Abstract

The disparity between patients awaiting transplantation and available organs forced many patients to go overseas to receive a transplant. Few data concerning overseas transplantation in Korea are available and the Korea Society for Transplantation conducted a survey to evaluate the trend and outcome of overseas transplantation. The survey, conducted on June 2006, included 25 hospitals nationwide that followed up patients after receiving kidney transplant (KT) or liver transplant (LT) overseas. The number of KT increased from 6 in 2001 to 206 in 2005 and for LT from 1 to 261. The information about overseas transplant came mostly from other patients (57%). The mean cost for KT was $21,000 and for LT $47,000. Patients were admitted for 18.5 days for KT and 43.4 days for LT. Graft and patient survival was 96.8% and 96.5% for KT (median follow up 23.1 months). Complication occurred in 42.5% including surgical complication (5.3%), acute rejection (9.7%) and infection (21.5%). Patient survival for LT was 91.8% (median follow up 21.2 months). Complication occurred in 44.7% including 19.4% biliary complication. Overseas KT and LT increased rapidly from 2001 to 2005. Survival of patients and grafts was comparable to domestic organ transplantation, but had a high complication rate.

The development of organ transplantation (OT) has prolonged and improved the lives of thousands of patients worldwide. However, these outstanding accomplishments have been tarnished by the numerous reports about organ trafficking using underprivileged human beings as sources of organs for more prosperous and wealthy patients. (1). At the Second Global Consultation on Human Transplantation of the World Health Organization (WHO) in March 2007, it was estimated that organ trafficking accounts for 5%-10% of the kidney transplants (KT) performed annually throughout the world (2). There have been various reports that OT is performed not only in underdeveloped or developing countries such as Pakistan, Iran, the Philippines, India, Mainland China, Eastern Europe, South America or South Africa, but also in developed countries such as Belgium, Germany, and Italy (3-7). Even in the United States, because the access to brain death donors is easier than most underdeveloped countries, wealthy patients from underdeveloped countries come to the US to receive OT (3, 5).

This is no exception in Korea. Overseas OT first began in 1999 where a patient went to Mainland China to receive a KT and 2001 for LT. However, there has been no data concerning the magnitude and trend of OT nationwide except for sporadic reports from single centers (8, 9). The Korean Society for Transplantation has therefore conducted a nationwide survey to evaluate the trend and outcome of overseas OT in Korea.

The survey was conducted in June 2006. A list of patient questionnaires was sent to all of the hospitals that had followed up patients after receiving OT overseas. It included 25 hospitals for KT and 13 hospitals for LT. The questionnaire included access to information of overseas OT center, expense (operation cost and total expense), duration of hospitalization, complications during follow up period, graft survival, patient survival, and cause of death. The questionnaires were filled in by the medical staff members.

The questionnaire included 462 patients that received KT and 504 patients that received LT. All the patients received OT from Mainland China. KT was performed in 28 centers and LT in 5 centers nationwide.

Most of the information about overseas OT center came from other patients (57%). Other 43% of the patients obtained information from a friend or known persons. About 4% of the patients got the information from the doctor and 3% from the internet, which was surprisingly low since according to the investigation done by the author in year 2006, there was about 1,700 users in 14 internet homepages concerning overseas OT in Korea. Another 8% of the patients were informed by Chinese brokers.

The mean operation fee to get a KT was US$21,000 (US$15,000-US$46,000), and another US$21,000 (US$15,000-US$32,000) was necessary for other expense during the stay. The mean hospital stay was 18.5 days ranging from 14 to 90 days.

For LT the needed expense was about twice of KT; the operation fee was US$47,000 (US$41,000-US$160,000), and extra expense of US$16,000 (US$8,600-US$25,000) was necessary during the stay. The mean hospital stay was 43.4 days (range 7-84 days) which was also twice longer than KT.

The number of OT overseas performed annually is shown in Figs. 1, 2. Until 2001, only 6 cases of KT was performed which increased each year reaching 206 cases in the year 2005. In 2001, overseas KT constituted only 1% of the total annual KT cases performed in Korea but by year 2005, it included 21.2%. In comparison to the rapid increase of overseas KT, the number of deceased donor KT has not increased much during 2001 and 2005 and by 2005, the fraction of KT operated overseas has surpassed the proportion of deceased donor KT (17.0% in 2001 and 17.8% in 2005). Total of 434 cases of overseas KT has been done by 2005 since the first KT in 1999 (Fig. 1). In comparison to KT, there was only one simultaneous pancreas-kidney transplantation performed annually from 2002 to 2004, and there was none in 2005.

The first case of overseas LT was done in 2001, with an exponential increase every year reaching 261 cases by the year 2005. In 2005, overseas LT constituted for 30.5% of total annual LT cases in Korea, and was almost four times the number of deceased donor LT. There has been a total of 490 cumulative LT cases until 2005 and the number has outrun the number of KT since 2004 (Fig. 2).

Due to the nature of data acquisition, detailed description of each patient was not available and the exact patient and graft survival was not possible to obtain. Nevertheless, with a median follow up of 23.1 months, death-censored graft survival was 96.8%, and patient survival was 96.5%. Fifteen patients died (mortality rate 3.5%). Infection was the most common cause of death (sepsis in 4, necrotizing fasciitis 1, aspergillosis 1), and intracranial hemorrhage occurred in 1 patients. The cause of death of remaining 8 patients was not described and could not be evaluated.

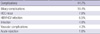

Complication rate was 42.5%. The most frequent complication was infection which accounted for 21.5%, followed by acute rejection 9.7% and surgical complication 5.3%. Cytomegalovirus infection developed in 4.8%, pneumonia in 4.6%, urinary tract infection in 3.9%, wound infection in 3.7%, herpes zoster in 2.1%, BK virus nephropathy in 2.1%, and pyelonephritis in 0.2%. The type of pneumonia was bacterial pneumonia 1.6%, tuberculosis 1.6%, and Pneumocystis carinii pneumonia 1.4%. Ureterovescical anastomosis leakage occurred in 2.1%, hydronephrosis in 1.2%, vascular complication in 0.9%, lymphocele in 0.7% and ureterovescical reflux in 0.5% (Table 1).

The most common cause of LT was hepatitis B related liver cirrhosis (62.8%), followed by hepatitis B related hepatocellular carcinoma (22.4%), hepatitis C related liver cirrhosis (4.7%), and retransplantation (2.1%). Other causes including alcoholic liver cirrhosis, autoimmune hepatitis consisted of 8.3%. Hepatitis B related liver disease was the etiology in 85.2% which is a relatively similar distribution to the LT done within Korea.

With a median follow up of 21.2 months, patient survival was 91.8%. This percentage does not represents overall patient survival of LT, but only of patients who could return to Korea to be followed up. Among the 40 patients that died (mortality rate 8.2%), the cause of death was describe in only 26; hepatocellular carcinoma recurrence 11, sepsis 9, hepatitis virus (either B or C) recurrence 3, and intracranial hemorrhage 3.

Complication developed in 44.7%. Biliary complication was the most common cause 19.4%, followed by hepatocellular carcinoma recurrence 7.8%, hepatitis B or C recurrence 6.5%, bacterial infection 4.9%, vascular complication 4.3%, and acute rejection 1.8%. Other complications such as wound infection, incisional hernia, graft versus host disease and bleeding consisted of 15.6% (Table 2).

OT prolongs life and improves life quality of patients with end stage organ failure and is regarded as the treatment option. However, due to the discrepancy between patients willing to get a transplant and the donors available, many patients die while waiting for an organ. According to the Korean Network for Organ Sharing (KONOS), the number of patients in the KT waiting list reached 7,641 by 2008, but only 481 patients (one out of 15) received a deceased donor KT. Patients in the LT waiting list was 2,596, but only 481 patients got deceased donor LT (10). In countries such as Korea, where brain death donation is not active, in order to meet the demands of organs, living donor OT is performed as an alternative. Living donor KT accounted for 59.8% and living donor LT 78.9% of all OT performed in 2008 (10). As a result, when a suitable living donor was not available, patients had to turn their eyes on getting an OT overseas.

Medical tourism for OT usually occurs in countries where donors are readily accessible. Although OT by means of organ trafficking are usually done in less developed countries, medical tourism is not an issue of 'underdeveloped' countries only. It is estimated that about 0.8% of KT recipients and 1.5% of LT recipients in the USA are of foreigners, which implies that many foreign patients enter to the USA to 'purchase' an organ (3, 5). Foreign patients can legally receive deceased donor OT in Korea, but due to the scarcity of available deceased donors, 'purchase' of deceased donor organ is rather unrealistic. According to the KONOS data (personal communication) all foreigners that underwent OT in Korea used living donors. Organ trafficking is strictly forbidden in Korea and all living donor OT must receive permission from KONOS, where thorough investigation of familial relationship is done, to carry out OT.

All the overseas OT in Korea from our data was done in Mainland China. The main ethical issue is that most of the organ donors in Mainland China come from executed prisoners. According to the Chinese Deputy Minister of Health, Huang Jiefu, approximately 95% of all organs used for transplantation are from executed prisoners and it is estimated that about 10% are used in organ trafficking (2, 11). On October 2007 the Chinese Medical Association agreed on a moratorium of commercial organ harvesting from condemned prisoners, and agreed to restrict transplantations from donors to their immediate relatives (12, 13). Since the survey was conducted between 2000 and 2005, the increase of overseas OT reflects the increase of organ trafficking within China. Further data of overseas OT will be necessary to evaluate the impact of the moratorium.

However, the issue of overseas OT does not lie solely on ethical issues but also medical. According to Kennedy and colleagues, 5 patient of 16 died during the course of overseas KT, and concluded that the patient and graft survival were worse than KT within Australia (4). Similar concern was raised concerning LT, where 1 and 5 yr survival rate was lower among overseas LT recipients (90% and 77% vs 93% and 93%) (14). On the other hand, others have reported that overseas OT had similar results (15-17). Our results show that patient and graft survival of both KT and LT recipients are comparable to that of domestic KT and LT recipients. Mortality rate for KT was 3.5% at 23.1 months median follow up and 8.2% for LT at 21.2 months. Nevertheless, it should be stressed that these results were based only on patients who return home excluding in hospital mortality and not of all the patients that went abroad. Shibolet and collegues reported that in spite of successful transportation overseas by precautious measures taken during long-distance transportation, a mortality rate of 30.2% occurred in patients while waiting for LT or following LT overseas (6). Therefore we cannot draw any conclusions on whether the overall patient and graft mortality of overseas OT was really 'comparable'.

Concern of higher complication rate is another issue. Alghamdi reported that overseas KT patients had a higher percentage of acute rejection compared to the patients transplanted within Saudi Arabia (27.9% vs 9.9%, P = 0.005) (17). Others have described a higher rate of fungal, CMV, HIV, or hepatitis B or C infection, or urological complication among overseas KT recipients (4, 9, 15-18). According to our data, KT recipients experienced a relatively high postoperative complication rate of 42.5%, with infection as the most common cause. However, surgical complication and acute rejection rate was relatively low (5.3% and 9.7%).

The complication rate of LT reached 44.7%, with 19.7% biliary complication as the most common etiology. Although not much is known about the quality and nature of the donor liver, whether it is a brain death or cardiac death donor, the complication rate of biliary complication is higher compared to orthotopic LT using brain death donors which is reported to be 5%-15% (19) and lower compared to cardiac death donors which is reported to be around 30% (20).

De novo infection of hepatitis B or C is also another major problem. It is essential to get sufficient information about the donor as well as the recipients before and after LT, and failure to do so may result in detrimental consequences for the recipient. A major drawback to resolving this issue is that most of the LT performed overseas are associated with organ trafficking mostly done 'undercover' (15).

The wide discrepancy between available donors and recipients on the waiting list has forced many patients to involuntarily choose overseas organ transplantation. This has not only posed ethical problems, since most of the donors are from executed prisoners, but also medical concerns due to lack of communication between centers and information about the donors and recipients. Efforts to better communicate patient information should be made to enhance the postoperative care of patients whom otherwise may not receive the proper medical care after returning home. Moreover, to resolve the current discouraging experience we must push forward to expanding the donor pool more aggressively. The exponential growth of overseas OT, along with the ethical and medical problems underlying the process, became an important social issue in Korea since 2003, and these events highlighted the importance of increasing the donor pool and helped soften the social and cultural attitude towards donation after death, which like in many other Asian countries, has been an important drawback in increasing the donor pool. Together with much effort of both the medical as well as social and legal community, the number of deceased donors has increased from 91 in 2005 to 261 in 2009, and a new law on OT has been passed on May 2010 to boost donor action program (10). It is therefore important to bring out these issues openly to help rebuild a better system and try to achieve self sufficiency as emphasized by WHO (21).

Figures and Tables

Fig. 1

Annual number of kidney transplantation reported in Korea. The proportion of domestic deceased donor, domestic living donor and overseas kidney transplantation is shown. The proportion of domestic deceased donor kidney transplantation has not changed over time (from 17.0% to 17.8%) while overseas transplantation has increased abruptly since 2002. Deceased (□), living (■), and overseas (■) kidney transplantation.

Fig. 2

Annual number of liver transplantation reported in Korea. Overseas domestic deceased donor, domestic living donor and overseas liver transplantation is shown. Overseas transplantation has increased exponentially since 2002. Deceased (□), living (■), and overseas (■) liver transplantation.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors thank all the doctors, nurses, coordinators from 25 hospitals who helped gather the data for analysis: (In alphabetical order) Ajou University Medical Center, Asan Medical Center of University of Ulsan, Chonbuk National University Hospital, Chonnam National University Hospital, Chungnam National University Hospital, Dong-A University Medical Center, Dongsan Medical Center of Keimyung University, Ewha Womans University Mokdong Hospital, Gyeongsang National University Hospital, Hanyang University Medical Center, Inha University Hospital, Inje University Busan-Paik Hospital, Inje University Paik Hospital, Kangdong Sacred Heart Hospital of Hallym University, Korea University Guro Hospital, Koshin University Gospel Hospital, Kyung Hee University Medical Center, Kyungpook National University Hospital, Myongji Hospital, Samsung Medical Center of Sungkyunkwan University, Seoul National University Hospital, Seoul St. Mary's Hospital of Catholic University of Korea, Soonchunhyang University Bucheon Hospital, Ulsan University Hospital, Yonsei University Severance Hospital.

AUTHOR SUMMARY

Trend and Outcome of Korean Patients Receiving Overseas Solid Organ Transplantation between 1999 and 2005

Choon Hyuck David Kwon, Suk-Koo Lee, and Jongwon Ha

The disparity between patients awaiting transplantation and available organs forced many patients to go overseas to receive solid organ transplantation but few data concerning overseas transplantation are available. The Korea Society for Transplantation conducted a survey on June 2006 to evaluate the trend and outcome of overseas transplantation which included 25 hospitals nationwide that followed up patients after receiving kidney transplant (KT) or liver transplant (LT) overseas. The number of KT increased from 6 to 206 and for LT from 1 to 261 between 2001 and 2005. Patient survival was 96.5% for KT at 23.2 months follow up and complication occurred in 42.5% including surgical complication (5.3%), acute rejection (9.7%) and infection (21.5%). Patient survival for LT was 91.8% (median follow up 21.2 months) with complication rate of 44.7% including 19.4% biliary complication. Overseas KT and LT increased rapidly from 2001 to 2005. Patient survival was comparable to domestic organ transplantation, but had a high complication rate.

References

1. International Summit on Transplant Tourism and Organ Trafficking. The declaration of Istanbul on organ trafficking and transplant tourism. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2008. 3:1227–1231.

2. Budiani-Saberi DA, Delmonico FL. Organ trafficking and transplant tourism: a commentary on the global realities. Am J Transplant. 2008. 8:925–929.

3. Freeman RB. "Transplant tourism" in the United States? Transplantation. 2007. 84:1559–1560.

4. Kennedy SE, Shen Y, Charlesworth JA, Mackie JD, Mahony JD, Kelly JJ, Pussell BA. Outcome of overseas commercial kidney transplantation: an Australian perspective. Med J Aust. 2005. 182:224–227.

5. Schold JD, Meier-Kriesche HU, Duncan RP, Reed AI. Deceased donor kidney and liver transplantation to nonresident aliens in the United States. Transplantation. 2007. 84:1548–1556.

6. Shibolet O, Rowe M, Safadi R, Levy I, Zamir G, Eid A, Donchin Y, Ilan Y, Shouval D. Air transportation of patients with end-stage liver disease to distant liver transplantation centers. Liver Transpl. 2005. 11:650–655.

7. Merion RM, Barnes AD, Lin M, Ashby VB, McBride V, Ortiz-Rios E, Welch JC, Levine GN, Port FK, Burdick J. Transplants in foreign countries among patients removed from the US transplant waiting list. Am J Transplant. 2008. 8:988–996.

8. Baek BS, Choi DL, Han YS, Kim MK. Clinical features of patients who received liver transplantation in China. J Korean Soc Transplant. 2006. 20:248–252.

9. Kang WN, Ju MK, Chang HK, Ahn HJ, Jeun KO, Kim HJ, Kim MS, Kim SI, Kim YS. Surgical Complications are major problems concerning overseas kidney transplantation in comparison study with domestic deceased donor kidney transplantation. J Korean Soc Transplant. 2007. 21:119–122.

10. 2008 Annual Data Report. Korean Network for Organ Sharing (KONOS). accessed on Aug 20 2009. Available at http://konos.go.kr.

11. Huang J. Ethical and legislative perspectives on liver transplantation in the People's Republic of China. Liver Transpl. 2007. 13:193–196.

12. Pact to block harvesting of inmate organs. South China Morning Post. 2007. 10. 07. 1.

13. Chinese Medical Association Reaches Agreement With World Medical Association Against Transplantation Of Prisioners's (sic) Organs. Medical News Today. 2007. 10. 07.

14. Sugo H, Balderson GA, Crawford DH, Fawcett J, Lynch SV, Strong RW, Futagawa S. Overseas liver transplantation for hepatitis C in Japanese patients: a comparison with patients from Australia/New Zealand. Transplant Proc. 2002. 34:3323–3324.

15. Canales MT, Kasiske BL, Rosenberg ME. Transplant tourism: Outcomes of United States residents who undergo kidney transplantation overseas. Transplantation. 2006. 82:1658–1661.

16. The Living Non-Related Renal Transplant Study Group. Commercially motivated renal transplantation: results in 540 patients transplanted in India. Clin Transplant. 1997. 11:536–544.

17. Alghamdi SA, Nabi ZG, Alkhafaji DM, Askandrani SA, Abdelsalam MS, Shukri MM, Eldali AM, Adra CN, Alkurbi LA, Albaqumi MN. Transplant tourism outcome: a single center experience. Transplantation. 2010. 90:184–188.

18. Ivanovski N, Masin J, Rambabova-Busljetic I, Pusevski V, Dohcev S, Ivanovski O, Popov Z. The outcome of commercial kidney transplant tourism in Pakistan. Clin Transplant. 2010. 07. 06. [Epub ahead of print].

19. Sharma S, Gurakar A, Jabbour N. Biliary strictures following liver transplantation: past, present and preventive strategies. Liver Transpl. 2008. 14:759–769.

20. Reich DJ, Hong JC. Current status of donation after cardiac death liver transplantation. Curr Opin Organ Transplant. 2010. 15:316–321.

21. World Health Organization. WHO guiding principles on human cell, tissue and organ transplantation. Transplantation. 2010. 90:229–233.

PDF

PDF ePub

ePub Citation

Citation Print

Print

XML Download

XML Download