INTRODUCTION

Influenza A virus infection may present various clinical manifestation. Although it usually shows as upper and lower respiratory tract infection, uncommonly, skin lesions such as maculopapular eruption or vasculitic lesion can be observed. The mechanisms by which an infectious agent triggers a vasculitic process are various, and major mechanisms are 1) direct pathogen invasion and damage of the endothelial cells and 2) immune-mediated damage to the vessel walls and 3) stimulation of lymphocyte proliferation (1). In medical literatures, only two cases of vasculitis associated with influenza infection have been reported (2, 3), but these cases were just diagnosed as vasculitis clinically without histopathological confirmation by skin biopsy. Here, we report a case of leukocytoclastic vasculitis (LCV) which was diagnosed by skin biopsy associated influenza A virus infection and treated with oseltamivir (Tamiflu®) and prednisolone.

CASE DESCRIPTION

A 2-yr-old Korean girl visited for purpuric skin lesions on June 24, 2011. She was previously healthy and weighed 12 kg. One week before, she had clear rhinorrhea without sore throat, cough or fever. Afterward, the lesions were firstly observed on the lower legs 4 days ago and had been rapidly extended to face and upper extremities with fever. She had none of any known disease and no history of drug medication or allergy.

At admission, she looked sick with a body temperature of 38.4℃ and did not complain of abdominal pain or arthralgia. On examination, she presented multiple rice grain to walnut sized palpable purpuric and hemorrhagic lesions on the face and extremities (Fig. 1) without heatness or tenderness on palpation. The lesions were variable sized, some lesions were reticulated.

Laboratory tests showed leukocytosis (white blood cells 19,230/µL: neutrophils 16,150/µL [84%]), elevated C-reactive protein (4.825 mg/dL), elevated D-dimer (12.016 µg/mL), and decreased partial thromboplastin time (21.9 sec). Liver function test and urine analysis were within normal limits. Specific laboratory studies for ruling out immunological and autoimmune disorder including anti-nuclear antibody (ANA), anti-double stranded DNA antibody, anti-neutrophilic cytoplasmic antibody (ANCA), anti-Ro antibody, anti-La antibody, anti-Scl antibody, anti-Smith antibody, rheumatoid factor, and cold agglutinin test were within normal limits or negative. Also, chest X-ray was normal and blood culture for bacteria revealed no growth. Then, skin biopsy was done on the right lower leg.

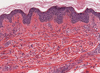

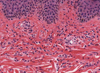

Histopathologic finding revealed perivascular inflammatory cell infiltrations in the dermis (Fig. 2). On the high-power view, perivascular neutrophilic infiltrations with nuclear dusts, extravasated red blood cells, and fibrin deposition of the small vessel wall were observed (Fig. 3). Immunofluorescence studies of specimen including IgG, IgA, IgM, and C3 were negative.

With these clinical, laboratory, and histopathologic findings, leukocytoclastic vasculitis due to bacterial infection was suspected and prednisolone (4 mg three times a day, orally) and cephalosporin (450 mg twice a day, intravenously) were administered. Despite the treatment for 3 days, new vasculitic lesions occurred, and the body temperature did not return to normal.

On hospital day 4, influenza A virus was isolated from nasopharyngeal swab by reverse-transcriptase polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR) assay which was performed at admission. Then, cephalosporin was stopped and oseltamivir (Tamiflu®, 30 mg twice a day, orally) was added immediately for 5 days. Although her body temperature returned to normal in 24 hr, new vasculitic lesions were persistently developed. Dose of prednisolone increased up to 24 mg and there was significant improvement of the vasculitic lesion after three days. On hospital day 12, all skin lesions were disappeared and she was discharged to home. No recurrence of vasculitic skin lesions was observed for 2 months of follow-up.

DISCUSSION

Leukocytoclastic vasculitis (LCV) is a histopathologic term commonly used to denote a small-vessel vasculitis characterized by a combination of vascular damage and an infiltrate composed largely of neutrophils histopathologically. Because fragmentation of nuclei is observed, the term LCV is frequently used. It may be a primary disorder or develop secondary to other conditions including connective tissue diseases, malignancies, drugs, and infections. In case of LCV caused by viral infections, hepatitis B virus, hepatitis C virus, human immunodeficiency virus, and parvovirus B 19 are common infectious agents (4). Two cases of vasculitis caused by influenza A virus infection had been reported in medical literatures (2, 3).

The classic manifestations of influenza A virus infection include sudden onset of fever, chill, cough, sore throat, rhinorrhea, headache, myalgia, and general weakness (5). Although most diseases are acute and self-limited, it can be severe in cases of age 2 or younger, age 65 or older, pregnancy, and chronic medical conditions (6), and presented with nonspecific manifestations consisted of nonspecific febrile illness, or other respiratory tract symptoms such as croup bronchiltis, bronchiolitis, and pneumonia (7). Also, gastrointestinal symptoms and skin lesions can be uncommonly observed (8, 9).

Cutaneous manifestation associated with influenza A virus infection usually presents maculopapular eruption. According to Hope-Simpson and Higgins' study (9), about 2% of influenza A virus infections are associated with rash, but the aspect of rash was not described in detail. In addition, although Ryan-Poirier (7) noted various skin lesions which were observed in a small percentage of children with influenza virus infection, specific cases which were suspected as vasculitic skin lesions were not presented.

In our case, although there was no definite proof that influenza A virus infection induced LCV, there was several clues: 1) After diagnosis of LCV by skin biopsy, influenza A virus was isolated from nasopharyngeal swab. 2) There was no effect with combination treatment of ceftriaxone and prednisolone, but was dramatic effect with combination treatment of oseltamivir and prednisolone. 3) The patient had none of any known underlying disease and no history of drug medication, vaccination or allergy to induce vasculitis. 4) There was no abnormality to cause vasculitis in laboratory tests.

To the best of our knowledge, few cases of influenza infection with skin lesion thought to be vasculitis have been reported. First, Silva et al. (2) reported a case of 3-yr-old boy with acute fever and petechial rash associated with influenza A virus infection in 1999. Also, Urso et al. (3) described a case of 23-yr-old Caucasian woman with acute fever, hemorrhagic skin lesions, and severe abdominal pain associated with pandemic 2009 (H1N1) infection diagnosed as Henoch-Schönlein purpura in 2011. In the both of previous mentioned articles, skin lesions were considered to be vasculitis by mentioned content or photography. However, there were no confirmation by skin biopsy in the both cases. Therefore, we firstly report a case of LCV associated influenza A virus infection diagnosed by skin biopsy and treated with oseltamivir (Tamiflu®) and prednisolone.

PDF

PDF ePub

ePub Citation

Citation Print

Print

XML Download

XML Download