Abstract

Although acquired mutations in the GATA1 gene have been reported for Down syndrome-related acute megakaryoblastic leukemia (DS-AMKL) in Caucasians, this is the first report of a Korean Down syndrome patient with AMKL carrying a novel mutation of the GATA1 gene. A 3-yr-old Korean girl with Down syndrome was admitted to our hospital complaining of pallor and fever. The findings of a peripheral blood smear and bone marrow study were compatible with the presence of AMKL. A chromosome study showed 48,XX,-7,+21c,+21,+r[3]/47,XX,+21c[17]. Following GATA1 gene mutation analysis, a novel mutation, c.145dupG (p.Ala49GlyfsX18), was identified in the N-terminal activation domain of the GATA1 gene. This mutation caused a premature termination at codon 67 and expression of an abnormal GATA-1 protein with a defective N-terminal activation domain, and the absence of full-length GATA-1 protein. This case demonstrates that a leukemogenic mechanism for DS-AMKL is contributed by a unique collaboration between overexpressed genes from trisomy 21 and an acquired GATA1 mutation previously seen in Caucasians and now in a Korean patient.

Children with Down syndrome are predisposed to developing acute leukemia. The most common leukemia associated with Down syndrome is acute megakaryoblastic leukemia (AMKL), and the incidence is approximately 500-fold higher than in healthy children (1). Transient myeloproliferative disorder (TMD) is a leukemoid reaction occurring occasionally in Down syndrome newborn infants, and is characterized by the rapid growth of abnormal blast cells expressing megakaryocytic markers. Although most TMD cases resolve spontaneously, AMKL develops in approximately 20% to 30% of TMD cases in the first 4 yr of life, often preceded by a myelodysplastic phase. Recently, acquired mutations in the N-terminal activation domain of the GATA1 gene, encoding a zinc-finger transcription factor that regulates the normal development of the megakaryocytic, erythroid, basophilic/mast cell and eosinophilic lineages, have been reported in TMD and Down syndrome-related AMKL (DS-AMKL) (2). Two isoforms of GATA-1 protein are usually detected: a full-length GATA-1 translated from the first start codon ATG on exon 2, and a 40-kDa shorter form, GATA-1s that initiated from an ATG on exon 3. Most of the mutations in TMD and DS-AMKL were located in the regions including exon 2 and an identical mutation in specimens from TDM and AMKL have been found in Down syndrome patients (3-8). The mutation results in the introduction of a premature stop codon in the gene sequence that encodes the N-terminal activation domain, and a lack of expression of the full-length GATA-1.

Here we describe a 3-yr-old girl patient with DS-AMKL, who was found to have a novel GATA1 gene mutation and complex cytogenetic aberrations including constitutional trisomy 21, clonal monosomy 7, and an additional copy of chromosome 21. To the best of our knowledge, this is a first case of DS-AMKL with a GATA1 gene mutation described in Korea. This case indicate that expression of an abnormal GATA-1s with a defective N-terminal activation domain, in the absence of full-length GATA-1, and that other genetic changes contribute to the development of DS-AMKL, previously described in Caucasians and now in a Korean patient.

A 3-yr-girl patient with Down syndrome was admitted because of pallor and fever. Initial laboratory tests showed Hb 2.7 g/dL, WBC 9.77×109/L, and platelets 7×109/L. A peripheral blood smear revealed that 52% of the white blood cells were blasts with a round nucleus with fine reticular chromatin, one to three nucleoli and cytoplasmic bleb, and the bone marrow aspirate smear revealed that the blasts were counted at 73% (Fig. 1A). Flow cytometric analyses showed that these blasts were CD13+, CD33+, CD34+, HLA-DR+, CD61+, and aberrant CD7+. A cytochemical stain showed reactivity with CD61 and punctuate nonspecific esterase reactivity and negativity for sudan black B and peroxidase; the blasts were compatible with the features of megakaryoblasts (Fig. 1B). Cytogenetic analysis of the bone marrow cells revealed 48,XX,-7,+21c,+21,+r[3]/47,XX, +21c[17] (Fig. 2A). We analyzed the GATA1 mutation in this patient after obtaining informed consent from the parents. The genomic DNA was isolated from the bone marrow leukocytes using a Wizard genomic DNA purification kit following the manufacturer's instruction (Promega, Madison, WI, U.S.A.). The GATA1 gene was amplified by use of the polymerase chain reaction (PCR) with use of the appropriate primers (available upon request) and a thermal cycler (Model 9700, Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA, U.S.A.). Direct DNA sequencing was performed with the BigDye Terminator Cycle Sequencing Ready Reaction kit (Applied Biosystems) on an ABI Prism 3100 genetic analyzer (Applied Biosystems). Following GATA1 gene mutation analysis, a novel mutation, c.145dupG (p.Ala49GlyfsX18), was identified in the N-terminal activation domain, exon 2 of GATA1 (Fig. 3). This mutation resulted in a premature stop codon at amino acid 67 and resulted in the production of GATA-1s. The parents of the patient denied a history of TMD. A final diagnosis was confirmed as DS-AMKL. The patient received intensified induction chemotherapy (daunorubicin 45 mg/m2 with cardioxane, cytosine arabinoside 100 mg/m2, and intrathecal cytosine arabinoside 30 mg) and achieved complete remission on day 28. The follow-up studies on day 28 revealed cytogenetic and morphological remission. The leukemia relapsed under the course of the consolidation chemotherapy, 11 months later. The blasts reappeared on a peripheral blood smear and bone marrow aspirate smear, and represented up to 34% of the white blood cells and 49% of all of the nucleated cells, respectively. Flow cytometric analyses showed the same results as the initial leukemic clone. Cytogenetic analysis with bone marrow cells revealed only constitutional trisomy 21 (47,XX,+21c[20]) (Fig. 2B). Although the peak of the mutated GATA1 gene sequence of the specimen taken after relapse was lower than that of the initial specimen, the same mutation was detected after relapse.

Recently, acquired mutations in the GATA1 gene that have been reported in nearly all cases of TMD and DS-AMKL have been shown to be specific for DS-AMKL (3, 7). GATA1 mutations are present in blasts of TMD and show the identical GATA1 mutation in sequential samples collected from a patient during TMD, and subsequently AMKL. These findings suggest a model of malignant transformation in DS-AMKL in which GATA1 mutations are an early event and AMKL arises from latent TMD clones following initial apparent remission (9). The mutation expresses only a truncated mutant of the GATA1 gene and a short form of the protein, GATA-1s, is produced. Full-length GATA-1 induces differentiation toward the erythroid/megakaryoblastic lineage. However, expression of GATA-1s did not induce erythroid/megakaryoblastic differentiation. These results indicate that expression of only GATA-1s with a defective N-terminal activation domain contributes to the expansion of TMD blast cells, and that other genetic changes contribute to the development of AMKL in Down syndrome (7, 9).

Down syndrome of this patient was recognized by the physician at admission. This patient had no known clinical history of TMD. The GATA1 mutation may be present at birth in many cases in patients without known clinical TMD, and who later develop AMKL (6). Unfortunately, we did not confirm the presence of the same GATA1 mutation at birth in this case. After relapse, the same GATA1 mutation was detected.

Studies on TMD or AMKL in Down syndrome are especially lacking for Korean patients.

The detection of GATA1 mutation is highly suggestive of DS-AMKL, and is important in the understanding Down syndrome-related leukemogenesis, and a new target for the detection of minimal residual disease (10). For children with no obvious symptoms of Down syndrome, detection of a GATA1 mutation is highly informative to distinguish between DS-AMKL and a non-Down syndrome AMKL. However, GATA1 mutations are not associated with every case of DS-AMKL. This may be due to a technical limitation in detecting a GATA1 mutation in a sample with a low blast population, or alternatively, an indication that a separate class of DS-AMKL exists. While GATA1 mutations have been detected in children diagnosed with DS-AMKL as old as 50 months, very few cases of children older than 4 yr have been studied to be significant (8). Children older than 4 yr and with the absence of a GATA1 mutation in DS-AMKL face the worst prognosis. Further studies into the potential use of GATA1 mutation analysis for the diagnosis of DS-AMKL are therefore needed.

GATA1 mutations have been found in otherwise healthy Down syndrome neonates at birth, that have not yet developed TMD or AMKL (6). These findings suggest that acquired mutations in GATA1 and the generation of GATA-1s cooperate frequently with trisomy 21 in initiating megakaryoblastic proliferation, but are insufficient for the progression to AMKL. Mutagenesis of GATA1 is an initiating event in Down syndrome-associated leukemogenesis. GATA1 mutations have not been found in non-Down syndrome patients with leukemia of any kind, with the following exception. Children without Down syndrome, but with acquired trisomy 21, trisomy 21 mosaicism, or tertasomy 21 in their leukemic cells, may, on rare occasions, present with AMKL that harbors a GATA1 mutation (11). Therefore, increased expression of certain chromosome 21 genes in the same cell that carries the GATA1 mutation may enhance its proliferation and survival (12). There are several genes on the small chromosome 21 that encode proteins that may enhance megakaryopoiesis. These genes include RUNX1/AML1 (13, 14), ERG (15), Ets2, and a newly discovered group of genes coding for regulatory micro-RNAs (12, 16). ERG is an Ets transcription factor and excess expression of ERG in hematopoietic progenitor cells, coupled with a differentiation arrest is caused by the acquisition of mutations in GATA1 (15). Overexpression of ERG, perhaps in conjunction with other factors such as Ets2, may contribute to expanded megakaryopoiesis cells harboring trisomy 21. RUNX1/AML1 is known to be the most frequent target for a chromosomal translocation in leukemia. Recently, point mutations in the Runt domain of the AML1 gene have also been reported in cells from leukemia patients (17). Interestingly, AML1 mutations are frequently found in myeloid malignancies with acquired 21 trisomy (18). It has been suggested that increased RUNX1 activity has a role in DS-AMKL development due to the physical interaction and synergy between GATA1 and RUNX1 (13). To understand further the mechanisms of a lineage-specific malignant conversion, it is very important to identify the gene or genes on chromosome 21 that cooperate with mutated GATA1 as well as additional genetic changes in TMD blast cells during the development of DS-AMKL. Therefore, the development of DS-AMKL requires at least three cooperating events-trisomy 21, a GATA1 mutation, and a third, as yet undefined, additional genetic alteration (16).

Although acquired mutations in the GATA1 gene have been reported in DS-AMKL in Caucasians, this is a first case of a Korean Down syndrome patient with AMKL carrying a novel mutation of GATA1 gene. This case demonstrates that expression of the abnormal GATA-1s with a defective N-terminal activation domain, in the absence of full-length GATA-1, contributes to the development of DS-AMKL, as seen previously in Caucasians and now in a Korean patient. Large and prospective studies are needed to reveal GATA1 mutations and additional genetic alternations, such as overexpression of RUNX1/AML1 or EGR, for the development of DS-AMKL in Down syndrome patients.

Figures and Tables

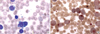

Fig. 1

Bone marrow aspiration revealed that blasts were 73% (A) and cytochemical stain showed reactivity with CD61 and punctuate nonspecific esterase reactivity (B), and negativity on peroxidase and sudan black B.

Fig. 2

Cytogenetic analysis of bone marrow cells revealed 48,XX,7,+21c,+21,+r[3]/47,XX,+21c[17] at initial diagnosis (A) and only constitutional trisomy 21 at relapse (B).

Fig. 3

Direct DNA sequencing analyses of the GATA1 gene revealed a novel mutation, c.145dupG (p.Ala49GlyfsX18), identified in the N-terminal activation domain of exon 2 of GATA1. This mutation produced a premature stop codon at amino acid 67 and expression of an abnormal short variant, GATA-1s, with a defective N-terminal activation domain, in the absence of the full-length GATA-1. The same mutation was discovered in a specimen taken following relapse.

References

1. Zipursky A, Poon A, Doyle J. Leukemia in Down syndrome: a review. Pediatr Hematol Oncol. 1992. 9:139–149.

2. Wechsler J, Greene M, McDevitt MA, Anastasi J, Karp JE, Le Beau MM, Crispino JD. Acquired mutations in GATA1 in the megakaryoblastic leukemia of Down syndrome. Nat Genet. 2002. 32:148–152.

3. Magalhaes IQ, Splendore A, Emerenciano M, Figueiredo A, Ferrari I, Pombo-de-Oliveira MS. GATA1 mutations in acute leukemia in children with Down syndrome. Cancer Genet Cytogenet. 2006. 166:112–116.

4. Crispino JD. GATA1 mutations in Down syndrome: implications for biology and diagnosis of children with transient myeloproliferative disorder and acute megakaryoblastic leukemia. Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2005. 44:40–44.

5. Magalhaes IQ, Splendore A, Emerenciano M, Cordoba MS, Cordoba JC, Allemand PA, Ferrari I, Pombo-de-Oliveira MS. Transient neonatal myeloproliferative disorder without Down syndrome and detection of GATA1 mutation. J Pediatr Hematol Oncol. 2005. 27:50–52.

6. Ahmed M, Sternberg A, Hall G, Thomas A, Smith O, O'Marcaigh A, Wynn R, Stevens R, Addison M, King D, Stewart B, Gibson B, Roberts I, Vyas P. Natural history of GATA1 mutations in Down syndrome. Blood. 2004. 103:2480–2489.

7. Greene ME, Mundschau G, Wechsler J, McDevitt M, Gamis A, Karp J, Gurbuxani S, Arceci R, Crispino JD. Mutations in GATA1 in both transient myeloproliferative disorder and acute megakaryoblastic leukemia of Down syndrome. Blood Cells Mol Dis. 2003. 31:351–356.

8. Rainis L, Bercovich D, Strehl S, Teigler-Schlegel A, Stark B, Trka J, Amariglio N, Biondi A, Muler I, Rechavi G, Kempski H, Haas OA, Izraeli S. Mutations in exon 2 of GATA1 are early events in megakaryocytic malignancies associated with trisomy 21. Blood. 2003. 102:981–986.

9. Hitzler JK, Cheung J, Li Y, Scherer SW, Zipursky A. GATA1 mutations in transient leukemia and acute megakaryoblastic leukemia of Down syndrome. Blood. 2003. 101:4301–4304.

10. Pine SR, Guo Q, Yin C, Jayabose S, Levendoglu-Tugal O, Ozkaynak MF, Sandoval C. GATA1 as a new target to detect minimal residual disease in both transient leukemia and megakaryoblastic leukemia of Down syndrome. Leuk Res. 2005. 29:1353–1356.

11. Sandoval C, Pine SR, Guo Q, Sastry S, Stewart J, Kronn D, Jayabose S. Tetrasomy 21 transient leukemia with a GATA1 mutation in a phenotypically normal trisomy 21 mosaic infant: case report and review of the literature. Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2005. 44:85–91.

12. Izraeli S, Rainis L, Hertzberg L, Smooha G, Birger Y. Trisomy of chromosome 21 in leukemogenesis. Blood Cells Mol Dis. 2007. 39:156–159.

13. Xu G, Kanezaki R, Toki T, Watanabe S, Takahashi Y, Terui K, Kitabayashi I, Ito E. Physical association of the patient-specific GATA1 mutants with RUNX1 in acute megakaryoblastic leukemia accompanying Down syndrome. Leukemia. 2006. 20:1002–1008.

14. Elagib KE, Racke FK, Mogass M, Khetawat R, Delehanty LL, Goldfarb AN. RUNX1 and GATA-1 coexpression and cooperation in megakaryocytic differentiation. Blood. 2003. 101:4333–4341.

15. Rainis L, Toki T, Pimanda JE, Rosenthal E, Machol K, Strehl S, Gottgens B, Ito E, Izraeli S. The proto-oncogene ERG in megakaryoblastic leukemias. Cancer Res. 2005. 65:7596–7602.

16. Vyas P, Crispino JD. Molecular insights into Down syndrome-associated leukemia. Curr Opin Pediatr. 2007. 19:9–14.

17. Osato M, Yanagida M, Shigesada K, Ito Y. Point mutations of the RUNx1/AML1 gene in sporadic and familial myeloid leukemias. Int J Hematol. 2001. 74:245–251.

18. Preudhomme C, Warot-Loze D, Roumier C, Grardel-Duflos N, Garand R, Lai JL, Dastugue N, Macintyre E, Denis C, Bauters F, Kerckaert JP, Cosson A, Fenaux P. High incidence of biallelic point mutations in the Runt domain of the AML1/PEBP2 alpha B gene in Mo acute myeloid leukemia and in myeloid malignancies with acquired trisomy 21. Blood. 2000. 96:2862–2869.

PDF

PDF ePub

ePub Citation

Citation Print

Print

XML Download

XML Download