Abstract

The aims of this study were; 1) to develop the final version of the Korean Roland-Morris Disability Questionnaire (RDQ), and 2) to compare the responsiveness between the RDQ and the Oswestry Disability Index (ODI) scores in patients having low back pain. The psychometric properties of the final Korean RDQ were evaluated in 221 patients. Among them, 30 patients were reliability tested. Validity was evaluated using an 11-point numerical rating scale (NRS) and the Korean ODI. The receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curve analysis of the RDQ and the ODI was compared in 54 patients with lumbar zygapophyseal (facet) joint pain. There was a moderate relationship between the RDQ and NRS (r = 0.59, P < 0.01) and a strongly positive correlation between the RDQ and the ODI (r = 0.76, P < 0.001). The Korean RDQ with the higher area under the ROC curve showed a better overall responsive performance than did the ODI in patients with lumbar facet joint pain after medial branch radiofrequency neurotomy (P < 0.01). The results of the study present the final version of the Korean RDQ is valid for assessing functional status in a Korean population with chronic low back pain.

Low back pain (LBP) has been a major public health burden and a leading cause of work disability for many years. Among adults in the general population, 70%-85% will experience at least one episode of LBP at some time during their lives (1). Because LBP is not a clinical entity but a symptom with different stages of impairment, disability, and chronicity, physical examination and objective measures of function are at best only weakly associated with outcomes that are more relevant to patients, being symptom relief, daily functioning, and back pain-related disability (2, 3). Assessment of these patient-oriented factors in routine clinical practice is, therefore, essential for clinical research and the assessment of the patients' progress (4).

The Roland-Morris Disability Questionnaire (RDQ) and the Oswestry Disability Index (ODI) have been the 2 most commonly used questionnaires to measure and monitor changes in functional outcome in patients with LBP (5). The RDQ evaluates 24 activity limitations due to LBP, while the ODI consists of 10 items assessing the level of pain interference with physical activities. They are both easy to use and highly correlated, having similar ability to detect functional changes over time (6, 7). However, because of the floor effect of the ODI and the ceiling effect of the RDQ (5), the ODI is suggested to be the better choice in populations with higher disability levels, while the RDQ is recommended for general populations where a number of individuals are at the lower end of the disability spectrum (8, 9).

Although there remain several issues regarding measurement of the psychometric properties understudied (10), it is important to validate the patient-oriented questionnaires in different languages which facilitate the exchange of information in international studies. The ODI and the RDQ have been developed in several languages after comprehensive validity testing to verify what the questionnaire intends to measure. In a previous study, the 9-item Korean version of the ODI, in which questions in section 8 (concerning sex life) was omitted from the original ODI (version 2.0), was validated in patients with lumbar spinal disorders who had higher disability and underwent surgical operations (11). As for the RDQ, a Korean linguistic validation version has been available since 2005 (www.rmdq.org/downloads/korean.pdf), but the psychometric properties has not been examined, yet.

The aims of this study were; 1) to develop the final version of the Korean RDQ with evaluation of its psychometric properties, and 2) to compare the responsiveness between the RDQ and the ODI scores in patients with LBP who have a relatively mild to moderate disability.

The study population consisted of 221 participants (73 men and 148 women). The inclusion criteria were the following: adults aged between 18 and 80 yr, LBP (with or without radiation to leg) in chronic phase (pain lasting more than 3 months). The exclusion criteria were: patients with cognitive deficits discovered during the interview; patients with LBP thought to be caused by infectious disease, malignancy, and visceral diseases; patients with other pathologies causing disabilities or impairments affecting their daily tasks, such as lower-limb amputation or disorders affecting joint mobility.

The assessments included age, gender, weight, height, duration of LBP and the 11-point numerical rating scale (NRS), where 0 represented no LBP and 10 worst imaginable LBP. The 11-point NRS was limited to their LBP. Functional disability was evaluated using the Korean version of the RDQ and the 9-item Korean version of the ODI. In the RDQ, each positive response is scored + 1 and each negative response (question without mark) is scored 0, yielding a final score ranging from 0 (no disability) to 24 (maximum disability). The RDQ did not present unanswered questions or missed information, however, the Korean ODI with 1 question without an answer was corrected as total score/(5 × number of questions answered) × 100%. For assessing responsiveness, the seven-point global perceived effect (GPE) scale was applied for the patients who had been diagnosed with lumbar facet joint pain and had undergone lumbar medial branch radiofrequency (MBRF).

The study was divided in 3 phases.

The procedure included 2 forward translations, comparison among 2 translations and a Korean linguistic validation version previously performed by MAPI Research (www.rmdq.org/downloads/korean.pdf), synthesis, 2 back translations, expert committee examination to produce a pre-final version, testing of the pre-final version, and the development of the final version.

Initially, the two native speakers in Korean language without knowledge of the Korean linguistic validation of the RDQ, performed forward translation of the RDQ from English into Korean independently; one of them was an anesthesiologist familiar with the concept of the questionnaires and the other was a professional translator (an English teacher) who was uninformed of the research.

Then, the expert committee, formed by two translators, two pain clinicians, and a methodologist reviewed the 2 translations and compared them with a Korean linguistic validation version of the RDQ by MAPI Research. After careful review, some modifications in the 7 sentences of the Korean linguistic validation version were decided according to both linguistic and cultural adaptation because 2 newly translated versions were basically similar with a previous Korean linguistic validation version except for the 7 questions. The next step was backward translations performed independently by 2 back translators who were bilingual in Korean and English, but English mother tongues; one of them was a Korean-American physical therapist and the other was a Canadian professional translator. They never had knowledge of the original English version of the RDQ.

Then, the expert committee, in whom 2 backward translators were newly included, reviewed and discussed the original questionnaire and the 2 versions of the translation and came to agreement on the semantic, idiomatic, experiential, and conceptual equivalence between the source and the target version (the prefinal version).

The pre-final version of the RDQ was handed out to 33 patients who, as classified by pain clinicians, were suffering from chronic LBP without much change in symptoms. They were readministered the questionnaire 1 week later during an outpatient visit (10). They were also requested to stop all the interventional procedures newly performed for their low back complaints until the next visit except for their oral medications and ongoing physical therapy. Three patients were not re-administered the follow-up after their first response; two of them visited our clinic more than 3 weeks later from their first response and one underwent an acupunctural procedure for his aggravating low back pain. Patients were also asked to highlight those sentences in each category of the pre-final Korean RDQ which were unclear or those which gave them uncertainty when their first administration of the pre-final Korean RDQ. All the findings from this step were re-evaluated by the expert committee, although no adjustment was further required, and this version was considered the final Korean RDQ version. Therefore, the first data from 30 patients in phase I was included in statistical analysis of Phase II, psychometric properties examination of the final version of the Korean RDQ.

The final Korean RDQ version was applied to 200 new patients. The inclusion criteria and recorded variables were the same as the aforementioned ones. Nine patients did not sign the consent form or refused to participate in this study for personal reasons, therefore, a total of 221 patients, comprised of 30 patients in phase I and 191 patients in phase II, were finally included for psychometric properties examination of the final Korean RDQ version. However, the results of re-tests in 30 patients from Phase I was not included in this phase to avoid carry-over effect of patient responses on the measure.

For the assessment of responsiveness, we selected 58 patients among the 191 patients in Phase II, who were diagnosed (by dual controlled comparative local anesthetic blocks) with lumbar facet joint pain and scheduled for lumbar MBRF. There was no patient from Phase I in Phase III. Before undergoing lumbar MBRF, patients completed baseline NRS, ODI and RDQ which were gathered in Phase II. After lumbar MBRF by using the tunnel vision technique (12), follow-up questionnaires and the seven-point GPE scale were obtained from 54 patients at the 4-week post-MBRF follow-up meeting. In the seven-point GPE scale, patients were asked to score the change in their LBP-caused functional limitations compared to their situations before having undergone lumbar MBRF (Phase II). The scale criteria were: 1 = worse than ever, 2 = much worsened, 3 = slightly worsened, 4 = unchanged, 5 = slightly improved, 6 = much improved, 7 = completely recovered.

The psychometric properties of the final Korean RDQ version were analyzed using SPSS version 17.0 (SPSS, Chicago, IL, USA). A list of the tests follows:

The test-retest reliability (repeatability) was evaluated using the Intraclass Correlation Coefficient (ICC). ICC value above 0.70 is considered acceptable (13). We also used the constructed Bland Altman Plot (14) to visualize the dispersion of the measurements and; the mean of the 2 scores on the RDQ determined at baseline and after 1 week. The differences between these scores were plotted against each other for each subject. Internal consistency reliability (homogeneity) was estimated by means of Cronbach's alpha (15).

The convergent validity was investigated by comparing the response to the RDQ with result of an 11-point NRS at baseline and by correlating the final Korean RDQ and the Korean ODI. For all correlations, Pearson's correlation coefficients were used because the variables were either parametric or normally distributed. A strong correlation was considered to be over 0.60, a moderate between 0.30 and 0.60, and a low (very low) correlation below 0.30 (13).

Potential ceiling and floor effects were measured by assessing the distribution of answers in the categories and calculating the percentage of patients indicating the minimum and maximum possible scores in both questionnaires. Ceiling and floor effects are considered to be present if more than 15% of respondents achieved the lowest or highest possible total score (13).

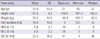

To assess responsiveness we used the 7-point GPE scale which was recommended as the most common external criterion (16), to classify the patients into groups: Those with a score of 6-7 points as "improved", 3-4-5 as "unchanged", and 1-2 as the "deteriorated" group (10). Because the definition of clinical improvement requires a dichotomous variable, we compared the "improved" and the "unchanged" groups by calculating the changes in RDQ before and after lumbar MBRF. The receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curve analysis was performed to determine the optimal cut-off point of RDQ change for improvement. We calculated the area under the curve (AUC) which reflects the ability of the test to discriminate between these two categories of subjects and ranges from 0.5 (no accuracy in distinguishing improved from unchanged) to 1.0 (perfect accuracy). A change in score larger than the optimal cut-off point is taken to be an important change. In addition, by using Z test we compared the 2 ROC curves (ODI change vs. RDQ change) to explore the ability of the questionnaires to detect change with higher diagnostic validity in patients with lumbar facet joint pain.

The study was approved by the institutional review board of Seoul National University Bundang Hospital (IRB No. B-0912-090-007) and carried out on patients with LBP referred to the outpatient clinic of our institution between November 2009 and April 2010. All patients received written and oral information about the study and gave their written consent to participate.

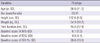

The populations studied in Phase I and II were similar with regard to the parameters measured, therefore, the data of both phases are presented together. Table 1 shows the clinical and demographic characteristics of the study participants.

Some modifications of the 7 sentences in the Korean linguistic validation version of the RDQ were performed by the expert committee after careful reviews with 2 different forward translations; 4 resulted from awkward expressions, 2 from the differences in nuisances, and 1 due to cultural difference. For example, in question No. 7, an easy chair is only used by a few percent of Korean people, the word "easy" was omitted from the statement "Because of my back, I have to hold on to something to get out of an easy chair". Because of the differences in Korean expressive and honorific language, "I am not doing any of the jobs that I usually do around the house" was changed to "I cannot do any of the jobs that I usually do around the house" in question No. 4. In addition, "I try to get other people to do things for me" was clarified to "I try to ask other people to do things for me" in question No 8. There were two severely awkward sentences in the Korean linguistic validation version of the RDQ by MAPI research. Question No. 13 in Korean linguistic validation version of the RDQ by MAPI research was an awkwardly translated sentence, therefore changed into a usual expression in the Korean language. Question No. 18 in the Korean linguistic validation version of the RDQ by MAPI research was wrong, because the original translation confuses time of sleep with quality of sleep and therefore was changed. Finally, there were 2 minor revisions in question No. 9 and 12 in their nuisances.

The test-retest reliability (repeatability) was satisfactory. The ICC, estimated by considering 30 patients on two occasions separated by a mean time interval of 7.76 days (range 4-9 days) was 0.989 (P < 0.001). The constructed Bland and Altman plot for test-retest agreement showed a good reliability (Fig. 1). The internal consistency by means of Cronbach's alpha was 0.879 with coefficients ranging from 0.865 (question No. 4) to 0.886 (question No. 2).

The correlation between the RDQ and the 11-point NRS showed a positive and statistically significant association (r = 0.59, P < 0.001). The assessment of the convergent validity showed a strongly positive correlation between the RDQ and the ODI (r = 0.76, P < 0.001).

The ceiling and floor analysis was performed on the total score of the RDQ. The percentage of respondents who achieved the lowest score (floor effect) was 0.4% (1 patient) and the highest score (ceiling effect) was 0.9% (2 patients). There were no floor and ceiling effects for the RDQ total scores.

The responsiveness of the RDQ was examined by comparing the baseline data and the data collected 1 month after lumbar MBRF in 54 patients (23 men and 31 women) with chronic lumbar facet joint pain. Table 2 presents the characteristics of patients in Phase III. According to the 7-point GPE scale, 32 patients (59.3%) reported to have improved (6-7 points in the 7-point GPE scale), 20 patients (37.0%) to be unchanged (3-5 points in the 7-point GPE scale), and 2 patients (3.7%) to be deteriorated (1-2 points in the 7-point GPE scale). As forementioned, the "improved" and "unchanged" groups were included for analysis. The area under the ROC curve of the RDQ changed after lumbar MBRF was 0.958 (95% confidence interval, 0.86-0.99). The optimal cut-off value was 3.5 with 95.0% in sensitivity and 81.2% in specificity. The RDQ produced a significantly higher area under the receiver operating characteristic curve statistics (AUC = 0.95; 95% CI, 0.85-0.93) than the ODI (AUC = 0.70; 95% CI, 0.56-0.82) in Fig. 2 (P = 0.001).

Our study showed that the Korean RDQ is reliable and valid in a Korean population with chronic LBP. The test-retest reliability of the Korean version of the RDQ was excellent and the internal consistency, assessed by means of Cronbach's alpha was similar to the values present in other studies (17-19). There was a positive and moderate significant correlation between the RDQ and the NRS, coinciding with previous studies (17-19). The convergent validity assessed by means of the correlation between the Korean RDQ and the Korean ODI was 0.758, very similar to the one reported in other studies (17, 19). For responsiveness, in patients with chronic lumbar facet joint pain who underwent lumbar MBRF, the Korean RDQ with the higher area under the ROC curve showed a better overall responsive performance than did the Korean ODI. In those patients, based on the anchor based method using the 7-point GPE scale, the minimal important change of the RDQ was 3.5 points.

For the clinical characteristics, the majority of the participants were female (male:female = 73:148) and they were not selected in this study but allowed in a consecutive way. This female predominance can be explained by two different reasons. One is a general expectation that women are usually considered by society to be responsible for household activities and child rearing, even if the situation is changing and many women are now working in Korea. The other is a special seasonal cause in Korea. We performed this study from November to the next April when the kimchi-making (gimjang) days during the early December and Lunar New Year's holidays in the middle of February was included. Gimjang, which is an annual event especially for Korean women to prepare kimchi having for their family next year, requires heavy labor for women to lift heavy items with bending their spine and knees. Lunar New Year's holiday, which is one of the biggest festive seasons for many Koreans where ancestral rites are performed during family gathering, can be stressful events for women, creating a newly coined term like "holiday syndromes." In these seasons many Korean women suffering from LBP visit their doctors. A few studies also report a high prevalence of LBP in women (20, 21).

If the questionnaire has been well adapted and validated according to linguistic expression and cultural adaptation, comparison of different research findings worldwide can also be possible. Even though there are many scales to measure lumbar disability in Korea, there is no culturally adapted and validated scale available to be used in this population except for the Korean ODI. Previous studies which performed clinical trials in a Korean population were able to use very limited scales for evaluating LBP, such as visual analogue scale (VAS) or NRS (22, 23). We reviewed a previously existing version of the Korean linguistic validation RDQ and culturally corrected some awkward expressions in it. In particular, question 18 "I sleep less well on my back" was wrongly translated as "I sleep less because of my back pain" in the Korean linguistic validation RDQ version, therefore we corrected and clarified it from time of sleep to quality of sleep. The final version of the Korean RDQ is easy to read and makes it appropriate for following-up the progress of individual patients in busy outpatient settings. It is hoped that this culturally equivalent outcome measurements will allow researchers to perform LBP studies reliably in culturally diverse countries.

The use of RDQ is commonly recommended for patients who 0nts with persistent severe disability (5). Although a large number of studies had reported on the responsiveness of the ODI and RDQ compared in a number of different populations (24-26), there was a paucity of research reporting the responsiveness of these measures for patients with mild to moderate LBP, focusing on a single diagnostic entity. This is the first study which compares both scores prospectively in a cohort of patients with chronic lumbar facet joint pain. Our study shows that the RDQ could be a suitable evaluation tool for patients with lumbar facet joint pain. In this study, patients with facet joint pain were chosen because it is assumed to be a relatively mild to moderate disability and of interest to many pain clinicians. However, the generalizability is needed in order to evaluate a responsiveness of this measurement tool.

There are three limitations worth noting in this study. One limitation is the potential for a carry-over effect given that the two administrations for the test-retest reliability were close together in time (mean time interval = 7.76 days), therefore individuals simply remembering answers from the first administration. Although the RDQ is widely recommended for assessing functional status in patients with low back pain and a previous study investigated its measurement properties including the time interval which influence RDQ agreement parameters (10), there is no definitive answer to determining the time interval; longer intervals have limitations as well. The second limitation is the strength of the relationship, particularly between the NRS and ODI which appeared to be a moderate relationship (r = 0.59). Because the NRS and RDQ measure different aspect, function and pain, they are not necessarily the same convergent validity being measured. Finally, a small sample size in phase III (n = 54) for evaluating responsiveness in the final version of the Korean RDQ is the third limitation. Baseline RDQ scores and the way to cluster patients with regard to baseline scores are suggested to influence mainly the optimal cut-off point and responsiveness parameters (10). We had tried to divide two groups according to the median baseline RDQ score (median baseline RDQ score = 9), however, sample sizes in each groups were too small to show generalization and this study was just designed to show the responsiveness of RDQ in a homogenous group with a single disease entity. Therefore, responsiveness should be tested in a randomized clinical trial design or a further follow-up study. In addition, although there is a study which demonstrated that RDQ responsiveness was not influenced by type of intervention (10), further study about the responsiveness would be advantageous.

In conclusion, the results of this study presents that the final version of the Korean RDQ is a reliable and valid tool for assessing the functional status in the Korean population with chronic LBP. It is suggested that the Korean RDQ would be adequate for follow-up assessments of treatments in a busy clinical practice and can be recommended for use in clinical studies of quality of life in patients with LBP.

Figures and Tables

Fig. 1

Bland Altman plot for test-retest reliability of the Roland-Morris Disability Questionnaire: mean-against-difference graph. For each subject (n = 30), the mean of the 2 scores on the Korean RDQ at baseline (T0) and after 4-9 days (T1) and the difference between these time points (T1-T0) are plotted against each other.

Fig. 2

Area under the receiver operating characteristic curves for the Roland-Morris Disability Questionnaire and Oswestry Disability Index at one month.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors thank Mr. Graham Love, International Affairs Officer at Kyung Hee University Hospital at Gangdong for supervising the forward and backward translations of RDQ.

AUTHOR SUMMARY

Psychometric Characteristics of the Korean Version of the Roland-Morris Disability Questionnaire

Jeeyoun Moon, Yong Chul Kim, Soo Young Park, Sang Chul Lee, Seung Pyo Choi, Francis Sahngun Nahm, Pyung Bok Lee, Eui Kyung Goo and Jong-Man Kang

Linguistically and culturally well adapted and validated questionnaire allows comparison of different research findings worldwide. Among many scales to measure lumbar disability in Korea, the Korean Oswestry Disability Index has been regarded as a reliable questionnaire. The results of this study presents that the final version of the Korean Roland-Morris Disability Questionnaire (RDQ) is also a reliable and valid tool for assessing the functional status in the Korean population with chronic low back pain. It is suggested that the Korean RDQ would be adequate for follow-up assessments of treatments in a busy clinical practice and for clinical studies of quality of life in patients with low back pain.

References

1. Andersson GB. Epidemiological features of chronic low-back pain. Lancet. 1999. 354:581–585.

2. Deyo RA, Battie M, Beurskens AJ, Bombardier C, Croft P, Koes B, Malmivaara A, Roland M, Von Korff M, Waddell G. Outcome measures for low back pain research. A proposal for standardized use. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 1998. 23:2003–2013.

3. Mannion AF, Junge A, Taimela S, Müntener M, Lorenzo K, Dvorak J. Active therapy for chronic low back pain: part 3. factors influencing self-rated disability and its change following therapy. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 2001. 26:920–929.

4. Airaksinen O, Brox JI, Cedraschi C, Hildebrandt J, Klaber-Moffett J, Kovacs F, Mannion AF, Reis S, Staal JB, Ursin H, Zanoli G. COST B13 Working Group on Guidelines for Chronic Low Back Pain. Chapter 4. European guidelines for the management of chronic nonspecific low back pain. Eur Spine J. 2006. 15:Suppl 2. S192–S300.

5. Roland M, Fairbank J. The Roland-Morris disability questionnaire and the oswestry disability questionnaire. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 2000. 25:3115–3124.

6. Kopec JA, Esdaile JM. Functional disability scales for back pain. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 1995. 20:1943–1949.

7. Stratford PW, Binkley J, Solomon P, Gill C, Finch E. Assessing change over time in patients with low back pain. Phys Ther. 1994. 74:528–533.

8. Bombardier C. Outcome assessments in the evaluation of treatment of spinal disorders: summary and general recommendations. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 2000. 25:3100–3103.

9. Kopec JA, Esdaile JM, Abrahamowicz M, Abenhaim L, Wood-Dauphinee S, Lamping DL, Williams JI. The Quebec back pain disability scale: measurement properties. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 1995. 20:341–352.

10. Demoulin C, Ostelo R, Knottnerus JA, Smeets RJ. What factors influence the measurement properties of the Roland-Morris disability questionnaire? Eur J Pain. 2010. 14:200–206.

11. Kim DY, Lee SH, Lee HY, Lee HJ, Chang SB, Chung SK, Kim HJ. Validation of the Korean version of the oswestry disability index. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 2005. 30:E123–E127.

12. Gofeld M, Faclier G. Radiofrequency denervation of the lumbar zygapophysial joints: targeting the best practice. Pain Med. 2008. 9:204–211.

13. Terwee CB, Bot SD, de Boer MR, van der Windt DA, Knol DL, Dekker J, Bouter LM, de Vet HC. Quality criteria were proposed for measurement properties of health status questionnaires. J Clin Epidemiol. 2007. 60:34–42.

14. Bland JM, Altman DG. Statistical methods for assessing agreement between two methods of clinical measurement. Lancet. 1986. 1:307–310.

15. Cronbach LJ. Coefficient alpha and the internal structure of tests. Psychometrika. 1951. 16:297–334.

16. Lauridsen HH, Hartvigsen J, Korsholm L, Grunnet-Nilsson N, Manniche C. Choice of external criteria in back pain research: does it matter? Recommendations based on analysis of responsiveness. Pain. 2007. 131:112–120.

17. Scharovsky A, Pueyrredón M, Craig D, Rivas ME, Converso G, Pueyrredón JH, Salvat F, Alzúa O. Cross-cultural adaptation and validation of the Argentinean version of the Roland-Morris disability questionnaire. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 2008. 33:1391–1395.

18. Opara J, Szary S, Kucharz E. Polish cultural adaptation of the Roland-Morris questionnaire for evaluation of quality of life in patients with low back pain. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 2006. 31:2744–2746.

19. Mousavi SJ, Parnianpour M, Mehdian H, Montazeri A, Mobini B. The Oswestry disability index, the Roland-Morris disability questionnaire, and the Quebec back pain disability scale: translation and validation studies of the Iranian versions. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 2006. 31:E454–E459.

20. Johansson E, Lindberg P. Subacute and chronic low back pain. Reliability and validity of a Swedish version of the Roland and Morris disability questionnaire. Scand J Rehabil Med. 1998. 30:139–143.

21. Mâaroufi H, Benbouazza K, Faïk A, Bahiri R, Lazrak N, Abouqal R, Amine B, Hajjaj-Hassouni N. Translation, adaptation, and validation of the Moroccan version of the Roland Morris disability questionnaire. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 2007. 32:1461–1465.

22. Park CH. Comparison of effectiveness of CT vs C-arm guided percutaneous radiofrequency lumbar facet rhizotomy. Korean J Pain. 2010. 23:137–141.

23. Park SB, Kim MC, Ha SI. The effects of epidural anesthesia in elderly patients during single-level lumbar microdiscectomy. Korean J Spine. 2010. 7:24–27.

24. Davidson M, Keating JL. A comparison of five low back disability questionnaires: reliability and responsiveness. Phys Ther. 2002. 82:8–24.

25. Frost H, Lamb SE, Stewart-Brown S. Responsiveness of a patient specific outcome measure compared with the Oswestry disability index v2.1 and Roland and Morris disability questionnaire for patients with subacute and chronic low back pain. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 2008. 33:2450–2457.

26. Beurskens AJ, de Vet HC, Köke AJ. Responsiveness of functional status in low back pain: a comparison of different instruments. Pain. 1996. 65:71–76.

PDF

PDF ePub

ePub Citation

Citation Print

Print

XML Download

XML Download