Abstract

Acute interstitial pneumonia (AIP) is a rapidly progressive condition of unknown cause that occurs in a previously healthy individual and produces the histologic findings of diffuse alveolar damage. Since the term AIP was first introduced in 1986, there have been very few case reports of AIP in children. Here we present a case of AIP in a 3-yr-old girl whose other two siblings showed similar radiologic findings. The patient was confirmed to have AIP from autopsy showing histological findings of diffuse alveolar damage and proliferation of fibroblasts. Her 3-yr-old brother was also clinically and radiologically highly suspected as having AIP, and the other asymptomatic 8-yr-old sister was radiologically suspected as having AIP.

Acute interstitial pneumonia (AIP) is an idiopathic lung disease characterized by rapidly progressive respiratory failure occurring in patients without pre-existing systemic or lung diseases with diffuse alveolar damage histologically (1, 2). Since the term "acute interstitial pneumonia" was first introduced in 1986 (3, 4), some reported case reviews of AIP (4-8), with only 2 pediatric case reports (3, 8). This is a case report of a 3-yr-old girl diagnosed as having AIP from autopsy, whose two other siblings showed the similar radiological findings. This is the first case report of AIP in three children from the same family; one of them was histologically confirmed, another was clinically and radiologically quite similar, and the other was radiologically suspected as having AIP.

A 3-yr-old previously healthy girl presented with progressive dyspnea and chest discomfort. Over the preceding 1 week, she had been admitted to a local general hospital for a sudden onset of dyspnea followed by 3 weeks of upper respiratory symptoms, mild rhinorrhea and dry cough without fever. Her 2-yr-old brother showed the same clinical symptoms presented at the same time; however, she did not have any other known familial history of certain disease. There was no evidence of systemic infection, immune suppression, exposure to toxic agents, pre-existing lung disease, or collagen-vascular disease.

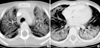

On physical examination, she showed an acutely ill-looking appearance. Her body temperature was 37.0℃ and blood pressure was 105/75 mmHg. She showed tachypnea (respiratory rate 48/min) and chest wall retraction, and was requiring 5 L oxygen with face mask. Crackles were heard bilaterally in the bases of her lungs. There were bilateral ground-glass opacification on simple chest radiograph and also bilateral ground-glass attenuation with diffuse alveolar consolidation on chest high-resolution computed tomography (HRCT) (Fig. 1). Arterial blood gas analysis gave pH 7.40, PaO2 88 mmHg, PaCO2 46 mmHg, SaO2 96% (5 L/min of oxygen with face mask), and the white blood cell count was 9,330/µL with 78% neutrophils. C-reactive protein was negative, and other chemistry results were all within normal limits. Blood and sputum culture did not show any abnormal findings. Viral investigations including respiratory syncytial virus, adenovirus, influenza, parainfluenza, cytomegalovirus, Ebstein-Barr virus, herpes simplex virus, and evaluation for Mycoplasma pneumoniae showed negative results. Rheumatoid factor and anti-nuclear antibody were both negative.

Under a presumptive diagnosis of interstitial lung disease, intravenous antibiotics and dexamethasone were administered. Despite these treatment and conservative management with oxygen supply, her respiratory difficulty was aggravated. She presented with severe dyspnea and chest discomfort with pneumomediastinum and subcutaneous emphysema on chest radiograph. Pneumomediastinum was aggravated and resulted in pulmonary hemorrhage. Because of ongoing hypoxemia and decreased mentality, endotracheal intubation was performed at 13th hospital day. The patient died on the 14th day of admission after four times of cardiac arrest.

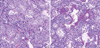

The patient underwent autopsy. The histopathologic findings on autopsy of the lungs revealed diffusely thickened alveolar septal interstitium by uniform, organizing loose fibrosis and foci of hyaline membranes as well as prominent interstitial and alveolar edema with focal hyperplasia of type II pneumocytes, which were indicative of organizing diffuse alveolar damage (DAD) and episodes of acute lung injuries (Fig. 2).

Her 2-yr-old brother showed a same clinical course with diffuse bilateral ground-glass opacities on his HRCT and also died after 4 weeks of intensive care due to respiratory failure aggravated by pneumothorax and subcutaneous emphysema. It was unable to undergo any follow-up HRCT, lung biopsy, or bronchoalveolar lavage because of his critical condition. Their 8-yr-old sister had no symptoms but underwent HRCT for screening, which showed a mild degree of bilateral ground-glass opacities. Her pulmonary function test (PFT) revealed patterns of restrictive lung disease. However, her follow-up HRCT and PFT showed improvement after five weeks of oral steroid administration.

In 1944, Hamman and Rich initially described four previously healthy patients with fatal fulminant lung disease that, on autopsy, was characterized as extensive pulmonary fibrosis (8). In 1986, Katzenstein and coworkers introduced the term "AIP" to describe eight patients characterized by idiopathic interstitial lung disease causing a rapid onset of respiratory failure, which was distinguished from other chronic forms of interstitial pneumonia (3). Since then, some reports have reviewed the cases of AIP (4-8), but among them, there were only 2 pediatric cases reports (4, 8) showing a much lower incidence then in adult.

Clinical manifestation of AIP usually begins with prodromal 'flu-like' upper respiratory infection symptoms, followed by rapid progression of dyspnea and respiratory failure that requires mechanical ventilation. In our case, the patient presented the same clinical course as in the previously reviewed cases; beginning with mild cough and rhinorrhea, which was aggravated into respiratory failure requiring mechanical ventilation.

Most of the cases reported as AIP had extensive bilateral air-space opacification with sparing of costophrenic angles on their chest radiograph. As AIP moves from exudative to organizing stage, the radiograph shows less consolidation and presents a ground-glass appearance with irregular linear opacities (7). The most common CT findings in AIP patients are diffuse ground-glass attenuation with a mosaic pattern and consolidation (often in the dependent regions of the lungs) (2). In the early exudative phase, the lung shows areas of ground-glass attenuation that are most often bilateral and patchy, with areas of focal sparing of lung lobules giving a geographic appearance. The later, organizing stage of AIP is associated with distortion of bronchovascular bundles and traction bronchiectasis and cysts.

In our case, there was bilateral diffuse consolidation of lungs with peripheral sparing zones on chest radiograph, and chest HRCT showed diffuse ground-glass opacities and consolidations with sparing zones in the peripheral portion of each lobe, suggesting the early exudative phase of AIP. This study was performed at the beginning of the patient's respiratory difficulty, but follow-up HRCT was not performed due to the patients critical condition. Even though we could not undergo another follow-up HRCT, her chest radiograph showed an increase of bilateral haziness and findings of spontaneous pneumomediastinum and subcutaneous emphysema with bronchiectatic changes, suggesting a progression into the late organizing phase. Her 2-yr-old brother also showed same findings on chest CT, which was aggravated into bronchiectatic changes and pneumomediastinum on his chest radiograph. Their 8-yr-old sister who did not have any symptoms only showed a mild degree of bilateral ground-glass opacities without progression to bronchiectactic changes of lung parenchyma.

The histologic findings of AIP include the features of acute and/or organizing phases of DAD. The exudative phase shows edema, hyaline membranes, and interstitial acute inflammation (7). In the organizing phase, organizing fibrin, loose organizing fibrosis within alveolar lumens with incorporation within alveolar septa, and type II pneumocyte hyperplasia are seen (2). In this case, the patient underwent autopsy and histologic finings showed hyaline membrane with interstitial edema and proliferation of interstitial fibroblasts suggesting the presence of both acute exudative and late organizing phases.

Treatment of AIP is usually supportive and initially consists of oxygen supplement and noninvasive mechanical ventilation, but mechanical ventilation with positive-end-expiratory pressure is required in most patients. Patients are often treated with corticosteroids, which may improve the outcome as in patients with adult respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS) (1). Treatment with newer agents such as surfactant, anti-cytokine antibodies, and inhaled nitric oxide traditionally used for ARDS, might be beneficial but are largely untested (3). However, we did not use any newer agents other than corticosteroids in this case. Even though corticosteroid was not effective in two patients who died of AIP, it was effective in their asymptomatic older sister who had an incidental finding of ground-glass opacities on chest CT. Her chest CT and PFT findings were improved after administration of oral steroid agent.

Despite occurring in previously healthy persons, AIP is associated with a poor prognosis (5). According to a review of patient characteristics in the published series of AIP by Bouros et al. in 2000, the mean 6-month mortality of patients with AIP was 78% (range, 60-100%) (1). Olson et al. reported a 41% survival rate from 29 patients (1), two other small published series, total 2 of 13 patients survived (3, 9).

The prevalence of AIP in childhood is rare, and only two cases of AIP have been previously reported; one of them survived after intravenous antibiotics and corticosteroid treatment (8), and the other died on 40th day of admission (3). In this case, the patient showed the same clinical course and radiologic, histologic findings as the previously reported AIP cases in adults. Notably, two other siblings, her 2-yr-old brother and 8-yr-old sister, also showed the similar radiologic findings indicative of AIP, even though they had some different degrees of symptoms and destruction of lung parenchyma.

Considering the coincidence in three children, we speculated that any genetic deficit or infectious attack might have been involved. However, we did not perform any genetic studies such as surfactant protein B and C. On the other hand, we could not exclude the possibility of an infectious origin, although the studies for infection were all negative.

In summary, this rare case of AIP in children gave us a chance to review the clinical course, radiologic and pathologic findings of AIP in children, which showed no significant difference from those of adult cases in the literature (1, 2, 7, 10). Furthermore, we first experienced three different phases of AIP in one family: one clinically, radiologically, and histoloically confirmed AIP; another clinically and radiologically highly suspected as having AIP; and the other only radioloically suspected as having AIP.

Figures and Tables

References

1. Bouros D, Nicholson AC, Polychronopoulos V, du Bois RM. Acute interstitial pneumonia. Eur Respir J. 2000. 15:412–418.

2. Wittram C, Mark EJ, McLoud TC. CT-histologic correlation of the ATS/ERS 2002 classification of idiopathic interstitial pneumonias. Radiographics. 2003. 23:1057–1071.

3. Katzenstein AL, Myers JL, Mazur MT. Acute interstitial pneumonia. A clinicopathologic, ultrastructural, and cell kinetic study. Am J Surg Pathol. 1986. 10:256–267.

4. Vourlekis JS, Brown KK, Cool CD, Young DA, Cherniack RM, King TE, Schwarz MI. Acute interstitial pneumonitis. Case series and review of the literature. Medicine (Baltimore). 2000. 79:369–378.

5. Primack SL, Hartman TE, Ikezoe J, Akira M, Sakatani M, Muller NL. Acute interstitial pneumonia: radiographic and CT findings in nine patients. Radiology. 1993. 188:817–820.

6. Ichikado K, Johkoh T, Ikezoe J, Takeuchi N, Kohno N, Arisawa J, Nakamura H, Nagareda T, Itoh H, Ando M. Acute interstitial pneumonia: high-resolution CT findings correlated with pathology. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 1997. 168:333–338.

7. American Thoracic Society. European Respiratory Society. American Thoracic Society/European Respiratory Society International Multidisciplinary Consensus Classification of the Idiopathic Interstitial Pneumonias. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2002. 165:277–304.

8. Olson J, Colby TV, Elliott CG. Hamman-Rich syndrome revisited. Mayo Clin Proc. 1990. 65:1538–1548.

PDF

PDF ePub

ePub Citation

Citation Print

Print

XML Download

XML Download