U, Mundt T, Biffar R, Kocher T. Tooth loss and cognitive impairment. J Clin Periodontol. 2009; 36:550–557.

11. Kamer AR, Craig RG, Dasanayake AP, Brys M, Glodzik-Sobanska L, de Leon MJ. Inflammation and Alzheimer's disease: possible role of periodontal diseases. Alzheimers Dement. 2008; 4:242–250.

12. Li X, Kolltveit KM, Tronstad L, Olsen I. Systemic diseases caused by oral infection. Clin Microbiol Rev. 2000; 13:547–558.

13. D'Aiuto F, Ready D, Tonetti MS. Periodontal disease and C-reactive protein-associated cardiovascular risk. J Periodontal Res. 2004; 39:236–241.

14. Taylor BA, Tofler GH, Carey HM, Morel-Kopp MC, Philcox S, Carter TR, Elliott MJ, Kull AD, Ward C, Schenck K. Full-mouth tooth extraction lowers systemic inflammatory and thrombotic markers of cardiovascular risk. J Dent Res. 2006; 85:74–78.

15. McGeer PL, McGeer EG. The inflammatory response system of brain: implications for therapy of Alzheimer and other neurodegenerative diseases. Brain Res Brain Res Rev. 1995; 21:195–218.

16. Finch CE, Crimmins EM. Inflammatory exposure and historical changes in human life-spans. Science. 2004; 305:1736–1739.

17. Kim JM, Stewart R, Prince M, Kim SW, Yang SJ, Shin IS, Yoon JS. Dental health, nutritional status and recent-onset dementia in a Korean community population. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2007; 22:850–855.

18. Bergdahl M, Habib R, Bergdahl J, Nyberg L, Nilsson LG. Natural teeth and cognitive function in humans. Scand J Psychol. 2007; 48:557–565.

19. Engelhart MJ, Geerlings MI, Ruitenberg A, van Swieten JC, Hofman A, Witteman JC, Breteler MM. Dietary intake of antioxidants and risk of Alzheimer disease. JAMA. 2002; 287:3223–3229.

20. Morris MC, Evans DA, Bienias JL, Tangney CC, Bennett DA, Aggarwal N, Wilson RS, Scherr PA. Dietary intake of antioxidant nutrients and the risk of incident Alzheimer disease in a biracial community study. JAMA. 2002; 287:3230–3237.

PDF

PDF ePub

ePub Citation

Citation Print

Print

XML Download

XML Download