Abstract

This report is about the case of gastritis associated with capillariasis. The patient was a 52-yr-old Korean woman who occasionally ate raw fish and chicken. She complained of mild abdominal pain and nausea, but not diarrhea. An endoscopic examination revealed an exudative flat erosive change on the gastric mucosa of the antrum. She was microscopically diagnosed as chronic gastritis with numerous eosinophil infiltrations. The sectioned worms and eggs in mucosa were morphologically regarded as belonging to the genus Capillaria. This is the first case of gastric capillariasis reported in the Republic of Korea.

The members of the genus Capillaria that have been recorded in human beings are; Capillaria hepatica, C. aerophila, and C. philippinensis. These three species cause hepatic, pulmonary, and intestinal capillariasis, respectively (1, 2). Moreover, cases of human infection by C. philippinensis appear to be spreading geographically, and in particular, intestinal capillariasis is being increasingly reported in Asia (3). In the Republic of Korea, two indigenous and three imported cases of intestinal capillariasis have been reported since 1993 (4, 5).

Capillaria species parasitize various parts of the host alimentary system, mainly the small intestine and stomach, but rarely the esophagus and rectum (6). Although the stomach is an appropriate habitat for some Capillaria species, no case of human stomach infection has been reported. Therefore, physicians and parasitologists do not consider Capillaria species as an etiologic agent of gastritis in man. This paper describes our experience with an unusual case of human gastric capillariasis.

On October 31, 2006, a 52-yr-old Korean woman attended the outpatient clinic for a health checkup. She lived in Jangheung-gun, Jeollanam-do, a county located on the south coast. She recalled eating raw fish, i.e., gizzard shad (Konosirus punctatus), purple pike conger (Muraenesox cinereus), and snake-head (Channa argus). The former two species were eaten on August 10, 2006 and the latter during mid-August, 2005. She had also eaten raw chicken, which she had slaughtered, at the beginning of September, 2006. She had not traveled to any foreign country.

According to her medical history, she had been diagnosed as having hypertension in 2005. About seven years previously, she had experienced episodes of abdominal pain, and was attributed to gastritis by a local clinic. When she presented at our clinic for a health checkup, she complained of abdominal pain of approximately 3 months duration, which was accompanied sometimes by nausea, but not by vomiting, diarrhea, borborygmus, fever, or weight loss. In order to relieve this symptom, she had taken some antacids, which were obtained over-the-counter, several times a month before presentation. She also had an itching rash of one week's duration that primarily involved a forearm. On physical examination, her pulse rate was regular and her blood pressure was 138/95 mmHg. No abdominal mass was palpated, and the liver and spleen were not enlarged. The blood biochemistry data was as follows: hemoglobin 13.7 g/dL, serum glucose 102 mg/dL, GOT 23 IU/L, γ-GPT 15 IU/L, and total cholesterol 189 mg/dL. Routine urine analysis findings were in the normal range. Stool occult blood was negative, and chest radiography findings were normal. Since a parasitic infection was not considered at that time, no blood eosinophil count or stool examination for nematodes was performed.

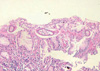

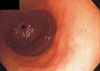

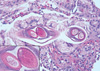

By upper gastrointestinal endoscopy, the esophagus and duodenum appeared grossly normal. However, at the posterior wall of the antrum, the gastric mucosa showed an exudative flat erosive change (Fig. 1). Microscopically, the biopsied specimen disclosed mild mucosal destruction with an irregular surface and focal surface erosion. Multiple sections of adult female nematodes were observed, usually in the superficial gastric mucosa. The worms lived in the epithelial layer of the glands and in adjacent tissues of the lamina propria, and had caused inflammatory cell infiltration (Fig. 2). Many eosinophils were observed around the worms (Fig. 3). In cross sections through the uterus, female worms were 52.5-62.5 µm (mean 57.6 µm) in diameter. Stichosome was found in the anterior portion of worms in longitudinal sections (Fig. 4). The uterus was prominent and occupied most of the pseudocoelomic cavity (Fig. 2, 3). It usually contained several eggs, which had a striated shell and inconspicuous flattened bipolar plugs (Fig. 3, 5). No developing larvae were observed in any uterine or extra-uterine eggs. In tangential-sectioned eggs, eggshell striations formed a network, which resembled a net with irregular meshes (Fig. 3). Eggs dimensions were 57.2-60.0×24.0-30.5 µm (average 58.5×26.0 µm). Based on the microscopic features of the worms and eggs, the nematodes were assigned to Capillaria species. We recommended albendazole administration, at 800 mg/day for two weeks. However, during this treatment no discharged worms or eggs were detected in feces. The gastric pain disappeared in two weeks, and after one year on medication the patient was healthy.

A definitive diagnosis of gastrointestinal capillariasis is made by identifying eggs or adults in stools, biopsy specimens of infected organs, or by autopsy (1, 7). In the present case, worms were found to have characteristic stichosome in esophageal sections. Cross-sectioned female adult worms were ca. Fifty eight micrometer wide in the uterine portion. This small diameter was enough to allow them to be differentiated from C. aerophila and C. hepatica, and was most similar to that reported for C. philippinensis (1, 2, 8). Capillarid's eggs are operculated with inconspicuous flattened bipolar plugs, and have a striated eggshell (1, 2). In the present case, eggshell morphology was similar to that of genus Capillaria. However, egg size was not identical to any reported species of human capillariasis. As compared with three species of human capillariasis, egg length was similar to that of C. hepatica (51-68 µm) (2), but diameters were not. In fact, egg diameters in the described case were between those of C. philippinensis (21 µm) and C. hepatica (30-35 µm) (2, 8). Consequently, morphometric observations provided a presumptive diagnosis of infection by Capillaria genus. However, since no whole worm was isolated, it was very difficult to extend the identification to the species level.

The problem of species identification is compounded by variations in host specificity and habitat. Adult C. philippinensis worms in the human digestive tract are usually found in the mucosa of the small intestine from the lower third of the duodenum to the proximal third of the ileum, and although they have been found in the luminal fluid of the larynx, esophagus, stomach, and colon this was attributed to postmortem migration (7). Therefore, true gastric capillariasis has not been reported in man. However, the stomach is a common habitat in cases of animal capillariasis (6). Thus, accidental infection by an animal capillarid is a possibility in the present case.

It is well known that intestinal Capillaria worms usually cause severe pathologic changes, such as, loss of a villous architecture, crypt abscess composed of eosinophils, vascular congestion, and focal hemorrhage (1, 4, 7). In the present case, the most prominent finding was of gastritis with eosinophilic infiltration. Similar pathologic features were observed in the biopsied specimen of an accidental gastric infection caused by another trichinellidae, Trichuris tichiura (9). It revealed mild superficial gastritis with eosinophil infiltration into the mucosa and submucosa. In general, the severity of mucosal damage caused by any gastrointestinal helminth is proportional to the number of worms present. In the present case, no egg was found to be developing into a larva, which implies that autoinfection and hyperinfection were not possible (1). Thus, it is suspected that the pathogenicities of intestinal and gastric capillariasis differ.

Some fresh- or brackish-water fish are considered to be natural intermediate hosts for various Capillaria species (1, 2). The source of capillariasis infection was unclear in the present case. Our patient had consumed raw freshwater fish (about one year previously) and brackish-water fish (about three months previously). Thus, in view of the onset of her gastric symptom, the two species of brackish-water fish, namely, the gizzard shad or the purple pike conger, which were both caught in coastal waters, were probably responsible. These two fish are commonly eaten raw in Korea. Another possible source of infection was the raw chicken meat she had eaten two months previously. Some fish-eating birds, including the chicken, are potential definitive hosts and autoinfection has also been reported in birds (10).

In conclusion, we describe an accidental gastric infection caused by Capillaria species. It was probably due to the consumption of raw fish. An endoscopic biopsy revealed superficial gastritis with eosinophil infiltration. Unlike intestinal capillariasis, gastric capillariasis extremely rare in man. Its clinical symptoms are nonspecific, and for these reasons the infection is easily overlooked by patients and even by physicians. However, the possibility of gastric involvement should be carefully considered in gastritis patients infected with Capillaria species.

Figures and Tables

Fig. 2

Three sectioned worms in the superficial portion of the gastric mucosa. Adult female worms with eggs in the uterus had invaded the epithelial layer of the glands and adjacent tissues of the lamina propria causing inflammatory cell infiltration (H&E stain, ×100).

References

2. Beaver PC, Jung RC, Cupp EW. Clinical Parasitology. 1984. Philadelphia: Lea & Febiger;231–252.

3. Hong ST, Cross JH. Arizono N, Chai JY, Nawa Y, Takahashi Y, editors. Capillaria philippinensis infection in Asia. Asian Parasitology. 2005. vol. 1 Food-borne helminthiasis in Asia. Chiba: Federation of Asian Parasitologists;225–229.

4. Lee SH, Hong ST, Chai JY, Kim WH, Kim YT, Song IS, Kim SW, Choi BI, Cross JH. A case of intestinal capillariasis in the Republic of Korea. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 1993. 48:542–546.

5. Hong ST, Kim YT, Choe G, Min YI, Cho SH, Kim JK, Kook J, Chai JY, Lee SH. Two cases of intestinal capillariasis in Korea. Korean J Parasitol. 1994. 32:43–48.

6. Okulewicz A, Zalesny G. Biodiversity of Capillariinae. Wiad Parazytol. 2005. 51:9–14.

7. Fresh JW, Cross JH, Reyes V, Whalen GE, Uylangco CV, Dizon JJ. Necropsy findings in intestinal capillariasis. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 1972. 21:169–173.

8. Chitwood MB, Valesquez C, Salazar NG. Capillaria philippinensis sp. n. (Nematoda: Trichinellida), from the intestine of man in the Philippines. J Parasitol. 1968. 54:368–371.

PDF

PDF ePub

ePub Citation

Citation Print

Print

XML Download

XML Download