Abstract

We report the case of 60-yr-old female in which therapeutic hypothermia (TH) was successfully induced maintaining the target temperature of 34℃ for 12 hr despite a risk of hypothermia-induced coagulation abnormalities following an emergent coronary artery bypass grafting (CABG) due to failed percutaneous coronary intervention, who suffered a cardiac arrest. Emergent CABG may be a relative contraindication for TH in post-cardiac arrest patients because hypothermia may increase the risk of infection and bleeding. However, the possibility of an improved neurologic outcome outweighs the risk of bleeding, although major surgery may be a relative contraindication for TH.

For post-cardiac arrest care, early coronary reperfusion is best achieved with primary percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI) and should be initiated as indicated in non-cardiac arrest patients, such as those with ST elevation myocardial infarction (STEMI) (1, 2). Primary PCI can be safely combined with therapeutic hypothermia and is associated with good neurological outcome in post-cardiac arrest patients (1, 3). Emergent coronary artery bypass grafting (CABG) after failed PCI is required in less than 1% of cases in institutes with a high case volume (4). Emergent CABG may be a relative contraindication for therapeutic hypothermia (TH) in post-cardiac arrest patients because hypothermia may increase the risk of infection and bleeding (5). However, recent studies have shown the successful application of TH in post-cardiac arrest patients with recent major surgery (6, 7) and pregnancy (8, 9), although they are relative contraindications. We report a successful experience with TH following an emergent CABG after failed primary PCI in a woman resuscitated following out-of-hospital cardiac arrest.

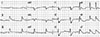

A 60-yr-old female without a significant past medical history presented to the emergency department (ED) with cardiac arrest on March 14, 2012. A security guard found her at her apartment and called for the emergency medical services (EMS). EMS personnel transported her to the ED without patient monitoring or basic life support for 10 min. She had collapsed 25 min before ED arrival and was in asystole. Return of spontaneous circulation (ROSC) was achieved after 14 min of advanced life support, including the application of 3 shocks, orotracheal intubation, and the administration of 4 mg adrenaline and 300 mg amiodarone. Her initial blood pressure was 68/49 mmHg, her pulse was 90 beats per minute, and her tympanic temperature was 36℃. The patient was comatose (Glasgow coma scale score E1VTM2=4) with a pupillary light reflex and self-respiration. The initial electrocardiogram showed atrial fibrillation with ST-segment elevation in leads V5-6, II, III, and aVF, indicating STEMI (Fig. 1). A blood gas analysis was significant for severe acidosis (pH 6.97; lactate 6.1 mM/L; BE -10.8). A 2D-echocardiogram performed by a cardiologist in the ED revealed moderate left ventricle systolic dysfunction, an ejection fraction of 30%-40% and akinesis of the basal-apical inferolateral wall and lateral wall. At 55 min after ROSC, she underwent PCI, which failed because the guide wire could not pass the lesion of completely occluded left proximal circumflex artery (LCx) due to extreme angulation. She also had 70% diffuse stenosis of the proximal and middle left anterior descending coronary artery on coronary angiogram. An intra-aortic balloon pump was applied because of her unstable vital signs, and she was transferred to the operating room for an emergent CABG at approximately 4 hr after ROSC. A hard segment in the proximal area of the LCx was observed in the heart, and the aortocoronary saphenous vein graft (SVG) was anastomosed to the second obtuse marginal branch of the LCx. The CABG was finished in 6 hr 20 min. She was brought to the intensive care unit (ICU) at 10 hr 25 min after ROSC. On arrival in the ICU her rectal temperature was 34.6℃. For cerebral protection, TH was initiated using an endovascular cooling system (Alsius Corp., Irvine, CA) with sedative and neuromuscular blocker infusion despite the risk of hypothermia-induced coagulation abnormalities after CABG. At 2 hr after TH initiation, her body temperature reached the target rectal temperature of 34℃, which was maintained for 12 hr. The patient was actively rewarmed to 36.5℃ at a rate of 0.25℃/hr (Fig. 2). During the maintenance of TH, her 12-hr postoperative blood loss was approximately 1,060 mL, and blood products, including 4 U of fresh-frozen plasma, 1 U of packed red blood cells and 1 U of single-donor platelets, were required to stabilise the patient. During TH, several coagulation parameters were altered, including prothrombin time (PT, 15.3-50.6 sec; reference range, 10-14 sec), international normalised ratio (INR, 1.36-4.23; reference range, 0.85-1.5), and activated partial thromboplastin time (aPPT, 46.2->120 sec; reference range, 23-35 sec). No complications were associated with hypothermia, except for coagulation abnormalities. On day 2, amplitude-integrated electroencephalography showed continuous normal voltage, and somatosensory-evoked potential showed bilateral N20 peaks. The patient regained consciousness at 36 hr after ROSC and was successfully extubated on day 5. Her mental state continued to show improvement to baseline despite a minor calculation disorder. She suffered pneumonia and pancreatitis during her stay in the ward and was discharged home with a cerebral performance category scale (CPC) score of 1 six weeks later.

To the best of our knowledge, this report is the first to describe a post-cardiac arrest patient in whom TH was successfully induced following an emergent CABG due to a failed PCI, although TH has been widely used during or after PCI for revascularisation in cardiac arrest.

Concurrent PCI and hypothermia are safe, with good outcomes reported for comatose cardiac arrest patients who undergo PCI (1). Emergency CABG after failed PCI is required in <1% of cases, and the subjects most likely to require it are those with evolving STEMI, cardiogenic shock, 3-vessel coronary artery disease, or the presence of a type C coronary arterial lesion (defined as >2 cm in length, an excessively tortuous proximal segment, an extremely angulated segment, a total occlusion >3 months in duration, or a degenerated SVG that appears to be friable) (10). However, when PCI fails, the safety of hypothermia after emergent CABG has not been demonstrated in post-cardiac arrest patients. CABG may be a relative contraindication for TH because hypothermia may increase the risk of infection and bleeding (5).

A few cardiac anaesthesiologists have recently reported terminating cardiopulmonary bypass (CPB) at a slightly hypothermic temperature to decrease neurological complications (11, 12). In a study by Nathan et al. (13), patients were initially cooled to 32℃ and then randomly assigned to 37℃ (control) or 34℃ (hypothermia). There was no further intraoperative warming during CPB, and patients arrived in the ICU with temperatures of 33.6±0.5℃ in the hypothermic group and 35.3±0.6℃ in the control group. An extended period of mild hypothermia (<5 hr) reduced the incidence and severity of cognitive deficits. The 12-hr ICU blood losses of the 2 groups did not differ significantly (control, 812±493 mL; hypothermia, 858±592 mL; mean±SD). This finding is similar to the 12-hr ICU blood loss observed while maintaining TH in our patient (1,060 mL), although coagulation abnormalities were observed and treated.

In contrast, Insler et al. (14) reported that patients who arrive in the ICU after coronary artery surgery with a temperature <36℃ are at a significantly increased risk of death, excessive bleeding, and other complications compared with normothermic patients. Commonly, temperatures of 34℃ to 35℃ are acceptable in cardiac surgery patients, while temperatures below those could potentiate an environment conducive of arrhythmogenicity. The use of TH can be encouraged after ROSC in cardiac surgery settings because more advantageous treatment options are not available (15). Temperatures of 33℃ to 35℃ affect platelet function only, and other coagulation factors are affected only when temperatures decrease below 33℃ (16). In our case, TH was maintained at a target of 34℃, but coagulation parameters, such as PT, aPTT, and INR, were prolonged, indicating coagulation abnormalities. However, these abnormalities might be influenced by a high dose of heparin and CPB pump application (17).

In a case study (7), intraoperative thrombolysis was successfully used in a cardiac arrest patient undergoing caesarean delivery due to pulmonary embolism, although massive bleeding from the uterus was anticipated. In addition, mild hypothermia (32℃ to 34℃) was induced for 12 hr with no further major bleeding from the uterus, and the patient regained consciousness on day 3. Therefore, we believe that the possibility of an improved neurologic outcome outweighs the risk of bleeding, although major surgery may be a relative contraindication for TH.

In conclusion, this case suggests that TH (34℃ for 12 hr) following an emergent CABG after failed primary PCI can be safely used in a comatose cardiac arrest patient.

Figures and Tables

References

1. Peberdy MA, Callaway CW, Neumar RW, Geocadin RG, Zimmerman JL, Donnino M, Gabrielli A, Silvers SM, Zaritsky AL, Merchant R, et al. Part 9: post-cardiac arrest care: 2010 American Heart Association Guidelines for Cardiopulmonary Resuscitation and Emergency Cardiovascular Care. Circulation. 2010; 122:S768–S786.

2. Nolan JP, Soar J. Post resuscitation care: time for a care bundle? Resuscitation. 2008; 76:161–162.

3. Gräsner JT, Meybohm P, Caliebe A, Böttiger BW, Wnent J, Messelken M, Jantzen T, Zeng T, Strickmann B, Bohn A, et al. Postresuscitation care with mild therapeutic hypothermia and coronary intervention after out-of-hospital cardiopulmonary resuscitation: a prospective registry analysis. Crit Care. 2011; 15:R61.

4. Roy P, de Labriolle A, Hanna N, Bonello L, Okabe T, Pinto Slottow TL, Steinberg DH, Torguson R, Kaneshige K, Xue Z, et al. Requirement for emergent coronary artery bypass surgery following percutaneous coronary intervention in the stent era. Am J Cardiol. 2009; 103:950–953.

5. Greer DM. Hypothermia for cardiac arrest. Curr Neurol Neurosci Rep. 2006; 6:518–524.

6. Smith C, Coleman A, Al-Baghdadi Y, Orlewicz M. Therapeutic hypothermia in PEA cardiac arrest for global and local cerebral protection: a case report and mini-review. J Rom Anest Terap Int. 2011; 18:153–155.

7. Wenk M, Pöpping DM, Hillyard S, Albers H, Möllmann M. Intraoperative thrombolysis in a patient with cardiopulmonary arrest undergoing caesarean delivery. Anaesth Intensive Care. 2011; 39:671–674.

8. Wible EF, Kass JS, Lopez GA. A report of fetal demise during therapeutic hypothermia after cardiac arrest. Neurocrit Care. 2010; 13:239–242.

9. Rittenberger JC, Kelly E, Jang D, Greer K, Heffner A. Successful outcome utilizing hypothermia after cardiac arrest in pregnancy: a case report. Crit Care Med. 2008; 36:1354–1356.

10. Hillis LD, Smith PK, Anderson JL, Bittl JA, Bridges CR, Byrne JG, Cigarroa JE, DiSesa VJ, Hiratzka LF, Hutter AM Jr, et al. 2011 ACCF/AHA guideline for coronary artery bypass graft surgery: executive summary: a report of the American College of Cardiology Foundation/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2012; 143:4–34.

11. Nathan HJ, Rodriguez R, Wozny D, Dupuis JY, Rubens FD, Bryson GL, Wells G. Neuroprotective effect of mild hypothermia in patients undergoing coronary artery surgery with cardiopulmonary bypass: five-year follow-up of a randomized trial. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2007; 133:1206–1211.

12. Sahu B, Chauhan S, Kiran U, Bisoi A, Lakshmy R, Selvaraj T, Nehra A. Neurocognitive function in patients undergoing coronary artery bypass graft surgery with cardiopulmonary bypass: the effect of two different rewarming strategies. J Cardiothorac Vasc Anesth. 2009; 23:14–21.

13. Nathan HJ, Wells GA, Munson JL, Wozny D. Neuroprotective effect of mild hypothermia in patients undergoing coronary artery surgery with cardiopulmonary bypass: a randomized trial. Circulation. 2001; 104:I85–I91.

14. Insler SR, O'Connor MS, Leventhal MJ, Nelson DR, Starr NJ. Association between postoperative hypothermia and adverse outcome after coronary artery bypass surgery. Ann Thorac Surg. 2000; 70:175–181.

15. Chakravarthy M. Therapeutic hypothermia after cardiac arrest during surgery: a meaningful pursuit? Ann Card Anaesth. 2009; 12:101–103.

16. Polderman KH. Mechanisms of action, physiological effects, and complications of hypothermia. Crit Care Med. 2009; 37:S186–S202.

17. Eaton MP, Iannoli EM. Coagulation considerations for infants and children undergoing cardiopulmonary bypass. Paediatr Anaesth. 2011; 21:31–42.

PDF

PDF ePub

ePub Citation

Citation Print

Print

XML Download

XML Download