Abstract

The objective of the current study was to investigate the treatment outcomes for the use of cyclophosphamide, adriamycin, vincristine, and prednisolone (CHOP) chemotherapy in adult patients with hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis (HLH). Seventeen HLH patients older than 18 yr of age were treated with CHOP chemotherapy. A response evaluation was conducted for every two cycles of chemotherapy. With CHOP chemotherapy, complete response was achieved for 7/17 patients (41.2%), a partial response for 3/17 patients (17.6%), and the overall response rate was 58.8%. The median response duration (RD) was not reached and the 2-yr RD rate was 68.6%, with a median follow-up of 100 weeks. Median overall survival (OS) was 18 weeks (95% CI, 6-30 weeks) and the 2-yr OS rate was 43.9%. Reported grade 3 or 4 non-hematological toxicities were increased serum liver enzyme levels and stomatitis. Grade 3 or 4 hematological toxicities were leukopenia (50.8%), anemia (20%), and thrombocytopenia (33.9%). Neutropenic fever was observed in 21.6% of patients (14/65 cycles), and most of the cases were resolved with supportive care including treatment with broad-spectrum antibiotics. CHOP chemotherapy seems to be effective in adult HLH patients and the toxicities are manageable.

Hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis (HLH) is an unusual disorder characterized by persistent unexplained fever, hepatic dysfunction, massive hepatosplenomegaly, pancytopenia, hypertriglyceridemia, hypofibrinogenemia, and hemophagocytosis in the bone marrow, liver, spleen, or lymph nodes (1-3). HLH frequently occurs in children less than 2 yr of age as a familial autosomal recessive disorder (4). It has also been associated with infectious or malignant diseases in a secondary form of the disorder.

The familial form of HLH progresses rapidly and is uniformly fatal without treatment, but some successes have been reported for secondary HLH patients that are Epstein-Barr virus (EBV) positive. Dexamethasone, etoposide, and cyclosporin A (CsA)-based protocols with additional intrathecal methotrexate instillation have been used for the treatment to improve survival (5). For secondary HLH, because of its feature of cytokine flooding and the resultant hemophagocytosis and its EBV association, steroid, intravenous immunoglobulin (IVIG), and CsA have been added to the cytotoxic agents used for treatment. Although diverse therapeutic regimens including cytotoxic therapy and immunomodulators have been tried, no standard treatment regimen is as yet established.

The cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin, vincristine, and prednisone (CHOP) regimen has been shown to be the most effective regimen for the treatment of malignant lymphomas in which monoclonal proliferation of lymphocytes prevails. As some core features of pathogenesis are common in HLH and malignant lymphomas, the CHOP regimen is worthy to be tested. Here we have investigated the efficacy and toxicity of the CHOP regimen for the treatment of HLH.

From March 1999 through December 2004, 46 patients older than 18 yr of age were diagnosed with HLH at four medical institutions in South Korea. Among these cases, 17 patients were treated with CHOP chemotherapy. A diagnosis of HLH was made according to the revised diagnostic criteria of the HLH study group of the Histiocyte Society (Table 1) (1). Informed consent was obtained from each patient.

The possible association of HLH with EBV was analyzed by the use of serological assays. Serological tests were performed with IgG and IgM antibodies against the EBV viral capsid antigen (VCA), early antigen (EA), and EBV nuclear antigen (EBNA) using the enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) method. An active EBV infection was suggested when patients with a positive anti-EBNA antibody exhibited one of the following conditions: 1) anti-VCA IgG antibody titer over 1:640, 2) paired anti-VCA IgG titer rising fourfold, or 3) anti-EA IgG titer greater than 1:40 (2).

A cytomegalovirus (CMV) antigenemia test and serological analyses for viruses, including human herpesvirus-6, human simplex virus type 1/2, varicella zoster virus, parvovirus B19, and CMV in the serum were also performed.

Seventeen patients were initially treated with CHOP (750 mg/m2 cyclophosphamide intravenously on day 1; 50 mg/m2 doxorubicin intravenously on day 1; 1.4 mg/m2 vincristine, maximal dose of 2 mg, on day 1; and 40 mg/m2 prednisone for five days) chemotherapy. Reductions by 25% in the dose of cyclophosphamide and doxorubicin were made for all succeeding courses of CHOP if grade 4 hematological toxicities or grade 3/4 non-hematological toxicities were observed in the prior course of chemotherapy. Chemotherapy was repeated every 3 to 4 weeks for a total of six to eight cycles in responding patients. If the neutrophil count was lower than 1,500/µL or the platelet count was lower than 100,000/µL, the cycle was delayed for up to two weeks, or treatment was terminated when chemotherapy was delayed for more than two weeks. The patients that had an human leukocyte antigen (HLA)-matched sibling donor underwent stem cell transplantation (SCT) at any treatment schedule. However, some patients that had an HLA-matched sibling donor did not undergo SCT due to early death or refusal to undergo SCT.

Complete response (CR) was considered if there was unequivocal resolution of clinical signs and symptoms, as well as normalization of the laboratory findings, particularly the serum level of ferritin. Partial response (PR) was defined as a persistent fever and other symptoms of HLH or an abnormally high level of serum ferritin in the absence of definitive symptoms. All other cases were defined as no response (NR). The evaluation of response was performed after every two cycles of CHOP chemotherapy.

The response duration (RD) was calculated from the time of the first documented response to the time of disease progression or death. The overall survival (OS) was calculated from the beginning of treatment to the time of analysis or death, and calculated using the Kaplan-Meier method. Statistical significance was determined at a level of p<0.05. The software package SPSS for Windows (version 13.0, SPSS. Chicago, IL, U.S.A.) was used for the statistical analysis.

The patient characteristics, including the initial clinical and laboratory data, are detailed in Table 2. The age of the patients ranged from 18 to 77 yr, with a median age of 38 yr, and nine patients were male and eight patients were female. Seven patients had a malignant lymphoma (three with a diffuse large B cell lymphoma, two with a peripheral T cell lymphoma, and two with an extranodal NK/T cell lymphoma). Five patients were associated with EBV infection. No etiology was found in the remaining five patients. Bone marrow involvement of the lymphoma cells was detected in four patients among the seven patients with malignant lymphoma.

While the most common presenting symptom was fever (17 cases, 100%), hepatosplenomegaly, lymphadenopathy, increased level of serum lactate dehydrogenase (range, 635-4,541 IU/L; normal range, 180-460 IU/L), and increased serum ferritin level (range, 500-5114 ng/mL; normal range, 15-332 ng/mL) were the fundamental findings for the HLH patients. Thrombocytopenia (14 cases, 82.4%) was a common finding at the initial diagnosis compared to anemia (6 cases, 35.3%) and leukopenia (4 cases, 23.5%). Jaundice, elevated levels of serum liver enzymes, coagulopathy with a prolonged prothrombin time and/or an activated partial thromboplastin time and hypertriglyceridemia were also noted in more than half of the patients. In all cases, bone marrow aspiration and a biopsy revealed varying degrees of histiocyte proliferation with active hemophagocytosis.

In the current study, a total of 65 courses of chemotherapy were administered, with a median of three courses (range, 1-8) given per patient. Six patients received one or two courses, four patients received three courses, six patients received six courses, and only one patient received eight courses of chemotherapy. One (case 8) out of seven patients that achieved CR received only two courses of chemotherapy because the patient was offered treatment with high-dose chemotherapy followed by stem cell transplantation.

Based on intent-to-treat analysis, the overall response rate was 58.8% (10 patients: 5 patients with a malignant lymphoma, three patients with EBV, and two patients with an unknown etiology). Seven patients (41.2%) achieved CR and three patients (17.6%) achieved PR. Six of seven patients who achieved CR are currently alive. Five of seven patients (71.4%) with a malignant lymphoma, three of five patients (60%) with EBV, and two of five patients (40%) with an unknown etiology had a response (Table 3). The median follow-up duration was 100 weeks (range 16-272 weeks); the median RD was not reached, and the 2-yr RD rate was 68.6%. The median OS was 18 weeks (95% CI, 6-30 weeks) and the 2-yr OS rate was 43.9% (Fig. 1).

Nine patients died within 18 weeks. Among these early deaths, three patients achieved PR and six achieved NR with CHOP chemotherapy. The underlying disease was a malignant lymphoma for case 3 and an unknown etiology for cases 14 and 16 (Table 4), and all of these patients received salvage chemotherapy (dexamethasone, high-dose cytarabine and cisplatin [DHAP]) or (etoposide, methylprednisolone, high-dose cytarabine and cisplatin [ESHAP]), but all of the patients died within 16 weeks due to disease progression. Cases 4 and 8 that had an underlying disease of malignant lymphoma and EBV underwent allogeneic SCT; however, all of the patients died from infection (Table 4).

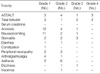

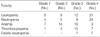

All 17 patients were assessable for toxicities associated with CHOP chemotherapy. Dose reductions were required for six patients (35.3%; a result of grade 4 hematological toxicity in five patients and a grade 4 hepatotoxicity in one patient). Ten chemotherapy cycles (15.4%) were delayed due to a hematological toxicity or patient noncompliance. A few patients required a dose reduction of full-dose CHOP, such that 95.7% of the intended dose was delivered throughout the chemotherapies.

Non-hematological toxicities were predominantly grade 1 or 2. The most frequent non-hematological toxicity was hepatotoxicity. Gastrointestinal toxicities were also common, particularly anorexia, nausea/vomiting and stomatitis, which were well controlled with supportive care. Transient diarrhea and constipation were also reported. No renal toxicity was observed (Table 5).

The hematological toxicities are shown in Table 6. Grade 3 or 4 leukopenia occurred after 33 courses (51.8%) and grade 3 or 4 neutropenia after 31 courses (50.7%) of chemotherapy. Grade 3 or 4 anemia and thrombocytopenia were observed after 13 (20%) and 22 (33.9%) courses of chemotherapy, respectively. There were grade 3 or 4 neutropenic fevers after 14 courses of chemotherapy (21.6%). Case 6 and 10 showed a splenic hemorrhage and pulmonary alveolar hemorrhage after the first cycle of chemotherapy, respectively; however, these patients improved with supportive management and could complete six cycles of chemotherapy safely.

While a baseline check-up of serum LDH, ferritin, triglyceride and fibrinogen levels were performed, only the serum LDH level could be checked serially with each cycle of chemotherapy. Fig. 2 shows the serial serum LDH level in patients who achieved CR compared with PR or NR. The serum LDH level decreased earlier (only after the first cycle of chemotherapy) in patients with CR. On the other hand, serum LDH sustained a high level in spite of continuous chemotherapy in patients with PR or NR.

Although etoposide-containing immunochemotherapy has become a recommended treatment for childhood EBV-HLH (3), treatment results for adult cases have seldom been reported. In addition, treatment strategies for lymphoma-associated HLH (LAHLH) have not yet been established.

Miyahara et al. previously reported the use of standard cytotoxic regimens (CHOP±L-asparaginase or etoposide) on 7 patients with peripheral B-cell LAHLH (2) and the reported outcome was poor (only one patient achieved CR and had disease-free survival). In this study, most patients were elderly (the median age was 67 yr with a range of 48-75 yr). Considering that a patient age older than 30 yr is an adverse risk factor (6), this study reminds us of the importance of age. In the current study, the overall response rate was 58.8%; seven of 17 patients with HLH achieved CR and most of the patients (six patients) are still alive. Thus, it is conceivable that the better treatment outcomes of the current study, as compared with the outcomes reported by Miyahara et al., are due to the relatively younger aged population of the patients in the current study (median age 38 yr).

EBV-HLH often mimics a T-cell lymphoma biologically (7). EBV-HLH should be considered as a malignant entity and should be treated with intensive cytotoxic chemotherapy or stem cell transplantation (7-12). As deaths resulting from EBV-HLH are largely caused by the cytokine storm that results in multiple organ failure (7), to avoid this risk, early introduction of treatment is important to achieve a good result in patients with EBV-HLH. The treatment objective is to control the cytokine storm induced by virus infection and to eradicate the proliferating virus-infected cells. Thus far, this can be solely achieved by treatment with cytotoxic agents such as etoposide (7). Imashuku et al. reported that 43 of 47 patients had a response (34 CR and 9 PR) and a 4-yr OS rate of 78.3±6.7% when introducing an etoposide-containing regimen to pediatric patients with EBV-HLH (13), suggesting etoposide has a potential of survival time prolongation. However, results for adult patients with EBV-HLH who were treated with an etoposide-based regimen have been seldom reported. Recently, Imashuku et al. reported that seven young adults patients with EBV-HLH receiving etoposide early after diagnosis showed a 2.5-yr survival of 85.7% (14). These investigators concluded that early installation of etoposide is an effective way to treat EBV-HLH in young adults as well as in children. However, this study included a small number of young adult patients with EBV-HLH, and was not conclusive for adult patients. A successful treatment with CPT-11 and adriamycin for HLH associated with intravascular lymphomatosis has also been reported to extend the drug choice (15). Considering that CHOP regimen is a standard chemotherapy regimen for aggressive non-Hodgkin's lymphoma, CHOP can be considered as an effective tool to treat HLH combined with malignant lymphoma. For EBV-HLH, immunossupressive agents (cyclophosphamide, vincristine, and prednisolone) can decrease hypercytokinemia, which causes early mortality, and a cytotoxic agent such as adriamycin can kill the EBV-infected hemophagocytic cells. In this study, 3 of the 5 patients with EBV-HLH that were treated with CHOP chemotherapy showed a CR, and at least 2 patients were still alive at the time of analysis. Therefore, although based on a small number of patients in the current study, CHOP chemotherapy shows a therapeutic potential in adult patients with EBV-HLH.

The lack of solid data on standard treatment protocols for adult patients with HLH is, in part, due to the rare incidence of the disease. As the difference in the therapeutic efficacy between CHOP and the etoposide-based regimen is not yet clear, more multi-center trials are needed to determine a more appropriate regimen to use in adult patients with HLH.

In the current study, the serum LDH level was checked serially after each cycle of CHOP chemotherapy and showed very early normalization in patients who achieved CR compared with patients who achieved PR or NR. Based on this result, it may be postulated that serum LDH levels could be used as a surrogate marker to determine whether to proceed or not with CHOP chemotherapy.

In conclusion, CHOP chemotherapy showed a relatively favorable activity for adult patients with HLH and the toxicities were manageable. Because of the small sample size in this current study, further studies that include a large number of patients are needed.

Figures and Tables

Fig. 1

Two-year response duration rate 68.6% (A) and overall survival rate 43.9% (B) for adult patients with hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis.

Fig. 2

Serial serum LDH level. (A) HLH patients who showed CR after CHOP chemotherapy. (B) HLH patients who showed PR or NR after CHOP chemotherapy.

Table 4

Treatment outcomes

Death d/t Ds progression.

CTx, chemotherapy; wk, week; Tx, treatment; OS, overall survival; CR, complete response; PR, partial response; NR, no response; DHAP, dexamethasone, cytarabine and cisplatin; NE, not evaluable; AlloSCT, allogeneic stem cell transplantation; d/t, due to; Ds, disease; F/U, follow-up; EBV, Epstein-Barr virus; ESHAP, etoposide, methylprednisolone, high-dose cytarabine and cisplatin.

References

1. Janka GE, Schneider EM. Modern management of children with haemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis. Br J Haematol. 2004. 124:4–14.

2. Miyahara M, Sano M, Shibata K, Matsuzaki M, Ibaraki K, Shimamoto Y, Tokunaga O. B-cell lymphoma-associated hemophagocytic syndrome: clinicopathological characteristics. Ann Hematol. 2000. 79:378–388.

3. Imashuku S, Hibi S, Ohara T, Iwai A, Sako M, Kato M, Arakawa H, Sotomatsu M, Kataoka S, Asami K, Hasegawa D, Kosaka Y, Sano K, Igarashi N, Maruhashi K, Ichimi R, Kawasaki H, Maeda N, Tanizawa A, Arai K, Abe T, Hisakawa H, Miyashita H, Henter JI. Effective control of Epstein-Barr virus-related hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis with immunochemotherapy. Histiocyte Society. Blood. 1999. 93:1869–1874.

4. Gencik A, Signer E, Muller H. Genetic analysis of familial erythrophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis. Eur J Pediatr. 1984. 142:248–252.

5. Henter JI, Arico M, Egeler RM, Elinder G, Favara BE, Filipovich AH, Gadner H, Imashuku S, Janka-Schaub G, Komp D, Ladisch S, Webb D. HLH-94: a treatment protocol for hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis. HLH study group of the Histiocyte Society. Med Pediatr Oncol. 1997. 28:342–347.

6. Kaito K, Kobayashi M, Katayama T, Otsubo H, Ogasawara Y, Sekita T, Saeki A, Sakamoto M, Nishiwaki K, Masuoka H, Shimada T, Yoshida M, Hosoya T. Prognostic factors of hemophagocytic syndrome in adults: analysis of 34 cases. Eur J Haematol. 1997. 59:247–253.

7. Imashuku S. Clinical features and treatment strategies of Epstein-Barr virus-associated hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis. Crit Rev Oncol Hematol. 2002. 44:259–272.

8. Su IJ, Wang CH, Cheng AL, Chen RL. Hemophagocytic syndrome in Epstein-Barr virus-associated T-lymphoproliferative disorders: disease spectrum, pathogenesis, and management. Leuk Lymphoma. 1995. 19:401–406.

9. Dolezal MV, Kamel OW, van de Rijn M, Cleary ML, Sibley RK, Warnke RA. Virus-associated hemophagocytic syndrome characterized by clonal Epstein-Barr virus genome. Am J Clin Pathol. 1995. 103:189–194.

10. Chen JS, Tzeng CC, Tsao CJ, Su WC, Chen TY, Jung YC, Su IJ. Clonal karyotype abnormalities in EBV-associated hemophagocytic syndrome. Haematologica. 1997. 82:572–576.

11. Ito E, Kitazawa J, Arai K, Otomo H, Endo Y, Imashuku S, Yokoyama M. Fatal Epstein-Barr virus-associated hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis with clonal karyotype abnormality. Int J Hematol. 2000. 71:263–265.

12. Yagita M, Iwakura H, Kishimoto T, Okamura T, Kunitomi A, Tabata R, Konaka Y, Kawa K. Successful allogeneic stem cell transplantation from an unrelated donor for aggressive Epstein-Barr virus-associated clonal T-cell proliferation with hemophagocytosis. Int J Hematol. 2001. 74:451–454.

13. Imashuku S, Kuriyama K, Teramura T, Ishii E, Kinugawa N, Kato M, Sako M, Hibi S. Requirement for etoposide in the treatment of Epstein-Barr virus-associated hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis. J Clin Oncol. 2001. 19:2665–2673.

14. Imashuku S, Kuriyama K, Sakai R, Nakao Y, Masuda S, Yasuda N, Kawano F, Yakushijin K, Miyagawa A, Nakao T, Teramura T, Tabata Y, Morimoto A, Hibi S. Treatment of Epstein-Barr virus-associated hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis (EBV-HLH) in young adults: a report from the HLH study center. Med Pediatr Oncol. 2003. 41:103–109.

15. Ise M, Sakai C, Tsujimura H, Kumagai K, Takenouchi T, Takagi T. Successful treatment with CPT-11 and adriamycin for hemophagocytic syndrome associated with intravascular lymphomatosis. Rinsho Ketsueki. 1998. 39:1131–1136.

PDF

PDF ePub

ePub Citation

Citation Print

Print

XML Download

XML Download