Abstract

A primary benign schwannoma of the liver is extremely rare. Only nine cases have been reported in the medical literature worldwide and no case has been reported in Korea previously. A 36-yr-old woman was admitted to our hospital with vague epigastric pain. The ultrasound and computed tomography scan revealed a multi-septated cystic mass in the right lobe of the liver. The mass was resected; it was found to be a 5 × 4 × 2 cm mass filled with reddish yellow fluid. The histological examination confirmed the diagnosis of a benign schwannoma, proven by positive immunoreaction with the neurogenic marker S-100 protein and a negative response to CD34, CD117 and smooth muscle actin. This is the first report of a benign schwannoma of the liver parenchyma in a Korean patient.

A schwannoma is a benign nerve sheath tumor that originates from the Schwann cells of the nerve sheath. It occurs usually during the third to sixth decade of life. Although it can develop in any part of the body, the most common sites include the head, neck and flexor surfaces of the extremities. A schwannoma can develop infrequently in the gastrointestinal tract or retroperitoneal cavity as well. However, a primary benign schwannoma of the liver is extremely rare. Only nine cases have been reported in the medical literature to date (1-8). Although a benign schwannoma of the porta hepatis has been reported in Korea (9), there is no previous report of a case involving the liver parenchyma. We herein describe a case of a benign schwannoma of the liver parenchyma, which is the first report in a Korean patient diagnosed after surgical resection, with a review of the literature.

A 36-yr-old woman was referred to our hospital for further evaluation of a 4.5 cm-sized mass in the liver detected by abdominal ultrasonography at a private clinic. The patient initially presented to the clinic with vague and constant epigastric discomfort for two weeks. No specific findings were noted in the medical, social and family history.

On physical examination, the vital signs on admission were a blood pressure (BP) of 110/80 mmHg, heart rate (HR) 78/min, respiratory rate (RR) 20/min and body temperature (BT) 36.2℃. The patient appeared alert and well. There were no neck lymph nodes palpable. The patient's sclerae were anicteric and the conjunctivae were not anemic. Physical examination of the chest, back and extremities were unremarkable. Physical examination of the abdomen showed normoactive bowel sounds, no tenderness or rebound tenderness of the epigastrium, and no hepatomegaly or splenomegaly. There were no café-au-lait spots or cutaneous neurofibromas suggestive of von Recklinghausen's disease. The laboratory findings on admission were as follows: the hemoglobin was 13.4 g/dL, the peripheral white blood cell count was 4,590/µL and the platelet count was 173,000/µL. The total bilirubin was 0.4 mg/dL, the alkaline phosphatase (ALP) was 61 IU/L, the aspartate aminotransferase (AST) was 17 IU/dL, and the alanine aminotransferase (ALT) was 17 IU/dL. The serum sodium was 140.3 mM/L, the serum potassium was 4.2 mM/ L and the serum chloride was 102 mM/L. The blood urea nitrogen (BUN) was 12.6 mg/dL and the creatinine was 0.7 mg/dL.

An ultrasound of the liver revealed a round multi-septated irregular hypoechoic mass in the right lobe (Fig. 1). A computed tomography (CT) of the abdomen was obtained for further analysis of the mass. The CT scan demonstrated a 4.5 cm-mass in the right lobe of the liver at segment V with internal septa and hyperdense solid elements (Fig. 2). There were no enlarged lymph nodes found near the mass and no other abnormal findings on the abdominal CT scan. We suspected a biliary cystic neoplasm such as a biliary cystadenoma or adenocarcinoma. The ultrasound-guided needle biopsy obtained a specimen with spindle cells of benign appearance and clusters of hepatocytes. The overall impression was a benign mesenchymal tumor of the liver.

With the suspicion of a benign mesenchymal tumor of the liver, we proceeded to a segmentectomy. The gross findings were a round, cystic and approximately 5 × 5 cm mass. The patient's postoperative course was uneventful. The surgical specimen was composed of an encapsulated mass of 5 × 4 × 2 cm with adjacent normal liver parenchyma (Fig. 3). Microscopic examination revealed a spindle cell tumor with cells arranged in whorls in a storiform pattern surrounded by a fibrous capsule and a mixture of two growth patterns, Antoni A and Antoni B (Fig. 4). In the Antoni A pattern of growth, elongated cells were arranged in areas of moderate to high cellularity with little stromal matrix. In the Antoni B pattern of growth, the tumor was less densely cellular, had a loose meshwork of cells, as well as microcysts and myxoids changes. Atypias or mitoses of cells were not recognized. The immunohistochemical staining showed a strongly positive S-100 protein reaction (Fig. 5). However, CD34, CD117 and smooth muscle actin were all negative.

Based on the above findings, the diagnosis of a primary benign schwannoma of the liver parenchyma was made. The patient remained healthy and free from recurrence during the 18 months of follow-up.

A schwannoma is a benign mesenchymal tumor that originates from Schwann cells in the peripheral nerves. The tumor is associated with neurofibromatosis in about 50% of cases. Malignant transformation of these tumors is very rare (10). They grow very slowly and are well encapsulated in most cases. Schwannomas are usually smaller than 5 cm at diagnosis (11). Larger schwannomas have a tendency to undergo secondary degeneration such as pseudocystic regression, hemorrhage and calcification.

The incidence of a schwannoma in the gastrointestinal (GI) tract is very low; it accounts for about 2-6% of all mesenchymal tumors that develop in the GI tract (12). There are several reports of benign schwannomas in the stomach, duodenum, rectum, and retroperitoneum. However, there is no previous report of a benign schwannoma of the liver parenchyma in a Korean patient.

The hepatobiliary nerves originate from the hepatic plexus in the hilum. A schwannoma of the liver can originate from a variety of hepatic sympathetic and parasympathetic nerves distributed among the intralobular connective tissues and hepatic arteries (13). The schwannoma in our case was surrounded by normal hepatic parenchyma. Thus, we diagnosed the tumor as a benign primary schwannoma of the liver.

In 1993, Hytiroglou et al. reported the first primary benign hepatic schwannoma diagnosed after surgical resection (3). We reviewed the clinical characteristics, location, size and secondary degeneration of primary benign schwannomas and the findings are shown in Table 1 (1-8). They were found in eight women and two men. The age of onset was from 38 to 70 yr, and the mean age of onset was 57.2 yr. Most patients complained of pain or discomfort in the upper abdomen or epigastrium. Two patients were asymptomatic. Tumors were located in the right lobe of the liver in five cases and in the left lobe in four cases. The maximal diameter of the tumors ranged from 4 cm to 30 cm. The mean diameter was 18.9 cm. In most cases, the tumors had secondary degeneration. Smaller tumors, approximately 4 or 5 cm in diameter, were less likely to have secondary degeneration. Radiological findings showed degenerative changes with cyst-like characteristics, calcification and hemorrhage as well as normal liver tissue surrounding the encapsulated mass, which was well demarcated, round or ovoid (14). In comparing our case with other cases shown Table 1, the clinical characteristics, location and secondary degeneration of the tumors are similar. However, the tumor size was much smaller than average.

Generally, a plain CT depicts a schwannoma as a nonhomogenous area; an enhanced CT shows the margins clearly and the inside appears as an irregular pattern (6). A definitive diagnosis of a hepatic schwannoma by radiological methods is difficult because it is such a rare finding. Therefore, pathological examination is essential for the diagnosis.

Microscopic examination shows spindle cells like other stromal tumors. The histological diagnosis of a benign schwannoma is usually a simple procedure with standard Hematoxilin-Eosin staining. The distinction between a schwannoma and other spindle cell tumors or neurofibromas is based on the presence of a true capsule and Antoni A and Antoni B findings in the schwannoma (11). The type A area is dense and cellular, but the type B area is hypocellular. Immunohistochemical staining is diffusely and strongly positive for S-100 protein in a schwannoma consistent with the finding of a nerve sheath tumor. The tumor is also positive for the glial fibrillary acidic protein and CD57 (Leu 57) (15). Even though a few gastrointestinal stromal tumors are positive for S-100, they are also positive for either CD34 or CD117. However, a schwannoma is negative for both CD34 and CD117. A leiomyoma would be negative for S-100 and positive for desmin or smooth muscle actin (16).

The treatment for a benign primary schwannoma is a simple excision. The complete excision of the tumor is curative and most cases do not relapse; additional treatments are not necessary. The overall prognosis is very good (17).

In conclusion, we report the first case of a primary schwannoma of the liver parenchyma in Korea. The diagnosis was established after surgical resection of the tumor that was identified to have spindle cells with Antoni A and Antoni B areas and was strongly positive for the S-100 protein but negative for CD34, CD117 and smooth muscle actin.

Figures and Tables

Fig. 1

Ultrasound findings of the mass. A 4.5-cm sized round hypoechoic mass with multiple central echogenic bands in the right lobe of the liver (segment V).

Fig. 2

Abdominal computed tomography shows a 5 cm smooth margined low-attenuating mass in the right lobe of liver (segment V), containing multiple central septations.

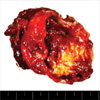

Fig. 3

A photograph showing the cut section of the tumor: The specimen was 5 × 4 × 2 cm. A multi-septated cyst that was previously opened, measuring 4 × 4 cm. The cyst was 1 cm from the resection margin. The cyst contained 10 soft tissues. The wall thickness measured 0.4 cm.

Fig. 4

(A) Spindle cell tumor with a mixture of two growth patterns, Antoni A and Antoni B, is seen. In the Antoni A pattern of growth, elongated cells were arranged in areas of moderate to high cellularity (black arrow). In the Antoni B pattern of growth, the tumor was less densely cellular, had a loose meshwork of cells, as well as microcysts and myxoids changes (red arrow) (H&E, ×100). (B) Spindle cell tumor with cells arranged in whorls in a storiform pattern is seen (H&E, ×200).

References

1. Pereira Filho RA, Souza SA, Oliveira Filho JA. Primary neurilemmal tumour of the liver: case report. Arq Gastroenterol. 1978. 15:136–138.

2. Bekker GM. Neurofibroma of the liver. Sov Med. 1982. 10:120–121.

3. Hytiroglou P, Linton P, Klion F, Schwartz M, Miller C, Thung SN. Benign schwannoma of the liver. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 1993. 117:216–218.

4. Heffron TG, Coventry S, Bedendo F, Baker A. Resection of primary schwannoma of the liver not associated with neurofibromatosis. Arch Surg. 1993. 128:1396–1398.

5. Yoshida M, Nakashima Y, Tanaka A, Mori K, Yamaoka Y. Benign schwannoma of the liver: a case report. Nippon Geka Hokan. 1994. 63:208–214.

6. Wada Y, Jimi A, Nakashima O, Kojiro M, Kurohiji T, Sai K. Schwannoma of the liver: report of two surgical cases. Pathol Int. 1998. 48:611–617.

7. Flemming P, Frerker M, Klempnauer J, Pichlmayr R. Benign schwannoma of the liver with cystic changes misinterpreted as hydatid disease. Hepatogastroenterology. 1998. 45:1764–1766.

8. Kapoor S, Tevatia MS, Dattagupta S, Chattopadhyay TK. Primary hepatic nerve sheath tumor. Liver Int. 2005. 25:458–459.

9. Park MK, Lee KT, Choi YS, Shin DH, Lee JY, Lee JK, Paik SW, Ko YH, Rhee JC. A case of benign schwannoma in the porta hepatis. Korean J Gastroenterol. 2006. 47:164–167.

10. Ducatman BS, Scheithauer BW, Piepgras DG, Reiman HM, Ilstrup DM. Malignant peripheral nerve sheath tumors. A clinicopathologic study of 120 cases. Cancer. 1986. 57:2006–2021.

11. Brennan MF, Singer S, Maki RG, O'sullivan B. DeVita VT, Hellman S, editors. Soft tissue sarcoma. Cancer: Principles & practice of oncology. 2000. 7th edition. Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins;1595.

12. Lantz PE, Listrom MB. Fenoglio-Preiser CM, Noffsinger AE, Stemmermann GN, editors. Gastrointestinal mesenchymal neoplasms. Gastrointestinal pathology. 2002. 2nd edition. Philadelphia: Lippincott-Raven;1185–1188.

13. Williams PL, Warwick R, Dyson M, Bannister LH, editors. Gray's anatomy. 1989. 37th edition. New York: Churchill Livingstone;1165. 1390. 1395.

14. Cohen LM, Schwartz AM, Rockoff SD. Benign schwannomas: pathologic basis for CT inhomogeneities. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 1986. 147:141–143.

15. Daimaru Y, Kido H, Hashimoto H, Enjoji M. Benign schwannoma of the gastrointestinal tract: a clinicopathologic and immunohistochemical study. Hum Pathol. 1988. 19:257–264.

16. Miettinen M, Lasota J. Gastrointestinal stromal tumors: review on morphology, molecular pathology, prognosis, and differential diagnosis. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2006. 130:1466–1478.

17. Enzinger FM, Weiss SW. Enzinger FM, Weiss SW, editors. Benign tumors of peripheral nerves. Soft tissue tumors. 1995. 3rd edition. St. Louis: Mosby;829–842.

PDF

PDF ePub

ePub Citation

Citation Print

Print

XML Download

XML Download