Abstract

Although high-dose intravenous immunoglobulin (IVIG) is generally considered a safe medication for various immune-mediated diseases, thrombotic events have been reported as a complication of the therapy. We report a case who developed thrombotic complications after receiving IVIG. A 56-yr-old woman with idiopathic thrombocytopenic purpura received IVIG at a dose of 400 mg/kg/day for five days. Three days after the administration of IVIG, the patient developed painful edema in the left leg. Lower extremity doppler ultrasound revealed deep vein thrombosis in the left leg. Chest computed tomography (CT) scan demonstrated a filling defect indicating thromboembolism of the right pulmonary artery. After three weeks of enoxaparin therapy, her symptoms and pulmonary embolism on CT improved. This case suggests clinicians should be cautious in the development of thromboembolism by administration of IVIG, especially in patients with thrombophilia.

High-dose intravenous immunoglobulin (IVIG) has been used safely in various autoimmune disorders such as Kawasaki syndrome, hemolytic anemia, neuroimmunological disorders, and idiopathic thrombocytopenic purpura (ITP). The therapeutic indications for the use of IVIG have been broadened to include various diseases during the last few decades (1-3). Serious adverse reactions of IVIG are rare, including anaphylactic reactions, especially in patients with selective IgA deficiency, renal tubular necrosis and aseptic meningitis. In general, IVIG has been considered a safe medication, with manageable adverse events such as fever, chills, myalgia, and headache, occurring in no more than 10% of the patients (1, 4-7).

Since the thromboembolic complications associated with IVIG treatment was first reported by Woodruff et al. (8) in 1986, IVIG-associated thrombotic complications have been steadily reported, and the incidence has been estimated to be between 3% and 5% (1, 2). In Korea, a case of cerebral infarction following IVIG therapy in a patient with Guillain-Barre syndrome has been reported (9).

In this report, we describe a case of IVIG-induced deep vein thrombosis with pulmonary thromboembolism in an ITP patient without underlying cardiovascular risk factors.

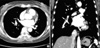

A 56-yr-old woman presented with petechiae and bruises, which had developed six months before. She had no previous medical history or family history of bleeding or thrombotic tendency. She denied use of any medication, such as oral contraceptives, herbs, aspirin, nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory agents, or antibiotics. On physical examination, she had petechiae on palate and bruise on her upper and lower extremities. Calf swelling and splenomegaly were not noticed. Her initial platelet count was 3,000/µL, hemoglobin 12.6 g/dL, and white blood cell count 7,720/µL. Antiplatelet antibody was negative. Peripheral blood smear showed markedly decreased platelet in number. Bone marrow aspirate and biopsy showed relatively hypocellular marrow for her age with normal maturation (cellularity 25%), and megakaryocytes were adequate in number with normal maturation. After the diagnosis of ITP, high-dose prednisolone (1 mg/kg) was administered for 2 months, to which the patient was refractory. For acute management of gum bleeding at platelet count 10,000/µL, she received IVIG at a dose of 400 mg/kg/day for five days with no immediate acute toxicities during infusion. Three days after the administration of IVIG, the patient developed painful edema in her left leg. She did not complain of respiratory or cardiac symptoms such as dyspnea or tachypnea. On physical examination, pitting edema of grade III was noticed in her left lower leg with weakly palpated pulse at left dorsalis pedis artery. Her hemoglobin level was 11.4 g/dL, hematocrit 36.4%, white blood cell count 2,210/µL, and platelets 14,000/µL. VDRL and FANA were all negative. Lupus anticoagulant was 35.0 sec and anticardiolipin antibodies, IgM and IgG, were negative. Antithrombin III activity, protein C and protein S activity, and homocysteine were within normal limits. An electrocardiogram showed a normal sinus rhythm at 65 beats per minute with a normal axis and intervals. Her chest radiograph was normal. Transthoracic echocardiogram showed normal left ventricular cavity size and systolic function, diastolic dysfunction of grade I, and right ventricular systolic pressure of 32 mmHg. Extremity doppler ultrasound revealed diffuse thrombosis from the left proximal femoral vein to the popliteal vein (Fig. 1). Chest CT scan revealed a filling defect in the right interlobar pulmonary artery, which was indicative of thromboembolism (Fig. 2). She was immediately treated with subcutaneous enoxaparin at a dose of 60 mg twice a day. After three weeks of enoxaparin therapy, her follow-up chest CT scan revealed a complete disappearance of embolism in the right pulmonary artery (Fig. 3). Pitting edema in the left lower leg was completely resolved, and platelet count was normalized following high-dose steroid therapy. Because her platelet count was persistently decreased despite high-dose steroid therapy, she underwent splenectomy. After splenectomy, her platelet count was stabilized with a range of 45,000-50,000/µL while on prednisolone and danazol and has achieved complete remission. She is currently on warfarin for deep vein thrombosis.

ITP is one of the immunologic thrombocytopenic purpura characterized by the development of autoantibodies reacting on platelet glycoproteins, which are then destroyed by phagocytosis primarily in spleen.

In the treatment of ITP, IVIG is used for patients with active bleeding or for whom major surgery is necessary (10, 11). High-dose IVIG was first used for treatment of childhood ITP by Imbach et al. (12) in 1981. The six indications approved for the IVIG product in Canadian Consensus guideline (1999) (13) include immune deficiency, idiopathic thrombocytopenic purpura, hypogammaglobulinemia, pediatric Human Immunodeficiency Virus (HIV) infection, bone marrow transplantation, and B cell chronic lymphocytic leukemia. However, the clinical use of IVIG is far from being restricted to the approved indications and off-label uses such as chronic inflammatory demyelinating polyneuropathy and Guillain-Barre syndrome are common (13, 14). In general, IVIG has been considered a safe medication, with minor adverse reactions such as fatigue, fever, headache, nausea, and myalgias, occurring in no more than 10% of patients (1, 4-7). With the wider use of IVIG, the reported rate of side effects has increased, some of them being potentially fatal (1, 8). The first report of thromboembolic events associated with IVIG therapy by Woodruff et al. (8). described four older patients with ITP who developed myocardial infarction and cerebrovascular accident after IVIG therapy, resulting in death in three of them. Paran et al. (14) described that 65 cases of IVIG-associated thrombosis had been reported in 33 articles published from 1966 to 2004 and 34 of these cases were reported in 2003. In the report, 51 cases had arterial thrombosis, including stroke, myocardial infarction, and limb ischemia. Thirteen cases had venous thrombosis, including deep vein thrombosis or pulmonary embolism, central retinal vein thrombosis, and sinus vein thrombosis. Two of the reported patients had both an arterial and a venous thrombotic event (14). Thromboembolic complications occurred within two weeks after IVIG therapy had begun, and the 63% of them occurred within 24 hr of the infusion (1, 2, 8, 14-16).

Although the pathogenesis of thrombosis secondary to IVIG is not completely understood, several mechanisms have been proposed. One plausible mechanism for IVIG-related thrombosis is the increase in blood viscosity by IVIG. High-dose IVIG increases blood viscosity from normal (1.2-1.7 cp) by 0.5 to 0.7 cp, thus causing a hypercoagulable state (2, 4, 9, 16). Previous studies reported that serum viscosity increased up to 2.9 cp immediately, following infusion of IVIG and declined gradually over the next month (14, 17). In particular, IgG has been postulated to increase viscosity through molecular interactions between proteins (2, 16, 17). The viscous effect of IVIG is dose-dependent and increases the susceptibility to thromboembolism in predisposed patients such as elderly patients and those with cardiovascular or cerebrovascular disease and atherosclerosis (1, 5, 16). If such patients are planned to receive IVIG, pretreatment screening with lower extremity ultrasound for subclinical clots, very slow infusion rate (not exceeding 200 mL/hr or 0.08 mL/kg/min) and monitoring of serum viscosity are recommended (1, 4). In addition, IVIG induces platelet activation, increased fibrinogen levels and activation of the serum complement, which may further predispose patients to thrombosis and ischemia. Some IVIG preparations have increased concentrations of factor XI, which may potentially trigger intrinsic coagulation pathway activation and thrombin formation (5, 16). Besides, IVIG may induce localized production of vasoconstrictive cytokines and arterial vasospasm leading to thrombotic events (5).

Irrespective of IVIG therapy, thromboembolic complications, such as portal vein thrombosis, pulmonary embolism, and deep vein thrombosis may occur following splenectomy for hematologic diseases (18, 19). However, in our case, the patient experienced thromboembolic complications immediately following IVIG before splenectomy, which excludes this possibility.

Although a direct underlying mechanism responsible for IVIG-induced thrombotic events needs to be clarified, IVIG should be given with precaution in patients with vascular risk factors such as advanced age, history of cerebrovascular or cardiovascular disease, hypertension, or hypercoagulable and hyperviscosity conditions.

Figures and Tables

References

1. Elkayam O, Paran D, Milo R, Davidovitz Y, Almoznino-Sarafian D, Zeltser D, Yaron M, Caspi D. Acute myocardial infarction associated with high dose intravenous immunoglobulin infusion for autoimmune disorders. A study of four cases. Ann Rheum Dis. 2000. 59:77–80.

2. Emerson GG, Herndon CN, Sreih AG. Thrombotic complications after intravenous immunoglobulin therapy in two patients. Pharmacotherapy. 2002. 22:1638–1641.

3. Lemieux R, Bazin R, Neron S. Therapeutic intravenous immunoglobulins. Mol Immunol. 2005. 42:839–848.

4. Dalakas MC. The use of intravenous immunoglobulin in the treatment of autoimmune neuromuscular diseases: evidence-based indications and safety profile. Pharmacol Ther. 2004. 102:177–193.

5. Hefer D, Jaloudi M. Thromboembolic events as an emerging adverse effect during high-dose intravenous immunoglobulin therapy in elderly patients: a case report and discussion of the relevant literature. Ann Hematol. 2004. 83:661–665.

6. Schiavotto C, Ruggeri M, Rodeghiero F. Adverse reactions after high-dose intravenous immunoglobulin: incidence in 83 patients treated for idiopathic thrombocytopenic purpura (ITP) and review of the literature. Haematologica. 1993. 78:35–40.

7. Brannagan TH 3rd, Nagle KJ, Lange DJ, Rowland LP. Complications of intravenous immune globulin treatment in neurologic disease. Neurology. 1996. 47:674–677.

8. Woodruff RK, Grigg AP, Firkin FC, Smith IL. Fatal thrombotic events during treatment of autoimmune thrombocytopenia with intravenous immunoglobulin in elderly patients. Lancet. 1986. 2:217–218.

9. Kang SY, Kang JH, Kim JS. A case of cerebral infarction following intravenous immunoglobulin therapy in a patient with guillain-barre syndrome. J Korean Neurol Assoc. 2003. 21:217–219.

11. Stasi R, Provan D. Management of immune thrombocytopenic purpura in adults. Mayo Clin Proc. 2004. 79:504–522.

12. Imbach P, Barandun S, d'Apuzzo V, Baumgartner C, Hirt A, Morell A, Rossi E, Schoni M, Vest M, Wagner HP. High-dose intravenous gammaglobulin for idiopathic thrombocytopenic purpura in childhood. Lancet. 1981. 1:1228–1231.

13. Hanna K, Poulin-Costello M, Preston M, Maresky N. Intravenous immune globulin use in Canada. Can J Clin Pharmacol. 2003. 10:11–16.

14. Paran D, Herishanu Y, Elkayam O, Shopin L, Ben-Ami R. Venous and arterial thrombosis following administration of intravenous immunoglobulins. Blood Coagul Fibrinolysis. 2005. 16:313–318.

15. Zaidan R, Al Moallem M, Wani BA, Shameena AR, Al Tahan AR, Daif AK, Al Rajeh S. Thrombosis complicating high dose intravenous immunoglobulin: report of three cases and review of the literature. Eur J Neurol. 2003. 10:367–372.

16. Alexandrescu DT, Dutcher JP, Hughes JT, Kaplan J, Wiernik PH. Strokes after intravenous gamma globulin: thrombotic phenomenon in patients with risk factors or just coincidence? Am J Hematol. 2005. 78:216–220.

17. Dalakas MC. High-dose intravenous immunoglobulin and serum viscosity: risk of precipitating thromboembolic events. Neurology. 1994. 44:223–226.

PDF

PDF ePub

ePub Citation

Citation Print

Print

XML Download

XML Download